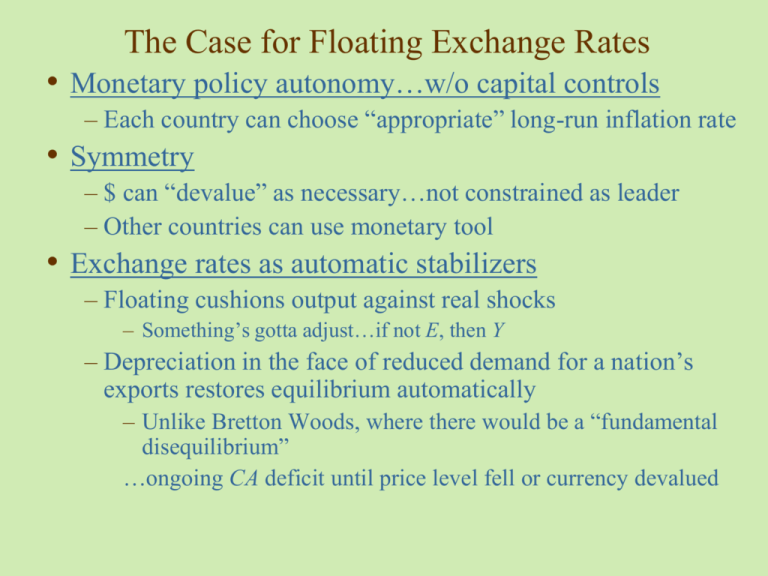

Exchange rates as automatic stabilizers

advertisement

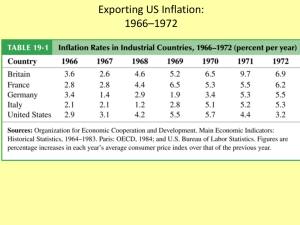

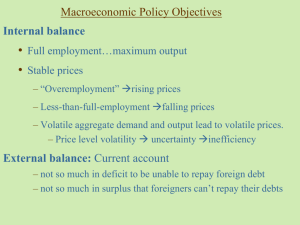

The Case for Floating Exchange Rates • Monetary policy autonomy…w/o capital controls – Each country can choose “appropriate” long-run inflation rate • Symmetry – $ can “devalue” as necessary…not constrained as leader – Other countries can use monetary tool • Exchange rates as automatic stabilizers – Floating cushions output against real shocks – Something’s gotta adjust…if not E, then Y – Depreciation in the face of reduced demand for a nation’s exports restores equilibrium automatically – Unlike Bretton Woods, where there would be a “fundamental disequilibrium” …ongoing CA deficit until price level fell or currency devalued The Case for Floating Exchange Rates Effects of a Temporary Fall in Export Demand Exchange rate, E DD2 DD1 2 E2 (a) Floating exchange rate 1 E1 Depreciation leads to higher demand for and output of domestic products AA1 Y2 Y1 Exchange rate, E Output, Y DD2 DD1 (b) Fixed 1 exchange rate E 3 1 AA2 Y3 Y2 Y1 Fixed exchange rates mean output falls as much as the initial fall in aggregate demand AA1 Output, Y The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Lack of discipline • … but a floating exchange rate bottles up inflation in a country whose government is “misbehaving”. Destabilizing speculation • Hot money …but “fundamental disequilibrium” one-way bet under fixed rates • Countries can be caught in a “vicious circle” of depreciation and inflation. E Pim CoL W P E • Floating exchange rates make a country more vulnerable to money market disturbances. – Fixed rates cushion output against monetary shocks L M nothing shifts under fixed rates The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates A Rise in Money Demand Under a Floating Exchange Rate Exchange rate, E DD 1 E1 2 E2 AA1 AA2 Y2 Y1 Output, Y The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Injury to International Trade and Investment • Exporters and importers face greater exchange risk. – But forward markets can protect traders against foreign exchange risk. • International investments face greater uncertainty about payoffs denominated in home country currency. Uncoordinated Economic Policies • Countries can engage in competitive currency depreciations. …under Bretton Woods, policies “coordinated” via US privilege • A large country’s fiscal and monetary policies affect other economies …aggregate demand, output, and prices become more volatile across countries if policies diverge. Free Float Really Managed Float • Fear of depreciation – inflation spiral intervention The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates • Speculation and volatility in the foreign exchange market • If traders expect a currency to depreciate in the short run, they may quickly sell the currency to make a profit, even if it is not expected to depreciate in the long run. • Expectations of depreciation lead to actual depreciation in the short run. • The assumption we’ve been using that expectations do not change when temporary economic changes occur is not valid if expectations change quickly in anticipation of even temporary economic changes. • In fact, exchange rate volatility has increased since 1973 Macroeconomic Data for Key Industrial Regions, 1963–2006 The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Floating and Discipline: Inflation Rates in Major Industrialized Countries, 1973-1980 (percent per year) Nominal and Real Effective Dollar Exchange Rate Indexes, 1975–2006 Purchasing Power Parity??? Source: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Studies. Due to contractionary monetary policy and expansive fiscal policy in the U.S., the dollar appreciated by about 50% relative to 15 currencies from 1980–1985. – This contributed to a growing US current account deficit Countries then engaged in 2 major efforts to influence exchange rates: • The 1985 Plaza Accord reduced the value of the dollar relative to other major currencies… “bringing down dollar” • The 1987 Louvre Accord: intended to stabilize exchange rates – Specified zones of +/- 5% around which current exchange rates were allowed to fluctuate. – Quickly abandoned – The October 1987 stock market crash made production, employment and price stability the primary goals for the U.S. central bank exchange rate stability became less important. – New targets were (secretly) made after October 1987, but central banks had abandoned these targets by the early 1990s. Macroeconomic Interdependence Under Floating Rate The Large Country Case • Effect of a permanent monetary expansion by Home – Home’s currency depreciates, Home output rises – Foreign output may rise or fall. – Foreign’s currency appreciates Foreign’s output falls – Home’s economy expands Foreign sells more to Home • Effect of a permanent fiscal expansion by Home – Home output rises, Home’s currency appreciates – Foreign output rises – Foreign’s currency depreciates Foreign’s output rises – Home’s economy expands Foreign sells more to Home Macroeconomic Interdependence Under Floating Rate Unemployment Rates in Major Industrialized Countries, 1978-2000 (percent of civilian labor force) Exchange Rate Trends and Inflation Differentials, 1973–2006 High-inflation countries have tended to have weaker currencies than their low-inflation neighbors. Source: International Monetary Fund and Global Financial Data. Interdependence of “Large” Countries: Rebalancing The U.S. has depended on saved funds from many countries, while it has borrowed heavily. • The U.S. has run a current account deficit for many years due to its low saving and high investment expenditure. As foreign countries spend more and lend less to the U.S., • interest rates may rise • the U.S. dollar will depreciating • the U.S. current account will improve (becoming less negative). Global External Imbalances, 1999–2006 Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2007. 19-15 U.S. Real Interest Rate, 1997–2007 Source: Global Financial Data. Real interest rates are defined as ten-year government bond rates less average inflation over the preceding twelve months. The data are twelve-month moving averages of monthly real interest rates so defined. What Has Been Learned Since 1973? • After 1973 central banks intervened repeatedly in the foreign exchange market to alter currency values. – To stabilize output and the price level when certain disturbances occur – To prevent sharp changes in the international competitiveness of tradable goods sectors • Monetary changes had a much greater short-run effect on the real exchange rate under a floating nominal exchange rate than under a fixed one. • The international monetary system did not become symmetric until after 1973. – Central banks continued to hold dollar reserves and intervene. • The current floating-rate system is similar in some ways to the asymmetric reserve currency system underlying the Bretton Woods arrangements … exorbitant privilege What Has Been Learned Since 1973? The Exchange Rate as an Automatic Stabilizer • Experience with the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 favors floating exchange rates. • The effects of the U.S. fiscal expansion after 1981 provide mixed evidence on the success of floating exchange rates. Discipline • Inflation rates accelerated after 1973 and remained high through the second oil shock. • The system placed fewer obvious restraints on unbalanced fiscal policies. – Example: The high U.S. government budget deficits of the 1980s. What Has Been Learned Since 1973? Destabilizing Speculation • Floating exchange rates have exhibited much more day-today volatility. – The question of whether exchange rate volatility has been excessive is controversial. • In the longer term, exchange rates have roughly reflected fundamental changes in monetary and fiscal policies and not destabilizing speculation. • Experience with floating exchange rates contradicts the idea that arbitrary exchange rate movements can lead to “vicious circles” of inflation and depreciation. International Trade and Investment • For most countries, the extent of their international trade shows a rising trend after the move to floating. Many fixed exchange rate systems have developed since 1973. • European monetary system and euro zone • The Chinese central bank currently fixes the value of its currency. • ASEAN countries have considered a fixed exchange rates and policy coordination.