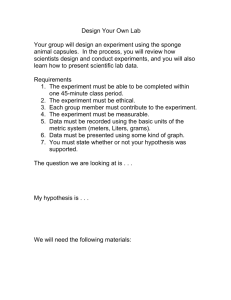

Full Text (Final Version , 558kb)

advertisement