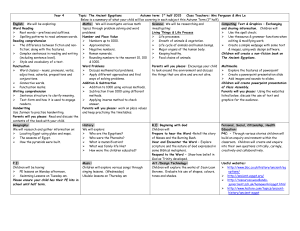

Daily Life in Ramesside Egypt

advertisement

Tully Smyth Page 1 of 6 Daily Life in Ramesside Egypt (l) Explain, using evidence, the daily life of Egyptian nobles (e.g. occupation, housing, furniture, food, clothing and leisure. There were three distinct ‘hierarchal classes’ in Egypt – the pharaoh and nobility at the top of the pyramid, followed by priests, scribes, warriors, and skilled workers. The nobles were the highest social rank beneath the Pharaoh and the Royal family, and included members of the court, close associates of the Royal family, officials and bureaucrats. At the bottom, supporting it all, was a large body of unskilled agricultural labourers. We as historians are bombarded with information on the top level, and these are therefore the strata I have focused on. A day in the life of a noble of the time would have been mainly taken up by hunting, and various leisure activities due to the fact that they had the time and money to do what ever they pleased and lived a carefree life. However, although evidence from ancient Egypt, and more specifically the Ramesside period, comes mainly from the tombs and funerary goods, the Egyptian ambition to re-create the conditions of their daily existence in the afterlife has resulted in the preservation both of tomb scenes, showing many facets of their lives, and of objects such as furniture, clothing, cosmetics and jewellery. Therefore through evidence such as temples, tombs, papyri and octrica, we are able to also draw conclusions on other daily life areas, such as occupations, housing, furniture, food and clothing. A working day for Ramesside Egyptians took many forms. Agriculture was the basis of the Egyptian economy and consequently, the daily work of the vast majority of the Egyptians was linked with farming. However, a specialized bureaucracy monitored or controlled much of Egypt’s economy. Although they didn’t tell the farmers what to grow, they’re role was to re-measured and reassigned the land after every inundation - based on past assignments, assessed the expected crops, collected part of the produce as taxes, stored and redistributed it. Bureaucrats were also in charge of public works which were Tully Smyth Page 2 of 6 mostly religious in character and involved at times tens of thousands of workers and administrators. The period of inundation was a time where very little could be done agriculturally, and this was the time when leisure became a way of life not only for the farmers, but also for nobles. Gardner explains that ‘music, songs, dancing, buffoonery, feats of agility, or games of chance’ were a large part of Egyptian leisure. The most common leisure activity for the nobility seems to be drinking parties, accompanied by hired musicians, dancers, acrobats and singers. Other favorite pastimes included board games like Hounds & Jackals and what Gardner thought of as ‘draughts’, what we now know as senet. Senet was a game with unclear rules, where figures were moved around a board against an opponent. The tomb of Ramesses III contains such figures, and the Book of the Dead records royal scribe Ani playing the game. The modern locality of Beni Hassan records physical leisure: weightlifting bags of sand, wrestling, boatfighting with poles, athletics, and my favourite, beating each other with sticks. Discus throwing is shown in a 19th Dynasty pharaonic tomb. Fishing and Fowling was also a popular leisure activity and is depicted in tomb scenes1 side-by-side with the noble as the central character. He is shown on a small papyrus boat in the marshes which are alive with wildlife, and two ‘Tilapia’ fish are shown being caught and put on a spearlike mechanism while wild fowl are killed with a throwing stick. Egyptians were renowned throughout the ancient world for their culinary expertise, and the type of food they ate was fairly specific. Animals were a scarce commodity, as the agricultural land Egypt had was taken up by growing grains and vegetables. The matter of class comes into what Egyptians would have eaten, but we know from Plutarch that ‘no Egyptian eats mutton’. Nobility tomb scenes show that the richer classes had a penchant for that most charming of animal – goat, as well as ibex, oryx, and gazelle. Wild geese were eaten, as well as ducks, snipe, and quails. And the Nile again treated the Egyptians with an abundance of edible fish, although it didn’t keep very well in the heat. Agriculture again shows its importance, as Pliny tells us that the Nile valley ‘surpassed 1 Fowling in the marshes: fragment of wall painting from the tomb of Nebamun (no. 10) Tully Smyth Page 3 of 6 every other country in the abundance and spontaneous growth’ of vegetables. Ramses III allotted the Amun-Re temple figs, grapes, dom-palm fruit and pomegranates: ‘Mehiwet: cakes 3100, Khitana-fruit: heket 310, Khitana-fruit: bundles 6200.’2 Some of these fruit were only eaten fresh, but many were dried in order to preserve them. Jars of raisins were allotted by the thousands to the Nile god temple by Ramses III, as were dried dates. However the most commonly eaten foods in Egypt were onions (which were also used as currency), garlic, lentils, and a flatbread made from barley, sorghum, or wheat flour. However, it is evident that the abundance of food significantly changed during the 19th and 20th dynasties in comparison to earlier dynasties. During the Rammeside period, surplus became low, with food becoming less plentiful. One Egyptian woman called it ‘the year of the hyaenas, when everyone was short of food.’3 However continuity proved that Egyptians liked good eating, as depicted by the great Harris papyrus, which lists all the offerings made by Ramesses III to the gods; records the presentation of foodstuffs at least as often as of precious metals, garments and perfumes. Egyptian clothing styles did not change much throughout ancient times. Clothes were usually made of linens ranging from coarse to fine texture. Small amounts of silk were also traded to the eastern Mediterranean, as a few strands of material, which analysis proved to be hydrolysed Chinese silk, were found in the hair of a 21st dynasty female which was discovered in the workers' cemetery of Deir el Medina. During the Ramesside period, noblemen would sometimes wear a long robe over his kilt, while the women wore long pleated dresses with a shawl. Interestingly, however, in the course of the New Kingdom and in particular during the Ramesside period, feminine fashion became ever more varied and sophisticated. This has been put down to influences from areas of the Near East occupied by Egypt at that time. White remained the most popular colour, only occasionally varied with pastel shades, but dresses were now made of two pieces or more. Some kings and queens wore decorative ceremonial clothing with feathers and sequins. During the New Kingdom, and more particularly under the Ramessids, sandals of plaited papyrus, of leather and even occasionally of gold (for the nobles) were in more general 2 3 James Henry Breasted Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four Theban woman called Arynofer. Tully Smyth Page 4 of 6 use, and according to the Harris papyrus Ramses III gave to the Amen priests, ‘Papyrus sandals: 15110’4 However it is also interesting to note that medical papyri from that time period, indicate that food complaints were also very common during this time. Clothing styles were chosen for comfort, rather than aesthetic purposes, because of the hot, dry climate of Egypt. Using the skeletons and remaining framework of houses left behind at Deir el-Medina, we are able to draw reliable conclusions as to the format of housing during the Ramessie period. Wealthy Egyptian people had spacious estates with comfortable houses. We can form some idea of the eternal appearance of houses belonging to noble’s, the wealthy etc, from the reliefs which Apouy and Neferhotep had carved in their tombs. However, if we wish to learn about the internal arrangements, we must visit the excavations at el Amarna. The houses had high ceilings with pillars, barred windows, tiled floors, painted walls, and stair cases leading up to the flat roofs where one could overlook the estate. There would be pools and gardens, servant's quarters, wells, granaries, stables, and a small shrine for worship. The wealthy lived in the countryside or on the outskirts of a town. Made from bricks of sun dried mud, called adobe, because wood was scarce, a nobleman's home was divided into three areas: a reception area, a hall, and the private quarters. The windows and doors on the house were covered with mats to keep out the flies, dust, and heat. The ancient Egyptians, even the wealthy ones, had a very limited assortment of furniture. A low, square stool, the corners of which flared upwards and on top was placed a leather seat or cushion, was the most common type of furnishing. Chairs were rare and they only belonged to the very wealthy. Small tables were made of wood or wicker and had three to four legs. Beds were made of a woven mat placed on wooden framework standing on animal-shaped legs. At one end was a footboard and at the other was a headrest made a curved neckpiece set on top of a short pillar on an oblong base. Lamp stands held lamps of simple bowls of pottery containing oil and a wick. Chests were used to store domestic possessions such as linens, clothing, jewellery, and make-up. 4 Breasted Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four Tully Smyth Page 5 of 6 Thanks to the fabulous preservation of ancient sources such as tomb scenes, papyri, octrica and Deir el-Medina in its entirety, we are able to draw conclusions on the way nobles lived during the Ramesside period. Being generally wealthier, they perhaps had more leisure time, more luxurious clothing, housing and food, however were still hard workers. Even during the general decline of the Ramesside period, nobles continued to live wealthy, and it is only because of their ambition of re-create their daily existence in the afterlife, that we are able to understand exactly, the standard of which they lived their lives. Tully Smyth Page 6 of 6 Bibliography: Sources: David, Rosalie Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 1998 Brier, Bob and Hobbs, Hoyt Daily Life of The Ancient Egyptians, Greenwood Press, 1999 Callender, Gae The Eye of Horus- A History of Ancient Egypt, Longman Australia Pty Limited, 1993 Hennessy, D (ed) ‘Studies in Ancient Egypt’, Nelson, Melbourne, 1993 Herodotus ‘The History of Herodotus- Volume II’ Written 440 B.C.E . translated by George Rawlinson Montet, Pierre Everyday Life in Egypt, In the Days of Ramesses the Great, Greenwood Press, 1958 Other Sources: _________________ http://www.sis.gov.eg/pharo/html/front.htm _________________ http://www.carnegiemuseums.org/cmnh/exhibits/egypt/dailylife.htm _________________ http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/prehistory/egypt/dailylife _________________ http://www.terraflex.co.il/ad/egypt/timelines/topics/index.html _________________ http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/