Unit 2: Early River Civilizations Reading Two: Egypt Source: World

advertisement

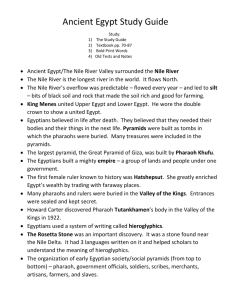

Unit 2: Early River Civilizations Reading Two: Egypt Source: World History: A Story of Progress. Ed. Terry L. Smart and Allan O. Kownslar. Holt, Rinehart and Winston; New York, 1987. P36-57. While Sumerian civilization was emerging in the Tigris-Euphrates River valley, similar developments occurred elsewhere-in the Nile River valley of Egypt. In this chapter you will learn how Egyptian civilization, its people united by the Nile River and protected by a barren desert, remained practically undisturbed by outsiders for hundreds of years. The geography of the Nile River valley differed from that of Sumer and, as you will see, helped give Egyptian civilization its own, unique character. Prehistoric Egypt The Egyptians developed a great civilization along the Nile River in the northeastern part of Africa. Although historians now believe that this civilization emerged after the Sumerians, both arose from a similar Neolithic background. During the Paleolithic Period when hunters roamed the northern part of Africa, it was covered with broad, rolling grasslands and many rivers. Gradually the climate became drier as the earth warmed after the most recent Ice Age, and the region became a desert. People were forced to move to places with a greater water supply. Some of them moved to the banks of the Nile and settled in the low desert that bordered the swamps of the Nile Valley. Ancient houses and cemeteries found in that area indicate that over a period of 4,000 years the swamps, once inhabited by crocodiles and hippopotamuses, were cleared and settled. As the swamps were cleared, Neolithic people began to farm the fertile land. Historians think that the first crops in Egypt were planted about 7,000 years ago. The prehistoric Egyptians learned to domesticate wild animals. They made tools from wood and stone, fashioned pottery on a rotating wheel, and worked with copper. They even learned to grow flax and weave the fibers into linen for clothing. Some prehistoric Egyptians engaged in limited trade. Popular trade items included materials used in the making of perfumes and goods made from copper and ivory. These early farmers formed villages along the Nile and built their homes of reeds and mud from the river banks. Remains of their cemeteries show that the Nile farmers buried their dead in shallow graves. The bodies were placed on their sides and the hot, dry sands of the desert often preserved the bodies for thousands of years. Pots, weapons, and food were usually found placed beside the deceased, suggesting that the prehistoric Egyptians believed in an afterlife. The Old Kingdom Historians divide Egyptian history into three main periods: the Old Kingdom (2850 B.C. to 2200 B.C.), the Middle Kingdom (2050 B.C. to 1792 B.C.), and the New Kingdom (1570 B.C. to 1090 B.C.). As you will see, these dates are only approximations because of the kinds of records the Egyptians kept. Historians do not have enough information to say exactly when each period began or to know precisely how long it lasted. The Uniting of Egypt Before the beginning of the Old Kingdom, Egypt was divided into two separate kingdoms called Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. (See map) A king of Upper Egypt named Menes (MEE-neez) conquered Lower Egypt and united the two into one kingdom. He founded his capital city at Memphis, located near modern Cairo (KIE-roe). This unification marked the beginning of the Old Kingdom, a time in which Egypt remained united politically and Egyptian civilization reached its height. Power passed smoothly from one member of the Menes family to another. The clear explanation to why the Old Kingdom was able to develop this period of political stability is found in all the advantages offered by its geography. Especially the gifts of the Nile river. This palette is believed to depict Pharaoh Menes conquering the Pharaoh of Lower Egypt. A Blessed Environment The Nile River has two main sources: the high lands of Ethiopia, and Lake Victoria, in present-day Uganda. It flows northward for about 4,200 miles (6,700 kilometers) until it reaches the Mediterranean Sea. In its course, the river cuts through the Nile Valley which is about 12 miles wide (19 kilometers) and 880 miles (1,400 kilometers) long. The valley is bordered on both sides by high rock walls, beyond which is desert. Both the rock walls and the desert form a natural barrier that helped protect the people of the Nile Valley from raids by desert nomads. This helped protect the kingdom and left it in peace. As it nears the Mediterranean, the Nile River branches into many smaller rivers and flows through the Nile Delta. This is a broad, fan-shaped plain of fertile soil deposited by the river as it empties into the sea. Owing to the richness of the soil ,the Nile Delta has been heavily populated throughout Egypt’s history. To the east of the delta lies the Isthmus of Suez, bordered on the north by the Mediterranean Sea and on the south by the Red Sea. This narrow neck of land connects the The Nile River is one of the few rivers in the world that flows north. Thus Lower Egypt was downriver and in the north, whereas Upper Egypt was up river in the South northeastern part of Africa with Asia. The Isthmus of Suez is the only break in the natural barriers formed by the rock walls of the Nile Valley. It linked Egypt with the rest of the ancient Middle East and provided a route to and from Egypt for trade. But, since Egypt’s neighbors during the Old Kingdom were relatively small and undeveloped, it left them safe from invasion. The Greek historian Herodotus called Egypt the “gift of the Nile” because when the river floods each summer, it deposits a layer of rich soil on the land. From very early times, Egyptian farmers relied heavily on the yearly floods. After harvesting their crops in March and April, the farmers waited for the great river to overflow its banks and deposit the rich black soil carried by its waters. After that, they planted their next crop. Farmers were able to plant as many as three crops a year in this very fertile soil. Each new generation was able to reuse the same land because the Nile renewed the soil year after year. Egyptian farmers used complex irrigation much like in Mesopotamia. Dikes were built all around a field, and canals were used to lead the water from the Nile. Then the dikes were opened in such a way that the water irrigated one field at a time. Thus, a wide variety of crops were able to be grown in the fertile soil of the delta and on the farmlands bordering the Nile River. There were pastures for cattle, goats, and sheep. Fish were plentiful, and birds were hunted in the tall reeds that grew along the river banks. This kept Egypt well fed with less labor, freeing up people for other tasks. In fact, the Egyptians had more of a problem in finding work for their growing population. Beyond food, the Nile valley provided other resources. The reeds that grew along the river provided material for baskets, mats, sandals, and boats. Most important of all, the Egyptians invented a method of splitting and pressing the river reeds together to make a substance similar to present-day writing paper. The plant used to make this paper like material was called papyrus (puh PIE-rus). Papyrus also had many other uses. Its roots could be used as a source for fuel. The fleshy tissue in the stem of the papyrus could be used as food. The fine river mud was used for making bricks and day pots, jars, and other containers. Blocks of limestone and sandstone, cut from the rock walls bordering the Nile, were used in building the great pyramids and temples of ancient Egypt. Copper was mined in the eastern desert and the Sinai Peninsula, and gold came from the nearby desert and from Nubia, a region to the south. The Nile River gave the Egyptians another advantage as well. The northward flow of the river carried boats toward the Mediterranean. On the return trip a ship’s sails could catch the prevailing winds that blow in a southerly direction across Egypt most of the time. River travel took precedence over all other means of transportation in Egypt. It encouraged a lively river trade that helped unify the country’s economy and also fostered political unity: a ruler who could control river transportation could control the country. In this way, Pharaoh’s, like Menes, led a centralized government. Unlike in Sumer, all of Egypt’s cities were united together. Unlike the world of Mesopotamia, the Egyptians were blessed with an ideal environment. Their greatest challenge was in how to keep nature and society working in harmony. To do this, the Old Kingdom established a complex theocracy that they believed would make things work perfectly, forever. Government and Religion in the Old Kingdom As in Sumerian society, religious beliefs formed the basis of authority for the rulers. In Egypt there was no separation of church and state. Egyptian rulers, known as Pharaohs, were religious leaders as well as political leaders. To understand how the Pharaoh ruled we must first understand the role of the gods. Egyptian Gods In ancient Egypt, religion was very complex. Each local area had its own gods and goddesses which would mean the name and duty of a god in one city wasn’t necessarily the same in another city. The leading gods, their name, and what they were responsible for would change depending on where the particular ruler at the time was originally from. For example, Egyptian gods were often seen as Ra, (the sun god), Horus, (god of the sky) and Sobek, (the anthropomorphic creatures, meaning they were god of crocodiles) were all at different times considered to be part human and part animal. the chief god of creation. But, in general, the Egyptian gods played the same role as in other ancient religions. They explained various forces of nature and how mysteries of life worked. In general, Isis was the goddess of fertility and agriculture and her evil brother Seth, the god of the desert. Although Sobek was the crocodile god and god of the Nile, Hapi, was the god of the Nile flood. Three gods that were critical to human life were Horus, the falcon god of the sky, and later in the Old Kingdom, Re (Ray) the sun god. Horus was considered to be the protector of humans, whose job it was to keep the desert from taking over Egypt. Re, as the sun, was also a protector and giver of life. The third important god was Osiris. He was believed to be the king of the dead and he ruled the afterlife. Pharaohs of Egypt identified themselves as descendants, or the living embodiment of Horus. Thus, they were a living god whose job it was to protect all life in Egypt. When the pharaoh died, he would become Osiris, and be responsible for all the souls in the afterlife. The Pharaoh By claiming to be gods, Egypt’s rulers held even greater power over their subjects than Sumerian rulers. As a god, the pharaoh was thought to have special powers that made it possible for him or her to rule Egypt with perfect judgment and complete power. The pharaoh was believed to control not only people, but also the natural world. The Egyptians believed the pharaohs’ powers were responsible for the flooding of the Nile. Fortunately for the pharaohs, the flooding of the Nile followed a regular pattern and was therefore a source of more praise than blame for the pharaohs. As the descendant of the gods, a pharaoh was the supreme ruler of all Egypt and the judge of all the people. Egyptians believed that the law, which was based on custom, encompassed the will of the gods. Despite their position as gods, even pharaohs were considered to be subject to the law. They were also expected to prepare themselves to be rulers and to provide for the public welfare. A pharaoh’s heir had to study about the needs of Egypt and the management of irrigation, mining, and construction. A new pharaoh was expected to ascend the throne ready to rule and to direct the economy. The pharaoh owned all the land in Egypt and received taxes on goods and services from the farmers. Pharaohs allowed the people to use the land, but they always maintained the right to take away any part of the land they wished. Pharaohs also ordered mining and trading expeditions that brought more wealth to the kingdom. During the Old Kingdom, the relative wealth of Egypt and its natural barriers to invasion promoted a government based on peace. Egypt had no standing army or professional military corps. Government was based on cooperation rather than force. The pharaoh administered control over Egypt through civil officials. The most important official was the vizier (vuh-ZIR), or prime minister. Viziers emerged in Egyptian society by the beginning of the Old Kingdom and gradually came to run almost every part of Egyptian government when the pharaoh’s power declined in later dynasties. Despite this, it was always believed that the vizier spoke “with the voice of the pharaoh”. Egyptian art always portrayed the Pharaoh as a larger than life, idealized person. He was after all a god on earth. Among his many duties, the vizier acted as judge, trying cases and hearing appeals. He also appointed judges in the local courts, and controlled irrigation and agriculture. He was responsible for collecting taxes, and entertained important visitors from other lands. It was the vizier’s duty to keep the roads and buildings in good repair. Other important government officials included the high priest, the chief architect, the royal treasurer, the royal official who looked after the pharaoh’s household, and the teachers of the royal children. So, the pharaoh had complete control over the people and government of Egypt because the people believed that as a living god, he was responsible for continued good blessings of this earth. The Nile flood, the relative resources, peace with ones neighbors were all due to the existence of the pharaoh. But if the pharaoh was a god, then why did they die? To understand just how powerful the pharaoh was, we also must understand their belief in the afterlife. Egyptian Beliefs About Death In the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians believed in reincarnation, or that the person would live again. Unlike other religions that believe in reincarnation, the person would live forever not in this kingdom, but in a kingdom of the dead that was located west of the Nile river where the sun set each day. This reincarnation could only happen when the soul (the Ka) and the body (the Ha) were reunited in the afterworld. If the Ha, or body, was lost; then the Ka would be lost for all time. Egyptians believed the person consisted of two part, the body, or Ha and the soul or Ka. The Ka is seen in this tomb painting as a white stone which the Ba Bird would fly back and forth from this world to the afterworld. Got it? In the Old Kingdom, the death of a pharaoh meant that the soul of Horus was departing this world to become the new Osiris in the land of the dead. He would then invite those people he had lived with to join him in the afterlife. In this way, the people depended on the pharaoh not only for this life, but the afterlife as well. You had to serve the pharaoh well here in order to be allowed into the afterlife. In order to make sure the body of the pharaoh was reunited with its soul, the Egyptians practiced two new forms of technology; mummification and pyramids. Mummification: Mummification, or embalming, is the process of preserving a human body by drying it out. When moisture is removed from the body, it will not rot. Egyptians learned about mummification naturally. The dry environment and high salt content of the desert sands were ideal conditions for natural mummification. Egyptians probably started to develop these beliefs when Neolithic Egyptians discovered that the bodies of their deceased did not decay when buried. The mummification process in the Old Kingdom was not the highly developed process that it would become in the Middle Kingdom. Commoners were most likely just placed in graves and let nature do its best. We aren’t sure of the process that pharaohs went through, because whatever it was, it didn’t seem to work. We have no mummies of Old Kingdom pharaohs. In fact, only seven mummies are known from the Old Kingdom and they are all from common graves. The Pyramids Once the pharaoh’s body had been preserved by some method of mummification, it was then necessary to protect it so the body and soul would be reborn in the afterlife and then bring the other people of Egypt with them. Egyptians built pyramids to provide a fitting burial place for their pharaoh god-kings because they believed the pharaohs held the key to the afterlife for all. Pyramids reflected the Egyptians’ strong conviction in life after death. They also reflected the ability of the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom to marshal the resources of Egypt to provide the labor and materials for these huge monuments. The first pyramid, which was built for the pharaoh Zoser (ZOE-sur), was begun about 2600 B.C. The pyramid was made in steps of small, square stones and was surrounded by beautiful white limestone temples and other buildings used for worshiping the dead pharaoh. The building of a pyramid was a huge public- works project taking many years to complete. Thousands of Egyptians worked under the direction of architects and overseers during the seasons when fewer workers were needed on the farms. The pyramids were not built by slaves! They were built by people who were willingly serving the pharaoh for their entrance to the afterlife. In return, the pharaoh was able to provide work, food and resources to all the people of Egypt in times when there was not work. In all there were 138 pyramids built that we have discovered. All were built on the west side of Nile which was considered the land of the dead. The greatest of the pyramids in the Giza complex is the pyramid of Cheops. Cheops (KEE-ops), known to us as Khufu, required the labor of 100,000 people over a twenty-year period. The structure, which contains over two million limestone blocks fitted together with almost perfect precision without using mortar or cement, rose to a height of 480 feet (146 meters). Left: The first pyramid, Zoser’s Step Pyramid; Middle: The Great Pyramids at the Giza Complex; Right: The pyramid of Amenemhet I, in all there are 138 identified pyramids in Egypt. Not all remain in as good condition as others. Decline of the Old Kingdom In time the pharaohs were no longer able to control all of Egypt. At the height of the Old Kingdom, a few officials ruled Egypt. Many were related to the pharaoh and owed their well-being to the pharaoh’s generosity. As the number of officials increased, some left the pharaoh’s household. Many official positions became hereditary, and people of ambition and talent were cut off from the opportunity to serve the kingdom. Less able administrators inherited positions of power and influence and did as they pleased while the Pharaoh spend all of his time preparing his pyramid. At the same time, the Egyptian economy was being drained by taxation to support the ceremonies held at the pharaohs’ temples. Between 2200 B.C. and 2050 B.C., a great struggle for power took place in Egypt as the influence of the pharaoh waned. Priests and local nobles fought among themselves for leadership, and Egypt became a divided country. As the central government collapsed, local nobles usually became the real rulers. The decentralization of power had an impact on other phases of Egyptian life as well. The quality of art produced by artisans of the pharaoh’s household declined, and the building of great monuments was sharply curtailed. The Middle Kingdom Around 2130 B.C., a prince from the city of Thebes (THEEBZ), Amenemhet I (ah-meh-NEMhet), began to restore the power of the pharaoh and the local rulers and to reunite the country. Thus began the period known as the Middle Kingdom, which lasted from 2050 B.C. to 1792 B.C. The Middle Kingdom was a time of peace and prosperity. Amenemhet began a process where Egyptians would spend their time and energy expanding trade with other nations instead of spending all their resources on pyramids for the pharaoh only. The challenge of the Middle Kingdom would be how to become wealthier and share the success among all the people. Changes to Government: Beginning with Amenemhet I, and during the next two dynasties, the role of the pharaoh changed. As before, pharaohs were considered to be gods, but they no longer had absolute power. Now they had to share their power and wealth with the nobles and priests. The people no longer believed that a person could achieve a place in the afterlife only through association with the pharaoh. In addition, the people no longer feared the pharaohs, but instead considered them to be their protectors. The pharaohs themselves seemed more concerned with the welfare of the people than they had previously. Tales of pharaohs trying to ensure justice and good government for the people appeared in Egyptian literature of the time. A Focus on Trade The Egyptians traded with many parts of the ancient world. Instead of building pyramids, Pharaohs put people to work building ships, and sent explorers to find make contact with neighboring civilizations. Their ships brought timber from Phoenicia, finely worked objects from Sumer, and carved ivories and weapons from Syria. They also brought olive oil, honey, copper, wine, tin, lead, and iron from other countries of the ancient Middle East. Caravans brought back ebony, ivory, animal skins, and gold, as well as slaves, from the lands south of Egypt. There is some evidence that Egyptian ships sailed as far as the Aegean Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the coast of India to trade. Egyptian glass blowers And of course, Egypt had to have things to trade in exchange. So the pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom encouraged new industry. Starting here, we have evidence to suggest that Egyptians had actual factories that specialized in making trade goods like textiles, pottery and glass. Glassmaking may have occurred accidentally due to the over firing of faience (fay-AHNS) ware, a fine, glazed pottery with partially fused minerals in it. During the Middle Kingdom Egyptians made glass objects such as statuettes and jewelry. Most trade was conducted by barter, or the exchange of one type of thing, such as timber, for another of equal value, such as ivory. This is particularly true of trade done by peasants and poor farmers. In some cases, rings of copper and gold were used as currency in larger dealings by merchants and traders. Historians believe that Egyptian trade was well organized. From early times Egyptians developed elementary methods of accounting and bookkeeping. Egyptians also originated deeds, wills, and written contracts. A few commercial records on papyrus have been found. The Egyptian records, however, are not as complete as the cuneiform tablets historians have analyzed from other ancient Middle Eastern peoples. New Social Classes With this new found wealth, new social classes began to emerge. The most important figure in Egyptian society was still, of course, the pharaoh. But now, sharing, in the pharaoh’s wealth and prestige were the officials who helped administer Egypt, and the priests who advised the pharaohs and carried out ceremonies in the temples. And now, due to new trade, merchants and artisans became important members of Egyptian society. During the Middle Kingdom they even revolted against the priests and nobles in order to get more rights. The bulk of the Egyptian population, however were peasant farmers who lived in rural areas along the banks of the Nile. The cost of supporting the royal household and building projects fell mainly on their shoulders. It is probable that farmers were assessed one-fifth or more of their crop production each year. There was a vast gulf between the standard of living of the nobles and that of the poor. The life of the peasant was hard and changed little from century to century. However, it is important to note that Egypt still did not practice slavery throughout the Middle Kingdom. Changes in Religion. Since religion and government still went hand in hand, there were changes to both religious beliefs and practices. One of the most important changes of this period was in the role of priests. They were given more religious duties and acted as intermediaries between the people and the officials of the royal househo1d. Gradually the position of priest was passed down from father to son, and they formed a large wealthy class whose power rivaled that of the pharaohs. The Valley of the Kings. The door and wall structures are present day additions to keep the tomb entrances from caving in. In Ancient Egypt the entrances would have been completely hidden. Another significant change in practice was a decline in the building of stone pyramids and an increase in construction of rock cut chamber tombs, which were less expensive and less time-consuming to build. In this way, the pharaoh was able to spend more time administering the government. Pyramids had never really served their purpose in protecting the pharaohs’ bodies anyways. Even before the Middle Kingdom began it is believed that most of the pyramids had been raided and the bodies destroyed. Instead, pharaohs began to hide their remains in secret tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Although great care was taken to decorate the inside of the tomb, the entrance and outside of the tomb were hidden. In the long term, this didn’t completely work either, because there were thousands of people involved in the burial process who knew the “secret” location. Pharaohs of the New Kingdom would continue the tradition of building their tombs in the Valley of the Kings, but gave up trying to hide them and instead built elaborate entrances. The changes in social classes was reflected in a change in the belief about death. Whereas in the Old Kingdom, people believed that they could participate in an afterlife through their associations with the pharaoh. But, since classes in the Middle Kingdom were considered more equal, it was now believed that all people would be thought of as equals in the next world. The pharaoh no longer decided if you went to the afterlife, but was here to help all people gain access to the next life. The process of mummification was now becoming more complex in an attempt to ensure a better afterlife. The wealthier you were, then the more of the complicated process you could afford. The most expensive process of mummification took about seventy days. The brain was drawn out of the skull through the nose. The heart was left in the body because it was thought to be the center of a person’s will and intelligence. Other organs were removed and preserved in jars that were placed in the tomb near the mummy. Dehydrating agents were put inside the stomach area to keep the body from decaying. Finally, the body was very carefully wrapped in hundreds of strips of linen. The mummy was then placed in a tomb along with food and drink to nourish him or her in the afterlife. Despite these careful preparations, most mummified bodies were damaged or destroyed by vandals or thieves. The bodies of poor people, conversely, were buried in the hot, dry desert sand, and often were better preserved. The Egyptian mummifiers at work. Pharaoh Ramses II as he looks today, even though he died 3200 years ago. The Egyptians even mummified animals like this baboon so there would be a variety of animals present in the afterlife. . The Decline of the Middle Kingdom: Not all of these changes turned out to be positive in the long run. The strengthening of the priests’ influence and weakening of the pharaoh’s power changed the character of Egyptian government. Authority became decentralized. The kingdom became divided when local nobles refused to submit to the pharaoh’s authority. Thus political unrest disunited Egypt’s unity once again. Provinces and cities stopped working together just at the time Egypt was about to face their greatest threat. Egyptians were about to find out that wealth attracts new neighbors, and not all neighbors are nice. The Hyksos Invade Egypt Although little is known about the last pharaohs of Middle Kingdom, the existence of natural barriers may have lulled them into a false sense of security. Frontier defenses to the north became lax, due in part to the Egyptians’ belief in their own superiority. Egyptians thought that their country was the only one protected by the gods and, according to this way of thinking, all other peoples were subject to them. However, not all other peoples accepted such a notion, and some made plans to conquer Egypt. Among the invaders poised beyond Egypt’s borders and ready to take advantage of any sign of weakness were the Hyksos (HIK-soes), which is what the ancient Egyptians called the Asians. The Hyksos invasion was part of a wave of invasions, including those of the Hittites and Kassites in Mesopotamia, that disrupted civilization in the Middle East. The Hyksos were a conquering people who had entered Canaan about twenty years prior to entering Egypt. By 1730 B.C. they had traveled over the Isthmus of Suez and through the Nile Delta. The Hyksos quickly defeated the Egyptians and established their capital at Avaris, in the northern delta of Egypt. The success of the Hyksos was linked to their use of lightweight chariots pulled by fast horses. This gave the Hyksos the ability to maneuver easily and strike swiftly. The Hyksos also introduced Egypt to bronze weaponry. Prior to this, the Egyptian army was outfitted with soft copper weapons. The Hyksos ruled Egypt for over 100 years, and even established their own dynasties. While the Egyptians hated these foreigners and resisted many of their ways, the Hyksos did bring some prosperity to the country. They repaired the old roads or built new ones to connect northern Egypt with routes to Asia. Hyksos forts and well-armed garrisons provided protection for travelers and traders who used those roads. Gradually, however, the Hyksos allowed some Egyptian princes, such as those at Thebes, to gain local independence. Once those princes had effectively learned to use the Hyksos’ weapons and basic military techniques, they waged a patriotic war against the Hyksos and by 1570 B.C. drove them from Egypt. According to ancient Egyptian legend, this rebellion began when a Hyksos pharaoh ordered a Theban prince to “silence the bellowing of the hippopotamuses who were disturbing his sleep.” The Egyptian prince, who had attached great significance to the animals and greatly admired them, refused to obey the Hyksos king’s order. Unfortunately for later scholars, the Egyptians, in the course of winning the war, destroyed most of the records of Hyksos rule. The New Kingdom After the Hyksos were driven out, Egypt entered another period of unity called the New Kingdom, which lasted from about 1570 B.C. to 1090 B.C. During this time a series of strong pharaohs ruled Egypt from the capital city of Thebes who would make sure that the mistakes of the Middle Kingdom would not be repeated. The challenge of the New Kingdom pharaohs was in keeping themselves wealthy and powerful for all eternity. They met this challenge by returning to absolute rule. They stripped the priests and the nobles of some of their power and kept tight control over the government. Then they made sure they would not be invaded again, by becoming the conquerors themselves. The Egyptian Empire After the Hyksos invasion, the Egyptians realized that it was possible for invaders to enter and occupy their land. Pharaohs realized that they had to protect themselves and as the first step in that direction, they formed an army. The Egyptians felt that safety would come only from controlling the surrounding areas, and thereby keeping this territory out of the hands of rival powers. The Egyptian army of the New Kingdom was a professional army and much larger than that of the Middle Kingdom. Modeled on the Hyksos army, it used horses, chariots, and bronze weapons. Just as the Hittites had used the chariot in the creation of their huge empire, the Egyptians used it to expand their territory. The pharaoh had a full-time army, ready to fight at a moment’s notice. Many of the soldiers were former prisoners of war who could gain their freedom by serving in the Egyptian army. With this new and stronger army, the Egyptians conquered the whole area along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean area as far north as the Taurus (TAW-rus) Mountains. They then moved south into the region that is now the Sudan (soo-DAN). As the Egyptians took more and more land, the empire grew rapidly. The pharaohs, however, soon found that it was sometimes easier to conquer a land than to rule it. During the reigns of weak pharaohs, parts of the empire revolted and tried to break away. Only the strongest pharaohs were capable of holding the empire together. Hatshepsut: Among the ablest and most powerful pharaohs of the Egyptian Empire were Hatshepsut (hat-SHEP soot) and her husband, nephew, and stepson, Thutmose III (thoot-MOE-suh). Hatshepsut was a wise and strong pharaoh who ruled jointly with Thutmose III from about 1500 B.C. to 1480 B.C. Hatshepsut was more interested in building a secure and prosperous Egyptian society than in expanding the empire. During Hatshepsut’s rule, Egyptian women enjoyed a better position than had women in most other parts of the ancient world. They had full legal rights and could inherit and sell property without first receiving the consent of their husbands. In addition to completing huge building projects, Hatshepsut restored the temples that had been ruined during the Hyksos occupation. The new paintings and carvings that decorated the walls of these temples highlighted important events that took place during her rule. In this way she was able to put Egyptians to work and demonstrate her greatness to all. She was both greatly loved, and feared. Bust of Hatshepsut Hatshepsut’s Burial Temple Bust of Thutmose III Thutmose III: After Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmose III ruled alone from 1468 B.C. to 1436 B.C. Possibly driven by jealousy, Thutmose destroyed many of the paintings, sculptures, and buildings that Hatshepsut had created during her rule. Thutmose and his followers even destroyed the tombs of her most faithful servants. Thutmose III set out to establish himself quickly as one of Egypt’s most forceful rulers. He extended the borders of the empire as far as the Euphrates River and gained control over Palestine and Syria that lasted into the next century. He also improved the Egyptian army and set up military posts primarily designed to put down revolts throughout the empire. These posts served as a constant reminder of Egyptian power and ensured that the conquered people would pay tribute to the pharaoh. Thutmose held the children of conquered princes as hostages and educated them in Egypt. The children were taught that the pharaohs were powerful enough both to protect conquered peoples and to punish those who tried to revolt. It was hoped that this indoctrination would persuade the children, once they grew up and became rulers of their own lands, not to dare oppose the regime of the pharaoh. Thutmose was a very able ruler. He devoted much time to the ruling of his empire, and personally judged legal cases. He also rebuilt temples with the labor of prisoners of war and decorated the temples with chalices and urns of his own design. Wall paintings from about 1500 B.C. show foreign sailors bringing the products of their lands to exchange for Egyptian goods, indicating that trade with other countries also increased during the rule of Thutmose. The Common People Lose Their Rights The military victories of Thutmose and other pharaohs of the New Kingdom made Egypt rich and powerful. The tribute collected from conquered peoples helped make the pharaohs and the nobles wealthy, but unlike in the Middle Kingdom, those riches were not going to be shared with the common people. Most of the Egyptian people lived in poverty, while the rulers grew rich and corrupt. The freedom of the common people decreased as the pharaohs’ power increased. They had no political rights and depended entirely on the whims of the pharaohs for justice. The whole concept of the rule of the pharaohs had changed from one based on national unity to one based on military strength. If your town wished to rebel, there would be a visit from the new military. And once beaten, you would be a prisoner of war. Prisoners of war were put into a new class of people introduced in the New Kingdom – slaves! Even the common people were not much better off than slaves. As you know, during the Old Kingdom the pharaohs owned all property in Egypt. Until the New Kingdom, the pharaohs had allowed the people to use the land as if it were their own. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom, however, treated large parcels of land as their private property and forced the peasants to work the land for them. Periodically the peasants were forced to work on huge building projects, which caused great discontent among the Egyptian people. Religion in the New Kingdom Because pharaohs in the New Kingdom were most occupied with worldly problems of wealth, power and conquest, there role in the religion changed. They were now no longer seen as gods. People now saw the pharaoh as a mortal being who ran the government and had little impact over their religious needs. Instead, people worshipped various gods through the priests. This change could be seen in new beliefs about access to the afterlife. Now Egyptians believed that after they were buried their spirits would be sent to a great hall where their sins were judged. There they pleaded before forty-two gods for eternal life. The dead had to declare virtue, know the secret names of the gods, and be able to cast magic spells that would drive off dangerous snakes and crocodiles. Spells were necessary to survive the dangers of a journey across a lake of fire, and to keep the dead from forgetting their own names. The Egyptians believed that if a dead person were to forget his or her name, that individual would die again. If the dead surmounted all these trials, they would arrive at a place called the “Field of Rushes,” where their lives would remain pleasant forever. These Egyptian beliefs about death arid eternal life, developed over thousands of years, were finally recorded about 1500 B.C. in the Book of the Dead. Divisions in the social classes was also reflected in this new change. The wealthier you were and the more offerings you gave to priests, then the more you could purchase the knowledge and secrets you would need to pass the tests. Akhenaton Amenhotep IV was a pharaoh who tried to reform Egypt by turning everything on its head. He rejected the greed and power that came with conquest. He had little interest in saving the empire, some of whose subjects were transferring their loyalty to the Hittites. Instead, he wanted to take Egypt back to its own traditions when the pharaoh was seen as the only key to an afterlife. In order to do this, Amenhotep IV under took a reformation of Egyptian religion. During the New Kingdom one of the most important gods was Aton A Pharaoh family portrait. Akhenaton, wife Nefertiti , and their three daughters are seen under the rays of the sun god , Aton. For the first time (AH-ton), the sun god. Around 1375 in Egyptian art, the Pharaoh was seen as human and emotional. B.C. Amenhotep IV elevated the ancient cult of the sun god to a position approaching monotheism. His premise was that Aton was the only true god—not just the most important. To demonstrate his conviction, Amenhotep changed his own name to Akhenaton (ak-kehNAH-ton), which means “he who serves the Aton.” Akhenaton believed he was the son of Aton and, as such, allowed the god to be worshiped only through himself—not through the priests. Therefore, the priests’ importance in society diminished, and the wealth they received in the form of gifts went to Akhenaton. The priests of the older religion were angered by Akhenaton’s power over the Egyptian people. To make matters worse, Akhenaton placed his followers in high positions that previously had been held by priests. Also, the wealth that formerly went both to the priests of Amon and for building temples to the former gods went instead to the pharaoh’s new temples for Aton. In honor of Aton, the pharaoh built a new capital city named Armana. Here Akhenaton set about changing the whole culture of Egypt. Instead of focusing on war, conquest and building projects, he set about creating a revival in art. There scholars have discovered pictures of the pharaoh, his wife, Queen Nefertiti (neh-fer-TEE-tee), and their children. In contrast to the traditional, static representation of pharaohs in earlier art, the royal family here is depicted in various aspects of everyday life, and -their facial expressions reveal feelings and emotions. This is the only era in Egyptian art where you would find artists painting landscapes. Thus, while Akhenaton and Queen Nefertiti were focusing their attention on founding a new religion and culture, the Egyptian Empire continued to decline. The Egyptian common people were unhappy about the pharaoh’s new religion because it offered them little hope of a life in the next world. Foreign princes were challenging the pharaoh’s strength and trying to gain control. Rebellions against Egyptian rule had already succeeded in Canaan, and it seemed as if the empire was on the brink of collapse. Akhenaton’s death, and in fact whole life, remains a mystery because when he died most of his records were destroyed. Tutankhamun Succeeds Akhenaton The priests of Amon and the other gods maintained some control over the people by continually stirring up discontent over the new religion. In 1361 B.C. the young prince Tutankhamun (too-tahngKAHM-un) succeeded Akhenaton as pharaoh at the age of 9. Pressured by the priests, he restored the old Egyptian religion and returned the capital to Thebes. However, Tutankhamun was unable to stop Egypt’s decline and the empire continued to fall into disorder. The situation improved somewhat under the direction of the army general who succeeded Tutankhamun. What followed, however, was the final stages of the Egyptian Empire. The Decline of the New Kingdom The most famous pharaoh of this kingdom was Ramses II (RAM-seez), who ruled from 1279 B.C. to 1212 B.C. Known as “Ramses the Great” he ruled for 67 years and tried to return Egypt to its former glory. He managed to collect enough taxes to construct huge buildings and also built a new capital at Tanis (TAY-nus), in the Nile Delta. This city was called Ramses. One of Ramses II’s battles against the Hittites concluded with the first recorded peace treaty in history. This battle was followed by years of peace, even though nomadic tribes called Sea Peoples continued to challenge Egypt’s rule in Canaan. Ramses II was the last pharaoh to win a major victory over Egypt’s rivals. After his reign, Egypt was no longer able to fight off invaders. Disorder spread rapidly, and Egypt was conquered repeatedly. Invaders, from Libya to the west, controlled the government for a while. These were followed by Ethiopians who invaded Egypt from the south, and the Assyrians who approached from the northeast in 670 B.C. Although the latter conquered the entire country, they were defeated by the Persians around 525 B.C. At this point Egypt’s history as an independent state in the ancient world ended. The Persians ruled Egypt until they, in turn, were defeated by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. It was not until the twentieth century, after falling under the domination of the Romans, Turks, French, and British, that Egypt again became independent. Art and Technology From simple beginnings as a group of agricultural villages, Egyptian society reached a high level of artistic and technological achievement. Egyptian Writing Many visitors to Egypt are struck with the beauty of ancient inscriptions found on walls and tombs. This form of writing is called hieroglyphics (hie ur-uh-GLIF-ilcs), a name that comes from the Greek word meaning “sacred carving,” and dates back to about 3000 B.C. Hieroglyphics were composed of more than 600 signs, which were carved into stone monuments. They were used mainly by priests for religious purposes. The Egyptians did not develop a true alphabet as the Phoenicians later did, but they gradually made hieroglyphic writing more simple. One of these simpler writing systems was a type of handwriting called hieratic (hie-uh-RAT-ik) While hieroglyphics were carved in stone, hieratic writing was written on papyrus with a brush dipped in ink. Much of our present knowledge about Egypt is based on the deciphering of hieroglyphics, in the late eighteenth century a stone was discovered near the mouth of the Nile River. Named for the city near where it was found, the Rosetta stone contained three different types of writing: Greek, which was known, hieroglyphics and a later form of Egyptian writing, which were not known. The stone is inscribed with a decree honoring a king’s restoration of a temple. A French scholar, Jean François Champollion, used the Greek to interpret the other two writings, and published his findings in 1822. Scribes The tremendous amount of Egyptian writing that even today remains intact was the work of scribes, or official writers. Scribes, who were among the most important members of Egyptian society, attended a special school for twelve years. Anyone who studied at this school learned to read and write and was taught the literature and history of Egypt. Scribes also had to know mathematics, bookkeeping, mechanics, surveying, and law. They wrote their records on a roll of papyrus which had fifty times the writing surface of a cuneiform clay tablet. The convenience of writing on papyrus, which could be carried easily, helped spread Egyptian writing to Phoenicia. It later led to the development of the Phoenician alphabet. Egyptian Architecture Surrounded as they were by cliffs, Egyptians of the Old Kingdom made important advances in building with stone. To build temples, palaces, and pyramids, they learned to move huge blocks of stone weighing several tons from one place to another. They cut the stones into the proper shapes with copper saws and then fitted them tightly into place. The Egyptians used a special unit of measure called the royal cubit (KYOO-but), which measured about 21 inches (53 centimeters), or about the length of an Egyptian’s arm from fingertips to elbow. They also used the width of a hand (without the thumb) and the width of a single finger as units of measure. With this simple measuring system, the Egyptians were able to build pyramids having bases the size of eleven football fields! As the Egyptians became more skilled, they built other kinds of monuments. Obelisks (AHB uhlisks), or tall, pointed stone columns shaped like huge needles, were erected for Thutmose III, who began his rule in 1480 B.C., during the New Kingdom. Originally built at Heliopolis (hee-lee AHP-uh-lus), they were later removed and now stand in Istanbul, London, New York, and Rome. Egyptian Art Like the pyramids, Egyptian art was also a reflection of Egyptian culture. Much of it appeared in tombs. During the Old Kingdom, skilled artisans and artists worked with fine materials and deliberate care. Pictures on the walls of tombs displayed a colorful view of life in Egypt. They were painted to provide the dead with reminders of their life on earth. Inscriptions and drawings on the walls of officials’ tombs depicted their service to the ruler. A king might be shown defeating his enemies. Farmers were shown working in their fields. Sculpture was a highly developed art form. The face on the statue was realistic since food and drink were provided for the dead. Statues of the dead were thought to contain some part of the spirit of the deceased. Therefore, the body appeared imposing and static to show timelessness. Temples, such as the one at Karnak (KAHR nak), were decorated with sculptured stone sphinxes (SFINGKS-us). A sphinx is a figure having the head of a human being, ram, or hawk, and the body of a lion. One of the best known Egyptian sphinxes is the one found at Giza (GEE-zuh), which has the head of a man and the body of a lion. Other artwork included beautifully worked small figures of people and animals in copper, bronze, stone, or coal. Egyptian Science The Egyptians were experts in astronomy and geometry. They developed an accurate calendar so that they could predict the flooding of the Nile River. They also measured the angle of the sun’s rays at various times in order to arrange the construction of the temples so that the rays of the sun would fall on specific important places during special rituals. The Egyptians based the length of their year, 365 days, on the time that passed between the appearances of the star Sirius (SIR-ee-us), or the Dog Star. The 365 days were then divided into twelve months of thirty days each. At the end of each year, the five days remaining were observed as holidays. As you know, the ancient Egyptians numbered the years by the rule of the pharaohs. For example, they spoke of an event as occurring in the tenth year of the rule of Hatshepsut. Using this system of dating, historians have been able to trace Egyptian history back to about 2700 B.C. Egyptian geometry developed for very practical reasons. In a land where the borders of fields might be wiped out by the yearly floods, it was necessary to have exact measurements in order to restore these borders. Geometry was also used to lay out the system of dikes and canals that watered the fields. The pyramids and other great monuments of the Old Kingdom were planned Egyptian fraction symbols were components of the Eye of and built according to complex geometrical Horus. Which when drawn whole was also the symbol for 1. formulas. In contrast to their extensive knowledge of geometry, the Egyptians had a simple numbering system. Numbers were written using signs for ones, tens, hundreds, thousands, and so forth, up to one million. For example, the number 22 would be written 10 + 10 + 1 + 1. At least twenty-seven separate signs were needed to write 999. The Egyptians multiplied by doubling numbers until they reached the multiple they were looking for. They used the same process in reverse when dividing numbers. Fractions were used, but no fraction could be written unless it contained the number one as the numerator. Thus the fraction 3/4 would be written 1/2 + 1/4. Although this system had limited use, the Egyptians were able to use it to solve most of their practical problems. Egyptian Medicine Medical writings on papyrus provide much information about Egyptian medicine. The writings cite important cases that were treated and also tell how a patient was examined, what treatment was prescribed, and how the doctor thought the case would develop. Sometimes possible causes of a disease were listed. Drawings indicate that doctors knew a great deal about human anatomy, and it is believed that they gained this knowledge while preparing bodies for burial. Egyptian medicine was valued throughout the ancient world. Egyptian doctors were sent to distant lands to treat rulers and nobles, and most of the large temples had medical libraries and medical schools for training doctors. Foreign doctors often described the drugs and methods of treating disease they learned while studying in the Egyptian temple schools. Egyptian Agriculture and Industry The first people who lived in the Nile Valley caught fish and game and gathered wild fruits and vegetables. Later, barley and wheat brought into Egypt from lands to the east were grown in the fertile Nile Delta and the Nile Valley. These were the two most important staple crops of ancient Egypt. A staple crop is one that is used widely and continually and, for this reason, is usually grown in large amounts. Staple crops were grown on large estates, and production was increased by using wooden plows and hoes. Once the use of iron was known, farm implements were made of that metal because it was more durable. Another important aspect of Egyptian economic life was manufacturing. As early as 3000 B.C. large numbers of people, generally working alone, were able to specialize in crafts. In later years people began to work in groups in factories.