The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates

advertisement

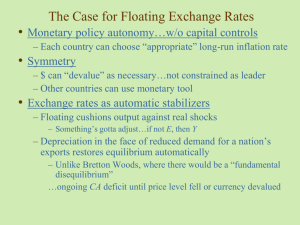

Chapter 19 Macroeconomic Policy and Coordination under Floating Exchange Rates Introduction The floating exchange rate system, in place since 1973, was not well planned before its inception. By the mid-1980s, economists and policymakers had become more skeptical about the benefits of an international monetary system based on floating rates. Why has the performance of floating rates been so disappointing? What direction should reform of the current system take? This chapter compares the macroeconomic policy problems of different exchange rate regimes. The Case for Floating Exchange Rates There are three arguments in favor of floating exchange rates: Monetary Policy Autonomy Floating exchange rates: Restore monetary control to central banks Allow each country to choose its own desired long-run inflation rate Symmetry Monetary policy autonomy Symmetry Exchange rates as automatic stabilizers Floating exchange rates remove two main asymmetries of the Bretton Woods system and allow: Central banks abroad to be able to determine their own domestic money supplies The U.S. to have the same opportunity as other countries to influence its exchange rate against foreign currencies Exchange Rates as Automatic Stabilizers Floating exchange rates quickly eliminate the “fundamental disequilibriums” that had led to parity changes and speculative attacks under fixed rates. The Case for Floating Exchange Rates Monetary Policy Autonomy If banks were no longer obliged to intervene in currency markets to fix exchange rates, governments would be able to use monetary policy to reach internal and external balance. Furthermore, no country would be forced to import inflation (or deflation) from abroad. Symmetry Under a system of floating rates the inherent asymmetry of Bretton Woods would disappear and the United States would no longer be able to set world monetary conditions all by itself. At the same time, the United States would have the same opportunity as other countries to influence its exchange rate against foreign currencies. The Case for Floating Exchange Rates Exchange rates as automatic stabilizer Even in the absence of an active monetary of an active monetary policy, the swift adjustment of market-determined exchange rates would help countries maintain internal and external balance in the face changes in aggregate demand. The long and agonizing periods of speculation preceding exchange rate realignments under the Bretton Woods rules would not occur under floating. Figure 19-1 shows that a temporary fall in a country’s export demand reduces that country’s output more under a fixed rate than a floating rate. The Case for Floating Exchange Rates Figure 19-1: Effects of a Fall in Export Demand Exchange rate, E DD2 DD1 1 (a) Floating exchange rate E1 AA1 Y1 Exchange rate, E Output, Y DD2 DD1 (b) Fixed 1 exchange rate E 3 1 AA2 Y3 Y1 AA1 Output, Y The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates There are five arguments against floating rates: Discipline Destabilizing speculation and money market disturbances Injury to international trade and investment Uncoordinated economic policies The illusion of greater autonomy The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Discipline Floating exchange rates do not provide discipline for central banks. Central banks might embark on inflationary policies (e.g., the German hyperinflation of the 1920s). Central banks freed from the obligation to fix their exchange rates might embark on inflationary policies. In other words, the “discipline” imposed on individual countries by a fixed rate would be lost. The pro-floaters’ response was that a floating exchange rate would bottle up inflationary disturbances within the country whose government was misbehaving. The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Destabilizing Speculation and Money Market Disturbances Floating exchange rates allow destabilizing speculation. Countries can be caught in a “vicious circle” of depreciation and inflation. Advocates of floating rates point out that destabilizing speculators ultimately lose money. Floating exchange rates make a country more vulnerable to money market disturbances. Figure 19-2 illustrates this point. Exchange rate, E DD 1 E1 E2 2 AA1 AA2 Y2 Y1 Speculation on changes in exchange rates could lead to instability in foreign exchange markets, and this instability, in turn, might have negative effects on countries’ internal and external balances. Further, disturbances to the home money market could be more disruptive under floating than under a fixed rate. Output, Y The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Injury to International Trade and Investment Floating rates hurt international trade and investment because they make relative international prices more unpredictable: Exporters and importers face greater exchange risk. International investments face greater uncertainty about their payoffs. Supporters of floating exchange rates argue that forward markets can be used to protect traders against foreign exchange risk. The skeptics replied to this argument by pointing out that forward exchange markets would be expensive. Floating rates would make relative international prices more unpredictable and thus injure international trade and investment. The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Uncoordinated Economic Policies Floating exchange rates leave countries free to engage in competitive currency depreciations. Countries might adopt policies without considering their possible beggar-thy-neighbor aspects. If the Bretton Woods rules on exchange rate adjustment were abandoned, the door would opened to competitive currency practices harmful to the world economy. As happened during the interwar years, countries might adopt policies without considering their possible beggar-thy-neighbor aspects. All countries would suffer as a result. The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates The Illusion of Greater Autonomy Floating exchange rates increase the uncertainty in the economy without really giving macroeconomic policy greater freedom. A currency depreciation raises domestic inflation due to higher wage settlements. Floating exchange rate would not really give countries more autonomy. Changes in exchange rates would have such pervasive macroeconomic effects that central banks would feel compelled to intervene heavily in foreign exchange markets even without a formal commitment to peg. Thus, floating would increase the uncertainty in the economy without really giving macroeconomic policy greater freedom. The Case Against Floating Exchange Rates Inflation Rates in Major Industrialized Countries, 1973-1980 (percent per year) Nominal and Real Effective Dollar Exchange Rates Indexes, 1975-2000 A two-country model of macroeconomic interdependence under a floating rate The model is applied to the short run in which output prices can be assumed to be fixed. Imagine a world of two countries, Home and Foreign. In reality, the level of GNP abroad influences foreign demand for the home country’s exports and therefore the home current account balance. We assume that Home’s current account is a function of the real exchange rate, EP*/P, its own disposable income, Y-T, and Foreign’s disposable income Y*-T*. Home’s current account is therefore CA=CA(EP*/P, Y-T, Y*-T*). A real depreciation of Home’s currency is assumed to cause an increase in its current account balance, while a rise in Home disposable income leads to a fall. A two-country model of macroeconomic interdependence under a floating rate In the model of two interacting economies, a rise in Foreign disposable income raises Foreign spending on Home products, it raises Home exports, therefore causes an increase in Home’s current account balance. Aggregate supply and demand are equal in Home when Y=C(Y-T)+I+G+ CA(EP*/P, Y-T, Y*-T*). Foreign’s current account, CA*, also depends on the relative price of Home and Foreign products, EP*/P, and on disposable income in the two countries. In a world of two countries, Home’s current account surplus must exactly equal Foreign’s current account deficit when both balances are measured in term’s of a common unit. A two-country model of macroeconomic interdependence under a floating rate In terms of Foreign output, Foreign’s current account is CA*=-CA(EP*/P, Y-T, Y*-T*)÷(EP*/P). A rise in Home income, by worsening Home’s current account CA, improves CA*; in the same way, a rise in Foreign income worsens CA*. We assume that a rise in EP*/P(a relative cheapening of Home output) causes CA* to fall at the same time it causes CA to rise. Foreign output market supply equals demand when Y*=C*(Y*-T*)+I*+G*-(P/EP*)×CA(EP*/P, Y-T, Y*-T*). The HH schedule shows the Home and Foreign output levels at which aggregate demand equals aggregate supply in Home. HH slopes upward because a rise in Y* increases Home exports, raising aggregate demand and calling forth a higher level of Home output, Y. A two-country model of macroeconomic interdependence under a floating rate The FF schedule shows the Home and Foreign output levels at which aggregate demand equals aggregate supply in Foreign. FF also slopes upward because a rise in Y raises demand for Foreign exports, and Foreign output, Y*, must rise to meet this increase in aggregate demand. At the intersection of HH and FF, aggregate demand and supply are equal in both countries, given the real exchange rate. HH is steeper than FF. The slopes of the two schedules differ in this way because a rise in a country’s output has a greater effect on its own output market than on the foreign one. Changes in fiscal policy at home or abroad shift the schedules by altering government purchases, G and G*, and net taxes, T and T*. In addition, both fiscal policies and monetary policies can affect HH and FF by influencing the exchange rate. Macroeconomic Interdependence Under a Floating Rate Assume that there are two large countries, Home and Foreign. Macroeconomic interdependence between Home and Foreign: Effect of a permanent monetary expansion by Home Home output rises, Home’s currency depreciates, and Foreign output may rise or fall. Effect of a permanent fiscal expansion by Home Home output rises, Home’s currency appreciates, and Foreign output rises. Unemployment Rates in Major Industrialized Countries, 1978-2000 (percent of civilian labor force) Inflation Rates in Major Industrialized Countries 1981-2000, and 19611971 Average (percent per year) Exchange Rate Changes Since the Louvre Accord What Has Been Learned Since 1973? Monetary Policy Autonomy Floating exchange rates allowed a much larger international divergence in inflation rates. High-inflation countries have tended to have weaker currencies than their low-inflation neighbors. In the short run, the effects of monetary and fiscal changes are transmitted across national borders under floating rates. There is no question that floating gave central banks the ability to control their money supplies and to choose their preferred rates of trend inflation. Over the floating-rate period as a whole, higher inflation has been associated with greater currency depreciation. The exact relationship predicted by relative PPP, however, has not held for most countries. Exchange Rate Trends and Inflation Differentials,1973-2000 Monetary Policy Autonomy After 1973 central banks intervened repeatedly in the foreign exchange market to alter currency values. Why did central banks continue to intervene even in the absence of any formal obligation to do so? To stabilize output and the price level when certain disturbances occur To prevent sharp changes in the international competitiveness of tradable goods sectors Monetary changes had a much greater short-run effect on the real exchange rate under a floating nominal exchange rate than under a fixed one. Over the floating-rate period as a whole, higher inflation has been associated with greater currency depreciation. The exact relationship predicted by relative PPP, however, has not held for most countries. Monetary Policy Autonomy While the inflation insulation part of the policy autonomy argument is broadly supported as a long-run proposition, economic analysis and experience both show that in the short run, the effects of monetary as well as fiscal changes are transmitted across national borders under floating rates. The critics of floating were right in claiming that floating rates would not insulate countries completely from foreign policy shocks. Experience has also given dramatic support to the skeptics who argued that no central bank can be indifferent to its currency’s value in the foreign exchange market. Monetary Policy Autonomy Advocates of floating had argued that central banks would not need to hold foreign reserves. Even in the presence of output market disturbances, central banks wanted to slow exchange rate movements to prevent sharp changes in the international competitiveness of their tradable goods sectors. Those skeptical of the autonomy argument had also predicted that while floating would allow central banks to control nominal money supplies, their ability to affect output would still be limited by the price level’s tendency to respond more quickly to monetary changes under a floating rate. Symmetry The international monetary system did not become symmetric until after 1973. Central banks continued to hold dollar reserves and intervene. The current floating-rate system is similar in some ways to the asymmetric reserve currency system underlying the Bretton Woods arrangements (McKinnon). Because central banks continued to hold dollar reserves and intervene, the international monetary system did not become symmetric after 1973. Ronald McKinnon has argued that the current floating-rate system is similar in some ways to the asymmetric reserve currency system underlying the Bretton Woods arrangements. He suggests that changes in the world money supply would have been dampened under a more symmetric monetary adjustment mechanism. The Exchange Rate as an Automatic Stabilizer Experience with the two oil shocks favors floating exchange rates. The effects of the U.S. fiscal expansion after 1981 provide mixed evidence on the success of floating exchange rates. Under floating, many countries were able to relax the capital controls put in place earlier. The progressive loosening of controls spurred the rapid growth of a global financial industry and allowed countries to realize greater gains from intertemporal trade. The effects of the U.S. fiscal expansion after 1981 illustrate the stabilizing properties of a floating exchange rate. The dollar’s appreciation after 1981 also illustrates a problem with the view that floating rates can cushion the economy from real disturbances such as shifts in aggregate demand. The Exchange Rate as an Automatic Stabilizer Permanent changes in goods market conditions require eventual adjustment in real exchange rates that can be speeded by a floating-rate system. Foreign exchange intervention to peg nominal exchange rates cannot prevent this eventual adjustment because money is neutral in the long run and thus is powerless to alter relative prices permanently. Some adverse developments followed the adoption of floating dollar exchange rates, but this coincidence does not prove that floating rates were their cause. Discipline Inflation rates accelerated after 1973 and remained high through the second oil shock. The system placed fewer obvious restraints on unbalanced fiscal policies. Example: The high U.S. government budget deficits of the 1980s. The concerted disinflation in industrial countries after 1979 proved that central banks could resist the temptations of inflation under floating rates . The system placed fewer obvious restraints on unbalanced fiscal policies. Destabilizing Speculation Floating exchange rates have exhibited much more day-to-day volatility. The question of whether exchange rate volatility has been excessive is controversial. In the longer term, exchange rates have roughly reflected fundamental changes in monetary and fiscal policies and not destabilizing speculation. Experience with floating exchange rates contradicts the idea that arbitrary exchange rate movements can lead to “vicious circles” of inflation and depreciation. Exchange rates are asset prices, and so considerable volatility is to be expected. The asset price nature of exchange rates was not well understood by economists before the 1970s. Destabilizing Speculation Even with the benefit of hindsight, however, short-term exchange rate movements can be quite difficult to relate to actual news about economic events that affect currency values. Over the long term, however, exchange rates have roughly reflected fundamental changes in monetary and fiscal policies, and their broad movements do not appear to be the result of destabilizing speculation. The experience with floating rates has not supported the idea that arbitrary exchange rate movements can lead to “vicious circles” of inflation and depreciation. International Trade and Investment International financial intermediation expanded strongly after 1973 as countries lowered barriers to capital movement. For most countries, the extent of their international trade shows a rising trend after the move to floating. Critics of floating had predicted that international trade and investment would suffer as a result of increased uncertainty. The prediction was certainly wrong with regard to investment. There is controversy about the effects of floating rates on international trade. International Trade and Investment A very crude but direct measure of the extent of a country’s international trade is the average of its imports and exports of goods and services, divided by its output. Evaluation of the effects of floating rates on world trade is complicated further by the activities of multinational firms, many of which expanded their international production operations in the years after 1973. International trade has recently been threatened by the resurgence of protectionism, a symptom of slower economic growth and wide swings in real exchange rates, which have been labeled misalignments. Policy Coordination Floating exchange rates have not promoted international policy coordination. Critics of floating have not made a strong case that the problem of beggar-thy-neighbor policies would disappear under an alternative currency regime. Government are often motivated by their own interest rather than that of the community. It seems doubtful that an exchange rate system alone can restrain a government from following its own perceived interest when it formulates macroeconomic policies. Are Fixed Exchange Rates Even an Option for Most Countries? Maintaining fixed exchange rates in the long-run requires strict controls over capital movements. Attempts to fix exchange rates will necessarily lack credibility and be relatively short-lived. Fixed rates will not deliver the benefits promised by their proponents. The post - Bretton Woods experience suggests another hypothesis: durable fixed exchange rate arrangements may not even be possible. This pessimistic view of fixed exchange rates is based on the theory that speculative currency crises can, at least in part, be self-fulfilling events. At the end of the twentieth century, speculative attacks on fixed exchange rate arrangements were occurring with seemingly increasing frequency. Directions for Reform The experience with floating exchange rates since 1973 shows that neither side in the debate over floating was entirely right in its predictions. No exchange rate system works well when countries “go it alone” and follow narrowly perceived self-interest. Severe limits on exchange rate flexibility are unlikely to be reinstated in the near future. Increased consultation among policymakers in the industrial countries should improve the performance of floating rates. Globally balanced and stable policies are a prerequisite for the successful performance of any international monetary system. Directions for Reform Current proposals to reform the international monetary system run the gamut from a more elaborate system of target zones for the dollar to the resurrection of fixed rates to the introduction of a single world currency. Because countries seem unwilling to give up the autonomy floating dollar rates have given them, it is unlikely that any of these changes is in the cards. With greater policy cooperation among the main players, there is no reason why floating exchange rates should not function tolerable well in the future. Cooperation should be sought as an end in itself and not as the indirect result of exchange rate rules. Question Thanks