West, Laura (2014) Personality disorder & serious further offending

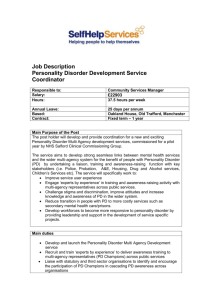

advertisement