Here - ADDMG

advertisement

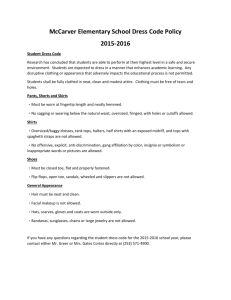

Update on the Law and Tactics of Product Design Trade Dress Infringement By Stephen D. Milbrath September 14, 2015 Trade Dress Generally Trade Dress involves the “total image of a product and may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, graphics, or even particular sales techniques. AmBrit, Inc. v. Kraft, Inc., 812 F.2d 1531, 1535 (11th Cir. 1986). Product Shape It is easy to think of trade dress as referring to packaging and labeling, and possibly coloring of a product. But it may also include the “design features of the product itself.” Restatement 3rd Unfair Competition, §16, Comment. Thus shape and design of the product can be conceived of as protectable by trade dress. Can A Boat Sheer Line Design Be Protected By Trade Dress Under Section 43 (a) of the Lanham Act? “Yellowfin’s Unique Sheer Line . . . Comprises Yellowfin’s Trade Dress Rights in its Boat Line.” A Sheer Line is the Break in the Hull of a Boat. Is it thus a functional feature? Can An Exhaust Manifold for a Marine Engine Incorporate Primarily Nonfunctional Features? Can Such An Exhaust Manifold Incorporate Primarily Nonfunctional Attributes Capable of Protection? The Benefits to Registration Under Section 2(f) McAirlaids, Inc v. Kimberly –Clark Corp., 756 F.3d 307, 311-312 (4th Cir. 2014): “The presumption of validity that accompanies registered trade dress ‘has a burden-shifting effect, requiring the party challenging the registered mark to produce sufficient evidence’ to show that the trade dress is invalid by a preponderance of the evidence… Therefore, Kimberly-Clark – the party challenging a registered mark– has the burden of showing functionality by a preponderance of the evidence in this case, whereas in TrafFix, MDI– the party seeking protection of an unregistered mark – had the burden of proving nonfunctionality. Even if Design, Like Color is Not Inherently Distinctive, It Might Be Protected By Registration In Some Cases • Lanham Act Section 2(f): “The Commissioner may accept as prima facie evidence that the mark has become distinctive, as used on or in connection with the applicant’s goods in commerce, proof of substantially exclusive and continuous use thereof as a mark by the applicant in commerce for the five years before the date on which the claim of distinctiveness is made.” • This requires direct or circumstantial evidence that the relevant buying class associates the mark with the applicant plus proof of 5 years’ use • The PTO can accept evidence of ownership of one or more prior registrations of the same mark for the same or closely related goods The Danger of Patent-Like Protection For Unpatented Features Recent Supreme Court cases have been cautious in considering this concept. In Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205, for example, The Court stated: Trade Dress is “a category that originally included only the packaging or ‘dressing’ of a product, but in recent years has been expanded by many courts of appeal to encompass the design of a product.” An Over Expansive Resort to Trade Dress? McCarthy on Trademarks has observed that in the 1990s, there was a wave of “over expansive and inflated claims of trade dress and product shapes and features.” McCarthy on Trademarks, §8:5 at 8-30. McCarthy further observes: Many of these courts were concerned because the policy of free competition dictates that trade dress law does not create “backdoor patents”, substituting for the strict requirements of utility patent law. McCarthy, §8.5 at 8-31. The Supreme Court has picked up on this concern: • Product shape is not likely to be perceived as an indicium of origin. TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 121 S. Ct. 1255, 1260 (2001). • Cautioning against misuse or overextension of trade dress. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205 (2000) • “Product Design almost invariably serves purposes other than source identification.” TrafFix, 121 S. Ct. at 1260, emphasis added. The Tension Between Patent Law and Trade Dress Protection Law • Many courts have noted that there is a tension between patent law and trademark law in the area of trade dress protection. See, e.g., Dorr-Oliver, Inc. v. Fluid-Quip, Inc., 94 F.3d 376 (7th Cir. 1996). • McCarthy’s recommendation: “One way to balance trade dress in parent law is to presume that no likelihood of confusion is created as to look-alike highprice goods bought only by professional buyers when the Defendant clearly displays its name on the product.” McCarthy on Trademark §8:5 at 8-32, emphasis added. • The Second Circuit has also observed that “granting trade dress protection to an ordinary product shape would create a monopoly in the goods themselves.” Landscape Forms, Inc. v. Columbia Cascade Co., 113 F.3d 373 (2d Cir. 1997). • See also Yurman Design, Inc. v. PAJ, Inc., 262 F.3d 101 (2d Cir. 2001) (dismissing a trade dress claim alleged to reside in a line of jewelry because of a lack of specificity in pleading the specific elements of the claim dress). The 11th Circuit Case Law In the 11th Circuit, the design of a product may constitute protectable trade dress under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act. Epic Metals Corp. v. Souliere, 99 F.3d 1034, 1038 (11th Cir. 1996). The usual elements of a product design trade dress infringement claim in the 11th Circuit are: 1. The product design of the Defendant’s product must be confusingly similar to the product design of the Plaintiff’s product; 2. The Features of the product design in question must be primarily non-functional; and 3. The product design must be inherently distinctive or must have acquired secondary meaning. Dippin’ Dots, Inc. v. Frosty Bites Distrib., LLC, 369 F.3d, 1197, 1202 (11th Cir. 2004). The Gale Group Case A representative early 11th Circuit case is Herb Allen’s Gale Group, Inc. v. King City Industrial Co., 23 U.S.P.Q.2d 1208 (M.D. Fla. 1992). The Allen, Dyer firm represented Plaintiff Gale, an Orlando company which developed shade structures using a knitted fabric cover and sold under the trademarks PORTASHADE® and GAZEBO®. Gale sued two other companies offering similar shade structures that emulated the designs of the Gale products. Mr. Allen defined the product design trade dress to include: • Triangular leg configuration • Unique roof configurations for the PORTASHADE or GAZEBO • The district court held that Plaintiff had proven that the triangular leg configurations either alone or together with the unique roof configurations were distinctive and had acquired secondary meaning. The court also concluded that the Defendant shade structures were confusingly similar to those of Gale and that actual confusion had also been established and enjoined the Defendants from selling or distributing their similar shade products. A Series of Important Supreme Court Cases A series of important Supreme Court cases have severely restricted the scope of product design trade dress protection. Qualitex Company v. Jacobson Prods. Co. 514 U.S. 159 (1995) • While color can be protected as a trademark, colors as a category of marks must be shown to be inherently distinctive. Hence a plaintiff must show secondary meaning when attempting to prove a product design trade dress built on color, such as a single color. This is because color does not automatically tell the customer that it refers to a brand and does not immediately signify that brand or a product source even though over time customers may come to treat a particular color on a product or packaging as signifying a particular brand. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205 (2000) Here the Court held that design like color is not inherently distinctive. Instead: The attribution of inherent distinctiveness to certain categories of word marks and product packaging arise from the fact that the very purpose of attaching a particular word to a product, or encasing it in distinctive packaging, is most often to identify the source or product … In the case of product design, as in the case of color, we think consumer predisposition to equate the feature with the source does not exist. Consumers are aware of the reality that, almost invariably, even the most unusual product designs – such as cocktail shaker shaped like a penguin – is intended not to identify the source, but to render the product itself more useful or more appealing. 529 U.S. at 214, emphasis added. “Consumers should not be deprived of the benefits of competition with regard to the utilitarian and esthetic purposes a product design ordinarily serves by a rule of law that facilitates plausible threats of suit against new entrants based upon alleged inherent distinctiveness.” Id. • The court drew a clear distinction between trade dress for product packaging, which can be protected on grounds of inherent distinctiveness, and product design trade dress, which cannot be so protected. • “We hold that in an action for infringement of unregistered trade dress under section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, products designed as distinctive, and therefore protectable, only upon a showing of secondary meaning” 529 U.S. at 216. Implications of Qualitex and Wal-Mart Secondary meaning is now required to achieve the status of a protectable trade dress for at least a single color and for the design of the product or its configuration. As a result of this precedent, there will often be a dispute in product design cases on whether the claimed dress is in fact a product design or mere packaging. Secondary meaning is required for the design, but not for the packaging, at least if the packaging is inherently distinctive. The issue of whether the claimed trade dress is a product or a package design is a question of fact. In re Slokevage, 441 F.3d 957 (Fed. Cir. 2006). Wal-Mart In close cases, the court must err on the side of caution and classify the claimed trade dress, if ambiguous, as one of product design, and therefore requiring secondary meaning. Wal-Mart, 120 S.Ct. at 1346. TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc. (2001) • MDI sued for trade dress infringement after its two utility patents had expired on its chief product: a dual-spring road sign. Defendant admitted it made a look-alike and claimed the right to do so. Because the defendant’s signs were covered by the expired patents, the Court held that they were unprotectable as trade dress even if source-identifying in nature. Two seemingly categorical rules: – If features claimed to be part of a trade dress are covered by expired utility patents, the plaintiff has a heavy burden of showing that the features are merely ornamental, incidental or an arbitrary aspect of the claimed invention – If they are not merely ornamental, it does not matter if the features are source identifying if the feature is essential or affects the costs or quality of the product The Restaurant Exception In Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763, 768 (1992), the Supreme Court held that a particular Tex Mex restaurant appearance and décor was inherently distinctive in the category of restaurant services. In WalMart, the Supreme Court distinguished Two Pesos, and held that the décor of a restaurant is not product design, but essentially product packaging, and thus that no proof of secondary meaning is necessary for a building design and décor that is inherently distinctive. The upshot is that a building decor may be so unusual as to qualify as one that is inherently distinctive, but a product design may not. An Eleventh Circuit Example An illustrative case involving the interior design and décor of a restaurant is Miller’s Ale House, Inc. v. Boynton Carolina Ale House, LLC, 702 F.3d 1312 (11th Cir. 2012). In that case, Miller’s Ale House claimed that its competitor had adopted a trade dress that was confusingly similar to Miller Ale House’s unregistered trade dress In considering whether summary judgment had properly been granted against Miller’s Ale House, the court applied the so-called Seabrook Test in determining whether the décor and restaurant design qualified as being inherently distinctive such that the plaintiff need not prove secondary meaning. The Seabrook Test: 1. Is the product packaging and design of common basic shape or design, or is it unique or unusual in a particular field? 2. Is the design a mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known form of ornamentation for a particular class of goods viewed by the public as a dress or ornamentation for such goods. Why Miller’s Ale House Failed The court concluded in applying this test that the design, shape and combination of elements claimed by the plaintiff was not so unique, unusual or unexpected that it could be perceived automatically as an indicator of origin and thus a trademark. It affirmed summary judgment on that ground. Seabrook Will Work For Product Design Infringement Miller’s Ale House also recognized, based on the language in Wal-Mart, that the Seabrook test may not be suitable for evaluating product design cases in which secondary meaning must always be established in order to establish protection. Miller’s Ale House, 702 F.3d 1323, citing Wal-Mart at 529 U.S. 213-14. Proving The Necessary Secondary Meaning • In a product design case, the first question is whether the design qualifies as packaging or as a product. If the design qualifies as a product, secondary meaning must be established. • An illustrative case is Fedders Corp. v. Elite Classics, 268 F. Supp. 2d 1051 (S.D. Ill. 2003). In that case the plaintiff, an air conditioning manufacturer, claimed the defendant’s competing product was a virtual copy of the plaintiff’s air conditioner and claimed trade dress in the curved design on the decorative front of the air conditioner, described sometimes as an undulating curve. The court held that the undulating curve would not qualify as packaging, but rather product design. • The court went on to note that the curve or undulating design was not functional in the typical utilitarian sense, but it did serve the purpose of making the air conditioner more aesthetically appealing. Because it was designed for aesthetics, it qualified as nonfunctional under TrafFix. (The Court noted that functionality is not the test since the component, if functional, would not be protectable at all because there is no protection for a functional component.) • Is this protecting against confusion or merely hurting an innovator? More On Proving Secondary Meaning • To qualify as protectable trade dress in this context, the plaintiff was required to show that in the minds of the consuming product the primary significance of the undulating curve on the line of air conditioners in question “is to identify Fedders as the maker.” 268 F. Supp. 2d at 1062. In order to meet this burden, plaintiff had to establish through direct consumer testimony, or consumer surveys, or proof of length and manner of use, length and manner of advertising and sales and other factors such as intentional copying. Id. In re Joanne Slokevage 441 F.3d 957 (Fed. Cir. 2006) In this case, a trade mark applicant was refused registration of a product configuration consisting of a foldable fold of the area of the rear pockets on a pair of pants. The Trademark Trial and Appeals Board determined the trade dress was product design, and thus did not qualify as inherently distinctive under Wal-Mart. • “Just as the product design in Wal-Mart consisted of certain design features featured on clothing, Slokevage’s trade dress similarly consisted of design features, holes and flaps, featured in clothing, revealing the similarity between the two types of design.” • As in Wal-Mart the product design serves the purpose of making the product itself more appealing and is thus aesthetic in its basic function. Thus consumers may purchase the clothing for its utilitarian purpose or because they find the appearance of the garment desirable. And consistent with the opinion of Wal-Mart, in such cases where the purchase implicates a utilitarian or aesthetic purpose, rather than a source identifying function, it is appropriate to require proof of acquired distinctiveness. 441 F.3d at 962. The Role of Functionality In Trade Dress Infringement • “The person who asserts trade dress protection has the burden of proving that the matter sought to be protected is not functional.” (Section 42(a)(3). • Non-functionality is the logical threshold factor. • Dippin’ Dots, Inc. v. Frosty Bites Distribution, LLC., 369 F.3d 1197, 1202 (11th Cir. 2004) (remarking that because plaintiff had not “met its burden of establishing the non-functionality of its product design, we decline to address the other two elements of the claim.”) • The court further concluded that the defendant’s “usurpation of DDI’s business may have been immoral or unethical” but it was “not illegal.” (The company went bankrupt). Functionality/Nonfunctionality Question It is essential to a claim of trade dress infringement that the plaintiff establish that the trade dress is primarily nonfunctional. Epic Metals Corp. v. Souliere, 99 F.3d 1034 (11th Cir. 1996). The issue of functionality is a question of fact. In general, if a design “enables a product to operate or improves on a substitute design in some way (such as by making the product cheaper, faster, lighter or stronger), then the design cannot be trademarked.” Jay Franco & Sons, Inc. v. Franek, 615 F.3d 855, 857 (7th Cir. 2010) (Judge Easterbrook). Supreme Court Test for Functionality “In general terms, a product feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article.” Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844, n. 10 (1982). This has become known as the “traditional test.” In the Qualitex decision, however, the Supreme Court also stated that a feature is functional if “exclusive use of the feature would put competitors at a significant nonreputational-related disadvantage. Qualitex, 514 U.S. 159 (1995). This is sometimes called the “competitive necessity test.” If the design in question is functional under the traditional test, “there is no need to proceed further to consider if there is a competitive necessity for the feature.” Qualitext, 514 U.S. at 165. The customary traditional test factors: 1. The existence of a utility patent, which discloses the utilitarian advantages of the design. 2. Advertising or promoting the utilitarian advantages of the design 3. The existence of alternative designs which perform the utility function as well. 4. Whether or not the design results from cheap or a superior method of manufacturing the article (In re Morton-Norwich Products, Inc., 671 F.2d 1332 (C.C.P.A. 1982)). Other Rules for Determining Functional vs. Nonfunctional Features Lanham Act Section 2(e), 15 U.S.C. §1091(c), forbids registration of any matter that is as a whole functional. This statute requires a consideration of the functionality of a combination of parts as opposed to any particular part in the claim combination. A design patent may actually support the existence of nonfunctional trade dress attributes in the product design, since the design patent is granted only for nonfunctional designs. Illustrative Cases in the 11th Circuit • Epic Metals: In this case the plaintiff claimed a trade dress in a nonpatented sheet steel deck profile involving a dovetail configuration claimed to be primarily nonfunctional. The court noted the following factors were important in determining whether the dovetail configuration qualified as primarily nonfunctional: Epic Metals A. Does the dovetail configuration affect plaintiff’s cost or quality? B. Would free competition be hindered from protection of the dovetail configuration, because there are only a limited number of other options available? The Court concluded that the claimed trade dress was functional and had been admitted as such by the plaintiff. Particularly compelling were advertisements the plaintiff used to promote the functional aspects of its deck profile and geometric configurations. Dynamic Designs Distrib. v. Nalin Mfg., LLC 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 54217 (M.D. Fla. April 18, 2014) Plaintiff claimed a trade dress in an after market speaker adapter made of steel having rounded corners and featuring holes for mounting, including hardware for installation. The court cited Qualitex: the functionality doctrine prevents trademark law which seeks to promote competition by protecting a firm’s reputation, from instead inhibiting legitimate competition by allowing a producer to control a useful product feature. Id. at *10, quoting from Qualitex at 514 U.S. 164. Pride Family Brands, Inc. v. Carl’s Patio West, Inc., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 11799 (S.D. Fla. Jan. 29, 2014) Finding as functional the claimed elements of patio furniture in rejecting any emphasis on the copying of those elements by the Defendant. Competitive Necessity and Aesthetic Functionality • Qualitex: – Recognized aesthetic functionality and quoted from the Restatement (Third) of Unfair Competition: a design is functional when its aesthetic value confers a “ a significant benefit that cannot be duplicated by the use of alternative designs.” 514 U.S.170 – The Court also notes that “lower courts have permitted competitors to copy the green color of farm machinery (because customers wanted their farm equipment to match) and have barred the use of black as a trademark on outboard boat motors (because black has the special functional attributes of decreasing the apparent size of the motor and ensuring compatibility with many different boat colors).” Id. – Under this approach a design is aesthetically functional where legal protection of the design would significantly hinder competitors from competing in the relevant product market or submarket because of its aesthetic value Dippin’ Dots and Aesthetic Functionality in the 11th Cir. • The Court held that the color, shape, and size of Dippin’ dots were aesthetic functions “that easily satisfy the competitive necessity test because precluding competitors . . .from copying any of these aspects of Dippin’ dots would eliminate all competitors in the flash-frozen ice cream market, which would be the ultimate non-reputation-related disadvantage. See TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 32-33.” Dippin Dots, 369 F.3d 1204 n. 7. • The Court held that the relevant market was the plaintiff’s particular market as well: the defendants “wants to compete in the flash-frozen ice cream business, which is in a different market from more traditional forms of ice cream.” Id. What Are the Limits to The Aesthetic Functionality Defense? • In Dippin’ Dots, there is an assumption that the innovator in a new product “market” may be required to accommodate direct competition in that market, if there is no patent protection for its design and if the product incorporates elements that confer on the innovator a non-reputationrelated advantage, such as using colors associated with flavors or sizes or shapes which are naturally more pleasing to the consumer or have superior characteristics. • There are, however, limits to this argument: – “If the feature or combination of features in the copied design merely enable the “second-comer” to “market his product more effectively, it is entitled to protection.” But not so if the feature must be slavishly copied in order for competition to be possible at all. OraLabs, Inc. v. The Kind Grp., LLC, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 98246 (D. Colo. July 28, 2015). Limits to Aesthetic Functionality Continued • Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am. Holding, Inc., 696 F.3d 206, 222(2d Cir. 2012): If the trade dress incorporates distinctive and arbitrary arrangements of predominantly ornamental features that do not hinder potential competitors from entering the same market with differently dressed versions of the product, then they are nonfunctional and eligible for protection. • Brunswick Corp. v. Spinit Reel Co., 832 F.2d 513, 519 (10th Cir. 1987): Determining whether a design is aesthetically functional rests on “whether alternative appealing designs or presentations of the product can be developed.” (Also noting the need to protect from monopolizing designs while also “protecting a producer who takes the initiative” to innovate). An Evolving Split in the Circuits On Aesthetic Functionality • TrafFix can be interpreted as eliminating the existence of alternatives in the functionality determination. Compare Jay Franco & Sons, Inc. v. Franek, 615 F.3d 855, 857 (7th Cir. 2010) (trade dress is functional even if there are alternative designs if the consumer “would pay to have it rather than be indifferent toward or pay to avoid it”) with Valu Eng’g, Inc. v. Rexnord Corp., 278 F.3d 1268, 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2002) and McAirlaids, Inc. v. Kimberly-Clark Corp., 756 F.3d 307, 312 (4th Cir. 2014) availability of alternative designs remains a legitimate source of evidence for determining if a feature is functional). • It is unclear where the Eleventh Circuit stands on this issue after Dippin’ Dots. See Dippin Dots, 369 F.3d 1203-04; R. Bone, Trademark Functionality Reexamined, 7 J. of Legal Analysis 183, 218 (Spring 2015) (lumping Dippin’ into the line of cases rejecting the continued viability of evidence of acceptable alternative designs). Some Illustrative Examples From Zamperla v. Being Jiuhua Amusement Rides, et al • Most of the designs in question are covered by expired or issued utility patents or in some cases design patents • On motion for default, the Court treated the matters as involving knock off or look alike designs • The merits of the claim were never reached since the defaults were upheld even though the judgment for damages was vacated From U.S. Patent 5,791,998 From U.S. Patent 6,022,276 Title From Vekoma’s U.S. Patent Number 8,057,317 Whirlwind Cavalier (BJARM) Title