Lesson 10.3 changes in state

advertisement

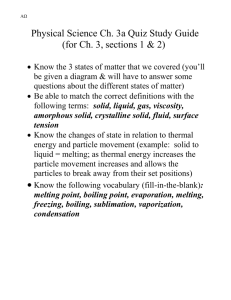

Lesson 10.3 Changes of State Suggested Reading Zumdahl Chapter 10 Section10.8 Essential Questions How do substances transition from on phase to another? Learning Objectives Define the following terms: vaporization, enthalpy of vaporization (∆Hvap), condensation, sublimination, enthalpy of fusion (∆Hfus), melting point and boiling point. Identify the trends observed in heating curves. Calculate the energy of phase changes from heating curves. Define phase diagram, critical temperature, critical pressure, critical point and triple point. Interpret phase diagrams. Introduction In the last few lessons, we looked at the states of matter. Depending on the conditions, substances may change from one state of matter to another. A change of a substance from one sate to another is called a change of state or phase transition. In this lesson we will look at the different kinds of phase transitions and the conditions under which they occur. A phase refers to the particular state of a system. Basic Terms The students often confuse or terms listed below. Please make sure you understand each terms. Vaporization (Evaporation): The change of a solid or liquid to the vapor. ENDOTHERMIC since energy must be absorbed so that the liquid molecules gain enough energy to escape the surface and thus overcome the liquid’s IMFs. Enthalpy of vaporization (∆Hvap,heat of vaporization): The heat needed to vaporize one mole of a liquid. Condensation: The changed of a gas to either the liquid or the solid sate. Water’s heat of vaporization is 40.7 kJ/mol. This is huge! Water makes life on this planet possible since it acts as a coolant. The reason its ∆Hvap is so large has everything to do with hydrogen bonding. The IMFs in water are strong, so a great deal of the sun’s energy is needed to evaporate the rivers, lakes, oceans, etc. of Earth. Perspiration is a coolant for animals possessing sweat glands. Energy from your hot body is absorbed by the water and evaporates. Sublimination: The change of a solid directly to the vapor. Enthalpy of fusion (∆Hfus, heat of fusion): The heat needed to melt one mole of a solid (Melting is also called fusion in chemistry, just to create some confusion). Melting point: The temperature at which a crystalline solid changes to a liquid or melts. Boiling point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the pressure exerted on the liquid (usually by the atmosphere). In general, each of the three states of matter can change into either of the other two states: Vapor Pressure Liquids, and some solids, are continuously vaporizing. If a liquid is in a closed container with space above it, a partial pressure of the vapor state builds up in this space. At the same time the rate of condensation starts to increase. Equilibrium vapor pressure (VP) is reached when the molecules leave and enter the liquid phase at the same rate. The VP of a liquid can be measured easily using a simple barometer. A small sample of the liquid is introduced into the Hg column of a barometer. Being less dense than Hg, the liquid rises to the top of the Hg and begins to evaporate. The Hg column drops a distance h because of the VP. Volatile liquids have high VPs, thus weak IMF's. These liquids evaporate readily from open containers since they have so little attraction for each other. This requires little energy; the heat energy absorbed from a warm room is usually enough to make these substances evaporate quickly. If you smell an odor to a substance when you open the bottle, it means the molecules have been banging against the lid wanting out! VP increases significantly with T! Heat ‘em up, speed ‘em up, move ‘em out! Increasing the temperature increases the KE which facilitates escape AND the speed of the escapees! As molecules at the surface gain sufficient KE (through collisions with neighboring molecules) they escape the liquid. More molecules can attain the energy needed to overcome the IMFs in a liquid at a higher T since the KE increases. In general, as MM ↑ VP ↓ As molecules increase in molar mass (MM), they also increase in the number of electrons. As the number of electrons increase, the polarizability of the molecule increases so more induced dipole-induced dipole (dispersion forces) exist, causing stronger attractions to form between molecules. This decreases the number of molecules that escape and thus lowers the VP. Water is an exception. It has an incredibly low VP for such a light molecule due to the strong hydrogen bonding IMFs. Boiling Point and Melting Point Now that we have looked at VP lets revisit the definition for boiling point. Boiling point is defined as the temperature at which the VP of a liquid equals the pressure exerted on a liquid (atmospheric unless in a closed container). As the T of a liquid is raised, the VP increased. When the VP = Patm, stable bubbles of vapor form within the body of the liquid. This process is called boiling. Once boiling starts, the temperature of the liquid remains constant, so long as sufficient heat is supplied. Because the pressure exerted on a liquid can vary, the BP can vary. The normal BP of water is at 1 atm. However, at high altitudes where the Patm is less, the BP is also less. This is why you sometimes find high-altitude cooking instructions of foods. The T at which a pure liquid changes to a solid is called the freezing point (FP). The T at which the solid changes to a liquid is called the melting point (MP). FP & MP are identical because melting and freezing occur at the T where the liquid and solid are in equilibrium. Unlike BP, MP and FP are only affected by large pressure changes. Furthermore, both MP and FP are characteristic properties of a substance that can be used to identify it. Heating Curves Any change of state involves the addition or removal of energy as heat to or from the substance. A heating curve is a graph that shows the phase changes that occur as heat is added to a system at a constant rate. You can see from the curve on the right, that the substance transitions from solid, to liquid, to gas in a series of positive slants and flats. This is characteristic of all heating curves. The slants show the increase in T as the substance moves from one phase to the next and the flats represent a phase transition. The T is constant during a phase transition because the system is in equilibrium. However, energy is continually added, so eventually the system's T begins to increase again, and the system moves away from equilibrium and toward the next phase change. On the plateaus, ∆E = q = ΔH(vap or fus) × n, where n is moles On the slants, ∆E = q = m × c(liquid, solid, or gas) × T Notice that the lengths of the flat regions vary. Because heat is being added at a constant rate, the length of each flat region is proportional to the heat of phase transition. Heat of fusion (∆Hfus, enthalpy of fusion): The heat needed to melt one mole of solid. For ice the heat of fusion is 6.01 kJ/mol. H2O(s) → H2O(l); ∆Hfus = 6.01 kJ/mol Heat of vaporization (∆Hvap, enthalpy of vaporization: The heat needed to vaporize one mole of liquid. For water, H2O(l) → H2O(g); ∆Hvap = 40.7 kJ/mol Not that much more energy is required for vaporization than form melting. This is because the relative strengths of the IMFs are about the same for liquid and solid water. Melting only needs enough energy for the molecules to escape form their sites in the lattice. For vaporization, enough energy must be supplied to break most of the IMFs. Example: Calculating the heat required for a phase change of a given mass of substance. A particular refrigerator cools by evaporating liquified dichlorodifluoromethane, CCl2F2, How many kg of this liquid must be evaporated to freeze a tray of water at 0∘C to ice at 0∘C? The mass of the water is 525 kg, the heat of fusion of ice is 6.01 kJ/mol, and the heat of vaporization of dichlorodifluoromethane is 17.4 kJ/mol. Solution: We want to transition from a liquid to a solid, so the water must move down the heating curve, which requires the removal of energy in order to cool the liquid to freezing. First, we must convert grams of water to mole. The minus sign indicates that heat energy is taken away from the water. This result show that CCl2F2 must absorb -175 kJ of heat for the water to freeze. The mass of CCl2F2 that must be vaporized to do this is 1.22 kg must be evaporated. Phase Diagrams A phase diagram is a graphical way to summarize the conditions under which the different states of a substance are stable in a closed system. Phase diagrams exist in a variety if 2-D and 3-D forms. They are used in numerous applications and help us to make predictions about how a material will behave under different conditions. Here are the basics. Melting-Point Curve The phase diagram for water consists of three curves that divide the diagram into regions representing the different states. In each region, the indicated state is stable. Every point along the curve represents the experimentally determined temperatures and pressures at which two states are in equilibrium. Thus, the curve AB divided the solid and liquid regions, and represents the conditions under which the solid & liquid are in equilibrium. This point give the melting points of the solid at various pressures, and is often called the melting-point curve. Since MP is only slightly affected by P, the MP curve is almost vertical. If the liquid is more dense than solid, as is the case for water, the MP decreases with P (curve leans left). For most substances, the liquid state is less dense than the solid, and the cure leans right (MP increases with P). Vapor-Pressure Curves for the Liquid and Solid The curve AC divides the liquid and gaseous regions, and gives the vapor pressures of the liquid at various T & P. It also gives the boiling points of the liquids for various T & P. The curve AD divides the solid and gaseous regions, and gives the vapor pressure of the solid at various T & P. Point A, where all curves meet, is called the triple point. The triple point is the point on a phase diagram representing the temperature and pressure at which three phases of a substance coexist in equilibrium. For water, the triple point occurs at 0.01°C, 0.0063 atm, and the solid, liquidm and vapor phases coexist. Critical Temperature and Pressure The temperature above which the liquid sate can no longer exist is the critical temperature (Tc). On the phase diagram pictured right this is the denoted by point B. Notice that the vapor-pressure curve disappears at this point. The vapor-pressure at the critical temperature is called he critical pressure (Tp). The critical point is where the critical temperatures and pressures intersect. Many important gases cannot be liquified at room temperature. Nitrogen, for example, has a critical temperature of -147 °C. This means that it cannot be liquefied until the temperature is below -147 °C. Supercritical Fluid Lets let Martyn tell you about supercritical fluids. He knows a lot more about them than I do. Watch this You Tube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yBRdBrnIlTQ Homework: Book questions pg 476 questions 37-40, 91 Study Guide book questions pg 233 questions 1-10, 44-53, 65