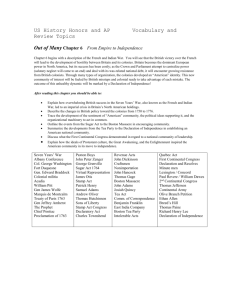

Chapter 4 Overview - Bishop McGann

advertisement

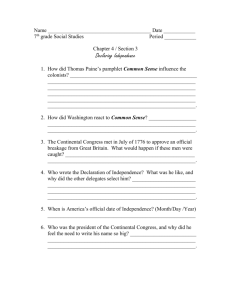

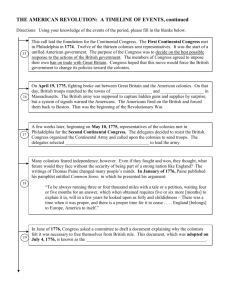

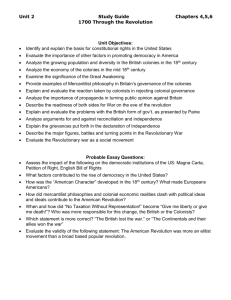

CHAPTER 4 The American Revolution CHAPTER OVERVIEW “The Shot Heard Round the World.” Although the names of the founders of the American republic have taken on iconic status, at the time they undertook a revolution against British rule, they did not know if it would succeed. In the midst of a war against Great Britain, they attempted to create a new government and a new nation. The actions of the First Continental Congress led the British government in January 1775 to decide on the use of force to control the colonies. In April, British troops moved to seize arms the Patriots had stored at Concord. Forewarned, a group of Minute Men met the British at Lexington, where an exchange of gunfire left eight Americans dead. The British moved on to Concord and destroyed the provisions stored there. On their way back to Boston, however, British troops encountered withering fire from irregulars along their line of march. Other colonies rallied quickly to support Massachusetts. The Second Continental Congress. The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on May 10. More radical than the First Congress, this meeting included a particularly distinguished group. It organized the forces gathering around Boston into a Continental Army and appointed George Washington commander-in-chief. The Battle of Bunker Hill. While Congress met, the Patriots set up defenses on Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill overlooking Boston. Two assaults by the Redcoats failed to dislodge the colonists from Breed’s Hill. The British carried the hill on their third try. The battle, however, cost the British more than twice the number of colonial casualties. It also reduced chances for a negotiated settlement. George III proclaimed the colonies to be “in open rebellion.” The Continental Congress appeased moderates by offering one last plea to the king and then adopted the “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms.” Congress also proceeded to order an attack on Canada and set up committees to seek foreign aid and to buy munitions abroad. The Great Declaration. Congress, and most colonists, hesitated to break with Britain. Some undoubtedly worried about their fate should they lose. Others, concerned by the actions of mobs during the protests against the Stamp Act and the Tea Act, wondered what might replace British rule. Nevertheless, two events in January 1776 pushed the colonies toward the final break: the British decision to use Hessian mercenaries and the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. Paine called for complete independence and attacked the idea of monarchy. Nearly everyone in the colonies must have read or heard about Paine’s pamphlet. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution declaring independence from England on June 7, 1776. Congress did not act at once; it appointed a committee to draft a justification for Lee’s resolution. Congress adopted the justification, written largely by Thomas Jefferson, on July 4. The first part of Jefferson’s Declaration described the theory on which the Americans based their revolt and their creation of a republican government. The second part consisted of an indictment of George III’s treatment of the colonies. 1776: The Balance of Forces. Americans enjoyed several advantages in their fight for independence. Americans fought on familiar terrain; England had to bring forces from across the Atlantic; England’s highly professional army was ill-directed; and public opinion in England was divided. Britain, however, possessed superior resources: a much larger population, large stocks of war materials, industrial capacity, mastery of the seas, a trained and experienced army, and a highly centralized government. Moreover, Congress had to create new political institutions during a war. Loyalists. America was far from united. Loyalists, or Tories, constituted a significant segment of the colonial population. Historians’ best guess is that a fifth of the population remained Loyalists, as opposed to two-fifths who were Patriots. Differences separating Tories from Patriots were not clearly defined; however, a high proportion of those holding royal appointments and many Anglican clergymen remained loyal to the Crown, as did some merchants with ties to Britain. Whatever their strength, Loyalists lacked organization and effective leadership. The British Take New York City. General Howe defeated an inexperienced American army at the Battle of Long Island and again on Manhattan Island. In both instances, however, he failed to follow up his advantage and allowed Washington’s army to escape. Washington learned from his defeats and forged his men into an army. Washington surprised a group of Hessian mercenaries by crossing the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776, and attacking at daybreak. A second victory at Princeton on January 3, 1777, further bolstered American morale. Saratoga and the French Alliance. The British planned an elaborate three-pronged attack to crush the colonial resistance. After wasting time trying to trap Washington’s army, Howe moved to attack Philadelphia. Although he defeated Washington at the Battle of Brandywine and moved unopposed into Philadelphia, Howe’s adventures doomed the British campaign. American forces dealt General Burgoyne a devastating defeat at Saratoga. At this point, France, which had not reconciled itself to its defeat in the Seven Years’ War and had been giving aid to the Americans, recognized the United States. The United States and France negotiated a commercial treaty and a treaty of alliance. Recognizing the danger of that alliance, Lord North proposed giving in on all issues that had roused the colonies to opposition, but Parliament delayed until after Congress had ratified the treaties with France. War broke out between France and Britain. After the loss of Philadelphia, Washington settled his army at Valley Forge for the winter. There, the army’s supply system collapsed, and the men endured a winter of incredible hardship. Many officers resigned. Enlisted men, who did not have that option, deserted. Yet the army survived. The War Moves South. In May 1778, the British replaced General Howe with General Clinton. Washington and Clinton fought an inconclusive battle at Monmouth Court House, but Americans held the field and could claim victory. After this, fighting in the North diminished. The British focused their attention on the South, hoping that sea power and the supposed presence of a large number of Tories would bring them victory. The British took Savannah and Charleston; however, guerrilla bands continued to harass the British forces. Congress finally permitted Washington to replace Gates with Greene, who avoided major battles with Cornwallis’s larger army and bedeviled Cornwallis with a series of raids. American forces won victories at King’s Mountain, Cowpens, and Guilford Court House. Cornwallis withdrew to Wilmington, North Carolina, where he could rely on the British fleet for support. Victory at Yorktown. Clinton ordered Cornwallis to establish a base at Yorktown, where he could be supplied by sea. However, the French fleet cut off Cornwallis’s supply and escape routes, and French and American ground forces closed the trap. Cornwallis asked for terms on October 17, 1781. Negotiating a Favorable Peace. Despite a promise to France not to make a separate treaty, American negotiators successfully played off competing European interests and obtained a highly favorable treaty with Britain. Britain recognized American independence, established generous boundaries, withdrew its troops from American soil, and granted fishing rights. In the final analysis, Britain preferred to have a weak English-speaking nation control the Mississippi Valley rather than France or Spain. National Government Under the Articles of Confederation. Congress was a legislative body, not a complete government. Various rivalries, particularly over claims to western lands, delayed the adoption of the Articles of Confederation. The Articles created a loose union. Each state retained its sovereignty, and the central government lacked the authority to impose taxes or to enforce the powers it possessed. Financing the War. Congress and the states shared the financial burden of the war. Congress supported the Continental Army, while the states raised militias. Even though the states did not honor all of Congress’s requisitions for funds, they did contribute $5.8 million in cash and more in supplies. Congress also raised large sums by borrowing. Both Congress and the states issued paper money, which caused the currency to fall in value. The people paid for much of the war through the depreciation of their money and savings. Robert Morris became superintendent of finance and restored stability to currency. State Republican Governments. Most states framed new constitutions even before the Declaration of Independence. The new governments did not differ drastically from those they replaced. While they varied in detail, all new charters provided for an elected legislature, an executive, and a system of courts. In general, the power of the executive and courts was limited; power resided in the legislature. The various systems of government explicitly rejected the British concept of virtual representation. Legislators represented the interests of a particular district. A majority of state constitutions also contained bills of rights, which protected civil liberties against all branches of government. The idea of drafting written structures of government derived from dissatisfaction with the vagueness of the unwritten British constitution and represented one of the most important innovations of the Revolutionary era. Social Reform and Antislavery. Many states used the occasion of constitution making to introduce social and political reforms, such as legislative reapportionment and the abolition of primogeniture, entail, and quitrents. Jefferson’s Statute of Religious Liberty, enacted in 1786, separated church and state in Virginia. Many states, however, continued to support religion. A number of states moved tentatively against slavery. All northern states provided for the gradual abolition of slavery, and most southern states removed restrictions on manumission. Americans were hostile to the granting of titles and other privileges based on birth. Yet little social or economic upheaval accompanied independence. While more people of middling wealth won election to legislatures than in colonial times, high property qualifications for office holding remained the general rule. Nevertheless, the new governments were more responsive to public opinion. Women and the Revolution. The late eighteenth century saw a trend toward increasing legal rights for women. For example, it became somewhat less difficult for women to obtain divorces. Still, the change in attitudes was relatively small. The war did increase the influence of women. With so many men in the army, women managed farms, shops, and businesses. Revolutionary rhetoric stressed equality and liberty, and some women applied it to their own condition. The Revolution also provided for greater educational opportunities for women. The republican experiment required educated women, not only because women were citizens, but because women were responsible for raising the welleducated citizens necessary to the republic. Growth of a National Spirit. While most modern revolutions have been caused by nationalism and have resulted in independence, the desire to be free antedated the American Revolution, which gave rise to nationalist sentiments. The colonies united not out of a desire for political unity but because union offered the only hope of defeating the British. Although by the middle of the eighteenth century colonists had begun to think of themselves as distinctively American, little political nationalism existed before the Revolution. Nationalist sentiment came from a variety of sources: common sacrifices in war, common experiences during the war, service in the Continental Army and exposure to soldiers from other colonies, soldiers traveling with the army to different places, and legislators traveling to different parts of the country and listening to ideas of people from different areas. Local interests and loyalties remained strong, but certain problems demanded common solutions. Maintaining thirteen separate postal systems or thirteen sets of diplomatic representatives was simply not practical. The Great Land Ordinances. The Land Ordinance of 1785 provided for surveying western territories. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established governments for the west and provided a mechanism for the admission of the territories as states. Territorial governments resembled British colonial governments in structure, but this was only a step toward statehood, not a permanent arrangement. National Heroes. The Revolution provided Americans with their first national heroes. Benjamin Franklin was well-known before the Revolution, and his support of the Patriot cause added to his fame. George Washington, however, became “the chief human symbol” of the Revolution and of a common Americanism. A National Culture. The political break with Britain accentuated an already developing trend toward social and intellectual independence. The Anglican Church in America became the Protestant Episcopal Church. The Dutch and German Reformed Churches severed ties with Europe. American Catholics gained their own bishop. The textbooks of Noah Webster emphasized American forms and usage. Writers and painters chose patriotic themes. While most citizens continued to give their first loyalty to their states, they were also increasingly aware of their common interests and proud of their common heritage.