fcc_order10_18_20021.. - Applied Antitrust Law

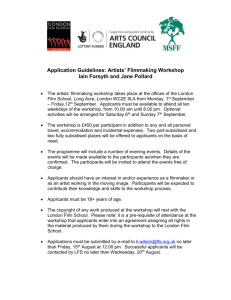

advertisement