DKA and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar

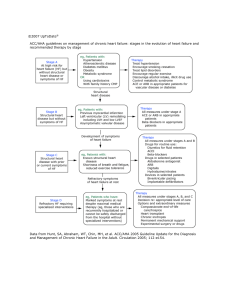

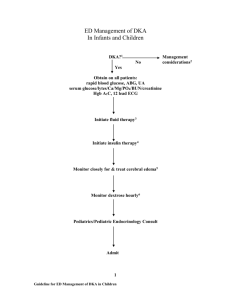

advertisement

DKA: Critical Care Lecture Series PICU Fellows Lecture Objectives Review of the pathophysiology of DKA Review of Fluid Management Current DKA Management Guidelines Review of Common complications Current Protocols Biochemical criteria Hyperglycemia ~200mg/dL Venous pH<7.3 or bicarbonate <15 Ketonemia and ketonuria Pathophysiology Steel, S. 2 1 3 1 2 HHS vs DKA Kitabchi, A., Et Al. Comparing DKA And HHS DKA Hyperglycemia ~200mg/dL Venous pH<7.3 or bicarbonate <15 Ketonemia and ketonuria HHS Glucose >600 pH>7.3 Bicarbonate>15 Small ketonuria Effective serum osmolarity >330mOsom Stupor or coma Clinical Manifestations Dehydration Rapid, deep sighing (Kussmaul respirations) Nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain Progressive obtundation and loss of consciousness Increased leukocyte count with Left shift Non-specific elevation of serum amylase Fever only when infection is present Severity of DKA Mild: Venous pH <7.3 or bicarbonate <15mmol/L Moderate: Venous pH <7.2, bicarbonate <10 Severe: Venous pH <7.1, bicarbonate <5mmol/L Stamatis P, Et al. Frequency of DKA More common at diagnosis in younger children Families who do not have access to medical care Risk is increased in patients with: Poor metabolic control, and previous DKA Peripubertal and adolescent girls Children with psychiatric disorders Children with difficult family situations Children who omit insulin Insulin pump therapy Clinical Assessment Assess the Fluid Status Assess the degree of consciousness Challenges in the ER Accurate fluid assessment of these children is difficult Urine OP is obscured Inevitably tachycardic Kussmal respirations History of the type of fluid to rehydrate is extremely important as well Prospective consecutive case series Percentage loss of weight Parents weight at presentation, inpatient discharge, and first follow-up clinic visit were used to calculate percent loss of body weight 33 episodes of DKA Patients had moderate DKA 4-8% 67% of patients in their study were assessed to be severely dehydrated when only 12% , using percent loss of body weight Biochemical Assessment Obtain plasma glucose, electrolytes, osmolarity, venous pH, pCO2, calcium, phosphorus and Magnesium, HbA1C, CBC UA B-hydroxybutyrate Potassium Cultures Goals of Therapy Correct Dehydration Correct acidosis and reverse ketosis Restore blood glucose to near normal Avoid complications of therapy Identify and treat precipitating event Retrospective cohort study Use of rehydration fluids with higher sodium content would positively influence natremia possibly reducing the incidence and severity of cerebral edema Found that increases in sodium were an independent predicting factor against brain edema Issues: Hypernatremia, change to hypotonic fluids hours after admission Initial Fluid Management Wolfsdorf et al. Fluids Replace deficit for next 4-6 hours with NS or LR Can change fluids to ½ NS or a fluid of greater tonicity if the physician deems this necessary The goal is then to rehydrate evenly over 48 hours Extremely common during treatment Two PICUs, Liverpool and London Retrospective Chart review Incidence of hyperchloremia increased from 6% to 94% over 20 hours of treatment Base deficit decreased over treatment time however proportion due to hyperchloremia increased from 2-98% An Example Calculation.. Body weight in kilograms Establish extent of dehydration Infants Children Mild: 5% = 50 ml/kg 3% = 30 ml/kg Moderate:10% = 100 ml/kg 6% = 60 ml/kg Severe: 15% = 150 ml/kg 9% = 90 ml/kg An Example Calculation Calculate maintenance fluid requirements for the next 48 hours: 200 ml/kg for the first 10 kg body weight + 100 ml/kg for the next 10 kg + 40 ml/kg for the remaining kg Calculate the total amount of fluid to be given for our patient over the next 48 hours More Fluid Calculations… Maintenance plus your deficit will equal what you need to give over 48 hours Divide that number by 48 hours Two Bag Method Metzger DL. Two Bag Method Glucose > 350 mg/dl: Run NS + additives at 100% of calculated rate Glucose 250 – 350 mg/dl: Run NS at 50% rate, run D10 NS at 50% rate Glucose < 250 mg/dl: Run D10 NS + additives at 100% rate Insulin therapy To be started after our initial fluids after the first 1-2 hours in DKA If given before this it has been shown in a case control study in the UK to have a 12 fold increased risk of cerebral edema Dose: 0.1 unit/kg/hour Woldfsdorf, J. Et Al. 20 episodes of DKA in 19 children Bolus group and no bolus group Significantly lowers glucose in first hour “osmotic disequilibrium” Precipitous drop in blood glucose Fort, P. Et al. 38 children with 56 episodes of DKA No statistically significant different change in serum glucose, osmolarity Potassium Total body potassium deficits Major losses from the Intracellular space May be normal on presentation Potassium Hypokalemic Normal potassium Hyperkalemic Woldfsdorf, J. Et Al. Acidosis Severe acidosis reversible by fluid and insulin replacement Stops further ketoacid production Allows ketoacids to be metabolized Bicarbonate administration may cause paradoxical CNS acidosis(Hale, Pj., Et Al.) Retrospective consecutive case series Initial pH < 7.15, Glucose >300 106 children in 16 yr time period, at tertiary university medical centers 57 treated with bicarb No improved clinical outcome with adjunctive bicarbonate therapy Possible longer hospitalization for the patients who received the bicarb Green, SM. Et al. Mortality and Morbidity Cerebral edema accounts for 75-87% of all DKA deaths(Nichols, D. Et Al.) 10-25% have significant residual morbidity Other complications Electrolyte abnormalities DIC, Dural Sinus Thrombosis Sepsis Carlotti A P C P et al. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:170-173 Late risk factors for the development of cerebral oedema. Carlotti A P C P et al. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:170-173 2001, multicenter study Children <18 yr 61 children with CE 181 randomly selected with DKA 174 match to the CE group Using logistic regression, they found that lower CO2 and higher BUN, and children treated with bicarbonate Glaser, Nicole, Et al. Cerebral Edema Diagnostic criteria Abnormal motor or verbal response to pain Decorticate or decerebrate posture Cranial nerve palsy Abnormal neurogenic respiratory pattern o Cerebral edema Major Altered mentation/fluctuatin g level of consciousness Sustained heart rate deceleration-not from improved volume or sleep Age inappropriate incontinence Minor Vomiting Headache Lethargy or difficult to rouse Diastolic blood pressure >90mmHg Age <5yrs One diagnostic, Two major, or one major and one minor have a sensitivity of 92% Treatment of cerebral edema Reduce fluid volume by 1/3 Mannitol 0.5-1gm/kg Hypertonic saline 5-10ml/kg (alternative or second line therapy) Intubation if impending respiratory failure, aggressive hyperventilation Elevate the head of the bed Then---CT to rule out thrombosis or other intracerebral causes Retrospective Observational study, in Royal Children’s Hospital In Melbourne 67 children with DKA Were in two groups equally distributed Plasma osmolarity had a more gradual reduction in the 0.05u/kg/hr group Younger children Further research as whether this may reduce the risk of cerebral edema Hanshi, S, Et Al.l Protocolized approach Minimizes risks for young children with DKA especially for Cerebral Edema ISPAD guidelines are currently the gold standards internationally Woldfsdorf, J. Et Al. Protocols, protocols, protocols…. Additional Protocols Nursing Flowsheets Consensus Statements In Summary Caution use of Hypotonic fluids in the first 12-24 hours of DKA management Assess the ECF contraction Increased attention to serum sodium levels and Chloride levels Delay in the introduction of insulin infusions Protocols Thank you! Any Questions? References British Columbia DKA Toolkit. January 8, 2010. Cefalu W. Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Critical Care Clinics 7(1): 89-108, 1991. Carlotti A P C P et al. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:170-173 Jeha, G, Et al. Treatment and Complication of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in children. Uptodate. September 2010. Kawamata,,T, Et At. Tissue Hyperosmolality and Brain Edema in Cerebral Contusion. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(5):E5 © 2007 American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Kitabchi, A. Et Al. Hyperglycemic Crices In Patients with diabetes: DIiabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA), and Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State. 2007. Fort, P., Et Al. Low Dose insulin infusion in the the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis: bolus versus no bolus. The journal of Pediatrics. January 1980. Glaser, Nicole, Et al. Risk Factors for Cerebral Edema in Children with Diabetic Ketoacidosis. NEJM. Volume 344, No. 4, Jan. 25, 2001. Green SM., Et Al. Failure of Adjunctive Bicarbonate to improve outcome in severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis Ann Emerg Med. 1998 Jan: 31(1): 41-8. . Hale PJ, Crase J, Nattrass M. Metabolic effects of bicarbonate in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Oct 20: 289(6451): 1035 – 8. Hanshi, S, Et Al. Insulin infusion at 0.05 versus 0.1 unit/kg/hr in children admitted to intensive care with diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2011 Vol 12, no 2. 137-140. References Metzger, D. Diabetic Ketoacidosis in children and adolescents: an update and revised treatment protocol. BC Medical Journal. Vol. 52. no 1, Jan/Feb 2010. Nicols, D. Disorders of glucose homeostasis. Rogers’ Textbook of Pediatric Intensive Care. 2008 : 1599-1614. Orlowski, james., Et al. Diabetic Ketoacidosis in the Pediatric ICU. Pediatric Clin N Am 55 (2008) 577-587. Steel, S., Et al. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain (2009) 9 (6): 194-199. doi: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkp034 Taylor, D., Et Al. The influence of hyperchloraemia on acid base interpretation in diabetic ketoacidosis. Intensive Care medicine. (2006) 32:295-301. Toledo, J., Et al. Sodium Concentration in rehydration Fluids for children with ketoacidotic Diabetes: Effect on serum Sodium Concentration. J Pediatr 2009;154:895-900. Woldfsdorf, J. Et Al. Diabetic Ketoacidosis in children and Adolescents with Diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2009:10(suppl. 12): 118-113. Zeitler, P. Et al. Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Syndrome in Children: Pathophysiological Considerations and suggested guidelines for treatment. The Journal of Pediatrics. Vol 158, P9- 14. January 2011.