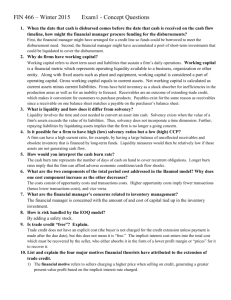

CHAPTER 13

advertisement

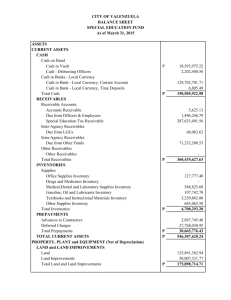

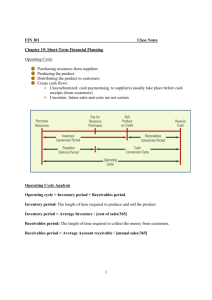

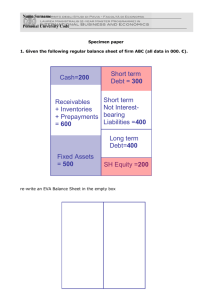

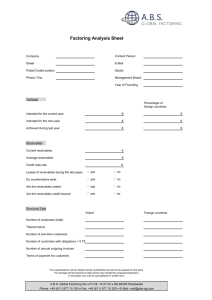

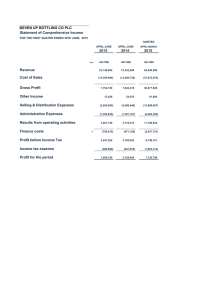

CHAPTER 13 It is useful to begin the discussion of working capital policy by reviewing some basic definitions and concepts. Working capital, sometimes called gross working capital, generally refers to current assets, while net working capital is defined as current assets minus current liabilities—the amount of current assets financed by long-term liabilities. The current ratio, calculated as current assets divided by current liabilities, is intended to measure a firm’s liquidity. A high current ratio does not insure that a firm will have the cash required to meet its needs. The best and most comprehensive picture of a firm’s liquidity position is obtained by examining its cash budget, which forecasts a firm’s cash inflows and outflows. It focuses on what really counts, the firm’s ability to generate sufficient cash inflows to meet its required cash outflows. Working capital policy refers to the firm’s basic policies regarding target levels for each category of current assets and how current assets will be financed. We must distinguish between those current liabilities that are specifically used to finance current assets and those current liabilities that represent (1) current maturities of long-term debt; (2) financing associated with a construction program that after completed will be funded with the proceeds of a long-term security issue; or (3) the use of short-term debt to finance fixed assets. Even though we define long-term debt coming due in the next accounting period as a current liability, it is not a working capital decision variable in the current period. Similarly, when construction is temporarily financed with a short-term loan and later replaced with mortgage bonds, the construction loan would not be considered part of working capital management. Although such accounts are not part of the working capital decision process, they cannot be ignored because they are due in the current period, and they must be considered when the cash budget is constructed and the firm’s ability to meet its current obligations is assessed. A firm’s current asset levels and financing requirements rise and fall with business cycles and seasonal trends. At the peak of such cycles, businesses carry their maximum amounts of current assets. Similar fluctuations in financing needs can occur over these cycles; typically, financing needs decline during recessions but increase during booms. Once a firm’s operations have stabilized and cash collections from credit sales and cash payments for credit purchases have begun, the balance in accounts receivable and accounts payable can be computed using the following equation: Account = Amount of × Average life . balance daily activity of the account A decision affecting one working capital account will have an impact on other working capital accounts. The cash conversion cycle focuses on the length of time between when the company makes payments, or invests in the manufacture of inventory, and when it receives cash inflows, or realizes a cash return from its investment in production. The following terms and definitions are used: Inventory conversion period is the average length of time required to convert materials into finished goods and then to sell these goods; it is the amount of time the product remains in inventory in various stages of completion. Inventory Inventory = . conversion period Cost of goods sold 360 Receivables collection period is the average length of time required to convert the firm’s receivables into cash, that is, to collect cash following a sale. It is also called the days sales outstanding (DSO). Receivables = DSO = Receivables . collection period Credit sales 360 Payables deferral period is the average length of time between the purchase of raw materials and labor and the payment of cash for them. Accounts payable Payables . = DPO = deferral period Cost of goods sold 360 The cash conversion cycle, which nets out the three periods just defined, equals the length of time between the firm’s actual cash expenditures to pay for (invest in) productive resources (materials and labor) and its own cash receipts from the sale of its products. Thus, the cash conversion cycle equals the average length of time a dollar is tied up in current assets. Using these definitions, the cash conversion cycle is defined as follows: Inventory Receivables Payables Cash conversion = conversion + collection − deferral . period period period cycle To illustrate, suppose it takes a firm an average of 79.0 days to convert raw materials and labor to widgets and to sell them, and it takes another 43.2 days to collect on receivables, while 8.8 days normally lapse between the receipt of materials (and work done) and 2 payments for materials and labor. In this case, the cash conversion cycle is 79.0 days + 43.2 days – 8.8 days = 113.4 days. The firm’s goal should be to shorten its cash conversion cycle as much as possible without increasing costs or depressing sales. This would maximize profits because the longer the cash conversion cycle, the greater the need for external, or nonspontaneous, financing and such financing has a cost. The cash conversion cycle can be shortened (1) by reducing the inventory conversion period by processing and selling goods more quickly, (2) by reducing the receivables collection period by speeding up collections, or (3) by lengthening the payables deferral period by slowing down its own payments. When taking actions to reduce the inventory conversion period, a firm should be careful to avoid inventory shortages that could cause good customers to buy from competitors. When taking actions to speed up the collection of receivables, a firm should be careful to maintain good relations with its good credit customers. When taking actions to lengthen the payables deferral period, a firm should be careful not to harm its own credit reputation. Actions that affect the inventory conversion period, the receivables collection period, and the payables deferral period all affect the cash conversion cycle; hence, they influence the firm’s need for current assets and current asset financing. 3