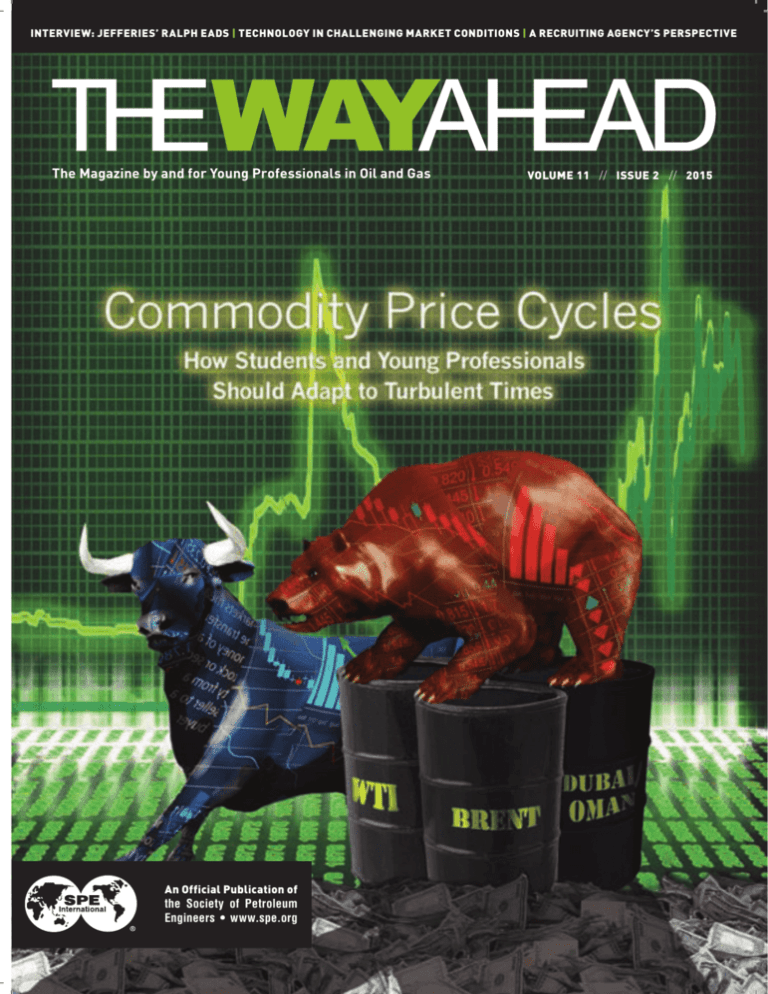

INTERVIEW: JEFFERIES’ RALPH EADS | TECHNOLOGY IN CHALLENGING MARKET CONDITIONS | A RECRUITING AGENCY’S PERSPECTIVE

The Magazine by and for Young Professionals in Oil and Gas

An Official Publication of

the Society of Petroleum

Engineers • www.spe.org

VOLUME 11 // ISSUE 2 // 2015

YOU WON’T JUST TAP OIL RESERVES

YOU’LL TAP YOUR FULL

CAREER POTENTIAL.

At this time, we are recruiting professionals

with the following background and experience:

FACILITIES PROJECT ENGINEERS

FACILITIES ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS

CONTROLS SYSTEMS ENGINEERS

PRODUCTION ENGINEERS

RESERVOIR ENGINEERS

GEOLOGICAL TECHNICIANS

INFO MANAGEMENT & TECHNOLOGY

Are you ready to take your career to the next

Aera encourages a healthy balance between

level? Aera Energy currently has a range of

work and personal pursuits. We’re a diverse

industry-leading opportunities for ambitious

group, though we all have something in common:

professionals. Here, you can make a real impact.

a solid commitment to excellence. If this sounds

We’re big—one of the largest oil companies in

like a culture in which you’d thrive, we look

the USA—yet you’ll always know that you’re an

forward to speaking with you. Find out more

essential part of the team. Based in California,

at workforaera.com

Producing solutions.

Veterans are welcome to apply. Aera is an equal opportunity employer.

Contents

VOLUME 11 // ISSUE 2 // 2015

3

What’s Ahead: A Cautionary Tale

TWA Editor-in-Chief ,Tony Fernandez, on the importance of keeping academic

enrollments high.

4

TWA InterAct: How the Oil Price Drop Affects Students

Presidents of SPE student chapters share their comments on how the new oil price

environment affects petroleum engineering students.

6

TWA Interview: Ralph Eads, Jefferies

Eads, vice chairman and global head of energy investment banking for Jefferies, on

the factors affecting the oil price and the impact on the banking sector.

Cover design: Alex Asfar, SPE.

For the oil price graph, see page 28.

8

Academia: Turbulent Oil Prices, Turmoil for YPs

For young professionals, understanding the governing principles of oil price and

connecting them with facts is key to facing the price turmoil.

10

Americas Office

Office hours: 0730–1700 CST (GMT–5) Monday–Friday

222 Palisades Creek Dr., Richardson, TX 75080-2040 USA

Tel: +1.972.952.9393 Fax: +1.972.952.9435

Email: spedal@spe.org

Asia Pacific Office

Office hours: 0830–1730 (GMT+8) Monday–Friday

Level 35, The Gardens South Tower Mid Valley City,

Lingkaran Syed Putra, 59200 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Tel: +60.3.2182.3000 Fax: +60.3.2182.3030

Email: spekl@spe.org

Canada Office

Office hours: 0830–1630 CST (GMT–6) Monday–Friday

Eau Claire Place II

Suite 900 – 521 3rd Ave SW

Calgary, AB T2P 3T3 Canada

Tel: +1.403.930.5454 Fax: +1.403.930.5470

Email: specal@spe.org

Europe, Russia, Caspian, and Sub-Saharan Africa Office

Office hours: 0900–1700 (GMT+1 ) Monday–Friday

First Floor, Threeways House, 40/44 Clipstone Street

London W1W 5DW UK

Tel: +44.20.7299.3300 Fax: +44.20.7299.3309

Email: spelon@spe.org

Houston Office

Office hours: 0830–1700 CST (GMT–5) Monday–Friday

10777 Westheimer Rd., Suite 1075, Houston, TX 77042-3455 USA

Tel: +1.713.779.9595 Fax: +1.713.779.4216

Email: spehou@spe.org

Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia Office

Office hours: 0800 to 1700 (GMT+4) Sunday–Thursday

Fortune Towers, 31st Floor, Offices 3101/2, JLT Area

P.O. Box 215959, Dubai, UAE

Tel: +971.4.457.5800 Fax: +971.4.457.3164

Email: spedub@spe.org

Moscow Office

Office hours: 0900–1700 (GMT+4) Monday–Friday

Perynovsky Per., 3 Bld. 2

Moscow, Russia, 127055

Tel: +7 495 937 42 09

Email: spemos@spe.org

Pillars of the Industry: Upping the Ante on Technology, Leadership

John Wishart, Lloyd’s Register, and Judith Dwarkin, ITG Investment Research,

emphasize technology and leadership growth as a strategy to face challenging

market conditions.

13

Economist’s Corner: Price Cycles Explained by an Expert

Gürcan Gülen of University of Texas at Austin explains the mechanics of oil

price cycles.

16

HR Discussion: Recruiting in Current Market

In a challenging market condition, an astute observation of the investment flow in the

industry can help young professionals land in good jobs.

18

Forum: The Sky is Falling—Again

Euan Mearns of Energy Matters blog, Jared Wynveen of McDaniel & Associates

Consultant, and James Fann of Cenovus energy share their perspectives on the oil

price downturn.

21

SPE 101: SPE Technical Disciplines

Understanding SPE’s technical disciplines can help you get the most out of your

membership.

22

Discover a Career: Reserves Estimation

Larry Mizzau, principal of reserves and resources governance at Cenovus Energy,

explains what a career in reserves estimation entails.

25

Technical Leaders: Ward Polzin, Centennial Resource Development

Polzin’s comments on the effect of commodity prices on the engineer and the industry.

28

Soft Skills: How to Survive Oil Price Volatility

Young professionals can use downturns as an opportunity for long-term career growth.

30

Tech 101: Keystone XL—Rhetoric vs. Economics

Craig Pirrong of Bauer College of Business discusses the economics of Keystone.

33

YP’s Guide To… Russia and China

How oil prices affect the economies of countries differently.

35

YP Newsflash: 2014 SPE YMOSA Winners

Networking, volunteering—common thread of award winners’ messages.

An Official Publication of

the Society of Petroleum Engineers • www.spe.org

Printed in UK. Copyright 2015, Society of Petroleum Engineers.

TWA EDITORIAL

COMMITTEE

TWA STAFF

ADVERTISING SALES

Glenda Smith, Publisher

AMERICAS

John Donnelly, Director, Magazines and

Web Content

10777 Westheimer Rd., Suite 1075

Houston, Texas 77042-3455

Main Tel: +1.713.779.9595 Fax: +1.713.779.4220

Pam Boschee, Senior Manager

Magazines

Craig W. Moritz

Assistant Director Americas Sales & Exhibits

Tel: +1.713.457.6888 cmoritz@spe.org

David Vaucher, Alvarez & Marsal

Anjana Sankara Narayanan, Editorial

Manager

Evan Carthey

(Companies A–L), Sales Manager Advertising

Tel: +1.713.457.6828 ecarthey@spe.org

LEAD EDITORS

Alex Asfar, Senior Manager Publishing

Services

EDITOR-I N- CH IE F

Tony Fernandez, Jefferies LLC

DE PUTY EDITOR-I N- CH IE F

Jarrett Dragani, Cenovus Energy

T WA ADV ISE R

Amber Sturrock, Chevron

Anisha Mule, University of Tulsa

Angela Dang, Colorado School of Mines

Craig Frenette, Cenovus Energy

David Sturgess, Woodside Energy

Harshad Dixit, Halliburton

Islin Munisteri, State of Alaska

Ivo Foianini, Halliburton

Jenny Cronlund, BP

Kristin Weyand, ConocoPhillips

Madhavi Jadhav, Shell

Maxim Kotenev, Sasol

Paulo Pires, Petrobras

Rita Okoroafor, Schlumberger

Rob Jackson, Mountaineer Keystone

Mary Jane Touchstone, Print Publishing

Manager

Mark Hoekstra, Sales Manager–Canada

Tel: +1.403.930.5471 Fax: +1.403.930.5470

mhoekstra@spe.org

EUROPE, RUSSIA, AND AFRICA

Rob Tomblin, Advertising Sales Manager

Tel: +44.20.7299.3300 Fax: +44.20.7299.3309

rtomblin@spe.org

Laurie Sailsbury, Composition

Specialist Supervisor

MIDDLE EAST, SOUTH ASIA, AND ASIA PACIFIC

Allan Jones, Graphic Designer

Clive Thomas, Advertising Sales Executive

Tel: +971 (0) 4.457.5855

cthomas@spe.org

Ngeng Choo Segalla, Copy Editor

Available Online and

Apple App Store/GooglePlay

Shruti Jahagirdar, Shell Technology India

EDITORS and ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Alex Hali, Baker Hughes

Aman Gill, Nexen ULC

Asif Zafar, Halliburton

Batool Haider, Stanford University

Carter Clemens, BP

Chieke Offurum, EOG Resources

Colter Morgan, Chevron

Dane Gregoris, ITG

Dilyara Iskakova, Hess Corp.

Islam Ibrahim, GUPCO

Jakob Roth, Independent

James Lloyd, Mayer Brown LLP

Li Zhang, Devon Energy

Matthew French, ConocoPhillips

Michael Stratton, Accenture

Muhammad Taha, Mari Petroleum

Nazneen Ahmed, Independent

Oyebisi Oladeji, Schlumberger

Reva Cipto, Dialog

Rodrigo Terrazas, Total

Samuel Ighalo, Halliburton

Sara Davila, MHWirth

Shubham Sharma, Indian School of Mines

Dhanbad

Tiago de Almeida, Universitário de Barra

Mansa

Thomas Shattuck, Wood Mackenzie

Thresia Nurhayati, Halliburton

CANADA

Craig Moritz, Assistant Director

Americas Sales & Exhibits

Stacey Maloney, Print Publishing

Specialist

Dana Griffin

(Companies M–Z), Advertising Sales

Tel: +1.713.457.6857 dgriffin@spe.org

Read current and past issues, today!

Search “The Way Ahead”

www.spe.org/twa

ADDRESS CHANGE: Contact Customer Service at 1.972.952.9393 to notify of address change or make changes online

at www.spe.org.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: The Way Ahead is sent as a member benefit to all SPE professional members who are age 36 or under.

Subscriptions are USD 15 per year for other SPE members, and USD 45 per year for nonmembers.

TWA THE WAY AHEAD (ISSN 2224-4522) is published three times a year (February, June, October) by the Society of

Petroleum Engineers, 222 Palisades Creek Drive, Richardson, TX 75080 USA.

SPE PUBLICATIONS: SPE is not responsible for any statement made or opinions expressed in its publications.

EDITORIAL POLICY: SPE encourages open and objective discussion of technical and professional subjects pertinent to the

interests of the Society in its publications. Society publications shall contain no judgmental remarks or opinions as to the technical competence, personal character, or motivations of any individual, company, or group. Any material which, in the publisher’s

opinion, does not meet the standards for objectivity, pertinence, and professional tone will be returned to the contributor with

a request for revision before publication. SPE accepts advertising (print and electronic) for goods and services that, in the publisher’s judgment, address the technical or professional interests of its readers. SPE reserves the right to refuse to publish any

advertising it considers to be unacceptable.

COPYRIGHT AND USE: SPE grants permission to make up to five copies of any article in this journal for personal use. This permission is in addition to copying rights granted by law as fair use or library use. For copying beyond that or the above permission:

(1) libraries and other users dealing with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) must pay a base fee of USD 5 per article plus

USD 0.50 per page to CCC, 29 Congress St., Salem, Mass. 01970, USA (ISSN0149-2136) or (2) other wise, contact SPE Librarian at

SPE Americas Office in Richardson, Texas, USA, or e-mail service@spe.org to obtain permission to make more than five copies

or for any other special use of copyrighted material in this journal. The above permission notwithstanding, SPE does not waive its

right as copyright holder under the US Copyright Act.

Canada Publications Agreement #40612608.

What’s Ahead–From TWA’s Editor-in-Chief

Déjà vu for Petroleum Engineers:

A Cautionary Tale

Tony Fernandez, Editor-in-Chief, The Way A head

I

14,000

12,000

Number of Students

remember my first year in the industry very fondly:

it was 2006, oil prices had been climbing steadily for

over half a decade, and the “big crew change” was

starting to become dinner table discussion. The brain

drain that would eventually come from the retirement of senior

employees was imminent, experts advised, and it seemed like

companies were taking advantage of the good times to hire

like crazy as they positioned themselves to hedge the effect on

their operations.

I vividly remember a recruitment event organized by a

large independent during the ATCE for which they rented

the entire Sea World theme park in San Antonio and threw a

party for us. It was an extraordinarily memorable event for any

impressionable recent grad, and the future seemed prosperous.

The Petroleum Economist encapsulated the hiring spree by

quoting the head of US recruiting for one of the supermajors as

saying, “Times are very good for us…and we are expanding–

USD 60 [a barrel] oil will do a lot for your business. At the same

time…a large number of employees are in their 50s and we

need to increase our hiring across the board.”

Academia listened to industry’s pleas for help, experiencing

a meteoric rise in petroleum engineering enrollment not seen

since the 1980s (Fig 1). Unfortunately, those students in the

1980s largely found themselves unemployed upon graduation

as a result of cost-cutting measures following the oil price

collapse of 1987, the result of which became the very same “lost

generation” of talent that evidently now needs to be bridged by

the big crew change.

Fast-forward to today and, after some wild swings in

commodity prices, to be sure, we nonetheless see oil once

again hovering at around the same USD 60 mark which I fondly

recall from the birth of my career. But a quick study of the

headlines paints a starkly different picture this time around, as

seemingly every company is either laying off people, freezing

hiring, or doing both. An onslaught of such headlines has

turned the mood in university campuses to an anxious and

somber (if not pessimistic) one, which is completely opposite

to the confident euphoria when I was there. I encourage you

to read the TWAInterAct section, which features comments

from SPE student chapter presidents on how the price drop is

affecting students.

According to a Schlumberger Business Consulting study

reported in the Houston Chronicle, our industry was expected to

have a net loss of professionals by 2014-2015 due to retirements,

and that was before today’s commodity-driven hiring freezes

and early retirement packages. This means that as the big crew

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

0

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Academic Year

Fig. 1—US petroleum engineering enrollment. Courtesy

of Lloyd Heinze, Bob L. Herd Department of Petroleum

Engineering, Texas Tech University.

change is finally under way—and the industry prepares to feel

the effects of its neglect on its workforce during the 1980s and

1990s—academia is beginning to experience the same cold

shoulder from the industry in the form of underfunding and low

hiring that it felt back then.

It is a tough but understandable decision for executives: do

you stay the course and allow your company to hemorrhage

right into bankruptcy, or do you cut costs any way you can (even

if it means laying off people) to try to secure the future of the

business? Your employees (those still around, anyway) and

shareholders would certainly support the latter.

Final Thoughts

At a time when the wound is still healing from the damage of

the 1980s, we as an industry must ask ourselves whether ripping

the scab off by virtue of another lost generation will in fact leave

a permanent scar and cement our reputation as an industry of

boom/bust hiring—incapable of protecting the lifeblood of the

business by adequately managing knowledge transfer between

generations. The irreparable effects such a reputation could

have on the industry’s pipeline of talent are self-evident and too

grave to want to think about. Students will always be pragmatic

about their careers and, facing an uncertain future, they will

seek alternatives and, more than likely, never return.

Indeed, the similarities between the 1980s and today are

too many and ominous to ignore. Does the cyclical nature of

our business automatically doom us to these lost generations

during each abrupt dip in commodity prices? Or will there be

a generation that finally says, “fool me once, shame on you; fool

me twice…”? TWA

Vol. 11 // No. 2 // 2015

3

TWA InterAct

Want More Internships, More Hiring—Oil

and Gas Students Tell Companies

The rapid decline in commodity prices has caused most oil and gas companies to reassess their hiring goals or cut back on staff.

What does someone about to enter our industry make of this shift in hiring trends? From internships and full-time job offers to

pivotal academic decisions, students looking to enter the oil and gas industry are very sensitive to price fluctuations. We asked SPE

student chapter presidents from around the world how the new oil price environment has affected the status quo at their universities.

The downturn is probably the best thing to happen to our young

While our students understand that regardless of what oil prices are,

SPE chapter. We have grown in membership and involvement

there will always be a demand for EITs, students, and interns. We are

in our organization because students are understanding that a

especially nervous with news of companies rescinding student and

degree alone cannot guarantee employment.

new grad offers, but so far those that are interested in energy remain

William Eerdmans

interested and will pursue opportunities that are available.

University of North Dakota, USA

Kevin Zhou

McGill University, Canada

The biggest hit has come to our upperclassmen students as some have not had field internship

opportunities and are about to enter their last year of college. According to our Capstone

Design Instructor, over half of the domestic students in the BS program have not found fulltime employment for post-graduation. Morale is low among our students especially when

asked to answer the questions, “What will you do after graduation?” or “Where will you be

working this summer? However, those dedicated to the industry are pushing forward and

fi nding ways to boost their résumé and technical understanding.

Tyler Carter

University of Tulsa, USA

There have been instances where internships have been shortened, and we hear

rumors of some internships being taken off the table altogether. We are becoming

more involved with the SPE Gulf Coast Section and are sending seniors without jobs

to their events for the opportunity to network and learn new skills.

Aziz Rajan,

University of Houston, USA

Companies in Colombia have adopted severe austerity policies, including cuts in

internships. Ongoing recruitment processes were suddenly canceled and many of our

young professionals were fi red in mass, highly increasing the unemployment index in our

Facing the fact that just one of our more than

demographic. This is generating a deep shift through academia and recent graduates with

20 students will get a job offer or internship

regard to increased experience requirements and lack of job opportunities. Consequently,

has encouraged students to develop more

the number of graduate students is going up.

professional competencies. Many of us will focus

Henry Mauricio Galvis

Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia

our attention in research.

Alfredo de la Fuente

Universidad Nacional de Ingenieria, Peru

4

In our last career fair, we had more construction and

The new oil price has influenced our student population in Russia strongly.

automobile companies than oil and gas companies as

Most Russian oil companies have limited places for graduates and, as a result,

the latter are not recruiting at the moment. So students

we have seen lowered activity at our career fairs from the industry. Some of

are resorting to working in related fields like chemical

my young colleagues have been laid off because of job cuts.

Alexey Suvorov

plants, automobiles, and consulting fi rms.

Novosibirsk State University, Russia

Ezeike Kenechi

University of Salford, UK

We can feel the tentativeness and exertion which is present on the

We went from a 40% direct-hire rate in the last 5 years to zero job

petroleum market during chats with other students, professors,

offers this year. Budget cuts have affected everything from student-

and lecturers. However, dedicated and passionate students

worker jobs to chapter funding and even our graduation venue. The

continue to get internships, part-time jobs, and even full-time

harsh reality is that, for the near future, prospects are dismal with

employments at prestigious companies.

hiring freezes throughout the workforce. Non-Qatari residents (80%

Joschka Röth

RWTH Aachen University, Germany

of our student population) have the added complexities that come

with the phenomenon of “Qatarization,” leaving almost no room for

employment or research opportunities.

Ahmed Rauf

Texas A&M University at Qatar, Qatar

As part of our degree, we have to undergo a 6-month internship

before graduation. Unfortunately, that is where we have felt the

biggest impact. Virtually every company has an office or lab in

Pau, but only two companies have hired interns this year. Out of

the 50 students in our program, only approximately 60% secured

The second phase of the crash, from November to January, had the

an internship, 33% of which came in the form of lab assistants to

biggest impact on us, especially those who are about to graduate.

our professors.

While some companies continued to provide internship opportunities

Casaurang Christophe

Université de Pau, France

despite the downturn, a lot of companies originally registered for

campus recruitment backed off. Most of the students are in a dilemma

whether to pursue higher studies or switch career paths to sectors

like business analytics. To that end, a few are set to join tech startup

companies and consulting fi rms.

Vikram Sai

Indian School of Mines, India

Oversaturation of petroleum engineering students seems to be a problem:

our institute had 40 undergrads in 2004, compared to the 90+ undergrads

today. Several seniors in our program with high grades are unable to fi nd

jobs in this environment, and a few of our fi rst-year students witnessing

their difficulties have left the degree, presumably as a result of the lack

of prospects.

Imran Hullio

Mehran University, Jamshoro, Pakistan

More than 50% of our senior students, who are supposed to be

on internship, have yet to secure one. This has raised anxiety

on campus as most students are considering furthering their

education by enrolling in a master’s degree program rather than

starting their career in oil and gas. Some students intend to further

Companies are cutting off their sponsorships, donations, and even the

their education in related fields pending a price recovery, while

day-to-day visits to the industry engagement opportunities we provide to

others intend to branch into other areas outside the oil and gas

our students. It has become so hard to provide internships and different

industry altogether.

technical development programs. Our graduates are now suffering truly as

Jackto Oghenefejiro

Madonna University, Nigeria

the opportunities all over the world have gone limited.

Ahmed Elgamal

Suez University, Egypt

Vol. 11 // No. 2 // 2015

5

TWA Interview

Ralph Eads III

Vice Chairman, Global Head of Energy

Investment Banking, Jefferies LLC

Ralph Eads is

vice chairman

of Jefferies LLC

and global head

of Jefferies’

Energy Investment

Banking Group. His

extensive mergers and acquisitions

(M&A) experience includes working on

more than USD 300 billion in energy

M&A transactions. Before this, Eads

was president of Randall & Dewey,

which was acquired by Jefferies in

2005. His previous positions were

executive vice president of El Paso

Corp., handling its unregulated

businesses; head of the energy group

of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette; and

senior positions at S.G. Warburg and

Lehman Brothers. Eads serves on the

board of trustees of Duke University.

associated with finance, but you also get

exposed to the innovation in the industry.

What or who inspired you to work in

the oil and gas industry?

How has Jefferies’ business

changed? What fundamental

changes are Jefferies making to

adapt to this new price regime? What

makes Jefferies different from other

M&A banks?

I am a fifth generation Texan and a native

Houstonian, so I have been around the

oil business my entire life. One of the

things that drew me to the industry is all

the great lore around it. I have always

liked all the stories and the traditions of

risk-taking and boom and bust. It is just a

fascinating industry.

You have assumed various financial

roles throughout your career in the

industry. What roles do you or did

you enjoy most and why?

I enjoy my current job the most. Here

at Jefferies, we have a true combination

of finance and technical expertise. It is

stimulating to see interesting projects

and to do technical analysis on individual

plays. You get the transactional activity

6

How do fluctuating oil prices,

specifically the low oil prices seen

today, affect the mergers and

acquisitions (M&A) business?

It kills it; the market just stops. We mainly

act for sellers and that business has

stopped because buyers want to buy

packages at USD 50/bbl oil, and sellers

do not want to sell that low given that the

price of oil was USD 80/bbl only a short

time ago. If prices stay low, sellers will

start selling at the lower price, or if prices

recover, we will get back to a market that

transacts around USD 80/bbl oil. But for

now, the market is frozen.

We are reacting to the market. In truth,

we will be less busy in this environment

than we would be in a “normal” price

environment. But companies still need

capital and when you do a private

transaction, the buyer of that security

wants to understand the asset they

are buying, what it looks like, and the

development plan that goes with it.

Fortunately, there is a lot of private capital

available for the industry right now, and

we are a leader in private capital-raising

because of our technical expertise.

We have 40 engineers, geologists,

and geophysicists embedded in our

firm. We do not just package the data to

sell; we actually think about the technical

issues and say “what opportunities are

there with this asset to make it more

valuable, and how do we portray that to

the market?” For example, we have done

a complete basin analysis of the Eagle

Ford Shale. One of the reasons we do

this is that it allows us to understand what

is happening in the different plays. We

are oilmen first, financiers second. We

are driven by what is happening to the

underlying business of the industry.

Are many startups failing during this

period of low-cost oil?

It depends. Some startups have strategies

that can live in a USD 50/bbl world,

and some do not. For example, if it is a

company that is interested in tertiary

recovery—high-cost oil—then those

business plans will idle. Maybe they

will not go out of business, but they will

not spend any capital because they

are not attracting any. There are some

businesses that can adapt to a lower

price environment and still make money

because of the underlying investments

that they are trying to create.

What are some of the social

and political causes of the low

commodity prices?

We have the perfect storm for low prices

right now: the Saudis have the will and

the money to cut prices, there is political

stability in all the bad actor countries,

and we have slack global demand. Those

are the three variables that contribute

fantastically to low oil price. Though,

any one of these three variables could

change quickly.

I think first, and most importantly, the

Saudis want to inflict pain on Iran and the

other bad actors, Syria, Iraq, etc. So they

are trying to increase their political clout

and to hit other countries’ pocketbooks.

Secondly, they want to create uncertainty

about the long-term oil price because

they want the global companies to use

USD 50/bbl for planning prices rather

than USD 70/bbl, to cut projects and lower

their production. They are just trying to

drive down price and it does not take

very much oil to do that.

What will it take for the oil price to

increase? Do you think oil price will

ever return to USD 100+/bbl?

Sure, absolutely, and maybe even in the

next 6 months. When prices fell during

2008–2009, which was driven by demand

fall, there was a 3 million BOPD overhang

and prices recovered in 6 months. What

everyone misses here is the amount of

“extra” oil we have today, let us say, 1

million BOPD. That is nothing in a 90

million BOPD market. In the 1980s, it was

a 10 million barrel surplus in a 70 million

BOPD market. The current deliverability

margin is quite low and the world

depletes at around 7 million BOPD in a

year. There is not that much extra oil to

go around and so the market is going to

tighten pretty quickly.

Once the Saudis make their point,

they will turn the valve cutting off

500,000 BOPD and the low price will

solve itself in 3 months. Outside of the

market normalizing, the marginal cost

curve for the industry continues to march

up. We have found all the cheap oil and

we are going to real frontier regions such

as really deep water to get incremental

oil; it is expensive. There is not much

cheap oil lying around. This low oil price

is such a weird aberration because

actually the underlying economics

are that the industry’s cost structure

continues to march up. The world needs

USD 80/bbl of oil to work.

Absent change in production from the

Saudis, prices will probably stay down

for a while and the industry will correct.

I do not think on a global basis the

industry can make money at USD 50/bbl,

so natural depletion together with lack

of investment will cause prices to turn

around. If prices stay low, people will

start to take drastic actions and the longer

prices stay down, the higher they will

rebound later.

What are the roles of demand and

supply in the oil and gas market?

What sort of projection can you make

for the future global energy demand?

Demand is not decreasing, it is just

not growing. First, China is becoming

more efficient, which is natural in any

developed economy. Second, demand

in the emerging markets, where they are

not as efficient, has gotten smoked by the

[strengthening] dollar. Everyone buys oil

in dollars and the dollar has appreciated

against other currencies in the last 6

months—by a lot. A lot of the downward

pressure on prices has been offset by

the fact that the dollar has become a

lot stronger.

On the supply side, we have enough

oil and natural gas to run the planet for

at least the next century. We may not

choose to, but the resources exist. We

won’t run out of energy, and energy

efficiency is going to reduce energy

demand over time. In fact, it has already

reduced demand in that energy intensity

per dollar of output is going down fairly

rapidly. As this continues, the global

economy gets less energy intensive.

How do different countries affect the

demand and supply of oil and gas in

the global market?

The list of countries that will contribute

to incremental deliverability is tough. It

is Iraq, Iran, Libya, and maybe Russia.

Although these countries are stable right

now, people are not rushing to invest

there, because history says they are not

going to stay that way.

The lease sales in Mexico will add

to supply, but in the much longer term.

The challenge with onshore Mexico is

going to be infrastructure—they do not

have roads and pipelines, and the recent

oil price changes are going to delay a

lot of Mexico’s production too. Then you

have the US, which is stable and will

continue to increase production even at

today’s prices. The key to growing US

production is the Permian Basin. It has

become the marginal supplier of oil in

the world and the industry’s center of

gravity. I estimate the Permian Basin has

recoverable reserves of 250 billion bbl of

oil. That is a lot of oil and there is a lot of

capital needed to get it.

What should be the response of

policymakers to oil prices in

countries around the world?

So far, no government leader has stood

up and said anything about anything

other than Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Kuwait

all saying “we are not cutting production

any time soon.” At some point, they will

say they have reached the benefit that

they were after, but what is that trigger?

Who knows.

The US has exponentially increased

oil production with the shale

revolution. How sustainable is this

level of oil production?

The resource plays in the US are in the

third inning of the game, and they will

continue to produce for a long time. In

the 1950s, the San Juan basin recovery

factors were estimated at 20% to 30%.

Now, there are places in the basin where

recovery has been 110% gas in place due

to technological advances that increased

recovery efficiency and unlocked

neighboring horizons. That same trend is

going to happen in other plays. Right now,

the recovery factor in the Wolfcamp is

10%; what has to happen technologically

to get to 50%?

The US has been granted a huge

gift in the shale boom. It has reduced

the cost of energy and it has created

lots of employment in a world where

we are worried about stagnation in

wages and a lack of good jobs. The

energy industry has been a shining

beacon for the US, and it is important to

remember that.

Continued on page 15

Vol. 11 // No. 2 // 2015

7

Academia

Turbulent Commodity Prices and the

Turmoil for Young Professionals

Tom Seng, University of Tulsa

From June 2014 to January 2015, global

crude oil prices dropped by almost

60%, from about USD 108/bbl to USD

46/bbl. There were many factors that

drove these prices downward. Being

an integral part of the industry, it is

important that young professionals

understand the governing principles

and be able to connect them with facts.

The following are some of the

prominent factors responsible for the

drastic change in oil prices.

Supply and Demand. According

to the December 2014 monthly

update of the United States Energy

Information Administration, the global

supply of liquid fuels increased by

1.8 million B/D to 92 million B/D in

2014 while demand did not keep pace.

Domestic oil production in the US

increased to 8.8 million B/D last year,

the highest level in 30 years, and US

crude oil inventory levels have reached

an 80-year high. Meanwhile, US

demand for oil declined from what had

been a 10-year high.

Economic. Strong economic growth

translates into higher energy usage

and can impact prices positively. But

the converse is also true, in that weak

economic indicators could represent

lower energy consumption and,

consequently, lower prices. The US,

China, Japan, and India are the world’s

top consumers of crude oil.

Europe consumes 22% of the

world’s oil. Meanwhile, Europe’s

largest producer of crude, the United

Kingdom, became a net importer in

2013. Economic indicators for all these

countries are intensely watched daily

as traders attempt to determine the

future direction of the price of oil and

countries become intrinsically tied to a

global economy—one that can be very

fickle in nature.

Political. Energy will always be a

controversial issue pitting producers

against consumers and environmental

groups. A recent example of this is

the Keystone XL oil pipeline project

in North America. The planned route

from Canada’s Alberta province to

Cushing, Oklahoma, has run into issues

regarding a required international

border permit, landowner rights,

and environmental concerns over

the process that produces the crude

oil itself.

Tom Seng is an assistant professor of energy business at the

University of Tulsa working with course development and

specializing in energy risk management, asset optimization,

and energy commodity trading. He is also a consultant and

teaches an online course on fi nancial energy commodity

trading that he developed for Pennsylvania State University.

Before joining the academia, he worked for more than 30

years in the natural gas industry in roles such as director of

risk control and manager of product marketing for several energy companies. He

holds a BS in political science and history and an MBA in international oil and gas

management from the Robert Gordon University.

8

Geopolitical. There are probably

far too many global events that can

be perceived as having an impact on

oil prices. Internal and cross-border

confl icts in oil-producing countries and

regions tend to cause fears of supply

disruption in world energy markets.

Civil unrest in Nigeria and the South

Sudan, the ongoing dispute between

Israel and Hamas over Palestine,

Iran’s nuclear status, Russia’s stance

on Ukraine, Somali pirating of crude

oil tankers in the Gulf of Aden, and the

ISIS takeover of producing fields and

other oil-related infrastructure in parts

of Iraq are just some of the continuing

events being monitored by energy

markets. Not to mention that the actions

of the Organization of the Petroleum

Exporting Countries alone can cause

earth-shattering shakeups in global

oil markets.

Cross-Commodity Relationships.

Supply and demand fluctuations in the

many refi ned and distilled products

derived from oil directly impact

crude prices. Gasoline, diesel, jet

fuel, and heating oil are among the

major oil products that affect the price

of crude.

Human Factor. Crude oil is traded

globally in fi nancial markets. These

are transactions for the future

purchase or sale of oil and most occur

electronically. As such, traders look for

any information that could influence

price direction. For them, it is all about

perception. They are human beings

and they tend to react emotionally as

we all do. Billions of dollars are at stake

and so both greed and fear drive the

market. As such, irrational decisions

can be made without consideration for

important facts that may be uncovered

later. This is why some oil price

movements may not make sense to

the average observer. Add to this the

more recent use of supercomputers,

which use complex mathematical

algorithms and execute large volumes

of calculations in nanoseconds and you

have an extremely volatile marketplace

for energy commodities. When oil

prices rise, producers, far too often,

believe they will continue to rise and so

don’t sell when they should.

How Oil Prices Influence

Academic Enrollment

So, what does the current oil market

environment mean for academic

institutions and their students?

Unfortunately, the job market in

the oil and gas industry will become

tighter. But the industry has seen these

cycles before. As recently as 2008, oil

prices plummeted to about USD 32/bbl

in December of that year after reaching

a high of USD 145/bbl in July. In the

early 1980s, a tremendous “bust” in oil

prices had far-reaching consequences

for the oil and gas business. Some of

those who lost their jobs at that time

never returned to the industry.

Two potential scenarios arise out of

these situations. Firstly, as companies

seek to cut costs, they may choose to

scale back on tuition assistance for their

employees, making it harder for them

to continue to attend college, or for new

students to enroll.

Secondly, and the more likely

scenario, is that at times like these,

people seek to diversify their

knowledge and look for a form of

retraining. Enrollment in graduate

programs, in particular, tend to

increase as people desire that

“next level” degree that separates

them from their peers. Others may

wish to advance from their current

positions and eventually move into a

management role.

Many people who already possess

a technical degree may wish to

learn more about the business and

leadership aspects of the industry

as well. Merely being enrolled in an

advanced program can be a positive

signal to a current or future employer

that the candidate is constantly striving

to learn new skills that can add value to

the company.

The Effect on Job Market

For soon-to-be graduating students,

there should still be ample

opportunities for employment in the

oil and gas industry. Every time we

experience a bust, such as the current

one, companies take steps to reduce

costs. And yes, some companies will

put a freeze on hiring.

But what tends to happen is that

companies will look for ways to reduce

the current workforce, rather than stop

recruitment altogether. This works

to boost confidence in academic

institutions and job seekers about the

company’s position and ability to ride

through tough times.

One way in which they can do this is

by offering early retirement packages

to their more senior employees.

Another step is pruning the middle

management by virtue of output

optimization, so youngsters are always

encouraged to step up their game and

acquire skills fast.

Finally, there has been an age and

experience gap in the oil and gas

industry for quite some time now. Some

of the previous price busts resulted in

a brain drain because of experienced

people finding employment in other

industries. This has created the need to

find good replacements and get them

up to speed rather quickly. We are yet

to fill this gap.

A key factor that can help in gaining

employment is to differentiate oneself

from others in the job market. A more

diverse academic background and a

cursory understanding of the business

can go a long way in impressing a

potential employer both on paper and

in an interview setting. Being articulate

in the terminology of the industry

illustrates some basic understanding of

what the job may entail as well.

Swaying With Commodity

Prices Can Hurt Companies

There is a future market for crude oil,

which provides an opportunity for

producers to lock in a price down the

road. With the recent fall in oil prices,

it has become apparent that many

companies failed to take advantage of

this risk-reducing mechanism. They

can now see the consequences of their

inaction in the form of lower revenue

and stock prices.

On the other hand, those

companies with the foresight to

take what the market gave them in

terms of high prices last year will

reap the benefits of their prudent

decision making.

In my opinion, corporate

executives have an obligation to

their stakeholders. While this group

encompasses the shareholders,

stakeholders comprise several groups

that are, or may be, impacted by

the company’s success or failure.

Employees, customers, suppliers, and

the general business environment

are all affected by the rise and fall of

corporate earnings.

As such, it is key for companies to

adopt a long-term approach that can

guarantee an even-keeled revenue

stream and business sustainability. This

is to the benefit of all stakeholders and

to the hope of the new generation that is

on the brink of shaping the pathway to

the future.

At the same time, young

professionals need to do their part,

too. Being swayed by the market’s

rapidly changing numbers is not

going to be helpful. Understand

that you belong to a long-standing

industry with immense power to

drive the world. Other industries are

growing too, and with collaboration

and innovation, we can bring about

improvements and advancements to get

the economics of our commodities back

on track. TWA

Vol. 11 // No. 2 // 2015

9

Pillars of the Industry

Upping the Ante on Technology and

Leadership in Challenging Market Conditions

Part 1: John Wishart, Lloyd’s Register

Science and engineering is the

lifeblood of my career and a passion

since sixth form. It was my teacher

who first encouraged me to enroll

in engineering, which later led

me to qualify with a degree in

chemical engineering.

My first job was with John Brown

E&C in London where I worked on

projects in the oil and gas industry.

After a few years, my job with BP took

me from the engineering contracting

sector to a role focused on project and

facilities engineering. My next career

step was joining the then newly founded

Genesis Oil & Gas, moving to Aberdeen

and then to Houston, by which time

the company was owned by Technip

and later I became Technip’s US chief

executive officer.

While it is true that the mistakes

you make along the way help you learn

and progress in life, I can say that I

have truly gained a lot personally and

professionally from the journey I have

made and the people I have worked

with. When you start out in the world

of work, knowing how to take your

educational knowledge to the market

place and learning how to apply it in

different ways in different situations is

critical to your success in life.

I believe that harnessing and sharing

expertise and talent, which exists within

any business, is a fundamental way

that every person can use to enhance

the service and support a company

provides its clients.

At Lloyd’s Register Energy, I am

proud of our employees because thanks

to their team work and efforts, our

business won the 2014 British Quality

Foundation award for our Global Energy

Transformation program, which has

driven positive change inside and

outside of our business.

Challenges for the Industry

Oil prices are one of the most pressing

challenges of our industry today. The

industry is precariously balanced

between long-term success and failure,

and the choices that we make in the next

few years will determine whether it has

a future or not. Technical innovation can

no longer be an afterthought for business

or government; it must be central to any

organization’s strategy for sustainable

growth and market leadership.

My appointment as chairman of

the Industry Technology Facilitator

(ITF) group could not have come at a

more interesting time for technology

development and I look forward to

John Wishart leads the energy business of Lloyd’s Register.

Before joining Lloyd’s Register in 2011, Wishart was the

president of GL Noble Denton. He began his career in

technical, project, and leadership roles in the upstream and

downstream sectors, first with John Brown and then with BP.

He later joined Genesis Oil & Gas Consultants, which was

later bought by Technip, and Wishart became the president

and chief executive officer for Technip. In 2014, he was

appointed as the chairman of the Industry Technology Facilitator, a not-for-profit

organization, driving technology development and collaboration within the oil and

gas industry.

10

ensuring that ITF continues to play a

fundamental role in helping to advance

the implementation of new technologies

in the energy industry.

Even in an industry as regulated

as offshore oil and gas exploration,

there is always room for improvement.

Identifying these opportunities is best

accomplished by adopting a holistic,

rather than prescriptive, set of safety

regulations that focus on technology

as well as training, taking into account

the roles that equipment, systems,

processes, and people play in building

and maintaining a safety culture.

Recently, we have seen the debate

gather momentum on how the industry

needs to improve enhanced oil recovery,

with aspirations of moving from 40%

to 70% on recoverable reserves. Our

global research (the Lloyds Register

Energy Technology Radar survey) has

helped to draw out these key issues and

trends from personnel in the oil and gas

industry:

1. Innovation is drawing on a range of

technologies rather than any single

breakthrough.

2. A variety of technologies that

look set to have a high impact

in the coming years are related

to extending the life of existing

assets—enhanced oil and gas

recovery.

3. The near-term effect of automation

on remote and subsea operations

is identified as firms seek to cope

with challenging environments.

4. High-pressure/high-temperature

drilling and multistage fracturing

are also expected to have a major

impact, but are expected to be

fully deployed from 2020.

Going forward, technology will be

an enabler. If you look at the business

challenges we face today—the issues

around safety, environment, and costs—

you realize that the industry needs

to embrace technology even more.

Collectively, we need to look harder

at technology to help solve many of

those issues.

The Effect of Oil Price Drop. The

current price environment is very much

like a severe stress test to determine

which companies have their finance and

operations in order. Those that spent

too much to lease equipment and plant

to drill or have high operating costs are

most likely to suffer. If prices drop lower

and stay there into next year, providers

of drilling services and oilfield gear will

need to cut prices to retain customers—

moves that will help preserve oil

company margins; operators will

demand higher levels of integrity from

their contractors on equipment, systems,

and personnel.

Crew competence and specific

training to reduce downtime and the

heavy costs associated with equipment

failure will be of critical importance

to tomorrow’s winners. Manufacturers

will have to review their equipment

designs for functionality and failure

and make adjustments based on

new requirements.

One of the difficult questions

to address is how to find the best

strategy to remain relevant and hedge

any job-loss risk during downturns.

One of the key factors is competition.

Oil and gas companies affected by the

oil price drop have strong incentives

not to pullback on drilling activities.

These companies will be reluctant to

let go of their core talent and especially

their highly trained and experienced

wellsite employees.

Another issue is how to win the

war for talent in the next decade.

Increasingly, work is ceasing to be a

place and more a state of mind. For

large numbers of people it can happen

at any time of day and in any place.

Executives who understand this and

equip their organizations to survive

in this new world will be the ones

still leading successful oil and gas

companies in the next 30 years.

How much inflation do I believe is

baked into current oilfield service costs?

How much room do producers have to

lower their capital and operating costs

in the near term? You can answer that

question by asking: what will be the

global demand for power? If there is

a consistent demand for more power,

there will be demand in the energy

sector to deliver sustainable and robust

energy supply through engineering

expertise and independent technical

assurance. If the present conditions

hold, then efficiencies have to be

looked at without downgrading on

safety issues.

Outlook for Young Professionals

The use of data is going to change

how we do things in the future. But

it will mean new ways of working,

new collaborations, and our thinking

about different disciplines. Chemical

engineers will work with civil and

electronic instrumentation engineers,

working with mathematicians looking at

algorithms and using statistical analysis.

There are different mindsets across the

industry and it is going to require very

different thinking to create the smart

and sustainable oil and gas industry

of tomorrow’s world.

Our new generation of engineers,

in particular, have had experiences

as customers, which influence their

expectations in other business

dealings, such as their interactions

with their employers. This means

that digital communication

capabilities are becoming a key

weapon in recruiting and retaining

talent as well. Gone are the days

when an employee enthusiastically

received their new work laptop and

mobile phone. Today’s employees more

often than not have more information

communications technology at their

personal disposal than they are given

at work and information technology

departments are increasingly seen as

a limitation to their needs rather than

an enabler.

Organizations must understand

the best way to enhance communication

capabilities for their employees. For

most companies, this will not involve

handing out tablets or iPads to each

employee, but it should involve,

at a minimum, setting up internal

social networking and knowledgesharing sites. This approach will also

increase productivity as processes

previously requiring several

stages are completed in one or

two stages.

Likewise, organizations

need to look at the “complete”

package which they offer workers.

Reward is part of this—but what

employees are engaged with,the

environment in which they work,

and the opportunities for growth and

development are fundamental. There

is a clear trend that the engineers of

tomorrow are less purely motivated

by the sole financial rewards,

and the ethics and the ethos

of an organization are

equally important. TWA

Part 2: Judith Dwarkin, ITG Investment Research

As energy in all its forms is

essential to both economy and

life in general, the challenges

associated with finding, harvesting,

distributing, and using it efficiently

and responsibly are enduring. And

whether the current downturn in

the global oil market is, or is not, a

watershed moment, it is important

to remember that as an industry

professional you have been presented

with a massive summons to action, which

also comes with a massive opportunity

to shine.

I was raised in Fernie, British

Columbia, Canada, a small coal mining

and lumber town in Western Canada

well acquainted with commodity cycles.

Vol. 11 // No. 2 // 2015

11

Pillars of the Industry

After completing my undergraduate

and master’s degrees, I travelled

to Australia on a Commonwealth

scholarship to pursue a PhD in natural

resource economics.

During my academic career, I

became interested in public policy

and commodity markets and on

returning home to Western Canada

after graduating, I was fortunate to find

a way to pursue both these topics at the

Alberta Department of Energy. At the

time, the provinces and Canada’s federal

government were in the process of

dismantling a plethora of energy policies

and regulations that imposed various

types of controls on domestic oil and gas

upstream development and markets, as

well as internal and external trade. This

period of deregulation was a dynamic

and challenging time to work on energy

policy and, as it turned out, a great entry

point for my career in the industry.

One of my first assignments was

to help construct the oil and gas price

forecasts the Alberta government

used to develop its annual operating

budgets—a rather fraught task, and

equally fraught today.

Challenges for the Industry

It seems to me that through successive

episodes of oil and gas price crashes

and recoveries in the past few decades,

the industry has rebuilt itself a bit

smarter each time, making it better

able to ride out the next set of twists and

turns on the commodity roller coaster.

I have experienced four major oil price

collapses during my career in the

industry and cannot say that any specific

technical or analytical skill set is better

than the other at weathering the storm.

At a minimum, understanding exactly

what is required of you in your job is

essential, as obvious as this sounds.

While you, of course, are expected to

make a positive contribution to your

organization in the best of times, you

need to do this in spades during the

worst of times.

An irony in the oil and gas industry

is that one of the biggest tasks that

comes on the heels of the recoveries

that follow the downturns is the need

to rebuild depleted ranks of skilled

and knowledgeable staff. The degree

of technical specialization within the

industry tends to make this very hard to

do, particularly when previously laid-off

employees have since redeployed to

other sectors. But as I mentioned, I think

the industry is getting smarter about

managing this. As well, I believe a better

understanding of the nature of oil and

gas markets today is bringing a longerterm perspective to positioning for the

cyclical and structural forces at work in

these markets. Most people now realize

that making good decisions takes a more

nuanced approach than simply adopting

a point forecast or extrapolating today’s

situation into the future.

Other challenges for the oil and

gas industry in recent years have

come on the regulatory front. From

the wellhead to the tail pipe and

burner tip, environmental standards

and regulations have become more

numerous and more stringent.

Objections to these standards and how

regulators apply them are proliferating

Judith Dwarkin is the chief energy economist at ITG

Investment Research in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. ITG

Investment Research was formerly known as the Ross Smith

Energy Group. Prior to joining Ross Smith, Dwarkin was

senior vice president for Global Energy at the Canadian

Energy Research Institute where she managed the domestic

and international research programs pertaining to crude oil

markets and prices. Before that, she was a managing director

with the Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission, being responsible for oil and gas

market analysis and energy regulatory interventions on behalf of the Alberta

government. Dwarkin holds BA, MA, and PhD degrees in economics.

12

from interest groups previously

much less active in this arena. As a

consequence, the regulatory process

has become more complex and timeconsuming and, to some extent, more

unpredictable. Inevitably, this has

also resulted in decisions about largescale, and sometimes more innocuous,

energy projects becoming very

politicized—always a scary proposition

to an economist!

Outlook for Young Professionals

I have no doubt the energy industry will

continue as an engaging and dynamic

place for young professionals to craft

their careers. As with any profession,

however, doing well will take effort and

perseverance—as well as a dollop of

good luck and good timing.

Being able to think critically is

important. Having the analytical tools to

make sense of reams of data is essential.

Learning how to distinguish what is

interesting from what is relevant is

basic—fortunately, this task gets easier

with experience.

Learning how to communicate

your thoughts and findings clearly and

professionally is vital. Endeavoring

to learn as much as you can, as fast

as you can, and figuring out how

to apply it in your job is a way to

stand out.

Paying attention to what your boss

pays attention to is smart; anticipating

what he or she might want to pay

attention to is smarter. And summoning

an ounce of courage from time to time to

take a chance and do something that is

daunting for you is necessary, if you wish

to move forward.

Lastly, regardless of your area of

expertise within the energy sector, if

you find yourself in a leadership position

one day, you doubtless also will find

yourself having to think about issues

and make decisions incorporating the

perspectives of not just your own, but

several different disciplines—including

economics. When you get to this point,

let me know. TWA

Economist’s Corner

Commodity Price Cycles:

Explained by an Expert

Gürcan Gülen, University of Texas at Austin

Oil and natural gas are the lifeblood

of modern economies. Together, they

account for close to 60% of global

commercial energy consumption.

Even in future scenarios with a high

penetration of alternative energy

sources or technologies, oil and gas are

expected to maintain a share of about

50% by the middle of this century; more

business-as-usual scenarios forecast a

share of 60% or more.

The transportation sector depends

on oil products such as gasoline,

diesel, bunker fuel, and jet fuel almost

exclusively. The ability to travel and

ship goods are the key ingredients

for a successful economy; the lack of

transportation infrastructure or its low

quality has often been a major roadblock

for emerging economies to attract

investment. It will be difficult and timeconsuming to switch millions of vehicles

on land, sea, and air to alternative fuels.

None of the alternatives, including

biofuels, electric cars, and fuels derived

from natural gas, appears to be ready

to replace oil products in necessary

scale although they are certainly

making progress.

What is the Interplay

Between Oil, Natural Gas,

and Alternatives?

Natural gas is an important feedstock

in many industrial processes such as

methanol or fertilizer plants, but the

growth in gas use has come primarily

from the electric power sector, where it

has been replacing oil and other fuels

(primarily coal) in many countries, in

addition to meeting new demand growth.

In some markets, more than half of the

electricity is generated in gas-fired

power plants. The share of natural gas

in power generation is expected to

increase in most countries as countries

try to lower their emissions and as more

gas resources are proven and developed

across the globe.

The fact that gas-fired power plants

are relatively cheap and quick to build

has been and will likely continue to be

a key driver of this transition to natural

gas in the electric power sector. Another

driver is the shipping of natural gas in

liquefied form, or LNG, as it facilitates

the increased use of gas in more markets

around the world. The number of LNGimporting countries and regasification

Gürcan Gülen is a senior energy economist at the Bureau of

Economic Geology’s (BEG) Center for Energy Economics

(CEE) at the University of Texas at Austin, where he

investigates and lectures on energy value chain economics

and commercial frameworks. He has been working in BEG’s

interdisciplinary team to assess shale gas and oil resources

in the US and CEE’s natural-gas demand assessment in the

electric power, industrial, and transportation sectors. Gülen

has worked on oil, natural gas, and electric power projects in North America, South

Asia, West Africa, and the Caucasus among others, focusing on the economics,

policy, and regulation of resource development and delivery, and power market

design. He served in the US Association for Energy Economics (USAEE) in various

positions and was the editor of USAEE Dialogue for several years. Gülen is a USAEE

Senior Fellow and a member of SPE, American Economic Association, and Gulf

Coast Power Association. He received a PhD in economics from Boston College and

a BA in economics from Bosphorus University in Istanbul, Turkey.

capacity tripled while the number of

LNG-exporting countries and volume

of trade more than doubled since the

early 2000s. The low natural gas prices

in the US in recent years, mainly a result

of the “shale revolution,” encouraged

many LNG-export projects; however, low

oil prices reduce the competitiveness

of these projects. Construction at the

Sabine Pass terminal started in August

2012, and Cameron and Freeport in

late 2014. Others might be delayed or

canceled altogether.

The increasing shares of alternative

technologies, including renewables

such as wind and solar, and the possible

resurgence of nuclear power generation

are often seen as threats to the market

share of natural gas. However, the

capital cost of wind, solar, and nuclear

remains high relative to that of gas-fired

plants. In addition, wind and solar are

intermittent sources of generation, which

limits the share of these technologies

in making a power grid operate within

the reliability standards. Storage of

generated electricity can mitigate the

problem of intermittency. There are

several storage technologies under

development and some are commercial

or near-commercial projects. However,

the sector is still in its infancy and there

have been technology and commercial

failures. Once commerciality is proven,

developing enough capacity to matter for

the market shares of different fuels will

take time.

Although there is a level of dichotomy

between oil-exporting and -importing

countries, generally speaking, “lower”

oil and gas prices provide a boost to the

world economy. High oil prices triggered

recessions in the past, especially in

those countries that depend heavily on

oil imports. Often forgotten, however,

is the fact that prices were high at least

partially because of demand increasing

Vol. 11 // No. 2 // 2015

13

Economist’s Corner

faster than supply, and that demand

started increasing faster because oil was

“too cheap” for some period.

Globally, the price of natural gas

delivered by pipelines or as LNG

is linked to the price of oil through

formulas. The oil price could be a

reflection of a basket of crudes, or the

price of an oil product such as fuel oil.

This pricing is a historical remnant of the

long-term contracts needed to develop

long-distance pipelines and LNG value

chains but still reflects the energy

security concerns of major importers

such as Japan, which is dependent on

imports for almost all of its energy needs.

High oil prices hurt such importers more

as natural gas price also increases,

whereas low oil prices help their trade

balance more because gas imports also

cost less.

In the US, natural gas and oil prices

are mostly independently determined

in their own markets, even though there

are complex and indirect linkages to the

prices of byproducts such as ethane and

propane, the cost of drilling services,

and the substitution of fuels. For example,

current low oil prices have led to a drop

in drilling activity, which can possibly

lead to service companies reducing the

fees for their rigs and related services,

as well as suppliers of pipes and other

field equipment decreasing their prices.

This reduction in upstream costs might

encourage more gas wells to be drilled

at lower natural gas prices.

Why did the Price of Oil Spike

in 2008 and Remain High

Between 2009 and Late 2014?

These boom-bust cycles result primarily

from the inherent time inconsistency

between business cycles and the

investment cycle of upstream projects,

which can be as long as 10 years for

conventional projects. The rapid and

large economic growth experienced in

“emerging” economies, led by China,

in the early 2000s led to a significant

increase in demand for oil products,

but the industry was not ready to supply

the required amounts. This “excess

demand” situation resulted in increasing

prices, which culminated in a significant

14

spike in the first half of 2008. The

economic crisis that hit the world in the

second half of 2008 was partially caused

by these surging energy prices in

addition to excesses in financial markets

and fundamental macroeconomic

weaknesses in many economies, mostly

in Europe. The ensuing destruction of

demand for oil coincided with increased

production capacity, which was the

industry’s response to rising prices

earlier in the decade. This “excess

supply” situation led to a price collapse

in 2009. However, oil prices recovered

by 2010 and remained relatively high,

albeit not as high as in early 2008, until

collapsing again in late 2014.

Clearly, there are factors other than

the demand and supply fundamentals

that impact the price, although eventually

these fundamentals govern the price

formation. In the short term, even the

demand and supply fundamentals are

not fully transparent. Moreover, market

players have asymmetric information

regarding these fundamentals such as

the production capacities of different

countries (especially the “spare”

capacity in the member countries of the

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting

Countries—in essence, Saudi Arabia),

consumption levels and demand growth

in various markets, amount of crude oil

and products in storage, and energy and

environmental policies across the world.

The great majority of the world’s

oil resources are controlled by

governments, often via national oil

companies (NOCs). Their data are often

not publicly available, or if available,

they are untimely, insufficient, and

questionable in quality. This paucity

of data regarding resources and NOC

operational and financial performance

is probably one of the most significant

challenges facing analysts trying to

understand long-term prospects of

the global oil supply. Government

policies to subsidize petroleum

products inflate demand in many

countries; during economic crises,

many governments cannot afford the

subsidies, the reduction of which further

contributes to price cycles. Otherwise,

subsidies induce black market activity,

which can be significant in parts of

Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast

Asia, accounting for large volumes

when aggregated.

In addition, geopolitical factors

and financial trading of “paper

barrels” contribute to volatility and

cycles. For example, among the most

commonly cited reasons for the price

spike of 2008 is the increased amount

of money invested in commodity

trading by relatively new players

in this space (institutional investors

such as hedge funds and index

funds). Some also pointed to several

important geopolitical developments

including Venezuela stopping

supplies to ExxonMobil in February

2008, pipeline bombings in Iraq in

March 2008, labor strikes in Nigeria

and Scotland in April 2008, militant

attacks on facilities in Nigeria from

April through June 2008, and reports

of declining Mexican exports. Such

outages can have a disproportionately

large impact depending on the

quality of crude production lost, given

refinery specifications and emission

requirements for fuels in various

markets. For instance, lost production

of light sweet Nigerian crude could not

be readily compensated by heavy sour

crude from Saudi Arabia even though the

latter’s production capacity is sufficient.

Also of note are macroeconomic

policies and developments. In particular,

some analysts pointed to expansionist

monetary policies and associated

low interest rates as well as the weak

US dollar as factors contributing to

the rise of the oil price during the

period leading up to the spike of 2008.

Expansionist policies fuel demand, and

the weak dollar forces producers to

raise their prices to maintain revenues in

purchashing power terms. Consistently,

some believe that the increased strength

of the dollar is contributing to the price of

oil remaining low in early 2015.

The same factors are also behind the

quick recovery of the oil price after the

2009 collapse. Geopolitical concerns

include the string of upheavals in the

Middle East (commonly referred to as

the Arab Spring), the collapse of the

TWA Interview

Continued from page 7

ancien régime in Libya, the Russian

aggression in Ukraine, continuing

problems in Nigeria and Venezuela, and

violence in Syria and parts of Iraq. With

such uncertainties, trading tends to add