Introduction

advertisement

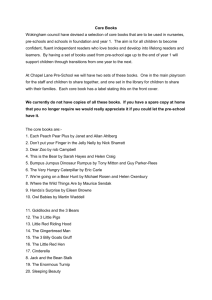

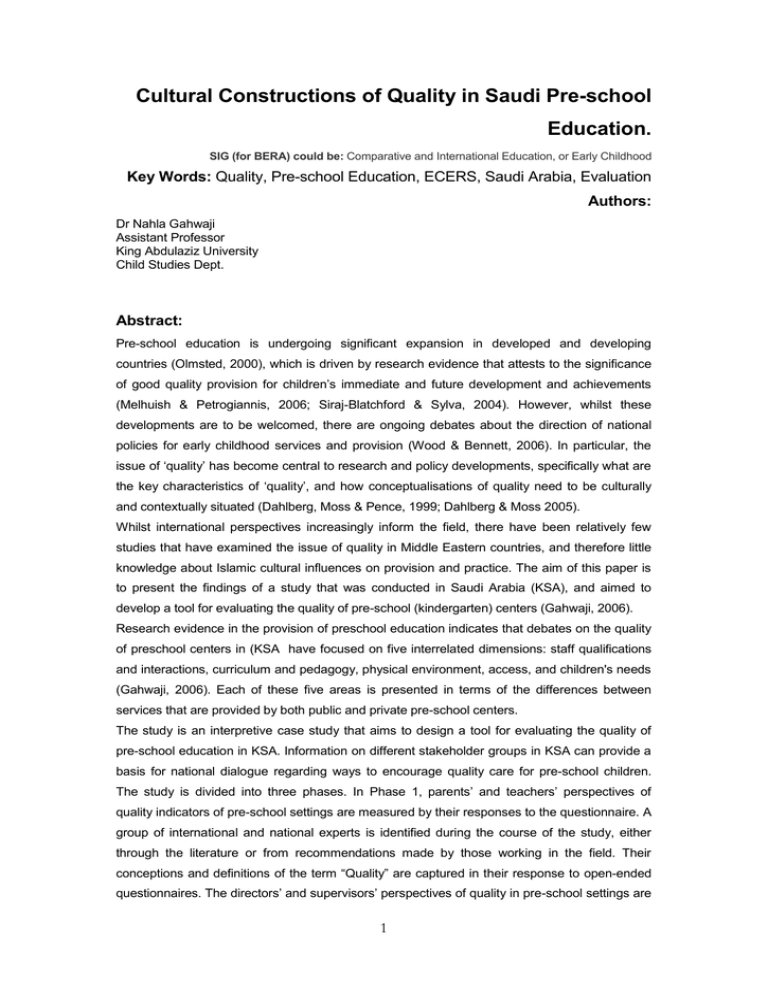

Cultural Constructions of Quality in Saudi Pre-school Education. SIG (for BERA) could be: Comparative and International Education, or Early Childhood Key Words: Quality, Pre-school Education, ECERS, Saudi Arabia, Evaluation Authors: Dr Nahla Gahwaji Assistant Professor King Abdulaziz University Child Studies Dept. Abstract: Pre-school education is undergoing significant expansion in developed and developing countries (Olmsted, 2000), which is driven by research evidence that attests to the significance of good quality provision for children’s immediate and future development and achievements (Melhuish & Petrogiannis, 2006; Siraj-Blatchford & Sylva, 2004). However, whilst these developments are to be welcomed, there are ongoing debates about the direction of national policies for early childhood services and provision (Wood & Bennett, 2006). In particular, the issue of ‘quality’ has become central to research and policy developments, specifically what are the key characteristics of ‘quality’, and how conceptualisations of quality need to be culturally and contextually situated (Dahlberg, Moss & Pence, 1999; Dahlberg & Moss 2005). Whilst international perspectives increasingly inform the field, there have been relatively few studies that have examined the issue of quality in Middle Eastern countries, and therefore little knowledge about Islamic cultural influences on provision and practice. The aim of this paper is to present the findings of a study that was conducted in Saudi Arabia (KSA), and aimed to develop a tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school (kindergarten) centers (Gahwaji, 2006). Research evidence in the provision of preschool education indicates that debates on the quality of preschool centers in (KSA have focused on five interrelated dimensions: staff qualifications and interactions, curriculum and pedagogy, physical environment, access, and children's needs (Gahwaji, 2006). Each of these five areas is presented in terms of the differences between services that are provided by both public and private pre-school centers. The study is an interpretive case study that aims to design a tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school education in KSA. Information on different stakeholder groups in KSA can provide a basis for national dialogue regarding ways to encourage quality care for pre-school children. The study is divided into three phases. In Phase 1, parents’ and teachers’ perspectives of quality indicators of pre-school settings are measured by their responses to the questionnaire. A group of international and national experts is identified during the course of the study, either through the literature or from recommendations made by those working in the field. Their conceptions and definitions of the term “Quality” are captured in their response to open-ended questionnaires. The directors’ and supervisors’ perspectives of quality in pre-school settings are 1 identified through semi-structured and in–depth interviews to identify the formal and informal inspection and evaluation systems of pre-school provision. Classroom observations are conducted using the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale Revised (ECERS-R; Harms, Clifford & Cryer, 1998), the British extension, the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale Extension (ECERS-E; Sylva, Siraj-Blatchford &Taggart, 2003), and the Caregiver Interaction Scale (CIS; Arnett, 1989) in six pre-school centres (3 public and 3 private). Phase 2 includes the designing process of the new rating scale, the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Saudi Arabia Extension (ECERS-SA), the adaptation and translation processes of both the ECERS-R and the ECERS-E, and the trial process of the three rating scales at the In-service Training Centre for Pre-school Teachers in Jeddah. Then the analyses of teachers’ feedback regarding the trial process and the experts’ feedback on the questionnaires are highlighted in response to the relevance, and applicability of the three rating scales. Phase 2 ends with the refining process, which constructs the final form of the ECERSSA. Phase 3 includes measuring the inter-observer reliability of the evaluation tool that is comprised of the ECERS-R, ECERS-E, and the ECERS-SA. It represents evaluations that are performed by supervisors and directors of six pre-school centres (3 public and 3 private). The results are analysed to provide correlations analysis amongst the sub-scales of the evaluation tool, followed by reliability and validity tests, which in turn help in providing a reliable and valid tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school education in KSA. Challenges and concerns accompanying professional and public opinions are discussed based on research evidence (Gahwaji, 2006) and international debates about what constitutes quality in preschool education (Dahlberg, Moss & Pence, 1999; Dahlberg & Moss, 2005; Penn, 2005; Sylva & Pugh, 2005). The paper concludes with considerations of some of the challenges that this change of focus implies. Introduction: Pre-school education is undergoing significant expansion in developed and developing countries (Olmsted, 2000), which is driven by research evidence that attests to the significance of good quality provision for children’s immediate and future development and achievements (Melhuish & Petrogiannis, 2006; Siraj-Blatchford & Sylva, 2004). However, whilst these developments are to be welcomed, there are ongoing debates about the direction of national policies for early childhood services and provision (Wood & Bennett, 2006). In particular, the issue of ‘quality’ has become central to research and policy developments, specifically what are the key characteristics of ‘quality’, and how conceptualisations of quality need to be culturally and contextually situated (Dahlberg, Moss & Pence, 1999; Dahlberg & Moss, 2005). Whilst international perspectives increasingly inform the field, there have been relatively few studies that have examined the issue of quality in Middle Eastern countries, and therefore little knowledge about Islamic cultural influences on provision and practice. The aim of this paper is 2 to present the findings of a study that was conducted in Saudi Arabia (KSA), and aimed to develop a tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school (kindergarten) centres (Gahwaji, 2006). Since most methods and tools are originated and initiated in Western cultures that are based mostly on Western educational theories, the demand for a culturally relevant tool that recognises the diversity among societies is vital ( Penn, 2005). More importantly is to find out quality indicators that are associated with positive child development and learning outcomes based upon stakeholders’ opinions and educational theories in the KSA. The following research objectives that guided the study are as follows: To describe the regulatory standards that have been enforced by representatives of the Ministry of Education (MOE), To analyse the formal evaluation that is imposed by supervisors of the Educational Supervision Office (ESO), To expose parents’ perceptions of quality in pre-school centres, To establish practitioners’ (teachers, directors, and supervisors) perspectives of the quality of pre-school education, To observe a sample of public and private pre-school centres using different evaluation tools (the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS-R; Harms, Clifford & Cryer, 1998), the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Extension (ECERS-E; Sylva, Siraj-Blatchford & Taggart, 2003b), and The Classroom Interaction Scale (CIS; Arnett, 1989) that have been used in previous studies, and to test their utility to the Saudi culture, To translate and adapt different international evaluation tools and methods, and to use those in designing a tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school education on the national level, To apply the evaluation tool, which is the main aim of the study in a sample of pre-school centres to test its reliability and validity, and To make recommendations for policy and practice for pre-school education in KSA. Theoretical Model of the Study In designing the study, several studies have been influential, such as the Effective Provision of Pre-School Education Project (EPPE) (Sylva, Sammons, Melhuish et al., 1999a), and studies by Hadeed (1995;1999), Al-Ameel (2002), and Katz (1999). The EPPE study and this study have some similarities: both studies use different quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the quality of pre-school provision, and its impact on children's development. The EPPE team collected a wide range of information on over 3,000 children, their parents, their home environments and the pre-school settings they attend. In addition to investigating the effects of pre-school provision on young children’s development, a linked project on Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years (EPEY) explored the characteristics of effective practice (and the pedagogy which underpins them) through nine intensive case studies of pre-school settings with positive 3 child outcomes (Siraj-Blatchford, Sylva, Muttock et al., 2002). Further evidence, which is linked to EPPE and EPEY, of Pedagogical Effectiveness in Early Learning is provided by Moyles, Adams & Musgrove (2002). These related projects demonstrate the significance of conceptualising quality and effectiveness from the perspectives of different stakeholders (Pianta, Howes, Burchinal, et al., 2005). Unlike the EPPE, the study sample is much smaller but is representative of effective settings within the overall study sample. Moreover, in the EPPE, the ECERS-R was supplemented by a new rating scale ECERS-E, that was devised by the EPPE team based on the Desirable Learning Outcomes for 3 and 4 yearolds, and associated pedagogical practices (Siraj-Blatchford & Wong, 1999). Because the ECERS was developed in the United States (USA) and was intended for use in Early Childhood Education (ECE) settings, the EPPE team thought it necessary to devise a second early childhood environment rating scale, which was focused on provision in the United Kingdom (UK) as well as good practice in catering for diversity (Sylva et al., 1999a, Sylva & Pugh, 2005). Accordingly, the study attempts to design a tool that is culturally relevant to evaluate the quality of pre-school centres in KSA. As a result, the Saudi extension, the ECERS-SA is developed throughout the study. There have been some studies in the Middle East, which focus on the quality and effectiveness of pre-school provision. The Hadeed study in Bahrain aimed to assess the impact of different types of pre-school centres: the educationally-oriented pre-school centres and the care-oriented pre-school centres, comparing them with the effects of home care. However, the present study investigates the quality of public and private pre-school centres in KSA, as both care and education are typically offered in various ways, and does not include home care. However, both research studies are similar in terms of cultural background and data collection methods. Bahrain and KSA share the same religion, language, and cultural background. Also, the ECERS has been applied in Bahrain without any translation or adaptation since the researcher is bilingual (Hadeed, 1995). Another similarity is that KSA and Bahrain recently started to develop and provide ECE programmes for young children. On the other hand, there are several similarities between Al-Ameel Study and this study. Both studies use the ECERS-R, ECERS-E, and CIS. The only difference is that AL-Ameel investigated the impact of different pre-school settings that vary in their application of the Newly Developed Curriculum (NDC), on several measures of child development in Riyadh city in KSA (Al-Ameel, 2002). In contrast, the study focuses on evaluating the quality of pre-school education as a whole, including aspects related to curriculum and pedagogy. In addition, the study incorporated the use of the ECERS-R and the ECERS-E as measures for evaluating the quality of pre-school centres, but did not develop a specific tool for KSA. The Katz model (1999) is incorporated in the study, which consists of four perspectives on the quality of childcare including: researchers and professionals in the field, parents, staff, and children's themselves. The Katz model is used to guide data collection and data analyses in the study. Hence, the theoretical model becomes a framework for the research study as presented in Figure 1. 4 Figure 1 The Theoretical Model of the Study Stakeholders’ Perspectives Teacher/ Director Process Quality Community/ Culture Children via Parents’ voices Pre-school Quality Expert/ Researcher Parents/ Family Structural Quality International/cultural Contexts Methods: The study design requires utilisation of several approaches to describe and evaluate the nature of pre-school education in KSA, based on quantitative and qualitative data and research evidence. Since the study is divided into three phases that require varied approaches, an interpretive methodology is adopted, with a case study design. As the model demonstrates, the case consists of multiple levels and components, and builds a holistic picture by taking into account information gained at many levels. Accordingly, different methods are required for the different elements, and those methods are guided by existing evidence and theory (De Vaus, 2001). Additionally, the task of the interpretive research is to understand the ways in which meanings are socially constructed, and how these may be open to change and adaptation. Because interpretive researchers become embedded in systems of meaning, they also need to be reflexive about their own perspectives, beliefs, and ways of making meaning from the actions and interactions of others. In the study, there are different layers of interpretation, which are situated in the cultural context. Because the research is situated in KSA, most of data are collected in Arabic, and are translated to English. The process of translation created an additional layer of translating and creating meaning, from the individual interviews and group discussions. Thus, a dual interpretive perspective has been used here: namely interpreting the 5 translated meanings of the key stakeholders and interpreting those meanings in the context of the research aim. Because the aim of the study is to design a tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school education in KSA, it aims to describe some aspects of the Saudi cultural understandings and practices of pre-school education. An interpretive and descriptive qualitative study is conducted in Phase 1, Building Phase for the reason that the research objectives are to find out and understand the perspectives and worldviews of the people involved in pre-school education. Therefore, the researcher seeks out and considers in depth the values and beliefs, needs and agendas, and influence and empowerment of various “stakeholder” groups having an interest in pre-school services. Moss and others referred to all groups who are affected by services, and therefore can be said to have an interest in them, as “stakeholders” (Abbott-Shim, Lambert, & McCarty, 2000). In the study, the term “stakeholders” refers to parents, teachers, directors, supervisors, experts, and children. The study adopts a naturalistic orientation because the study is conducted in its “natural” state, which is pre-school centres in KSA, taking into account the participants’ perspectives as a value-added to the study. Such a position assumes that these kinds of settings, situations, and interactions “reveal data”, and also that it is possible for a researcher to be an interpreter, or “knower” of such data as well as an experiencer, an observer or a participant observer (Azer, LeMoine, Morgan, et al. 2002). In addition, it can be urged that that the researcher can be a “knower” in these circumstances precisely because of a shared “standpoint” with the researched (Mason, 1996). Consequently, by questioning parents and teachers, interviewing directors and supervisors, and by observing teachers and children in their classrooms in pre-school centres, the study is able to describe and interpret the phenomena of pre-school education in an attempt to achieve shared meaning with stakeholders. Wallcott advocated this approach: “Description is the foundation upon which qualitative research is built. Here you become the story teller, inviting the reader to see through your eyes what you have seen, and then offering your interpretation” (Wallcott, 1994:28). In Phase 2, the case study approach is used. As Stake (2000) suggested, case study is less of methodological choice than “a choice of what is to be studied”. The “what” is a bounded system, a single entity, a unit around which there are boundaries (Smith, 1978). The process of conducting the case study begins with the selection of the “case,” which is the In-service Training Centre for pre-school teachers in Jeddah city, KSA. The selection is done purposefully, not randomly; that is, a particular pre-school centre is selected because it exhibits characteristics of interest to the researcher. While this pre-school centre might serve as a “model” for other pre-school centres, it is exceptional in that all teachers are highly qualified and under qualified supervision since they provide training for all pre-school teachers in the city. Furthermore, the NDC, which is the national curriculum in KSA, is applied in this pre-school centre in an ideal way. Phase 2 also draws on elements of the action research cycle, including observing, planning, implementing, reflecting, sharing, and then the cycle repeats itself again. However, the study 6 embodies some principles of action research, but does not aim explicitly to bring about changes in practice. Action research is about researching with people to create and study changes in and through the research process (MacNaughton, Rolf & Siraj-Blatchford, 2001). However, in the study, the actions are taken primarily by the researcher in translating and presenting the ECERS-R, ECERS-E, and CIS in joint actions with the participant centre on applying and evaluating these tools, the contexts of practice, and laying the foundations for the development of the ECERS-SA. The study presents the designing process of the new ECERS-SA and the translation process of both the ECERS-R, and the ECERS-E. For the duration of the trial process, the researcher supports the teachers, and engages collaboratively in the action research cycle. Then the analysis of teachers’ feedback regarding the trial process, and experts’ feedback on the questionnaires regarding the three rating scales, helps in the refining process that constructs the final form of the ECERS-SA. An important aspect of the study is that it combines an “inside-out” and “outside- in” model of action research, which draws on the professional knowledge and experiences of teachers and other stakeholders, in order to enhance the cultural relevance of the new ECERS-SA. Again, the case study approach is used in Phase 3, Implementing Phase. The “case” in Phase 3 comprises six pre-school centres (3 public, and 3 private) instead of one pre-school centre as in Phase 2. Direct observations in different classrooms are conducted by the directors of those pre-school centres besides appointed supervisors from the MOE. The In-service Training Centre for pre-school teachers (which participates in Phase 1 and Phase 2) and one private centre (which participates in Phase 1) participate again in Phase 3 to validate the results of the study. To secure greater reliability and validity in classroom observation, the decision is made to use the strategy of the researcher sitting with both directors and supervisors in the classrooms as a non-participant observer. To clarify observations and gain the directors’ and supervisors’ perspectives, the researcher conducts semi-structured interviews following most observation periods. Demographic and background information on the six pre-school centres are obtained from the directors. Using different data resources, the aim is to triangulate references and perspectives to ensure greater data reliability. The decision to use a combination of data collection methods, both quantitative and qualitative, aims to add “rigour, breadth, and depth of any investigation” (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994: 2). Among others, methodological triangulation among different sources of information is one of the main techniques used. A multiplicity of complementary methods is highly recommended for use in data collection in order that the form of methodological “triangulation” is created (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994). Triangulation can serve as a means of maintaining research findings for bias, for example, and as means of increasing confidence that the data are sound (Siraj-Blatchford & Siraj-Blatchford, 2001). The purpose behind using this methodology is because the aim of the study is to design a tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school education in KSA. Since this tool will not be built from scratch, it depends on methodological triangulation. Methodological triangulation is achieved by applying different methods, including documentary analysis, structured discussions, in-depth interviews, questionnaires, observations, and standardised 7 rating scales. In qualitative research, to triangulate data means to confirm their validity by obtaining data from a second or third methodological resource (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1996). The central aim is to provide a holistic account that captures all the beliefs, views, perspectives, intentions, and values of the subject of the study, which is the evaluation tool. In the context of quality of pre-school education, interpretive research has succeeded in getting below the surface of general evaluation characteristics identified in check-lists and rating scales (Harms et al., 1998; Sylva et al., 1999a, Henry, Ponder, Rickman, et al., 2004). Another interpretive technique used in the study, which is analysis of official documents such as the Curriculum Guidance and Teachers’ Manual of the NDC, teachers’ evaluation forms, and documents stating government’s policies and regulations for pre-school sector. Data Collection Data collection incorporates the following three distinct phases Phase 1: Building Phase, Phase 2: Trial Phase and Phase 3: Implementing Phase as explained in the following tables. Table 1 Phase 1, methods, data sources, and sample Phase 1: Building Phase Method Questionnaires Semi-structured interviews Classroom Observations the ECERS-R,ECERS-E, and CIS Data source sample Mothers 270 Teachers 36 Directors 6 Supervisors 18 3 public ( 1,2,3) Pre-school centres Total = 9 classes 3 private (A, B ,C) ( researcher) Total = 9 classes Note: (1) and (B) are the centres that continue in the three phases Table 2 Phase 2, methods, data sources, and sample Phase 2 : Trial Phase Method Data source Sample Questionnaires Supervisors 12 8 Experts 12 Classroom observations The ECERS-R, ECERS-E, and 1 public (1) pre-school centre the new ECERS-SA٭. Total = 9 classes Structured discussions Tracking sheets Teachers 12 Note: ( ٭Arabic version) is used in phase 2, (1) is the centre that continues in the three phases Table 3 Phase 3, methods, data sources, and sample Phase 3: Implementing Phase Method Data source Sample 6 Directors 6 Classroom observations Supervisors The Evaluation Tool Pre-school centres 3 public ( 1,4,5) (ECERS-R, ECERS-E, and the Total = 9 classes ECERS-SA).٭ 3 private (B,D,E) Total = 9 classes Note: ( ٭Arabic version) used in Phase 3; (1) and (B) centres that participate in the three phases The research plan of the study as shown in Figure 2 illustrates the research methods which follows the chronological order of the methods as they are used in the three phases. 9 Figure 2 The Research Plan Research Plan Designing Revising Data collection methods Piloting Questionnaires Parents- TeachersExperts Phase 1 Building Phase (The building of ECERS-SA) Observations ECERS-R-, ECERS-E and CIS. Researcher Semi-structured Interviews Directors- Supervisors Observations (Adapted and translated ECERS-R, ECERS-E and ECERS-SA Structured Discussions Tracking Sheets Teachers-Researcher Phase 2 Trial Phase (The trial of the ECERS-SA) Questionnaires Supervisors -Experts The Evaluation Tool Consisting of ECERS-R, ECERSE and ECERS-SA Observations Directors-supervisors Phase 3 Implementing Phase (The trial of the evaluation tool) 10 The process will continue Methods Questionnaires: Mothers will answer the parents' questionnaire that includes various questions about the childcare currently offered by pre-school centres, or characteristics that they look for when they are searching for pre-school settings for their children. Mothers are chosen because the preschool level in KSA is under the supervision of the girl’s section at the MOE. Typically, mothers interact and participate in their young children’s pre-school experiences; this notion is true for both boys, and girls since the pre-school years are co-educational in KSA. The parents’ questionnaire contains seven sections as follows, background information, learning environment, children’s needs, teacher interactions, curriculum and pedagogy, administration and directing, and supplementary questions. A total of 270 questionnaires are distributed in all the three levels (Kg-1, Kg-2, and Kg-3) in six pre-school centres. Two hundred and fifteen are returned to the researcher through the directors of the centres, a response rate of 79.63%. The teachers’ questionnaire contains seven sections that are similar to the parents’’ questionnaire except for the first section that includes two parts, teachers’ information, and information regarding the pre-school centre and classroom. The teachers of three classes that represent the three levels of pre-school education in each pre-school centre are randomly chosen by the director to participate in the study (for a total of 36 teachers). All questionnaires are returned, a response rate of 100%, because the researcher administers the questionnaires at the beginning of staff meetings. Most of the questions are intentionally made identical to those in the parents’ questionnaire so that direct comparisons can be made; others are omitted because of their insignificance to the study. Questionnaires are sent to experts in the field of ECE, that are identified as leading researchers in the field in their own countries and internationally since their feedback will direct to valuable sources of information regarding the quality of pre-school provision. The expert' questionnaire contains three sections as follows, background information, research aims, and the evaluation tool. The first section includes questions about the education level, major and minor subjects, profession and length of work in the profession, and their prior experience and area of expertise. In addition, the questionnaire asks for information regarding three areas that are related to the study including quality of pre-school education, evaluation, and assessment of pre-school centres, and policy and regulations about pre-school settings (Barnett, 2002). The second section seeks information about the research studies of the experts and their relation to the field of quality in pre-school provision. The third section includes questions concerning indicators of quality, main points of the subject matter (the evaluation tool), and opinions about an appropriate rating system that should be considered when the study designs the evaluation tool. Interviews: In Phase 1, data are collected through semi-structured interviews with the directors of the preschool centres in the sample and supervisors from the ESO. The interviews last for 11 approximately one hour and are conducted in Arabic then translated to English by the researcher. The directors’ interview is conducted in each pre-school centre before the direct observation of the classrooms while the supervisors’ interviews are conducted at the main office of the ESO. Some of the participants provide written documents of their own work that address some of their involvement in evaluating the quality of pre-school centres, evaluating teacher’s performance, and/or issues directly related to their work offering further clarification on issues that are discussed. Thus, the multiple sources of data collection, methods of interviews, and documents are a means of triangulation. The interview schedule consisted of open-ended questions regarding the issues, concerns, and perspectives of quality pre-school programmes. Interview schedules are first written in English, and then translated to Arabic to be administered to the sample. The directors’ interview covers eight criteria: background information, the learning environment, children’s needs, teachers’ interactions, curriculum and pedagogy, administration and directing, quality of pre-school centres, and the evaluation tool. The directors are asked several openended questions. The questions are categorised into those relating to classrooms, facilities, equipment, and materials. In addition, the directors are asked to state their opinions about the curriculum and pedagogy, and the national framework in their centre regarding administration policies and services. The supervisor interview is divided into four sections: background information, teachers’ performance, quality of pre-school centres, and the evaluation tool. The supervisors are asked several questions about the quality indicators, design, contents, and the rating system of the evaluation tool. They are asked to state quality indicators that should be considered when the researcher designs the tool for evaluating quality of pre-school centres. In addition, the supervisors are asked to suggest a format and an appropriate rating system for the evaluation tool. Classroom Observations: Classroom observations in Phase 1 are conducted using the ECERS-R, the ECERS-E, and the CIS to determine the quality of pre-school education and to compare the different levels of quality of a sample of pre-school centres in Jeddah city, KSA. The information is gathered by observations and interviews, and the goal is to establish a picture of the different levels of quality for the pre-school centres in the sample. This picture helps to construct the basis for designing the tool for evaluating the quality of pre-school education in KSA. The data collection procedures involve observing one classroom for 4 days over four hours during the morning (for a total of 16 hours), reviewing specific classroom documents, and interviewing the teacher for approximately 20 minutes during a break or at the end of the day. Typically, data are collected in each pre-school centre during a three-week period. Classroom observations are conducted in 18 classrooms in six pre-school centres where the task of the researcher at the end of classroom observations is to translate and adapt the scales and develop the new ECERS-SA. 12 After the development of the ECERS-SA, and the translation and adaptation of both the ECERS-R and ECERS-E, direct observations are conducted by teachers with the support of the researcher just in one pre-school centre, which is the In-service Training Centre for pre-school teachers. The teachers use the translated and adapted ECERS-R and ECERS-E, in addition to the newly designed rating scale, the ECERS-SA. The trial process in Phase 2 is divided into three stages including: introducing, training, and administering. The introducing stage is about explaining the three rating scales to explore the aim of the study and the purposes of the trial process. All the teachers are provided with a full day’s session on what is meant by “quality”, the culturally specific aspects of it, as well as the international aspects such as studies in Europe and the Western countries. In addition, the researcher explains the aim of the study and outlines the three phases of data collection and analysis. The training stage follows the introduction stage where the entire center staff members are encouraged to participate in the inservice training sessions. The teachers conduct several “trial” observations in order to familiarise themselves with the contents of the items included in the ECERS-R. Once the training is completed, the teachers administer the three rating scales and start the trial process. Administering the three rating scales together is the last stage in the trial process. During the implementing stage, the teachers are provided with tracking sheets to write their comments regarding each sub-scale in terms of suitability of items, examples provided, and concepts and terms. The teachers regularly report to the researcher their discussions and progress regarding the three rating scales at the weekly meeting. These data contribute to the case study approach, by providing detailed contextually situated perspectives on the research process. The revised ECERS-SA needs to be validated; therefore, the revised version is introduced to two groups of experts. The first group consists of twelve faculty members from the faculty of education. The second group consists of twelve supervisors from the ESO, Jeddah division. Both groups at separate times are invited to the conference room at the Faculty of Education at KAAU to complete a questionnaire. The arrangement is meant to guarantee that each subscale of the rating scale is reviewed at length, any uncertainty arising from the questionnaire is elucidated and to allow verbal feedback on the scale’s length, clarity, and relevance to the Saudi culture. Phase 3 is conducted in six pre-school centres (3 public and 3 private). Two centres (1 and B) from the previous list of Phase 1 participate again in Phase 3 to validate the results of the study. The directors and the supervisors in 18 classrooms conduct similar observations during the data collection periods. Phase 3 involves implementing the new evaluation tool that consists of the adapted and translated versions of the ECERS-R and the ECERS-E, and the new rating scale (ECERS-SA). For the purpose of the study, the three rating scales are translated into Arabic so that directors and supervisors can use it successfully. They are provided with detailed definitions for each term to ensure that each aspect of each quality indicator is measured properly and in a comparable manner in each pre-school centre. To secure greater reliability and validity in classroom observation, the decision is made to use the strategy of the researcher sitting with both directors and supervisors in the classrooms as a non-participant observer. 13 Results: The paper aims to provide the results of the Phase 3 since evidence shows that the participants (directors and supervisors) indicate clearly what other change processes are necessary in preschool education, if the evaluation tool is to be used successfully. They are not pointing up constraints or barriers, but are providing positive comments about how this might work in practices (Henry, Ponder, Rickman, et al. 2004). The findings also indicate that the supervisors seem much more willing to problematise the practices that they observe across a range of settings. In contrast, the directors seem to have a less critical view about quality. Although interobserver agreement is established for both observers before starting the evaluation process, the supervisors tend to rate pre-school centres slightly lower than the directors. A question arises from the evaluation process, which is whether the directors have given an “ideal” version of quality in their settings. This may be because they want to present themselves and their centres in a good light. The supervisors seem to be more reflective, more honest, and more critical about the problems and challenges. With the exception of the ECERS-E total scores, the public centres in the sample tend to have slightly higher total scores than private centres. The ECERS-R scores tend towards the top of the “adequate” range and sometimes approach the “good” range. This is an interesting point for discussion. The private centres have good scores, even though their curriculum and pedagogy are more formal. Therefore, does the ECERS-R adequately capture the nature of quality in curriculum and pedagogy? This issue may indicate that the ECERS-R captures structural rather than process characteristics of quality provision (Moss, et al. 2004). These findings have implications for more research to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the ECERS-R. The findings indicate that the ECERS-E scores are more satisfactory and approach above the “good” range because there is a growing national movement towards preparing children for elementary school (Khalifa, 2001). As expected, the scores for the private centres are slightly higher than the public centres, since most private centres in KSA provide educational activities in their curriculum. The lowest scores are found in the sub-scale, ’scientific concepts’ in view of the fact that according to the NDC guidelines, all pre-school centres have a science corner and daily science activities. Based on findings of Phase 2, the problem is that most pre-school teachers in the sample lack the necessary training to stimulate children’s scientific thinking and abilities. While the ECERS-SA total scores are above the “good” range, the public centres’ scores approach the “excellent” range. The reason for these high scores compared to the other scores of both the ECERS-R and ECERS-E is because public centres tend to pursue firmly the NDC guidelines, which conform to the ECERS-SA sub-scales. In addition, for the subscale ‘management’ the directors of the public centres ensure that practices in their centres are in accordance with the guidelines of the NDC and the regulations of the MOE. The highest scores are found in “teachers’ interactions” followed by “cultural influence”, while the lowest scores are seen in “management”. There are not enough data to present the results for the “supplementary services” sub-scale because the public centres in the sample do not 14 provide additional services such as introduction of English or use of computers in their facilities. Obviously, there is a wide variation in the mean scores for the “management” subscale between public and private centres since the policy and regulations regarding administration and directing are administered directly by the MOE in the public sector. Phase 3 aims to discover whether the evaluation tool, consisting of adapted and translated versions of ECERS-R and ECERS-E in addition to the ECERS-SA, submits to the same reliability and validity characteristics as both the ECERS-R and ECERS-E in previous studies. The scores for the two observers (director and supervisor in each centre) across all the subscales of the evaluation tool are analysed by using Kappa statistic. The Kappa for inter-observer agreement is 0.86. The percentage agreement is 91%. These reliability figures are a sign of acceptable inter-observer reliability and are in line with the results from other research (Harms et al., 1998; Sylva et al., 1999a). To test the validity of the evaluation tool, Pearson correlations and Descriptive Analysis are used to compare global ECERS-R, ECERS-E and ECERS-SA scores for each pre-school centre in the sample. The high correlations among the sub-scales of the three rating scales indicate that whenever a pre-school centre scores high on one sub-scale of one rating scale, it is likely to score high on another sub-scale of another rating scale as well (Magnuson, Meyers, Ruhm, & Waldfogel, 2004). Also, the correlations between the ECERS-R and ECERS-E subscales show wide variation. The results of the study are similar to the results of the EPPE study (Sylva et al., 1999a). In addition, it matches the results obtained by Al-Ameel (2002). The correlation analysis between the ECERS-SA and ECERS-R sub-scales show many similarities as well as the correlation with the ECERS-E sub-scales. The overall results of the Pearson Product Moment correlation show a strong relationship amongst the sub-scales of the evaluation tool with the view that they are tapping into “Quality” whilst measuring to some extent diverse features and representing different indicators. The factor analysis of the ECERS-SA sub-scales clearly indicates the existence of only two factors, the remaining components accounting for only a small amount of variance. Clearly, the two-factor solution of the study analysis is closer to the factor structure found in both the EPPE study and ECERS factor analysis. Peisner-Feinberg and his colleagues (2006) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis on the ECERS using data obtained from the USA, Germany, Portugal, and Spain. They confirm the presence of two factors: the first is called “Teaching and Interaction” and is very similar to the second factor of the EPPE study, and the other factor is called “Space and Materials” and closely resembles the first factor of the EPPE study (PeisnerFeinberg, E. & Maris, C, 2005). The results of the factor analysis of the ECERS-E sub-scales yield almost identical results to those found in the EPPE study (Sylva et al., 2003a). It is apparent that mathematics is a minor exception in the factor analysis of the EPPE but it is mostly highly loaded on Factor 2 in the ECERS-E factor analysis of the study. Again, most of the items related to Factor 2 are in line with results obtained in the EPPE. For the ECERS-SA, the factor analysis of the sub-scales indicates the existence of two factors. This two-factor solution demonstrates a similar pattern described by the EPPE (Sylva et al., 15 2003b), with the first factor including items pertaining to culturally appropriate activities and materials, or simply “Materials”, and the second factor includes an item pertaining to developmentally appropriate caregiver interactions, or simply “Interaction”. Since the ECERSSA is a newly developed rating scale, a combined factor analysis is conducted for the first time in the present study. The combined three rating scales scree plot resembles the ECERS-R scree plot, indicating the existence of two factors again. Again, the result is in line with the results of the EPPE (Sylva, Siraj-Blatchford, Melhuish et al., 1999b; 1999c). Again, Cronbach’s Alpha is high for both factors (Alpha = 0.98 for factor 1 and Alpha = 0.92 for factor 2) indicating there is a good internal consistency in both factors. These findings are consistent with findings from the EPPE (Sylva et al., 2003b). This indicates that the new evaluation tool for KSA stands up to international scrutiny against the established tools. This finding is important for the possible future use of the ECERS-SA in neighbouring Middle East countries, with similar religious and cultural traditions. Conclusions: Obtaining views from different stakeholders is a significant problem in the present study. Whose view should best inform the quality debate? The study shows that stakeholders’ perspectives show areas of agreement and disagreement. Whilst some of these perspectives have been accommodated in the evaluation tool, it is perhaps inevitable that the “professional” perspective is ultimately the strongest voice. This is because the professional community (researchers, teachers, supervisors, directors, policy makers) become the advocates and guardians of quality, because of their professional knowledge and expertise. However, an important part of this guardianship is listening and responding to stakeholders’ perspectives, particularly children, parents, and families. The various ECERS used in the study (ECERS-R, ECERS-E, ECERS-SA) set the frame of references against which aspects of quality can be measured. However, further research would need to be conducted on how the evaluation tool is used in practice in KSA, how teachers, directors, and supervisors identify areas for change and development, and how change and development can be brought about. There is a need to evaluate the extent to which ECERS maintains a “status question” – a set of characteristics, which are set in a particular temporal, social, and political context. Alternatively, further research is needed in order to establish to what extent ECERS might contribute to increasing professionalisation, improving quality, and contributing to greater autonomy and reflexivity on the part of teachers, directors, and supervisors. The evaluation tool should help ECE teachers to become more professionally skilled and competent. If the tool is adopted, future research will need to be undertaken to track and evaluate subsequent change processes, and impact factors. ECERS-SA can be used at school level, at district, and at state levels, to monitor the performance of individual centres, and to monitor change and improvement of centres, teachers’ competence, and children’s achievements. Thus, the findings of the study potentially mark an important point on the “quality journey” for the KSA. 16 Refrences Al-Ameel, H. (2002). The effects of different types of preschool curricula on some aspects of children's experience and development in Saudi Arabia. PhD thesis, School of Social Science, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK. Abbott-Shim, M., Lambert, R., & McCarty, F. (2000). Structural model of Head Start classroom quality. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15 (1), 115-134 Arnett, J. (1989). Caregivers in day-care centers: Does training matter? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 10(4), 541. Azer, S., LeMoine, S., Morgan, G., Clifford, R. M., & Crawford, G. M. (2002). Regulation of child care. Early Childhood Research & Policy Briefs, 2(1). Also available at http://www.fpg.unc.edu/~ncedl/PDFs/RegBrief.pdf. Barnett, W. S. (2002). Early childhood education. In A. Molnar (Ed.), School reform proposals: The research evidence (pp. 1-26). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Dahlberg, G., Moss, P. & Pence, A. (1999) Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care: Postmodern Perspectives, London, Falmer Press Dahlberg, G. & Moss, P. (2005) Ethics and Politics in Early Childhood Education, London, Routledge Falmer De Vaus, D. (2001). Research design in social research. London: Sage. Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (1994). Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage. Gahwaji, N. (2006). Designing a Tool for Evaluating the Quality of Preschool Education in Saudi Arabia. PhD Degree thesis, College of Education and Lifelong Learning, University of Exeter, UK. Goodwin, W., & Goodwin, L. (1996). Understanding quantative and qualitative research in early childhood education. New York: NY, Teachers College Press. Hadeed, J., & Sylva, K. (1995). Does quality make a difference in the preschool experience in Bahrain? The European Conference on the Quality of Early Childhood Education. Paris, France. Hadeed, J., & Sylva, K. (1999). Behavioral observations as predictors of children's social and cognitive progress in day care. Early Child Development and care, 154, 13-30. Harms, T., Clifford, R., & Cryer, D. (1998). The Early childhood environment rating scale (revised edition).New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Henry, G., Ponder, B., Rickman, D., Mashburn, A., Henderson, L., & Gordon, C. (2004). An Evaluation of the Implementation of Georgia’s Pre-K Program: Report of the Findings from the Georgia Early Childhood Study (2002-03). Atlanta, GA: Georgia State University, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies. Khalifa, H. (2001). Changing childhood in Saudi Arabia: A historical comparative study of three female generations. PhD Thesis. Hull University. Katz, L. (1999). Multiple perspectives on the quality of programs for young children. The 4th International conference of OMEP-Hong Kong., Hong Kong. MacNaughton, G., Rolf, S., & Siraj-Blatchford, I. (Eds.) (2001). Doing early childhood research education. Buckingham: Open University Press. 17 Magnuson, K.A., Meyers, M.K., Ruhm, C.J., & Waldfogel, J. (2004). Inequality in preschool education and school readiness. American Educational Research Journal, 41, 115-157. Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching. London: Sage. Melhuish, E. & Petrogiannis, K. (2006) Early Childhood Care and education, London, Routledge Moss, P., Petrie, P., Cohen, B., Wallace, J., Flising, B., & Flising, L. (2004). A new deal for children? Re-forming education and care in England, Scotland and Sweden. London: The Policy Press. Moyles, J., Adams, S., & Musgrove, A. (2002). Study of pedagogical effectiveness in early learning (SPEEL) research report No. 363. London: Department for Education and Skills, HMSO. Olmsted, P. (2000) Early childhood education throughout the world, Brown, S., Moon, R. & Ben-Peretz, M. (Eds) International Companion to Education London, Routledge. Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., & Maris, C. L. (2005). Evaluation of the North Carolina More at Four Pre-kindergarten Program: Year 3 Report (July 1, 2003-June 30, 2004). Chapel Hill, NC: FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., Elander, K. C., & Maris, C. L. (2006). Evaluation of the North Carolina More at Four Pre-kindergarten Program: Year 4 Report (July 1, 2004-June 30, 2005) Program Characteristics and Services. Chapel Hill, NC: FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Penn, H. (2005) Understanding Early Childhood, issues and Controversies, Maidenhead, Open University Press Pianta, R., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Bryant, D., Clifford, R., Early, D., & Barbarin, O. (2005). Features of pre-kindergarten programs, classrooms, and teachers: Do they predict observed classroom quality and child-teacher interactions? Applied Developmental Science, 9,144-159. Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Siraj-Blatchford, J. (2001). Surveys and questionnaires: An evaluative case study. In G. MacNaughton, S. Rolfe & I. Siraj-Blatchford (Eds.), Doing early childhood research: International perspectives on theory and practice (pp. 149-161). Buckingham: Open University Press. Siraj-Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Muttock, S., Gilden, R. & Bell, D. (2002) Researching effective pedagogy in the early years (REPEY). Department for Education and Skills. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Research report No 356. Siraj-Blatchford, I. & Sylva, K. (2004) Researching pedagogy in English pre-schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(5), 713-730. Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Wong, Y.-L. (1999). Defining and evaluating 'quality' in early childhood education in an international context: Dilemmas and possibilities. Early Years, 20(1), 718. Smith, L. (1978). An evolving logic of participant observation, educational ethnography and other case studies. In L. Schulman (Ed.), Review of research in education. Itasca, IL: Peacock. Stake, R. (2000). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research, (2nd ed.), (pp. 435-454). Thousand Oak, CA: Sage. 18 Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., & Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2001). The Effective Provision of Preschool Education (EPPE) Project. The EPPE Symposium at BERA Annual Conference. University of Leeds, UK. Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., & Elliot, K. (2003a). The EPPE Project: Findings from the pre-school period (summary).London: Institute of Education, DfES/Sure Start. Sylva, K., & Pugh, G. (2005). Transforming the early years in England. Oxford Review of Education, 31(1), 11-27. Sylva, K., Sammons, P., Melhuish, E., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (1999a). Technical paper 1: An introduction to the EPPE project. London: Institute of Education, University of London/DfEE. Sylva, K., & Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2001). The relationship between children's development progress in the pre-school period and two rating scales, International ECERS network Workshop .Santiago, Chile. Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Taggart, B., Evans, E., et al. (1999b). Technical paper 6: Characteristics of the centres in the EPPE sample: Observational profiles. London, UK: University of London, Institute of Education, DfEE/Sure Start. Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Taggart, B., Evans, E., et al. (1999c). Technical paper 6a: Characteristics of pre-school environmental. London: institute of Education/DfEE. Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2003b). The early childhood environmental rating scale: 4 curricular subscales. London: Trentham Books. Sylva, K. & Pugh, G. (2005) Transforming the Early Years in England, Oxford Review of Education, 31: 1, March 2005, 11-27 Wolcott, H. (1994). Transforming qualitative data: Description, analysis, and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Wood, E. & Bennett, N. (2006) Learning, pedagogy and curriculum in early childhood: sites for struggle, sites for progress. In L. Verschaffel, F. Dochy, M. Boekarts, & S. Vosniadou, (Eds.) Instructional Psychology: Past, present and future trends: Essays in Honour of Erik de Corte. European Association for Research in Learning and Instruction, Advances in Learning and Instruction. Elsevier 19