Costume History: Artifact Analysis

advertisement

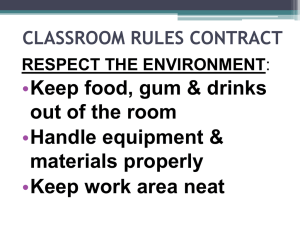

Bright, Megan Saiki FCFA 360 Costume History 4 April 2014 Artifact Analysis: 1850’s Gown By observing, analyzing, and interpreting evidence, I will take an artifact from the Beeman Historical Costume collection and identify the date in which it was worn. To do this, I will first site observations of the dress, then compare them to prevailing styles of surrounding eras, and finally interpret the data. The number on the tag is “C1983.040.001.” The name states “Edna Forest,” and indicates that the garment is from the 1850s. On the bottom left corner of the tag, it reads “UNKNOWN.” The last bit of information on the tag says “1850.1”. The silhouette of the form is typical of the modal type of the day. The dress is floor length, to cover the shoes. Puffy, three-quarter length sleeves give the arm a puffy look at the top, tapering down to the engageants, and finally to the wrist. The shape is form fitting in the upper body, giving an elongated hourglass shape. The dress is made of three fabrics, excluding the engageants. The outer fabric used is an emerald/teal iridescent silk. The iridescent silk makes the fabric look like two different colors depending on the point of view. This fabric started to emerge and become very popular at the time. The fabric feels like it had a finish that made it more water resistant than most silks. The skirt and bodice lining are made from a woven fabric, a cotton or linen. The wrinkling of the fabric indicates a linen, but could also be the effect of 160 years. The inset “bust improver” is made of a different fabric than the lining but is made of the same fabric as the pocket. This fabric is a little darker and a little softer. Two types of sewing occurred in the production of the dress. Perfectly straight, consistent stitching indicates that machine sewing was used for most of the dress, including the side seams and longer lines. Machine sewing also stitched down the gathers, which were probably prepared by hand basting. Hand stitching was done on several parts of the dress. The engageants are lightly hand-sewn to the insides of the sleeves. Another hand-sewn part is the hem. Now I will elaborate on “occurs” or features of the dress. The “bustimprover” is the name of the padding device concealed inside of the dress. It started to become popular in the 1840s, about 10 years prior to the making of this dress. The bust improver, like the modern day bra, was used to enhance the amplitude of the bust. Hooks & eyes are used in the front detailing of the bodice and down the back to close the garment. Boning is used in the front bodice, just below the bust improver. This added structure to the silhouette. Pleats go down the dress below the waistline. Gathers are used in the waistline. One pocket exists in the dress. Interestingly, the pocket is not accessible from the outside. Engageants were hand sewn to the inside of the sleeves. These are made of lace. They add a delicate feature to the dress. The last feature I will mention is space for a hoopskirt. The dressmaker had to consider how much room the hoopskirt needed when deciding the width. Alterations must be taken into account when analyzing the dress. Evidence of alters or repairs are not very noticeable but a few features exist to suggest otherwise. First of all, the hem was quite possibly shortened. The hem is completely hand sewn instead of machine sewn and a bias tape was added. More likely, the owner did not have a sewing machine at this time. Secondly, one single pocket resides on the inside of the dress and is not accessible from the outside of the garment. The pocket was likely added after the making of the dress. Possible functions include daywear, eveningwear, and outerwear. The dress would make a great day dress because the sleeves are not too short and engageants make them even longer. On the other hand, the gown could function as a night dress because of its relatively low neckline. Lastly, the dress would function nicely as an outerwear garment because the fabric is sleek to the touch and would be more water resistant than cotton. The following is a sketch of the garment: The garment is from the 1850’s. Several features make this evident. The pagoda sleeves, use of engageants, space for a crinoline underskirt, and use of iridescent fabric will all be the points of focus when dating the artifact. The first piece of evidence is the pagoda-style sleeve. Pagoda sleeves were a popular shape in this time period. Pagoda sleeves open wide, and were reached the height of their popularity around the 1860’s. This narrows the time span to the middle of the 19th century. The photo below is an example of pagoda sleeves. The next piece of evidence is the use of engageants, or false undersleeves. These were a popular feature after the invention of lace. Europeans were said to have had a “love affair” with lace (Seabastian, 1), using engageants often. The invention of lace dates back as early as the 15th century (1). In the two centuries following, the spread of lace grew rapidly. However, we know that the dress could not have been that old because of the machine stitching. The use of sewing machines in dress-making did not come about until the late 1700s during the first wave of the Industrial Revolution. The earliest patent recorded was that of Charles Weisenthal. However, the patent only describes the needle used, not the rest of the machine. The second earliest patent belongs to Thomas Saint in 1790 (Bellis, 1). He quite possibly did not even build a prototype of this invention, but merely patented the idea. These clues suggest that the artifact had to have been from the 1800s at the earliest. To be more specific, sewing machines started to become more user-friendly and commonplace around the 1840’s, bringing our dress to a later time in the 19th century. The third feature that makes evident the time period is the width of the skirt. Room for a hoop skirt or crinoline indicates that this dress was before the 1900s when silhouettes started to subdue. The silhouette also indicates that the dress must be from after the 1820’s. During the Directoire Period 1790-1820, dresses did not feature extravagant silhouettes for the most part. If they did, the fullness would be in the back, emphasized with the bustle. pre-1820s (left) 1850’s (upper left) 1860’s (upper right) (courtesy of Big Stock Photo) Looking at the image above, our silhouette most accurately matches that of 1850, with the “v” waistline, three-quarter sleeves, pleats, gathers, neckline, and fullness of the dress. The neckline is not a “bertha neckline” or the wide, off-theshoulder neckline. Instead, the dress covers the shoulders and part of the collar bone, dating it to the 1850s. Lastly, we have iridescent silk. Also known as shot silk, this fabric indicates that the dress had to have been sometime in the 19th century when this textile was popular. The making of shot silk dates back to as early as the 5th century. However, shot silk really became popular from the 1830’s onwards, especially in the mid1800s (Cunning, 270). The fabric looks identical to the dress from the photo below (which was sold online with the title “1840’s Iridescent Silk Blue-Green Ball Gown”). Several pieces of evidence above helps us determine the method of construction. Just to review these can be broken down to four parts. One: iridescent silk was a new feature around the mid 19th century. Two: the use of lace indicates the new technology. Three: Machine stitching helps date the dress to after the 1840’s. Finally: the use of a bust-improver also helps date the dress to post-1840. Baclawski, K. The Guide to Historic Costume (1995.) page 53 Baclawski, K. The Guide to Historic Costume (1995.) page 88 photo of the engageants, hand sewn From my point of view, the costume expresses messages of self-expression, fashion forwardness, and elegance. I believe the wearer, Edna Forest, picked the color because it was almost a forest-green. She probably had pride in her family name, and therefore wanted to express this pride. The dress is fashion forward because its use of iridescent silk, low neckline, and other features agree with the modal type of the period. This tells me that the wearer participated in the fashion. Instead of wearing a regular silk or linen, she had a special textile that likely turned heads when she walked into a room. Because there is room for crinoline, she likely participated in that trend as well. The dress is elegant because it can be worn during the day, but could also function very well as an evening dress. The neckline was not too low, but still exposed some skin. Likewise, the sleeves were not too short, but still exposed part of the arm. The item relates to the era because it comments on the use of technology. During the 19th century, lace was very common. This, however, was not something very new. The novelty of the dress lies in the bust-improver, shot silk, and the use of machine sewing. Ultimately this dress is a key transition from the old to the new. The dress gravitates to western fashion, particularly to Europe or North America. Europe was in love with lace, and North America was quickly adopting sewing machines as involvement in war demanded clothing to be made faster than ever. The dress relates to the wearer as a woman embracing femininity, modernism, style, pride in family, and elegance. The wearer was probably an upper-middle class woman; she could not get it dirty, and she probably needed assistance to put it on. Imagine the wardrobe of someone in the 19th century. Although the garments would be quantitatively less than today’s wardrobe, the quality of each individual garment surpasses those of today. Each dress took much time and energy, not just in the production, but also in the wearing of the garment. In each dress, there is more fabric to carry, more buttons to fasten, etc. To put on the dress would require the assistance of another person. Supporting undergarments include a corset if desired, a crinoline or hoopskirt, and possibly drawers. By studying the dress, I would say that the hair and makeup that accompanied the look would have been equally elegant. The wearer might have had a bun and braids like many women of the Victorian age. She would have worn pastel colors on her face, particularly the cheeks. For shoes, she would have worn low heels of some sort, made from leather. The photos below illustrate possible hairstyles and shoes worn with the dress. c. 1851 retrieved from powerhousemuseum.com retrieved from Englishmuse.com To evaluate and critique the form, the artifact is similar to other dresses of the 1850s. It is constructed using hand and machine sewing, it uses shot silk, displays the distinctive silhouette of the time, and includes a pocket, bust-improver, and engageants. The dress would fit seamlessly into the 1850s. In conclusion, I feel that the dress was very well constructed. I can tell that the dress took much time and energy to put together. I love the dress as a whole, because it has so much depth. If I could put one of those on everyday, I would be honored. Sources Baclawski, K. 1995. The Guide to Historic Costume. Retrieved from pages 53, 88. Bellis, M. 2014. History of the Sewing Machine. Retrieved from: http://inventors.about.com/od/sstartinventions/a/sewing_machine.htm Big Stock Photo. retrieved from: http://www.bigstockphoto.com/image36786773/stock-vector-1800-1900-fashion-silhouettes Cumming, V. 2010. The Dictionary of Fashion History. Page 270 Seabastion. 2014. History of Lace Making. Retrieved from: http://hubpages.com/hub/History-of-Lace-Making Ebay listing. Retrieved from: http://www.ebay.com/itm/DR481-1840-s-IridescentSilk-Blue-Green-Ball-Gownn-/230973327145?ssPageName=ADME:B:SS:US:3160 Englishmuse.com Powerhousemuseum.com