Student 2 Mr. Cowherd Modern World History, Period 6 February 26

advertisement

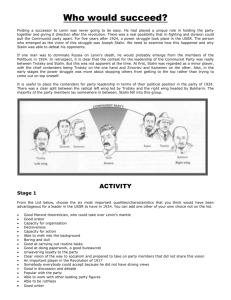

Student 2 Mr. Cowherd Modern World History, Period 6 February 26, 2013 The Evolution of Soviet Communist Ideology During the history of a philosophy, its ideas inevitably change as it is spread among a group of people. Each person interprets the philosophy differently, informed by their personal experience and interests. Christianity today, with billions of followers listening to elaborate religious music and decorating Christmas trees, would likely seem totally foreign to Christians of the first century CE. Bolshevik and Communist philosophy went in the same direction. As Russia and the Soviet Union went through the period of industrialization and collectivization during Stalin’s rule, its governing philosophy strayed from Lenin’s original values of to fit the desires of those in power. Lenin’s philosophy stressed the idea that Bolsheviks needed allies to assist them in their creation of the world’s first socialist country. The working class in a society that has recently removed the political influence of the bourgeoisie “remains for a long time weaker than the bourgeoisie,” writes Lenin. It is “obligatory” for the communist leaders to try to “[win] a mass ally” in order to defend themselves from the hostile bourgeoisie, even if this ally does not share their beliefs (“Left-Wing Communism”). This was used by Lenin to justify his cooperation with capitalism during the period of the New Economic Policy beginning in 1921, and to promote tolerance of slight differences in viewpoint among fellow communists. When Stalin came to power, though, he stated that “liberalism in the attitude towards Trotskyism,” a faction within the party, “is blockheadedness bordering on crime,” (“Some Questions”). Stalin changed official communist policy from alliance with people who had similar goals to a situation where the communist party claimed control over the entire government and economy of the Soviet Union, and its leader’s positions on government issues were the only ones permitted. Stalin changed the official communist philosophy to support the actions he took during the 1920s and 30s to eliminate Trotsky and other communists with whom he did not agree (“Some Questions”). This marks an important point in the development of Soviet totalitarianism: if members of the sole ruling party are prohibited from expressing dissent, then there is nobody left in the government to defend the people’s interests against those who are in power. Another area in which Stalin and his contemporaries strayed from Lenin’s philosophy was their opinion on the timeframe required for the Soviet Union’s development of a totally socialist economy. Lenin believed that a period of capitalism is “advantageous and necessary in an extremely devastated and backward small-peasant country” as a step on the path toward complete socialism (“Left-Wing Communism”). This belief was demonstrated in the New Economic Policy. Stalin, though, believed that full socialism could be accomplished within a short time with the government’s help. He proposed to “develop industry at a rapid rate” and “organize the peasantry into co-operatives on a mass scale” to immediately defeat all forms of capitalism in the Soviet Union (“Some Questions”). Lenin intended the Soviet Union to gradually progress toward socialism with the support of its citizens, while Stalin intended to use the state apparatus to force the working classes to accept his version of socialism. However, Stalin’s toxic combination of collectivization of agriculture and overly rapid industrialization decreased the food supply by making peasants angry and disinclined to work, while also increasing food demand. His choices killed more than three million peasants in the Ukraine alone (Famine-Genocide of 1932-3). Later communists most greatly diverged from Lenin in their ideas about humility and sincerity. In his last written work, “Better Fewer, but Better,” Lenin writes about how communists should “show sound skepticism for too rapid progress” and “boastfulness”, while always being willing to learn from their mistakes. Only this would allow the development of an efficient and competent government that could create true socialism. Less than ten years after his death, though, Stalin stated rather confidently that workers had no uncertainty about the future at a time when the Central Party committee advised that workers who did not show up to work one day should be fired and have their apartments confiscated (Kalinin). Even more bizarrely, Stalin claimed in 1932 that “impoverishment and pauperism in the countryside have been done away with,” the same year that millions of peasants died of starvation (“The Results”). This is not only boastfulness, but false boastfulness, going completely against Lenin’s advice. Though Lenin left many documents detailing his beliefs when he died, the vast majority of his principles were pushed aside by later communists, because of changing times and political expedience. Lenin lived in a country with little industry and many small peasant farms. He believed in a slow transition from capitalism to socialism, the alliance of the communist party with people of other political beliefs and entrepreneurs for mutual benefit, and humility and sincerity as core communist values (“Better Fewer”). After Lenin’s death, Stalin and those who worked with him refused to apply these ideals, instead making the party free of dissent, fighting to make the country industrialize rapidly, and being boastful and self-congratulatory in order to increase their political power and fool the populace into thinking that the country was well-run. In general, people use philosophy to support and justify their actions for ulterior motives. If a philosophy, like Leninism, does not suit its believers, they will change it until it does. People are selfish creatures. Works Cited: "Famine-Genocide of 1932-3." Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, n.d. Web. 23 Feb. 2013. <http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp/ linkpath=pagesFAFamine6Genocideof1932hD73.htm>. Kalinin, M., V. Molotov, and A. Enukidze. "On Firing for Unexcused Absenteeism." Cyberussr.com. Hugo S. Cunningham, 27 Dec. 2000. Web. 24 Feb. 2013. <http://www.cyberussr.com/rus/trud-uvol32-e.html>. Lenin, Vladimir I. "Better Fewer, But Better." Marxists Internet Archive. Trans. David Skvirsky and George Hanna. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013. <http://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1923/mar/02.htm>. Lenin, Vadimir I. "Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder." Marxists Internet Archive. Trans. Julius Katzer. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Feb. 2013. <http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/index.htm>. Stalin, J. V. "Some Questions Concerning the History of Bolshevism." Marxists Internet Archive. Trans. Salil Sen. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013. <http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1931/x01/x01.htm>. Stalin, J. V. "The Results of the First Five-Year Plan." Marxists Internet Archive. Trans. Salil Sen. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013. <http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1933/01/07.htm>. Lenin, Vladimir I. "Third Congress Of The Communist International[1]." Marxists Internet Archive. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2013.