Affidavit : Du Plooy - The Arms Deal Virtual Press Office

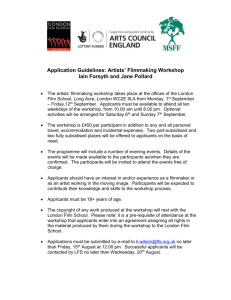

advertisement