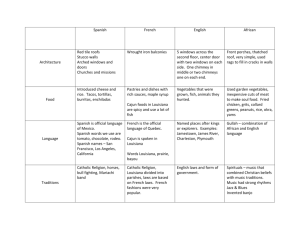

Economics and Ethnic Groups

advertisement

GUIDING QUESTION: How did the events during the colonial period influence growth and development of Louisiana? Companies and Slavery, 1713–1729 Although all French colonies were subject to the same desperate circumstances, the Mississippi colony, as the newest in the French imperial system, fared the worst. Lured by promises of mines and gold, most of the early settlers made little effort to hunt or plant crops. Few farms developed along the banks of the Mississippi or along the sandy coast. Since the earliest settlers were never furnished with adequate food supplies, they frequently resorted to scavenging for crabs, crayfish, and seeds of wild grasses. Whenever possible they traded blankets and utensils for corn and game with the surrounding Native American tribes. Disease, particularly yellow fever, diminished the community. Floods, storms, humidity, mosquitoes, and poisonous snakes added to the misery. Although few settlers escaped the hardships, by far the sturdiest members were those who had accompanied Iberville from Canada. Having maintained direct control over its Mississippi colony for 13 unprofitable years, the French court held less than sanguine prospects for its future development. In an effort to instill vitality into Louisiana, King Louis XIV granted a proprietary charter on September 14, 1712, to the merchant and nobleman, Antoine Crozat. The royal charter afforded Crozat exclusive control over all trading and commercial privileges within the colony for a 15-year period. Crozat gained a monopoly over all foreign and domestic trade, the right to appoint all local officials, permission to work all mines, title to all unoccupied lands, control over agricultural production and manufacture, and sole authority over the African slave trade. In return he was obligated to send two ships of supplies and settlers annually and to govern the colony in accordance with French laws and customs. The colony could neither be governed adequately nor profited from. Estimates placed Crozat's losses in Louisiana at just under 1 million French livres (about $1 billion). Unable to sustain the colony any longer, in August 1717 he petitioned the king and his ministers for release from his charter. Crozat's failure to turn Louisiana to his financial advantage once more made the colony a ward of the crown. In 1717 the Company of the West, run by John Law, took over the slow-growing colony. Law gained great influence at the French court through his establishment of what became the French national bank. Because the bank invested heavily in the Company of the West and because Louisiana was the company's greatest asset, Law needed to develop the colony rapidly to maintain public confidence in the bank. He brought in several thousand settlers through a promotional campaign. 6 In the area that would later become Germany, small kingdoms fought for power. The people who lived there struggled to survive and dreamed of a better life. They read about a Louisiana paradise in handbills printed in their own language. The words of John Law along with their hopeless situation convinced them to take the risk. These German farm families settled on land above New Orleans. The French called this settlement Cote Des Allemandes, the German Coast. These experienced, hard-working farmers cleared the land and planted gardens. They saved the colony by growing enough food to keep the people from starving. Once, when the German farmers brought garden produce to New Orleans, people fought over the food. Soldiers had to be called in to keep order. According to one company official, 7,020 Europeans went to the colony between October 1717 and May 1721. Law's company acquired the Company of Senegal, which held the French monopoly on the slave trade, and black slaves from Africa were brought to Louisiana in 1719. About 3,000 slaves arrived between 1720 and 1731. Immigrants anticipated quick profits with little effort or investment due to Law's promotional literature. However, the harsh world they found was dramatically different. The colonial government could not meet their needs for food, clothing, and shelter and so many people died. Most of the survivors stayed because they lacked the means to return to Europe. Most of the immigrants tilled small subsistence farms, sometimes with slave labor, although a few large plantations were established. These farmers engaged in small-scale production of tobacco and indigo for export. The Mississippi Bubble or Mississippi Scheme, a promotional scheme by Law, fell apart in 1720 as word of the brutal colonial conditions reached France. However, the company continued to administer the colony until 1731. In that year, as a result of French warfare with the Natchez people who lived on the east bank of the Mississippi, Louisiana was returned to the French monarchy. The forced migration of approximately 6,000 enslaved Africans constituted the most significant demographic alteration to French colonial Louisiana during the 1720s. They brought with them knowledge of rice, corn, tobacco, cotton, and indigo cultivation, as well as an assortment of technologies and skills related to craftsmanship, all of which were considered useful for the development of a fledgling colony in the Americas. African slaves interacted with Indian slaves on a daily and intimate basis, effectively undermining the intention of French masters to control the thoughts and actions of their human property. In 1724 French officials implemented the Code Noir in hopes of regulating the everyday lives of enslaved and free people of African descent in Louisiana, much as governments had done in other French colonies throughout the Caribbean. 7 Military and Economic Difficulties, 1729–1754 Economic development in French colonial Louisiana remained limited during the 1720s. The company established Fort Chartres as a way to advance the fur trade in the Illinois Country, only to be greatly disrupted during the wars between the French and the Fox Indians of the late 1720s. English encroachment upon the fur trade in present-day Mississippi and Alabama also diminished French influence among neighboring petites nations. And despite the marginally successful cultivation of tobacco near Fort Rosalie, the so-called Natchez Revolt of 1729 contributed to an economic downturn in Lower Louisiana that lasted through the 1730s. On the morning of November 28, 1729, Natchez warriors killed more than 200 French men, women, and children, and captured around 300 African slaves and 50 French women and children. Rumors of a Natchez conspiracy against Fort Rosalie preceded the attack, in which some enslaved Africans played a role. Approximately 10 percent of Louisiana’s white population died in the attack. The French government responded to the Natchez revolt by disbanding the company and reclaiming Crown authority over Louisiana. Under the leadership of Bienville and with the assistance of the Illinois, Tunica, and other Native American groups, French soldiers spent the next decade conducting a series of military campaigns against the Natchez and Chickasaw. The French had two chief objectives: first, to exterminate what remained of the Natchez, and second, to punish the Chickasaw for harboring Natchez refugees and trading with the English. 8