UNIT 4 NOTES

advertisement

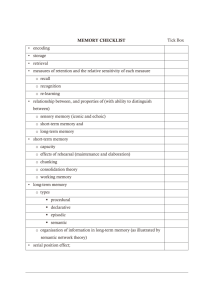

Unit 4 Summary MEMORY Memory involves an active information-processing system that receives, organises, stores and recovers information (p250) Three key processes are involved if information is to be remembered: ENCODING changes information into a form that can be stored in memory STORAGE involves holding and preserving information in a memory system RETRIEVAL involves recovering the information from memory so it can be used Memory is measured in three main ways Recall which involves supplying or reproducing facts or information with minimal external cues. Recognition memory where material previously seen or learned is identified from alternatives as being familiar. Relearning involves learning something that was previously learned - it is the most sensitive measure of memory. Also called the method of savings. (p276) LEVELS OF MEMORY There are three different but related levels of memory: sensory memory, short-term memory and long-term memory. SENSORY MEMORY A form of memory that “holds onto” an exact but brief copy of input from the environment to allow an analysis of the input to see if it is useful or needed etc. From here it might be transferred to short-term memory. Sensory memory for vision = iconic Sensory memory for hearing = echoic We have separate sensory registers for all our sensory receptors (senses). SHORT TERM MEMORY It involves small, short term storage for material that is actively being thought about or worked on. Size or capacity for most people is 7 2 pieces of information, but “chunking” can increase capacity. Unless rehearsed, material stays in STM for about 18 seconds max. STM also called working or active memory. Short-term memory is prolonged by use of maintenance rehearsal. LONG TERM MEMORY Involves unlimited and relatively permanent storage. Important and meaningful information is stored in LTM. LTM is what we usually refer to when we talk about memory. 2 Forms of Rehearsal : Maintenance rehearsal maintains information in STM by use of repetition. There is no attempt made to make sense of the information. Elaborative rehearsal makes information memorable and meaningful by relating it to other knowledge already stored in LTM. Consolidation Theory Consolidation involves the formation of a long term memory. Structural changes in the brain, associated with memory, must remain undisturbed for some time to establish the memory. Note the importance in the Hippocampus in the process STMLTM. Types of Long Term Memory Semantic I know……. Is like a mental dictionary or basic encyclopaedia of ‘facts’ about the world. Eg., names of days, months and laws etc. Is stable over time Is resistant to forgetting DECLARATIVE EPISODIC SEMANTIC and Episodic I remember……. Contains memories of past experiences. Eg., our first day at school, name of our first love, what we had for breakfast yesterday. Is less stable because information is pushed out by endless streams of new and relevant incoming information. Less resistant to forgetting PROCEDURAL LTM DECLARATIVE MEMORY (also called Propositional or Fact memory) is a form of LTM used for storing knowledge and facts. It involves the ability to learn names, faces, words, dates and ideas. There are two types of declarative memory: episodic and semantic. PROCEDURAL MEMORY: The part of LTM that contains knowledge of how to perform certain skills eg. riding a bike, tying shoe laces, typing. It is resistant to forgetting. Semantic Network Theory Relates to the way LTM is thought to be organised. Various concepts stored in memory can be thought of as connected meaningfully by links. Concepts closely related have short links and are “activated” if a particular memory occurs, whereas concepts which are not closely related have much longer links, and are further apart in memory making them take longer to retrieve. This theory also suggests that one memory may act as a retrieval cue for other memories related to it. Bower (1969) showed that information that is encoded in an organised way, assists later retrieval when compared to unorganised information. 3 Serial Position Effect From a list of words, early words and later words, are the best remembered. Early words (the primacy effect) are rehearsed, receive more attention, and therefore move to LTM. Later words (the recency effect) are remembered because they are still in STM. FORGETTING People are susceptible to forgetting. Various strategies have been devised to minimise forgetting and to improve encoding and retrieval of information from LTM. In STM, forgetting occurs mostly due to displacement or decay, but generically “forgetting” refers to loss of material from LTM. The Forgetting Curve Know the Ebbinghaus experiments here! Remember that his experiments (on himself) involved many,many variations. For example, both relearning and the forgetting curve are separate experiments. The forgetting curve shows recall is less if we wait longer to recall it. It shows more material is forgotten early in the retention interval,..and that the rate of forgetting slows as time passeswith more than half of the memory loss happening within the first hour after learning. Remember that the forgetting curve shows the rate and amount of forgetting through time (p281). Organic Causes of Forgetting The amnesias Anterograde amnesia involves forgetting of events AFTER injury or trauma. Retrograde amnesia involves forgetting of events BEFORE injury or trauma. Amnesia may involve both types, in reality. Alzheimer’s disease is a physical disease involving degeneration of brain cells causing a severe decline in mental abilities, personal skills, personality and behaviour. It involves severe degeneration of neurons in the hippocampus and mid-brain. A possible or probable diagnosis only. Causes are unknown though a genetic link has been established. Some researchers believe it is the result of a slow virus which invades the nervous system, or the result of an amalgam of destructive environmental toxins on brain tissue. While Alzheimer's is related to age, age does not cause the disease . (p286) Studies of memory decline over the lifespan show whether or not memory loss occurs in older people depends on the way memory is measured. Older people in some studies were less able to recall information, but their ability to recognise information remained unchanged. Other studies showed procedural memory and semantic (LTM) remained intact, but the ability of episodic memory declined. A complex and challenging life seems to help older people retain many mental abilities including memory- suggesting we should use it or lose it! (p288) 4 Theories on Forgetting Retrieval Failure theory (or cue-dependent forgetting) A basic assumption of “cue-dependency theory”, is that the presence of cues enhances memory, but if absent at the time of retrieval, forgetting may result. This may lead to the “tipof-the-tongue phenomenon”. It is likely that memories are stored as pieces or fragments, so that we might recall what a word starts with, what it sounds like, or how many syllables it has. Interference Theory Suggests that what matters in forgetting is what happens between learning and recall. 1 Proactive interference occurs when old learning interferes with new learning – so past learning causes interference. 2 Retroactive interference occurs when new learning interferes with ability to recall old learning -So new memories cause interference. Decay Theory Is the oldest theory of why we forget, and states that memory traces fade over time if they are not used sometimes. The limitation of this theory is that some people have vivid memories which have not been activated for years and years. Motivated Forgetting (Repression) Painful, threatening or embarrassing memories are held out of consciousness by forces within one’s personality. Eg. traumatic childhood experiences. This is different from suppression, where people deliberately try to forget something unpleasant. (Note that repression is currently a contentious issue). It’s likely that forgetting involves motivation/emotional phenomena. decay, interference, cue-dependency and The tip of the tongue phenomenon refers to the experience of having a memory we know we have, but it stays just out of reach. This phenomenon is significant because it shows that retrieval is not an all or nothing event. It shows information we want might still be stored in our memory, but not accessible unless the right retrieval cues are used (p300). ENHANCING RETRIEVAL Organisation encoding information in an organised way helps with retrieval. Context recall is enhanced if the cues present at the time of learning are also present at the time of retrieval. This is known as encoding specificity. For example, recreating context can help recall....where do I know you from? State-dependent cues there is evidence that information learnt in a particular bodily state may be better recalled in that state than in another e.g. information learnt when drugged, may be recalled better when drugged. eg. information learnt by divers underwater is best recalled underwater. Whilst much of this research is questionable, it does show the importance of context ie. learning occurs “in context”. 5 MNEMONIC DEVICES A mnemonic is a memory aid. Some mnemonics include using: The Method of loci which involves a series of locations and use of visual imagery. The peg-word system which uses visual imagery to visualise items to be remembered on mental markers. Narrative chaining which involves chaining together unrelated items so they are related in a meaningful story which recalls items as the story is told. Acrostics involve making verbal associations through making phrases from the first letters of the items which need to be remembered. Acronyms are types of words which are made from first letters of a sequence of words. Eg., ANZAC WHO Rhymes Eg.,thirty days hath September, April, June and…. The success of these techniques really depends on the type of material to be recalled. LEARNING To begin with it is important to understand what does involve learning, and what doesn’t involve learning. LEARNING refers to any relatively permanent change in behaviour that can be attributed to experience (and also to a change in the potential of our behaviour). Some changes in our behaviour during our lives are not due to learning but due to: Reflexes which are simple involuntary and automatic behaviours which occur in the absence of experience. Eg., when a young infant is touched on the cheek it automatically turns its head toward the stimulus touching it. Fixed Action Patterns are complex automatic sequences of behaviour which are performed identically by members of the same species. They may be sex-specific as well. Eg.,salmon travel many thousands of kilometres to breed in the distant rivers they were born in. Maturation-dependent behaviours are genetically programmed changes (in behaviour) which occur due to changes in the nervous system and body in the developmental process as we mature. Practice and experience do not have a noticeable influence on these genetically programmed changes. Eg., the change from crawling to standing to walking in an infant. A boy’s voice which deepens at puberty. Other brief behavioural changes occurring due to fatigue, illness, injury, drugs and alcohol are not considered due to learning – as they are brief. 6 The nature of learning: It may occur deliberately or unintentionally It may be immediate or delayed It may be possible, but not evident or demonstrated It is relatively permanent It is ongoing, and occurs throughout our lives Learning is measured by performance under experimental conditions. It usually produces a learning curve. eg. No. correct respons es No. errors trials trials CLASSICAL CONDITIONING Classical conditioning involves acquiring an association between a stimulus and a response which did not exist previously. (It was identified by I. Pavlov, and is also referred to as respondent conditioning). Before conditioning CS no salivation (bell) US UR (salivation) (food) During conditioning CS (bell) + UR US (salivation) (food) After Conditioning CS UR (bell) (salivation) so we know conditioning has occurred when the bell alone produces the CR of salivation 7 Terms in Classical Conditioning Neutral Stimulus a stimulus that doesn’t evoke a response. Conditioned Stimulus a stimulus to which a learned response occurs. Unconditioned Stimulus it reliably produces an automatic response, or an involuntary emotional response. Unconditioned Response an automatic, built-in and unlearned response. Conditioned Response a learned response to a stimulus. Acquisition refers to the training stage, which ends when the CS alone produces the CR. Extinction refers to weakening of the CR by removal of the US (linked to the CS). Spontaneous Recovery occurs when the CS produces the CR after extinction. Generalisation a response to a stimulus, different from, but similar to the original CS. Discrimination involves learning not to generalise and respond to similar stimuli to the CS. Higher-order conditioning takes place when a well-learned CS acts as a US and reinforces further learning. This way earning can be extended one or more steps beyond the original CS. Vicarious classical conditioning is classical conditioning occurring through observation of others being classically conditioned. Classical conditioning in everyday life involves: simple behaviours are simple conditioned reflexes. Eg.,students pack up their books when the bell goes, and entire audiences in a movie theatre are hushed as the light dims. complex behaviours include conditioned emotional responses ( which occur when the ANS produces a response to a stimulus it didn’t previously). For example, Watson’s experiment with Little Albert B. (p333) Make sure you are familiar with this experiment in relation to breaches of the contemporary code of ethics by The Australian Psychological Society (p35). Phobias are also complex behaviours thought to be learned through classical conditioning. Phobias are sometimes treated with systematic desensitisation which is a behaviour therapy based on the principles of CC (p338). Taste aversion which is thought to occur through a form of classical conditioning. Make sure you are aware that taste aversion develops in one trial (one-trial learning), but that one-trial learning differs from 'ordinary' classical conditioning in several ways (p340). 1 It occurs after one pairing so is quick to establish (while CC requires a number of pairings). 2 It is resistant to extinction (whereas CC is extinguished relatively quickly). 3 In one-trial learning the UR (being ill) is delayed and occurs well after presentation of the US (poisoned food etc.),whereas in CC the US is presented immediately after the CS, with the association made because both stimuli (the US and CS) follow closely in time. 4 We don’t usually generalise to other similar stimuli after one-trial learning (eg., other foods do not substitute for the particular food which is the CS) 8 Aversion therapy can be used to stop some undesirable behaviours such as smoking, fetishes, transvestism and others by learning to associate a strong aversion with the undesired habit. eg., Clockwork Orange OPERANT CONDITIONING It actually began with the work of Thorndike who proposed the law of effect after his work with cats in puzzle boxes. The law of effect stated that behaviours with satisfying consequences tend to repeated, and those with annoying consequences tend to be weakened. Thorndike called the type of learning he observed trial and error learning. He also called it instrumental conditioning because his cats were instrumental (took an active role) in escaping the puzzle box to get food. Later B.F. Skinner developed the Skinner box and used it to further develop and study Thorndike’s ideas on learning. However, he referred to the form of learning he studied as operant conditioning, and he emphasised that both people and animals learn to operate on the environment to produce satisfying or desired consequences. Skinner compared operants with respondents An operant is an active response which operates on the environment to produce some type of effect. It occurs in the absence of a particular stimulus. Eg., Thorndike’s cats made many varied operant responses as they tried to escape the cage because the responses they made were not elicited by a particular stimulus. A respondent is a response elicited by a particular stimulus. Eg., Pavlov’s dogs salivated to the meat powder and then later to the bell. Terms in Operant Conditioning A Reinforcer is any stimulus which brings about learning and increases the probability that a particular response will occur. A Positive reinforcer strengthens a response by following behaviour with something pleasant or liked by the learner. A Negative reinforcer strengthens a response and involves the reduction or removal of an unpleasant stimulus following the behaviour. Note: Both positive and negative reinforcement increase the frequency or likelihood of a response because both end with a satisfying consequence. A Primary reinforcer is an unlearned reinforcer, usually satisfying physiological needs. Eg., food. A secondary reinforcer is one which often gains its reinforcing properties by association with a primary reinforcer. Eg., money because it buys food,drinks etc. (p353). Acquisition phase is where the response becomes stronger on each trial if followed by reinforcement. Shaping occurs when successive approximations to a behaviour are reinforced to bring about the desired behaviour over time. Extinction occurs if reinforcement is removed (spontaneous recovery may also occur as in classical conditioning). Stimulus Generalisation occurs when the response occurs to stimuli which are similar to the one which was reinforced. 9 Discrimination involves responding only to the stimulus which has been reinforced, and not to other stimuli which are similar to it. Punishment involves the application of an aversive stimulus to change or stop a behaviour. Note the difference between punishment and negative reinforcement! Side effects of Punishment…. Person receiving punishment can come to dislike/fear or mistrust the punisher; punishment can lead to aggression; punishment may negatively reinforce the person doing the punishing, increasing both the frequency and severity use of punishment in the future; instead of changing behaviour, the person being punished may become better at avoiding detection; and in some cases it may actually work as a positive reinforcer (p365). Effective use of Punishment involves consistency; use of effective timing which should be quick and not lengthy (less delay the better); use of an effective punisher; and use of penalties instead of physical or psychological “pain” (p366). Response Cost is a term used to describe punishment that occurs as the result of removing a positive reinforcer. Eg., removing privileges like watching television as a punishment. THE SCHEDULES OF REINFORCEMENT - Partial reinforcement In Classical Conditioning, the US must be presented with the CS on every trial, or the strength of the CR will be weakened and extinction will commence. BUT in Operant Conditioning the strongest forms of conditioning are those with partial or intermittent reinforcement. Types of partial reinforcement schedules: Fixed ratio reinforcement follows after a certain number of responses Eg., FR-10 means every 10th time Variable ratio reinforcement follows after random number of responses (an average number is usually set) Eg. VR-10 means, on average, every 10th time. Behaviour reinforced on this schedule is very resistant to extinction. Fixed interval reinforcement follows after a fixed time interval. Eg., every 10 seconds. Variable interval no fixed time (but an average time is set). This type of reinforcement produces learning which is very resistant to extinction. In real life, more than one schedule may operate simultaneously. Eg., salaries/bonuses. Skinner found that learning under partial reinforcement is more resistant to extinction (than under continuous reinforcement). Variable ratio reinforcement is particularly resistant Eg., ‘pokies’ machines. Partial reinforcement also affects the speed and pattern of the response learned. 10 Applications of Operant Conditioning Behaviour modification involves the systematic use of the principles of learning to change or eliminate maladaptive or undesirable behaviour (p370). Animal training which is used in circuses and zoos, or to serve humans. Eg., guide dogs for the blind and disabled (p368). Token economies are basically point systems used to encourage order and discipline in institutions such as prisons, mental institutions and some schools. It can take the form of a therapeutic program where desirable behaviours are reinforced with tokens that can be exchanged later for goods, services or other privileges (p371). Conditioned Autonomic responses Eg., biofeedback techniques and therapy. Operant conditioning can be used to give the patient a certain amount of control over bodily functions such as blood pressure and heart rate. COMPARING CLASSICAL AND OPERANT CONDITIONING Similarities Both involve acquisition extinction generalisation discrimination Differences Classical Conditioning Operant Conditioning US occurs independently of organism’s behaviour (to produce UR). Reinforcement (US) occurs before the response. organism must DO something in order to get reinforcement. Reinforcement comes after response Partial reinforcement does NOT strengthen conditioning Partial reinforcement strengthens conditioning Usually conditions autonomic reactions (involuntary) eg. salivation, eye blink Usually conditions skeletal, motor reactions (voluntary) eg. bar press, running maze OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING Many patterns of behaviour are learned by observing and imitating the behaviour of others. (You should be aware of Bandura’s experiments with the Bo-Bo Doll here). Four sub-processes are involved in modelling 1. The learner must pay attention to the model. 2. The learner must remember what was done. 11 3. The learner must be able to reproduce (actually perform) the modelled behaviour. 4. The learner needs to be motivated to actually perform the behaviour. (There are 3 main types of reinforcement: external reinforcement, vicarious reinforcement and selfreinforcement.) Bandura also makes the distinction between the acquisition of a learned response and the performance of a response. His research shows that observing the consequences of a behaviour made a difference to whether or not the children modelled the aggressive behaviour they saw. If the learner and model share similarities like age and gender then the behaviour is more likely to be copied. The higher the status of the model the more likely it is they will be copied. (p378) Harrison’s cross-cultural training research which involves the four key elements of Bandura’s observational learning to prepare to work effectively in a different culture (p387). Other Forms of Learning include: Cognitive Learning is higher level learning, involving thinking, knowing, understanding and anticipation. It moves beyond basic conditioning into memory, thought, language and problem-solving. Latent Learning is “hidden” learning that doesn’t become obvious until a reward (or reinforcement) is offered. Learning by insight occurs when learning takes place by “insight” or sudden understanding, rather than by rote. (It may involve an “aha!” experience). The learning appears to happen suddenly after a flash of insight, and is usually complete and correct. Often the solution can be applied in similar situations (p390). Insight learning also occurs in four stages 1 Preparation the learner gathers relevant information 2 Incubation the learner appears to put the information on hold, but it is still processed an an unconscious level 3 Insightful experience the learner suddenly sees a solution, the ah-ha experience. 4 Verification the learner confirms the insight by testing it. (p388) Learning Sets help learners to solve new problems which are similar to past problems (or an original problem). A learning set refers to an improvement in the ability to learn resulting from the experience the learner has gained from a similar learning situation (p394). Learning sets involve a positive transfer of one’s learning. Eg., aircraft simulators provide trainee pilots with a learning set they can use later in real planes. 12 RESEARCH METHODS Researchers employ many different techniques or research methods to collect information (or data) on the behaviours they study in psychology. In unit 4 of psychology two research methods are studied: experiments and correlational studies. Use of statistics in psychology Statistics are used to enable researchers to make sense of the data they collect. They fall into two main categories: Descriptive statistics are used to describe, organise and provide a summary of aspects of the data so they can be made clear to others interested in the research. Calculation of mean scores on a test, or plotting results on a graph involves use of descriptive statistics. (p8) Inferential statistics allow the researcher to draw conclusions and make inferences from the collected data to determine whether the results of a study would occur and could be generalised to the wider population from which the smaller sample was taken originally. They allow the researcher to establish the statistical significance of the results and to decide if they have occurred due to chance or because of the predicted effect of the IV. The results of an experiment are tested by comparing the results of the groups involved in the experiment. If a statistical test shows that the results are due to the manipulation of the independent variable, and unlikely to be due to chance, they are said to be “statistically significant”. Statistical significance may be described with the statement p<0.05 which means that the probability (p) of the results obtained occurring by chance is less than 5 times in 100. In other words, the independent variable is most likely the cause of the observed experimental result. The Experiment In an experiment, the experimenter, manipulates a variable to see whether the manipulation affects another variable. An experiment is an attempt to determine what, if any, relationship exists between an independent and dependent variable. It aims to establish cause and effect. Variables are quantities which can increase or decrease in an experimental situation. The variable which is manipulated by the experimenter, and is plotted on the horizontal axis is called the independent variable. It is the suspected cause of a change in another variable. The variable which is measured by the experimenter, and is plotted on the vertical axis of a graph is known as the dependent variable. It shows the effect of the independent variable. Extraneous variables are any uncontrolled and unwanted variables apart from the independent variable which can cause the dependent variable to change. Confounding variables are uncontrolled variables present in the design of an experiment. Confounding variables vary with the IV and have a systematic effect on the dependent variable. A confounding variable works like another IV although it is not intended it should. Researchers need to provide operational definitions of a variable/s so the exact way it is tested and measured is made absolutely clear. 13 An hypothesis is a testable statement which makes a prediction about the nature of a relationship between two (or more) variables. An operationalised hypothesis is a very specific hypothesis stating how the variables studied will be manipulated and measured. This makes it very clear and testable. A control group is the group of participants who complete the experiment under “normal” conditions. It is selected to be as identical to the experimental group as possible, in every way except for the variable being tested. It is important in an experiment in order to determine whether it is the independent variable which has caused a change in the dependent variable, rather than another extraneous variable/s. The experimental group is the group of participants, under identical conditions to the control group, except for their exposure to the independent variable. Sometimes the same group of participants can be used under two different conditions, in which case a control group is not needed. A single-blind experiment is one where the subjects do not know whether they are in the experimental or control groups. A double-blind experiment is one where neither the subjects nor the experimenter knows which group the subjects are in. This prevents the researcher from influencing the subjects’ reaction. The experimenter effect can occur when the experimenter is able to influence the outcome of an experiment by his/her behaviour as perceived as expectations by the subjects. The experimenter unknowingly hints (through words, behaviour or actions) to subjects what is expected of them. A placebo is given to a subject to mimic the conditions in the experimental group, e.g. a pill that is a “blank”. It is given to control the effects of suggestion and expectation. The placebo effect occurs when the subject receiving the placebo are actually affected due to their psychological expectations of the outcomes of the experiment. The order effect can occur when the same experimental technique is used repeatedly and the performance of participants improves due to experience or deteriorates due to boredom, and not because of the effect of the independent variable. The conclusion of an experiment must always be based on the results of the experiment and invariably reflect on the hypothesis established before the experiment was conducted. Any generalisations are dangerous, including interpolation (interpretations within the range of data) and particularly extrapolation (interpretations beyond the bounds of the data). Some experimenters invite further experimentation, and this is fine, but to generalise from an experimental sample taken from a specific population of research interest to a wider population not represented in the sample, is scientifically unacceptable. 14 THE EXPERIMENT page 20 of text Various experimental Designs INDEPENDENT GROUPS DESIGN Each participant allocated to one separate groups Advantages of Design no order effects to control is randomly of 2 entirely MATCHED PARTICIPANTS DESIGN Involves selecting pairs of participants who are very similar in terms of characteristics which could affect the DV (IQ, creativity, age, gender) 2 and then randomly allocating each member of the pair to different groups REPEATED MEASURES DESIGN Is where each participant is involved in both the experimental and control condition in the experiment Limitations of Design less control over participant-related variables (like IQ and motivation) than other designs – especially if the sample is small controls participant-related variables because the experimental and control groups are matched on important participant-related variables likely to affect the DV controls participant-related extraneous variables because the same participants are used in the control and experimental condition, so the effects of individual differences are balanced out and identical in both groups possible presence of the order effect – where performance on a task completed second may benefit from the practice and experience gained in the first task impaired due to boredom the second time around can be controlled by counterbalancing which involves arranging the order in which the conditions of a repeated measures design are experienced, so that each condition occurs equally often in each position. For example, half the participants follow one order (solving the problem in the experimental condition first, then solving a problem in the control condition), and the other half follow the reverse order (solving a problem in the control condition first, and then solving a problem in the experimental condition). The experimenter must also ensure the order each participant is exposed to each condition is determined using a random allocation procedure - this means order effects are balanced out throughout experiment. 15 Populations and samples Sampling refers to the use of only a number of subjects from a population of research interest, rather than the entire population. It is important that the sample be representative of the population of research interest. Random sampling involves selecting subjects for an experiment in such a way that every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected to be a participant in a study. A simple way to get a random sample is use of a computer generated table of random numbers. Random allocation ensures participants have an equal chance of being in either the control or experimental group in an experiment. It helps to ensure that subject differences are evenly distributed across both groups so that any differences between the groups is due to the independent variable and not to participant-related differences. A biased sample occurs when some members of the population do not have an equal chance of being selected as a participant in a study. Stratified sampling refers to the random selection of participants from certain “strata” or groups that have been identified in the population. Mostly care is taken they occur in the same proportion in the sample as they do in the wider targetted population. For example, the experimenter might want 30% of his subjects to be under 18, and 20% to be retired, because that is representative of the population. Income, age and religion are all ways which could be used to divide a population into distinct strata (p9). Measures of relationship Correlation is a statistical measurement used to determine if two variables are related, and the strength and direction of the relationship. (p32) Correlation can be expressed in terms of what is known as a correlational coefficient where a decimal may be between -1 (strong negative correlation) and +1 (strong positive correlation). A correlation of 0 suggests no relationship between the two variables in question. A positive correlation means two variables vary in the same direction. As height increases appetite increases. (p32) A negative correlation means that two variables vary in the opposite direction. As one variable decreases the other increases. Hand steadiness increases as smoking decreases. (p32) A scattergram is a diagram used to plot correlational data. It shows a graph of the scores made by the same individuals for two different variables (or values). A straight line ruled through the middle of the spread of data is called the line of best fit. The line of best fit (or regression line) indicates if the correlation is a positive or negative one. (p32) 16 Ethical considerations in psychological research The Australian Psychological Society (APS) has published a code of ethics and guidelines for members who conduct psychological research. It identifies the responsibilities of the researcher and the participants' rights. Ethical issues relating to research (and other types of practice as well) fall into three main categories. Physical harm Psychological harm Rights as an individual confidentiality voluntary participation informed consent right to withdrawal deception in research debriefing