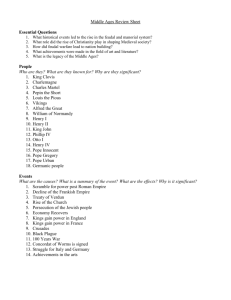

Europe 500-1500 AD - Chandler Unified School District

advertisement