SHARON MCIVOR AND JACOB GRISMER v

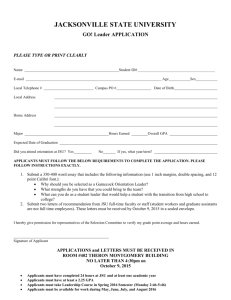

advertisement