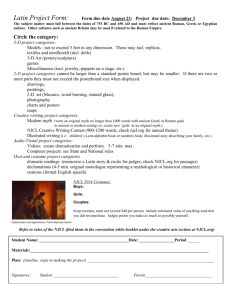

SBL proposal Greco-Roman Religions Section

advertisement

SBL proposal Greco-Roman Religions Section Abstracts Themed Session: ‘Mythmaking, Fictionalising, Entextualising: Creative Moments in Graeco-Roman Religious Reality.’ Gerhard van den Heever (University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa) Myth, Fiction, Text: Reading ‘Religion’ Between the Lines. Invoking myth, inventing tradition, and entextualizing/authorizing tradition are ageold technologies for producing authority and replicating hierarchies of ‘powerdissipations’. This paper argues that these are related operations that, as an ensemble, construct what is called ‘religious tradition’. Drawing on a range of theorists, from Bruce Lincoln to Eric Hobsbawm and Fredric Jameson, it is demonstrated how myths of creation and the consequent procession (or issuing) of gods are recontextualized in various ‘religious’ contexts with a view to establishing authority and powerhierarchies. Particular attention is paid to the Isis/Osiris-Dionysus complex spanning the period from Hellenistic Ptolemaic Egypt to Late Antiquity, traversing discursive genres such as large-scale performances and mime, to philosophical discourse, novelistic fiction and epic poetry (i.e., from Ptolemy II Philadelphos to Nonnos), and highlighting the persistence of the topos of arrival of gods/divine mediating agency even in such seemingly ‘independent’ traditions as early Judaisms and early Christianities with their simultaneous anchoring of the discourse of arrival of divine mediating agency in illo tempore and in historical circumstance. This paper is about the recalibration of myth, the textualization of invented tradition, and the resultant establishment of authoritative discursive formations. Redescription of Graeco-Roman mythic invention through comparative work in this vein, also answers the theoretical question: What is myth good for? Nancy Evans (Wheaton College, Norton, Massachusetts) From Mad Ritual to Philosophical Inquiry: Ancient and Modern Fictions of Continuity and Discontinuity. This paper will explore one of the more creative — and influential — moments of mythmaking and fictionalizing from the ancient Mediterranean world: the (re-) invention of prophetic madness. In particular, I will first look to the fictionalized encounter between two Athenians, Socrates and Phaedrus. Plato’s Phaedrus records their conversation, a talk that ranged over a vast terrain of topics ranging from homoerotic lovers to skilled (and less skilled) rhetoricians. In the midst of this dialogue Socrates famously interrupts himself, and invokes two powerful allies in his search for true speech: first the mythic tradition surrounding the fall of Troy, and then ancient rites of purification that facilitate human access to knowledge of the divine. In this context of his palinode Socrates investigates the links between prophecy and divine madness, and ultimately he applies the purported gifts of this madness to pursuits that are generally considered to be more rational. After a brief analysis of some of the rhetoric and syntax in Socrates’ palinode, I will open up the paper to examine the possibilities and complexities of identity in the Athens of Plato and Socrates. Multiple and overlapping social identities and cultic traditions are alluded to in the palinode; drawing from the work of Walter Burkert, Eric Hobsbawm, Bruce Lincoln and Jonathan Z. Smith I will examine how — and even whether — the multiple religious identities that lie behind this dialogue could be thought to advance and invent a tradition that came to be known as philosophy. Tennyson Jacob Wellman (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) Paradosis or Akoē? Or, Making a Tradition of an Ass. Damaskios’ Philosophical History includes the puzzling account of Zenōn the Alexandrian, a Jew who publicly joined the Platonist school and renounced his Judaism “in the traditional manner” by driving a white ass through a synagogue on the Sabbath. I will examine the resonances of this allegedly “traditional” ritual in a creative Late Antique environment situated between three religious identities whose overlaps and collisions were as significant as their differences. The social embedding of the event provides us with a range of actors involved: Zenōn, his Jewish audience, his Platonist colleagues, the wider public (including Jews, Hellenophones, and Christians) and Damaskios’ omniscient post-fact narrator. In producing a new “traditional” ritual which resituated the boundaries between groups that often overlapped, Zenōn, and Damaskios’ remembering of the event, drew on a repertoire of actions, symbols, and narratives to produce an event whose meaning was recursively rich and nuanced. The notion of “tradition” to which Damaskios refers is itself an ironic commentary on the relations between Christians and Jews, drawing on narratives of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, as well as common anti-Jewish calumnies to suggest the superiority of Platonic religious identities over Jewish ones. But Damaskios’ final comments on Zenōn’s character demonstrate that the convert’s social realignment with a Hellenic identity was contested even by his new colleagues, and the ass is recast as a type by which the reader can better understand the man. This foregrounds the tensions between traditionalism and innovation in a diverse and contested field of cultural production, and the problematic interplay of identities in a single figure. Zenōn’s “traditional” ritual marked precisely the moment when his world was changing and requiring innovation to handle those changes. Gail E. Armstrong (Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island) Sacrificial Iconography: Creating History, Making Myth, and Negotiating Ideology on the Ara Pacis. The Ara Pacis Augustae, dedicated in 13 B.C.E. and finished in 9 B.C.E., serves as a reflection of the Roman Senate’s participation in Augustus’ redescription of history. The iconography of the monument, with its pictorial language of peace, fertility, abundance, and piety, can be read as a text that engages with the history- and mythmaking of Augustus. It evokes texts such as Virgil’s Aeneid, and provides another, supportive narrative of the fictional history that established the power and authority of Augustus. In other words, the monument serves as the Senate’s recognition of the Augustan redescription of Roman history. This paper argues that the Ara Pacis functioned primarily as the Senate’s negotiation of its own role within the “new order” established by the Augustan myth but also secondarily, to identify itself as a continuing participant in the “field of cultural production” (Bourdieu). Indeed, it engages in its own history-making, in which it describes itself as an active partner in Augustus’ production of history and myth. The ritualization of sacrifice that we see depicted on the Ara Pacis serves to legitimate the power of Augustus and the power of the Senate as part of the new order. The senate is working within the new myth already laid out by Augustus and it utilizes the imagery and the ideology he has already established. The Senate might have “accepted” the Augustan redescription, but it also needed to situate itself within it, and thus it became an active participant in the process. The Ara Pacis, using the language of sacrifice and thereby of religion, serves to index Augustus and the imperial family, and the Senate as both producers and actors. Pieter J. J. Botha (University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa) The Quotidian of Mythology: Aspects of Place and Visual Environment in Redescribing Greco-Roman Antiquity. Two areas of the material world of the early Roman empire typically do not feature in descriptions of “religious experience”: Roman art and the Roman house. Both aspects are intricately saturated with myths and mythmaking. Consequently, an argument can be presented that the Roman domus is about more than simply private life. The remains of houses from the Empire are a major resource for investigating how people living within the Roman world thought of themselves and how they communicated this self-image to the world. Secondly, against the backdrop of the epochal transformations — both in the structure of society and in the individual’s relation to that structure — that mark the history of the Roman empire, the changes in the functions of art need consideration. The suggestion is to have a look at Roman art as both a key to, and reflection of Roman syncretism, and to relate a cultural phenomenon which brought together an extraordinary variety of races, nations, art forms, styles and cults in romanitas. It seems that we still underestimate how much “secular” space was determined by evocations of the sacred. In order to emphasise and manage such interrelatedness a reduction of historical scale to the description and understanding of everyday life and its multiformed ways of storytelling is required. This shift of focus is an attempt to transcend a sharp dichotomy opposing objective, material, structural, or institutional factors to subjective, cultural, symbolic, or emotional ones. It is an expression of the effort to join the historical, anthropological and sociological disciplines which have sharpened their focus towards the micro-scale by considering stories (myths) in action, storytelling not necessarily by means of formal literacy. Daniel Ullucci (Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island) Before Animal Sacrifice: A Myth of Innocence. Meat has always been part of the human diet. Within Greek and Roman religions (as well as many other religious systems worldwide), animal sacrifice was one of the most omnipresent and socially significant religious practices. Yet, numerous Greek and Latin writers tell of a golden age when humans were not dependent on killing animals for food. In this idealized world, humans lived at one with the gods, and animal sacrifice did not exist. One classic example of this myth comes from Porphyry’s De Abstentia. According to Porphyry, humans were originally vegetarians. When famine struck, people fell to cannibalism. The eating of animal meat and the ritual of sacrifice, he claims, emerged only as a substitute to murder and eating human flesh. Other stories of a golden age without sacrifice are found in Hesiod, Herodotus, Ovid, and others. These passages have often been read through the lens of the later Christian position on sacrifice. According to this view, animal sacrifice was a barbaric and senseless act which was abolished and replaced by the pure sacrifice of Jesus. In fact, Eusebius is aware of the same version of the myth Porphyry tells and uses it to support his rejection of sacrifice. Largely as a result of this Christian lens, scholars have not asked what the myth of a world without sacrifice means in a world in which sacrifice predominated. This paper seeks to correct the above view by analyzing these texts as instances of created myth. It approaches each occurrence of the myth as an instance of positiontaking by a player in the field of cultural production. The paper seeks to further a redescription of Greco-Roman antiquity by revealing the variety of ancient positions on sacrifice and their strategic use by competing cultural producers.