Word

advertisement

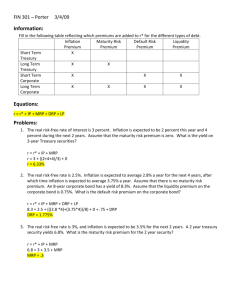

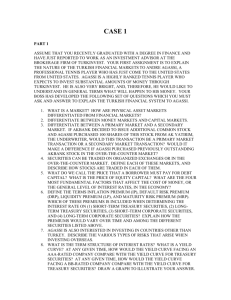

FINA441 - Chapter 3 Notes DEBT VS. EQUITY SECURITIES Investment securities generally come in two forms, debt securities and equity securities. These two forms of securities relate to the right side of the balance sheet (Assets= Liabilities + Owners’ Equity) and are central to how a firm obtains its financing. The essential question is whether the investor loans or owns. COMPONENTS OF RISK: 1. 2. 3. Investment Grade 4. Real Risk-Free Rate (RRFR): Rate that would exist on a riskless investment if zero inflation were expected. Inflation Risk Premium (IRP): the extra return needed to compensate for the risk that rising costs over time will counteract the fixed return on investments (e.g. if you get a 4% fixed rate on your bond yet the cost of living is going up 5% per year, you aren’t keeping up). Interest Rate Risk Premium (IRRP): the extra return needed to compensate for the risk that those who hold investments with long-term fixed rates will see interest rates increase and therefore the attractiveness and price of their investments decrease (e.g. if you get a 4% fixed rate on your bond investment, but rates climb to 6%, you are not a happy camper.) Default Default Risk Premium (DRP): the extra return needed to compensate for the risk that you may not get back some or all of expected cash flows from the investment. Considered very low for U.S. Treasuries (which were recently downgraded by S&P to AA+). Also called Credit Risk Premium. The ratings issued by the agencies are useful indicators of default risk but they are opinions, not guarantees. The Financial Reform Act of 2010 established an Office of Credit Ratings within the SEC to regulate credit rating agencies. Rating agencies must establish internal controls. Non-Invest Grade (Junk) 5. 6. 7. Liquidity Risk Premium (LRP): the extra return needed to compensate for the risk that the investment cannot be converted into cash quickly at a reasonable price. Considered zero for U.S. Treasuries. Taxability Risk Adjustment (TRA): the extra return needed to compensate for the risk of future cash flows being reduced because of taxes (e.g. (e.g. you earned $1000 of interest from your bond investment return; but after the taxman took his hand out of your pocket, you were only left with only $65). After after-tax return equals before-tax return multiplied by (1-tax rate). Interest income from U.S. Treasuries is subject to Federal tax, but not subject to tax in some states. On the other hand, interest from state & local municipal bonds is not subject to Federal tax, but may be subject to tax in some states. Bottom line: the Federal government subsidizes states in their effort to raise funding for state and local infrastructure. Special Features: a. Call premium (CP) feature i. Callable debt enables borrower to pay off debt early at a specified price ii. Exercised when rates drop to a level that makes refinancing worth the cost iii. Lenders demand higher rates on callable bonds because of the re-investment risk they face when they get their money back early and rates have dropped. b. Convertibility feature (CONV) i. Investor has the option to convert debt (bonds) into equity (stocks) ii. This right is attractive to investors, who will thus accept a smaller rate of return FORMULA FOR YIELD ON LONG-TERM, FIXED-RATE DEBT SECURITIES Y = RRFR + IRP +IRRP+ DRP+LRP+/- TR + CP - CONV Where: Y = yield of security RRFR = real risk free rate (yield on short-term Treasury security) IRP = inflation risk premium IRRP = interest-rate risk premium DRP = default risk premium (credit risk) LRP = liquidity risk premium TRA = adjustment for tax status CP = call feature premium CONV = convertibility discount NOTE: IRP, IRRP, CP and CONV are components most applicable to long-term, fixed rate debt. The other components are present in both short-term and long-term debt. DEFINITIONS: U.S. Treasury Bills (T-bills): Obligations of the federal gov’t issued in 3, 6 and 12-month maturities (1-yr maturities have recently been discontinued). Sold at a discount with the return of face value at maturity (zerocoupons). T-bills are considered the most risk-free investment (i.e. very little IP, IRRP, DRP or LRP; may be slight TRP). Treasuries are considered to have zero default risk because they have never defaulted, the Federal gov=t can print money to pay its obligations if necessary, and the Fed is so intricately linked with the overall economy that if it goes down, everything else must have gone down already, e.g. it is the last domino in a falling economy. 2. U.S. Treasury Notes & Bonds: Obligations of the federal gov’t issued in denominations of $1,000 or more and paying semi-annual, fixed, interest (coupons). Notes have maturities 2-10 years, and bonds have maturities greater than 10 years, up to 30 years. Because of their long-term fixed rates, T-notes & bonds have IP and IRRP, but little DRP or LRP. 3. Municipal Bonds (Muni’s): Obligations of state and local gov’ts, generally having fixed interest rates, with maturities up to 30 years. Income is exempt from Federal income tax, although there may be a slight tax at the state level; so there could be a small TRP. Because of their long-term fixed rates, muni’s have IP and IRRP. Also because state and local gov’ts cannot print money and go bankrupt, muni’s can have considerable DRP (e.g. Orange County, CA; Vallejo, CA; Harrisburg, PN). Since muni’s aren’t traded as much as U.S. Treasuries, they may some LRP. 4. Preferred Stocks: Any dividends must be paid first to preferred stockholders, and unpaid dividends must usually be made-up (cumulative). In return, preferred stockholders forfeit their right to vote. Because dividends are not taxable to corporate investors, they own much of the preferred stock in the U.S. Risks of preferred stock include DRP, LRP, and some TRP (for individual investors). 5. Investment-Grade Corporate Bonds: Bonds of large, well-managed corporations with a history of strong growth and earnings. Risks are similar to T-bonds except there can be DRP and maybe a tad of LRP. 6. Blue Chip Common Stocks: Stocks of large, long-established corporations with a history of strong growth and earnings. Risks include significant DRP. Often considered a hedge against IP. 7. Junk Bonds: Low-quality bonds rated below investment-grade. Often associated with start-ups firms, firms lacking a track record, firms with an excessive debt or weak earnings record, etc. Used extensively in the eighties for leveraged-buyouts (LBOs), restructuring, expansion . . . until the collapse of the junk bond market in the late eighties, due in part to recession fears and the trading scandals of Michael Milken, Ivan Boesky and friends. Risks are similar to investment-grade bonds, except there is considerably more DRP. 8. Real Estate: Investment in land and income-producing real property -- typically offers solid returns over long periods of time. Includes some DRP and a lot of LRP. Often considered a hedge against IP. 9. Small Stocks: Common stocks of smaller, more speculative corporations. Similar risks to blue-chip stocks except considerably more DRP and LRP. 10. Penny Stocks: Common stocks, often selling for less than a dollar, that offer the possibility of huge returns if successful, but also the risk of complete loss. Significant DRP and LRP. 1. TREASURY SECURITIES AND U.S. DEBT Types of Treasury Securities: Bill Note Bond < 1 yr (4,13 & 26 & 52 weeks) > 1yr, <= 10 yrs (2,3,5 & 10 yrs) > 10 yrs, <= 30 yrs Zero interest payments Semi-annual interest payments Semi-annual interest payments Issued < face (at a discount) Issued at face Issued at face Little default, int. rate, or liquidity risk Little default or liquidity risk Little default or liquidity risk Fairly New: Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), for which principal increases by inflation TERM STRUCTURE OF INTEREST RATES Refers primarily to Treasury securities (T-Bills, Notes and Bonds) which are similar in all ways except their maturity. In other words, they have identical default risk (backed by the same government), identical liquidity risk (essentially zero, since they can all be sold in a matter of minutes), identical taxability risk, identical call features, and no convertibility feature. Which leaves only one characteristic that is difference between these securities, and that is their maturity. Long-term bonds have rates fixed for many decades or years. This causes more inflation risk and interest-rate risk than in short-term bills, whose rates may be only fixed for weeks or months. This relationship is illustrated in the graphs below. See Living Yield Curve at http://www.smartmoney.com/investing/bonds/the-living-yield-curve-7923/ (this requires that your browser’s security system activate Java). See also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yph8TRldW6k Notice on the graph above how default risk for Baa rated bonds climbs substantially during recessions. 1. Historical review of the term structure (refer, in part, to graph above) a. Growing economies generally have a normal or steep upward sloping curve; prior to low or negative economic growth, the curve is usually inverted or flat. b. Early 1980s downward sloping yield curve c. 1982 to 1999: an upward sloping yield curve generally persisted d. 1999: inverted curve e. Sept. 11, 2001: investors shifted funds into short-term securities and the Fed provided funds to the banking system, causing the yield curve to become steeper f. 2002-2006: generally a normal yield curve, but with rates very low g. 2007: curve shifted to inverted shape h. 2008: flight to safety caused S/T yields to approach zero. i. 2009-2011: investors willing to seek greater risk and expectations of future growth and inflation increase 2. 3. 4. 5. spread. Impact of Federal debt management on term structure a. If the Treasury uses a relatively large proportion of long-term debt, this places upward pressure on longterm yields, since this creates demand for long-term funding b. If the Treasury uses short-term debt, long-term interest rates may be relatively low Uses of the term structure a. Forecast interest rates b. Forecast recessions c. Investment and financing decisions i. Lenders/borrowers attempt to time investment/financing based on expectations shown by the yield curve ii. Riding the yield curve involves investment in higher-yielding long-term securities with short-term time horizons d. Timing of bond issuance Theories of Term Structure a. Pure Expectations Theory i. Long-term rates reflect expected future short-term rates ii. Yield curve slope reflects market expectations of future interest rates compared to current rates iii. Assumes investor has no maturity preferences and transaction costs are low b. Liquidity Premium Theory i. Investors prefer short-term, more liquid, securities that do not lock in interest rates for long periods of time ii. Long-term securities have more interest rate risk from locking into a fixed rate for long periods iii. Investors will demand a premium (higher return) to compensate for the liquidity/interest rate risk of long-term securities c. Segmented Markets Theory i. Theory explaining segmented, broken yield curves ii. Assumes investors have maturity preference, e.g., short-term vs. long-term maturities, which is independent of their future rate expectations 1. Pension funds and life insurance companies prefer long-term investments 2. Commercial banks prefer short-term investments 3. Senior business majors saving for grad school vs. retirement iii. Explains why rates and prices can vary significantly between certain maturities Yield differences between countries are related to: a. Expected changes in foreign exchange rates b. Varied expected real rates of return c. Varied expected inflation rates d. Varied country and business risk e. Varied central bank monetary policy f. Interest rate movements across countries tend to be positively correlated. For charts of various US debt and deficit figures, see http://www.usgovernmentdebt.us For sovereign debts as percent of GDP by country, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_public_debt For major foreign holders of US Debt, see http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Documents/mfh.txt