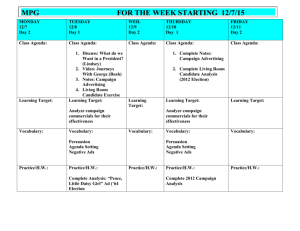

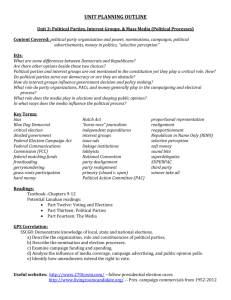

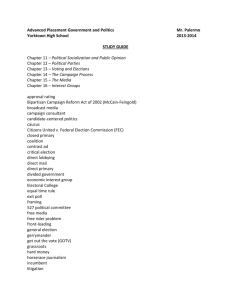

Campaign Finance Online Oversight

advertisement