Tax Planning Using Partnerships

advertisement

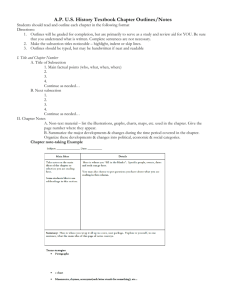

This paper was originally presented at the Canadian Tax Foundation 2003 Ontario Tax Conference on October 27, 2003 and is reprinted with permission. Tax Planning Using Partnerships By Robin J. MacKnight, B.A., LL.B., LL.M., TEP Wilson Vukelich LLP Based solely on the number of recent technical, administrative and judicial pronouncements concerning partnerships, one might think that they were becoming the latest trend in business planning. However, a closer analysis will show that many of these reflect a misunderstanding of how partnerships operate (either by those aspiring to use them, or by those attempting to tax them), a bias against the flow-through nature of the vehicle, or an excessive optimism over the profitability of start-up ventures. Although more taxpayers seem to be discovering the benefits of the partnership structure, it still seems to be misunderstood and under appreciated. This paper will discuss legislative proposals contained in the December 20, 2002 technical bill, some recent (2003) administrative pronouncements and court cases, and their impact on estate planning and tax shelter offerings. I. Recent Developments a. December 20, 2002 Technical Bill One of the anomalies in partnership taxation is the calculation of the adjusted cost base of a partnership interest. Income earned in one fiscal period of a partnership does not increase the adjusted cost base of the partnership interest until immediately after the end of the taxation year. However, any distributions from the partnership during the course of the fiscal year immediately reduce the adjusted cost base. Consequently, it is not unusual to find a partner in an operating partnership (particularly a healthy, profitable and expanding partnership) with a negative adjusted cost base in the middle of a fiscal period as a result of drawings which reduce the adjusted cost base of the partnership interest. This creates a particular problem for those who cease to be members of the partnership in the course of a fiscal period. Since partnership income is only allocated to those members of a partnership at the end of its fiscal period, it is not clear how any stub period earnings are to be allocated to members of a partnership who leave mid-year. Consider the situation where a partner retires on June 30 (half way through the partnership year). By that time, the partnership has realized only 30% of the anticipated profits for the year plus a capital gain. The balance of the anticipated 70% of the income was realized in the latter half of the year, along with a capital loss which offset the capital gain. What should be allocated to the retiring partner as at June 30? While the partnership agreement should address this issue, it cannot dictate the tax consequences. If the partner has received distributions during the stub period, the adjusted cost base of that partner's interest will be reduced and, if it becomes negative, a capital gain will arise on the disposition arising when the member ceases to be a partner. However, there would be no increase in that adjusted cost base to reflect the profits earned during that stub period since the income allocation occurs only after the year end of the partnership, at which time the member will not be a partner and will not be entitled to any allocation. New subsection 96(1.01) is designed to at least partly alleviate this problem. Under this new provision, where a taxpayer ceases to be a member of a partnership in mid year, its fiscal period is deemed to end immediately before the time the taxpayer ceased to be a member (subparagraph 96(1.01)(b)(ii)) and the taxpayer is deemed to be a member of the partnership at the end of the fiscal period (paragraph 96(1.01)(a)). Consequently, there can be an allocation of income, gain or loss which will be included in computing the partner's adjusted cost base and recognized in calculating any gain or loss on the disposition of the partnership interest. A complementary change is found in proposed subsection 100(5). This provision deems a taxpayer to have a capital loss from a disposition of property where an amount is paid after the taxpayer has disposed of a partnership interest, and the amount would have been considered a contribution to partnership capital had it been paid while the taxpayer was a partner. Consider the example above. The terms of the partnership agreement require the taxpayer to contribute capital to the partnership if it realizes a net loss from operations during its fiscal period. The taxpayer resigned from the partnership mid year, before the net loss was realized, and before the obligation to pay crystallized. Assume the taxpayer realized a capital gain on the disposition of the partnership interest (even after the mid year adjustments under subsection 96(1.01). If the taxpayer subsequently paid an amount which would otherwise have been considered a contribution to partnership capital, that amount is deemed to be a capital loss from a disposition of property and can be carried back to offset the gain realized on the original disposition. b. Administrative Pronouncements Income Splitting for Retired Partners - Document 2003-0006465 Subsection 96(1.1) allows partnership income to be allocated to a retired partner, that partner's spouse or common-law partner, or to that partner's estate or heirs (or certain other designated people). The income so allocated is included in the recipient's income under paragraph 96(1.1)(b). The CCRA was asked to consider whether a partnership agreement could be amended to allow a retired partner to share partnership income with that individual's spouse. Not surprisingly, the response was discouraging. The CCRA agreed that the income so shared with the spouse would be included in the spouse's income under paragraph 96(1.1)(b); however, that same amount would also be included in the partner's income under subsection 56(2) or (4). Further, subsection 248(28) would not apply to prevent this result. Director Fees of Partnership - Document 2003-0020315 The issue here was whether source deductions are required in respect of directors fees paid to a partnership which provides the services of the director as part of its normal business activities. The classic case is a partner of a law firm who acts as a director for one of the firm's clients, but who is required by the terms of the partnership agreement to remit those fees to the firm. These fees then become income of the partnership, rather than income of the partner. The technical interpretation confirms the comments in Interpretation Bulletin IT-377R. So long as the fees are not earned by the individual "in the course of, or by virtue of an office or employment", but are earned by the partnership (or corporation) in the course of carrying on its business, the fees do not represent "salary, wages or other remuneration" which would attract withholding obligations under section 153 and the corresponding regulations. Partnership Information Returns - Document 2003-0181425 Penalties are exigible for failure to file information returns in a timely manner. Specifically, a partnership is liable for each failure to file to a penalty of $25 per day for each day the return is late, with a minimum penalty of $100 and a maximum penalty of $2,500. The partners are also liable to this penalty if they distribute information slips late. The question was asked whether each partner could be subject to the penalty even though, in practice, the partnership distributes the T5013 information returns to the partners. The answer is yes. Subsection 229(1) of the regulations requires "every member of a partnership that carries on business in Canada … at any time in a fiscal period of the partnership" to make for that period an information return in prescribed form containing specific information. Further, section 209 of the regulations requires every person who is required by section 229 to make an information return, to forward that return to each person to whom the return relates. The net effect of these two sections is to impose the distribution obligation on the members of the partnership, not the partnership itself. Consequently, if the members of the partnership do not comply with section 209, each member of the partnership will be liable to a penalty under paragraph 167(7)(b) of the Act for failing to comply with a duty or obligation imposed by the regulations. If the partnership return is not filed within the time set out in subsection 229(5) of the regulations, the partnership (but not the partners) will be liable for a penalty by virtue of subsection 167(1.1) of the Act. Note that subsection 229(2) provides that an information return made by any member of a partnership is deemed to have been made by each member of the partnership. Many partnership agreements (including those used in tax shelter structures) require a "tax matters" partner (usually the managing partner or a general partner in a limited partnership) to file all necessary information returns on behalf of the partnership. But what happens if the tax shelter fails, and the general partner ceases to operate? Can the limited partners gather the necessary information? If they do, could they be seen to be managing the partnership, and thereby lose their limited liability? Just one more risk for investors! Capital Tax for Corporate Partners - Document 2003-0181695 The provisions of Part I.3 are not crystal clear when it comes to integrating partnership profits and corporate partner capital. The December 20, 2002 technical amendments do not address the issue raised in this technical interpretation, and the CCRA has apparently asked the Department of Finance to amend the legislation to clarify the policy intent of this provision. The question was asked how current period profits were to be reflected in calculating LCT. The LCT clearly includes allocated partnership earnings for a fiscal period of a partnership that ends in the corporate partner's taxation year (paragraph 181.2(3)(g) - so for instance the earnings of a partnership with a June 30, 2003 year end would be included in the current year income and LCT calculation of a calendar year corporate taxpayer). But what about partnership earnings during the current partnership fiscal stub period (i.e. the earnings from July 1 to December 31, 2003)? The technical interpretation confirms that a corporate partner's share of earnings from a partnership's fiscal period that ends in the corporate partner's taxation year are included in calculating taxable capital, whether or not such earnings have been distributed. Further, no portion of the earnings of a partnership for the stub period between the fiscal year end of the partnership and the fiscal year end of the corporate partner (the July to December period) would be included in calculating taxable capital unless the corporate partner has received a distribution of stub period earnings. Where stub period earnings have been distributed, and the amount of the distribution has been recorded in the corporate partner accounts in accordance with GAAP as a debit to cash and a credit to retained earnings, the amount of the distribution must be included in the capital of the corporate partner under paragraph 181.2(3)(a). This same result would occur if the distribution was characterized as an advance. There appears to be a risk of double counting partnership profits in LCT calculations. If an operating partnership routinely distributes earnings during the stub period, this technical interpretation would require those distributions to be included in the LCT calculation - so in the example, the stub period earnings July to December 2003 would be included in the corporate partner's 2003 (calendar) year end. However, the partnership year end allocations arising on June 30, 2004 would be included in the corporate partner's 2004 LCT calculation. There is no express provision that would back out that portion of the partnership's profits that had already been included in the corporate partner's 2003 LCT computation. As the technical interpretation notes, "the provisions in Part I.3 are somewhat ambiguous as they relate to the treatment of partnership earnings" - hopefully the Department of Finance will respond with some clarifying legislation. Partnerships as Conduits Two recent technical interpretations address the conduit nature of a partnership. Document number 2003-0027745 deals with the flow through of the inter-corporate dividend deduction, while document 2003-0020015 deals with foreign tax credits. The first question concerned a partnership of corporations resident in Canada. The partnership owned shares of a CCPC which paid dividends which were allocated to the corporate partners. The technical interpretation confirmed that the corporate partners could claim the deduction under subsection 112(1) for the dividends allocated from the partnership. This confirms the separate source of income concept set out in paragraph 96(1)(f). The second question dealt with an individual resident in Canada who was a member of a partnership that owned and operated a golf course in Wales. This technical interpretation also confirms that the characteristics of source and nature of income flows through the partnership to the partners. In this case, a share of the partnership business income earned in Wales would be attributed to the Canadian resident partner. Since the partnership earned business profits through a permanent establishment in the UK, its profits were also taxable in the UK. The technical interpretation confirmed that the individual partner resident in Canada may claim a foreign tax credit under subsection 126(2) for the business income tax paid in the UK. If that foreign business tax could not be fully credited under subsection 126(2) in a particular year, the excess could either be carried back three years or forward seven years, provided the taxpayer remained resident in Canada and had income from business carried on the UK in those years. Bonuses to Indirect Shareholders of Corporate Partners - Document 2003-0034035 At the 2001 Annual Conference, the CCRA confirmed that it would not challenge the reasonableness of bonuses paid to active shareholders of CCPC's which routinely "bonused down" to the small business limit. This document expands on the application of that administrative position. The situation involved an individual resident in Canada (the "shareholder") who owned all the shares of Holdco, a CCPC, which in turn owned all the shares of A Ltd. which was also a CCPC. A Ltd. acted as general partner of several Canadian partnerships and all its income was derived from its interest in those partnerships. The shareholder was actively involved in the management of A Ltd. and in the income earning activities of the various partnerships. A Ltd. proposed to pay salary and bonuses to the shareholder equal to the income it received from its partnership interests. The question was whether CCRA administrative policies noted above would apply. The Agency confirmed that managing a CCPC's interest in a Canadian partnership as a general partner, and being involved in the day-to-day operations of the partnership, would satisfy the requirement that the shareholder be actively involved in the operations of the CCPC. However, this position would not automatically extend to CCPC's who were limited partners. In such situations, it would be a question of fact whether the shareholder was actively involved in the day to day operations of the CCPC. Where all the income earned by the CCPC is partnership income attributable to the limited partnership interests, and the shareholder is actively involved in the operations of the CCPC, the administrative position could apply. While this interpretation is good news for general partners, it presents difficulties for limited partners. If a limited partner is actively involved in the partnership business, it could lose its limited liability. Consequently, individuals who are shareholders of limited partners must ensure that their involvement in the management of the limited partnership business comes as a result of their position as officers or employees of the general partner, and not in any way as a representative of the limited partner. It is not uncommon for investors in limited partnerships to wear two hats - one as officers and managers of the general partner which typically holds only a minority interest in the partnership (and consequently will not earn sufficient income to pay bonuses), and another as investor seeking liability protection through a limited partnership interest. Wearing their general partner hat, shareholders could be actively involved in the business, generating revenues and profits that accrued to them indirectly through their limited partnership interests. Hopefully bonus payments made to such active shareholders from their limited partner corporations will attract the same administrative treatment. Related Person - Document 2003-0004835 Unusual fact situations generate unusual responses. In this technical interpretation, a taxpayer who was a "majority interest partner" contributed assets to a partnership in exchange for a nominal incremental partnership interest. The economic interests of all other partners were clearly defined and were both comparatively nominal and unaffected by the contribution. The contributing partner did not intend to confer any benefit on the other partners, but was concerned that paragraph 85(1)(e.2) might apply if the partnership was considered a "person related to the taxpayer" because the contributor was a majority interest partner (note that paragraph 85(1)(e.2) specifically excludes transfers to wholly owned corporate subsidiaries). The technical interpretation states that paragraph 85(1)(e.2) would not apply in these circumstances - one can only speculate that the rationale was that if a wholly owned corporate subsidiary was excluded from its operation, an economically similar partnership should receive similar treatment. Debt Forgiveness - Documents 2003-0025815 and 2003-0020265 These technical interpretations confirm the application of section 80 where partnership debt owing to third party creditors and to partners is satisfied by the issuance of partnership interests. Document 2003-0025815 addresses the situation where a commercial debt obligation of the partnership is satisfied by issuing partnership units to the third party (i.e. non-partner) creditor. In general terms, the forgiven amount is the difference between the amount of the obligation and the amount paid to satisfy it. In this situation, the "amount paid" when the debt was retired in exchange for partnership units was the amount of cash the partnership would have received on the admission of a new partner, but which it gave up in return for the settlement of the debt obligation. This result is consistent with the corporate scenario, where shares are issued in settlement of a debt obligation (see paragraph 80(2)(g) - the fair market value of the share would presumably reflect the amount the corporation could otherwise receive on its issuance). Document 2003-0020265 deals with the situation where the partnership owes money to its partners, but satisfies the obligation by converting it to partnership capital. Generally, when a debt owing to a partner is converted to partnership capital, the adjusted cost base of the partnership interest is increased pursuant to subparagraph 53(1)(e)(iv) of the Act. If the converted amount is less than the principal amount of the debt, section 80 could apply. However, the nature of the partner's involvement in the business of the partnership is relevant in determining how section 80 applies. Section 80 has no effect where the partner is "actively engaged, on a regular, continuous and substantial basis" in the activities of the partnership. In such circumstances, the "forgiven amount" calculated under subsection 80(1) is nil. However, a limited partner will not meet these conditions in paragraph (k) of the definition of "forgiven amount", with the result that section 80 will apply to the partnership on the conversion of debt owing to a limited partner. Where section 80 applies, partners may include their share of the amount determined under subsection 80(13) in income (determined at the partnership level) or they may treat their share of the forgiven amount as if it was their own commercial debt obligation that is deemed to have been settled under subsection 80(15). Under this alternative, the particular partner's tax attributes will be reduced in accordance with the rules in section 80. This alternative recognizes that partners may have undeducted losses or other tax pools attributable to the activities of the partnership. The forgiveness of the obligation that is deemed to arise for the partner is treated in the same way as a forgiven amount in respect of an obligation issued by a debtor. c. Recent Cases of Significance There have been a number of cases in 2003 dealing directly with partnership taxation, or with issues that frequently arise in partnership taxation. Traditionally the courts have considered three conditions to determine the existence of a partnership: Two or more persons Carrying on a business in common With a view to profit. However, recent cases suggest that the second condition should be broken into two separate tests - is there a business, and if so, is it carried on "in common"? Notwithstanding the Supreme Court decisions in Continental Bank1 , that there is a low threshold for demonstrating the existence of a business, and in Stewart and Walls, that the REOP doctrine does not apply to commercial activities, a number of recent cases (which presumably commenced before the Stewart2 and Walls3 decisions came down) have considered whether a taxpayer was carrying on a business which generated losses. All of these cases are fact specific and none advances judicial thinking or provides enlightenment for tax planners. However, the fact that these cases reached the courts demonstrates that the CCRA has not rolled over on either REOP or the need to show commerciality in taxpayer activities before "business losses" can be deducted. Is there a business? In Gagnon4, the taxpayer set up a cabinet making operation to augment his employment income, anticipating an economic slow-down that would reduce his hours of work. He invested time and capital in setting up separate premises (not in his home) from which he operated. As things turned out, the taxpayer ended up working overtime with his employer, and had less time to devote to his independent operations. As the Tax Court concluded: "… the appellant invested a fairly substantial amount in the construction of a workshop, which he subsequently equipped with the tools needed to carry on his trade as a cabinetmaker. The workshop is a few kilometers from his residence and is used solely for the purposes of his trade. Although he does not devote all his time to his business, he operates it as a sideline to his regular work. The appellant's intentions at the outset were to use his business to supplement his income during periods of unemployment, but a permanent employment reduced his productivity. However, he continued devoting time to his business, accepting contracts and constantly operating it in accordance with his availability. He carried on his activities under a trade name and is registered for GST and QST purposes. He still hopes to operate his business on a full-time basis … I can conclude that he is carrying on his activities in a commercial manner and that there is a source of income in this case." At the other end of the spectrum, a taxpayer was still successful in demonstrating that his activities constituted "an adventure in the nature of trade" which constituted a business. In Quaidoo5, the taxpayer exported car parts, used cars and bicycles to Ghana, where he had family connections. The Minister asserted that there was a personal element to this venture, and disallowed the claim for deductions. While ultimately the taxpayer was unsuccessful because he had no business records to support his claim for deductions, the Tax Court did conclude there was some commerciality to the taxpayer's activities: "Turning to the first issue of whether Mr. Quaidoo was in business. I do not find that simply because a brother has lived in a possible market place and that parents have a property there, that this is the type of personal element that justifies finding Mr. Quaidoo was in a personal endeavour as opposed to the pursuit of profit. He simply stayed at a place owned by his parents while in Ghana, and relied upon some of his brother's contacts. There was no evidence that goods were sold or distributed to family or friends, or that the activity itself had a personal element. I find there was no personal element. What then was Mr. Quaidoo engaged in? Did he have a source of income? I do not accept the Respondent's suggestion that this trial run was a pre-business step. It was simply too involved a commercial activity to be considered such. The act alone of acquiring a container and shipping goods at a cost of $8,000 goes beyond mere pre-business inquiries. Yet Mr. Quaidoo showed none of the more formal trappings of a business. He had no business books, no business records, kept no logs, no addresses of contacts, no information from where he acquired the goods. He said he had a plan, but there was nothing in writing, no banking information. Indeed, virtually no documentation at all, apart from the three receipts, oddly disguised as invoices. At best, Mr. Quaidoo engaged in an adventure, an adventure in the nature of trade. This expression is perhaps well suited to what Mr. Quaidoo did. He ignored the formalities of actually carrying on a business and all that entailed, and simply rushed into an adventure, an adventure in the nature of trade. For tax purposes, however, that is a business." Other taxpayers have not been successful in convincing either the CCRA or the courts that their activities were commercial. In Dahl6, the taxpayer claimed expenses relating to a venture to sell ice cream to Cuba. The Tax Court was not impressed: "The Court also finds that the proposed expenses of the alleged activity in Cuba had a personal element of a vacation or similar personal activity in Cuba. In particular, the Appellant claimed expenses for his two children's trip to Cuba in 2000. That was not in any sense a business expense. It is fatal to any suggestion that there was no personal element. As a result, objectively the Court finds that no business was in place because: 1. There was no product as yet. 2. There was no contract or operation for the production of yoghurt cones. 3. There were no contracts after alleged promotions commencing in 1998. 4. There is still nothing and one proposed agency, Rumballs, was admittedly "on hold" for two years after 2000. With respect to the other expenses, the Appellant failed to prove any additional amounts that the Appeals Officer did not allow. In particular, he is an experienced commission salesman, yet he did not keep a vehicle log, he did not itemize and organize his alleged expenses by "vehicle", "entertainment", "gifts and promotion", et cetera. Rather, they were mixed up and filed in a manner that lacked credibility. He also failed to particularize his vehicle usage clearly between personal and business use." In a similar vein, the Tax Court in Johnson7 concluded that taxpayers engaged in horse racing activities were really just pursuing a hobby that did not have the appearance of ever generating a profit. Consequently their claim for deductions was denied. Is the Business carried on "in common"? One of the tests of partnership is the intention that all partners will actively participate in the business - that they will carry it on "in common". However, where no such intention exists, this condition must fail. A recent decision on a Quebec research and development scheme illustrates this point. In McKeown8, the taxpayers were encouraged to invest in a series of research and development schemes. Although Mr. McKeown did some due diligence to satisfy himself that the projects were realistic (he having some familiarity with the subject matter of the projects), his evidence was clear that he really only invested to get the tax benefits. As the Tax Court concluded: "The appellant said that Commu-Sys Enr. was established to form [TRANSLATION] "a group of people to amass funds to have research done". He admitted that he did not know the other investors in the group, aside from his co-workers who were members. He expressly admitted that, if there had been no tax benefits, [TRANSLATION] "we would not have created the partnership to invest; the partnership would not have existed". He would not have invested if there had been no tax refund. The appellant did not participate in any decisions concerning the partnership's business. Moreover, although they received millions of dollars from investors, the groups in question and their members, by and large, did not really care about the progress of the work or the results achieved. The members of the groups did not have any control, even in a general way, over the progress of the research work done by Omzar Technologies Inc. The members, including the appellant, did not participate in making any decisions relating to the groups' activities. They were not involved in the various stages of the research work. The investors merely followed Omzar Technologies Inc.'s instructions. The groups as such were totally inactive. On the evidence, I conclude that the investors in question were merely seeking substantial tax benefits and never demonstrated any intention of working together to undertake scientific research and experimental development activities. In short, they had no intention of forming a genuine partnership." While the partnership in McKeown was a general partnership, conceivably this argument could be made against many of the public tax shelter offerings. How reasonable is it to assume that limited partners scattered across the country have an intention to carry on a business with people they don't know and will probably never meet? Did they really invest for business purposes, or were they just looking for tax relief? I am not aware that this argument has been advanced as a basis for assessment in any of the outstanding tax shelter assessments or litigation. Reallocation of Income - Section 103 Section 103 has often been viewed as CCRA's "black box" to prevent income splitting through partnerships. The problem with applying this section is determining what is "reasonable" in the particular circumstances. It is difficult to set general rules for what must in any situation be peculiar to the particular facts. Two recent cases demonstrate the problem. In Spencer9, the appellants (husband and wife) operated an embroidery business. At the outset, each partner's share was 50%. This lasted four years. In year 5, the split changed to 85-15 in favour of the husband, and in year 6 it became 90-10. This split continued for years 7, 8 and 9, during which the partnership generated losses. During those years, the wife had no income, and the husband had substantial employment income, against which he sought to deduct the partnership losses. Interestingly, in year 10, the business was operated by the wife as a sole proprietorship, and it produced profits. During the years in question, the wife had child care responsibilities but was heavily involved with income tax and accounting matters for the partnership. She also took some sales orders and placed stock orders. She developed embroidery skills and ultimately continued the business. The husband supplied the financing, totaling some $200,000, although the wife was a guarantor of several loans. The Minister suggested a 50-50 split. The court found a middle ground, concluding that the wife had contributed considerably more than 10% to the operations of the business in the years in question. The court concluded that a 75-25 split in favour of the husband was appropriate in the circumstances. In Makaruk10, the issue was whether the appellant husband and wife were carrying on a car sales business in partnership. The Minister asserted that a partnership existed, and that the husband's share was 80%. The appellants maintained that the business was operated solely by the wife. The court concluded: "In applying these indicia of Continental Bank, together with section 4 of the Partnership Act to the facts presented before me, both Appellants shared one joint account, out of which they transacted business and personal activities. Both had a joint VISA account. There was a joint insurance policy on the vehicles. The Appellant, Adam Makaruk, had a thorough knowledge of the business activities and according to the evidence, far more than his wife. The business operated out of the residence that both Appellants shared. The Appellant, Adam Makaruk, had authority to purchase vehicles, to drop them off and pick them up when they were being serviced. He dropped off cheques to pay for various business related activities. He attended the auctions to bring back vehicles. He also handled sales of vehicles to third parties in the absence of his wife, thereby holding himself out to third parties as a partner. Given these circumstances and facts, I do not accept the Appellant's characterization respecting the nature of his involvement in the business activities. The facts support that he was carrying on this business in common with his wife. However, I do not agree with the Respondent's characterization that he was an 80 per cent owner of the business. The facts here support that the wife was involved in the business but to a far greater degree than the suggested 20 per cent. The circumstances here suggest that a more appropriate split would be a 50 per cent to each Appellant." Partnership Rollovers One of the most significant cases of the year considers the rollover of real estate inventory through a partnership to a loss company, and its ultimate sale by the loss company. The result might be surprising, but encouraging to tax planners. In Loyens11, the taxpayers were real estate developers. To satisfy a debt, the taxpayers had to transfer a piece of real estate to a company controlled by the person who had originally made the loan. After consulting their tax adviser, the taxpayers transferred the land first to an existing operating partnership, triggering a small amount of business income in their hands due to the partnership's assumption of some debt. The partners then transferred their respective partnership interests to their loss company, in separate transactions, which collapsed (or incorporated) the partnership. The loss company then transferred the property to the ultimate owner, reporting business income on the sale which was sheltered by loss carryforwards. All transactions occurred on the same day. The case is significant for two reasons. First, there is a detailed discussion of how to accomplish the incorporation of a partnership. Second, there is a detailed discussion of why GAAR does not apply. Incorporating the Partnership - Rollover of Partnership Interests The evidence disclosed that the two taxpayers, who were equal partners in an existing partnership ("Varna"), transferred the property into the partnership in exchange for an assumption of debt and a credit to their capital account. Each appellant also reported taxable business income as a result of the assumption of debt. Subsequently, on the same day, each taxpayer by a separate document transferred their partnership interest in Varna to the Lossco ("Lobro Stables"). The taxpayers filed an election pursuant to section 85 of the Act for the disposition of the partnership interest. These elections specified a fair market value for each individual partnership interest. The consideration received by each taxpayer was paid by the allotment and issuance of Class A special shares which were retractable and redeemable. Apparently the partnership interests had negative adjusted cost bases, so each taxpayer reported a capital gain as a result of this transfer into Lossco. Subsequent to these transactions and on the same day, Lossco sold the interest it now owned in the property to the purchaser. On this disposition, Lossco reported a gain on the sale, but offset that gain with accumulated loss carry forwards. Justice Campbell observed: "I do not believe that these transactions were artificial or manufactured. The legal relationships and their commercial reality are legitimate. The documents reflect the nature of these relationships." The Crown argued that the rollover of the partnership interest to Lossco was not valid under subsection 85(1) and 85(1.1) of the Act. The Crown's position was that the partnership dissolved because the transfer of both partner's interests to Lobro Stables as individuals violated partnership law. Lossco could not be the partner of the partnership because there must be at least two partners to comprise a partnership. What was transferred was the property and not the partnership interest. Justice Campbell disposed of this argument easily: "The respondent's argument has some merit but I believe it may apply only to a situation where the subsection 85(1) rollover of the partnership interest to the company is occurring at the same moment in time. Section 2 of the Ontario Partnership Act requires that a valid partnership have a minimum of two partners. The evidence in this Appeal supports the view that the transfer of the appellants' partnership interest did not occur simultaneously. The transfers of the appellants' respective interests in Varna to Lobro Stables are contained in two separate and distinct documents. This is noticeably different from the agreement in which each of the Appellant's interest in the Harrison property was rolled into the Varna partnership. This was accomplished using only one document. This clearly supports my conclusion that the subsection 85(1) rollovers of the partnership interests of each Appellant occurred one at a time and not simultaneously. I consider this clear and unequivocal evidence that, although the documents were dated the same day, the transfers occurred one at a time, even though moments apart. For example, I assume William transferred his interest in Varna to Lobro first. The result is that Harry [sic - the reference should be William] and Lobro Stables became the partners in Varna. Subsequently, by separate agreement, although only moments after, Harry executed a transfer document rolling his interest to Lobro Stables, which has now acquired the entire partnership interest. Subsection 98(5) contemplates this type of situation where one partner continues to carry on the business of the former partnership when the other partner has left. Pursuant to subsection 98(5) the partner carrying on the business of the former partnership acquires the assets of the former partnership at cost base. In drafting two separate documents, I believe it is easily inferred that this was clearly part of the overall design that this tax plan was intended to reflect. Otherwise everything would have been included in the one agreement as occurred with the subsequent transfer to Lobro Stables. Thus the rollovers are technically valid." Application of GAAR The Appellants conceded that a tax benefit arose by using Lossco. They also conceded that there was a series of transactions. However, they argued that there was no misuse of the relevant provisions of the Act or an abuse of the provisions of the Act as a whole. On the other hand, the Crown alleged that the proper approach in determining whether the transactions were undertaken for a purpose other than a tax benefit was to look at the individual transactions that made up the series. With respect to the misuse or abuse argument, the Crown submitted that when the policy is clear there is no need to refer to extrinsic evidence to establish the object and spirit of the provisions. In the Crown's view the policy behind paragraph 85(1.1)(f) was that the rollover of real property inventory is prohibited. By using the indirect partnership rollover approach, the Appellant misused those provisions with the result that section 245 should apply to deny the rollovers and the profit realized should be included in the income of the taxpayers, rather than Lossco. Justice Campbell started with a determination of the primary purpose of the transaction or series. If the primary purpose was to obtain a tax benefit, then there was an avoidance transaction. The Crown argued that each transaction within the series had to be analyzed and if the primary purpose of any one of the transactions within the series was to obtain the tax benefit, then it would be considered an avoidance transaction under subsection 245(3). The taxpayers contended that the series of transactions as a whole should be looked at to determine the purpose behind those transactions, citing The Queen vs. Canadian Pacific Limited. Justice Campbell did not completely accept the Appellant's approach; his view was that Canadian Pacific said that one transaction within a series cannot be further divided into separate components for the purpose of finding one of those components to be an avoidance transaction. Three transactions occurred on November 30th, 1993. According to OSFC Holdings, it is necessary to analyze the primary purpose of all the relevant transactions in the series. The primary purpose of each transaction must be determined on the facts at the time the transaction occurred. Justice Campbell cited Rothstein's comments at paragraph 46: "the words "may reasonably be considered to have been undertaken or arranged" in subsection 245(3) indicates that the primary purpose test is an objective one. Therefore the focus will be on the relevant facts and circumstances and not on statements of intention. It is also apparent that the primary purpose is to be determined at the time the transactions in question were undertaken. It is not a hindsight assessment ..." Justice Campbell acknowledged that the most direct route for the transfer of the property would have been from the taxpayers to the purchaser directly. However, it was clear that a more beneficial result would arise if the Appellants could access the losses in Lobro Stables. Those losses had been legitimately accumulated. Accessing those losses could not be accomplished directly because of the prohibition in paragraph 85(1.1)(f) against the rollover of real property inventory to a corporation. However, using a partnership, the taxpayers could transfer their interest in the property to the partnership and could then transfer the partnership interest to Lossco. On the issue of misuse and abuse, Justice Campbell turned to determining which provisions were being misused. Both subsections 97(2) and 85(1) were being used. Section 85 allows a rollover of certain types of property to a corporation. Subsection 97(2) differs materially from subsection 85(1) in that there is no prohibition against real property inventory being transferred at cost. To determine the existence of misuse, the first step is to determine the policy behind the provision. Misuse depends upon the object and spirit of the particular provisions, being section 97 and 85 in this case. Not surprisingly, the taxpayers asserted that there was no misuse as there was no violation of the policy behind the real property inventory restriction, which is to prevent a trader in real property from converting income into capital gains by rolling property into a corporation and then selling shares of the corporation. The Respondent argued that the misuse of 97(2) allowed the Appellants to avoid a gain that should otherwise have been included in income. The Crown counsel did not demonstrate a clear and unambiguous policy behind the differences between section 85(1) and 97(2). Justice Campbell comments: "With nothing more from the respondent than a reformulation of what the provisions state, I could simply conclude that there is no misuse. However, Appellant's counsel referred me to outside material to ascertain the policy." The Appellants produced commentary from Professor Krishna and the Stikeman tax service to support the proposition that the policy behind paragraph 85(1.1)(f) is to prevent a real property trader from converting income into capital gains. Justice Campbell then posed the critical question: "In the facts before me does the tax planning convert business income to capital gains? Clearly that did not occur here. The transfer to the Varna partnership resulted in reporting of taxable business income as did the transfer of the partnership interest to Lobro Stables. And ultimately, in the disposition by Lobro Stables to 642388, the gain was reported as business income. Proof of this is reflected in the tax returns and in the evidence of Mr. Hill. There is no conversion of business income to capital gains here. It seems to me that this view is much more consistent with the policy objectives behind the provisions." Justice Campbell concluded: "When I looked at the particular facts of this case, they suggest no misuse of the provisions of the Act. The purpose behind the exclusion of land inventory from the definition of "eligible property" in subsection 85(1.1) is to prevent a taxpayer from converting what would otherwise be income into capital gains by using subsection 85(1). Here the gain on the sale of the Harrison property was reported as income and not as capital gain. Therefore the policy behind the provisions has not been violated and as a corollary, there is no misuse. The final matter in the GAAR analysis is whether there has been an abuse of the provisions of the Act as a whole." On this point, the Respondent argued that the general policy of the Act prohibits loss trading subject to certain exceptions. Further, Crown counsel argued that the term "loss" is interchangeable with the term "profit" and deduced that profit trading was therefore prohibited under the Act. Justice Campbell did not buy the argument: "From my reading, I do not see how the Respondent can glean any remarks that support the proposition that profit sharing is prohibited. I also believe that his interpretation of OFSC Holdings Ltd. is flawed. Clearly OFSC Holdings Ltd. prohibits loss trading. However, I would not extend the principles enunciated in OFSC Holdings Ltd. with respect to loss trading to conclude that profit trading is interchangeable with loss trading. There is nothing in OFSC Holdings Ltd. that even hints at such substitution." Justice Campbell then referred to discussion from Krishna, and Information Circular 88-2 outlining the General Anti-Avoidance Rule, to conclude that profit trading within a controlled group is an acceptable practice. He concluded that the general rule against loss trading has no equivalent rule when it comes to profit trading. Justice Campbell affirmed the concept that taxpayers are free to structure their transactions in a tax effective manner, to reduce tax otherwise payable, concluding: "the Appellant struck a deal with a long-standing business partner. The first place they contacted was their tax advisors' office. He used the provisions of the Act in conjunction with a pre-existing partnership and corporations to structure the Appellant's agreement with Drewlo [the ultimate purchaser] in the most tax efficient manner. The transactions were in accordance with normal business practice and were entered into for a bona fide purposes... This does not amount to a misuse or abuse of the provisions of the Act. It is simply utilizing them for the very purpose for which they were designed." Conclusions While this case has an encouraging result, it may be limited in its application. It now seems clear that using existing business structures to transfer profits into a loss company is acceptable tax planning. If some measure of income is triggered as part of that transfer process, it will be more difficult for CCRA to assert that the provisions of the Act have been misused or abused. It seems likely that GAAR would apply if real estate was transferred first to a newly formed partnership created for the sole purpose of receiving the property, that transfer was followed by the incorporation of the partnership and the shares of that recipient corporation were subsequently sold. That likelihood might decrease if the profit on the sale of those shares was reported as income. However, the CCRA might not have to resort to GAAR if a newly formed partnership was used. Instead, CCRA might challenge the existence of the partnership on the basis that it was not carrying on a business or that there was no common intention (following the logic of McKeown) to carry on the business with a view to profit, since the entire intention was to collapse the partnership as soon as possible. The response to the "no business" challenge might be that the flip of the property was an adventure in the nature of trade, and therefore a business. A response to the "common intent" argument might be more difficult. II. Using Partnerships in Estate Plans Taxpayers and their advisers are comfortable using corporations in estate planning. Trusts have always had a place in the planner's inventory. Even special purpose entities, such as charitable organizations and foundations, have found their way into the estate planning universe. Partnerships, on the other hand, seem to be an under utilized planning vehicle. There may be several reasons why partnerships are not widely used. First, there seems to be a misconception within CCRA that partnerships are only vehicles for tax avoidance, and should be challenged as a matter of course. While the conduit feature of a partnership is uniquely suited for tax incentive structures, there are many valid commercial reasons for establishing them as part of a business or personal succession plan. Fear of a CCRA audit should not curtail effective succession planning. Second, partnerships have traditionally not been used as commercial business vehicles. While partnerships have long been the vehicle of choice for the professions, business people have traditionally sought the liability protection of a corporation. However, the advent of limited partnerships, and even stranger entities such as limited liability companies and income trusts, may slowly inspire more businesses to adopt a conduit structure. A corollary problem is a lack of understanding of how partnerships work. Business people and their advisors understand corporations. They understand the distinction between shareholders and managers. They understand corporate governance. They understand the difference between dividends, capital gains and employment income. They appreciate the concepts of shareholder rights and directors' duties. These concepts do not apply to partnerships, and the unfamiliarity of partnership concepts may deter their use. Some of the commercial advantages of using partnerships are discussed below. This list is by no means exhaustive; as one becomes more comfortable with using partnerships, additional benefits (and disadvantages as well) appear. Rollover of Real Estate Inventory A common problem in estate and business planning is real estate. Where the real estate is clearly a capital asset, it qualifies as "eligible property" for the purposes of a section 85 rollover. However, in many cases there may be a "secondary intent" behind the original acquisition of the property, or its use may have changed over time, or for other reasons there may be doubt as to whether is qualifies as eligible property. Where a rollover to a corporation would be denied, the property can still be transferred on a tax deferred basis to a partnership. Although an immediate subsequent transfer to a corporation might attract GAAR (as outlined in paragraph 22 of Information Circular 882), in circumstances where there is no attempt to convert income into capital gains, it might be possible to either incorporate the partnership business or transfer the partnership interests to a corporation on a tax deferred basis. For instance, in Loyens (discussed above), the taxpayers transferred real estate through an existing partnership they operated to a loss corporation which they also operated. The income realized by the loss corporation on its resale of the land was offset by its loss carryforwards. The Tax Court concluded that "the transactions were in accordance with normal business practice and were entered into for a bona fide purpose….This does not amount to a misuse or abuse of the provisions of the Act. It is simply utilizing them for the very purpose for with they were designed." Rollovers, Part Two - Dealing with inherent tax liabilities When a taxpayer transfers an asset into a corporation, accepted practice is that the fair market value of the asset is not reduced by any inherent tax liability. For instance, when a taxpayer transfers an asset with a cost of $100 but a fair market value of $400, the transfer value for the purposes of the section 85 rollover (and in particular, for the purposes of determining whether a gift has been conferred under paragraph 85(1)(e.2)) is not reduced by any potential tax on the latent gain. Thus the inherent tax liability is shared by all shareholders. However, if an asset is transferred into a partnership, the pregnant tax liability can be allocated back to the original transferor. Thus the other partners will pay tax only on the true appreciation in the value of the asset over the transfer value, and not on the latent gains. For instance, if a taxpayer were to transfer an asset into a partnership with a cost of $100 but a fair value of $400, the transferor's partnership capital account could be credited with $400. However, the partnership agreement could also provide that any capital gain or recapture arising on the sale of the particular asset, up to the transfer price, could be allocated back to the original transferee partner. The other partners would only share tax on the appreciation in the value beyond the original fair market value transfer price. Would such an allocation provision under a partnership agreement, which effectively transfers tax liability back to the person who transferred it to the partnership, be considered unreasonable for the purposes of section 103? Is it likely that "the principal reason for the agreement may reasonably be considered to be the reduction or postponement of the tax that might otherwise been or become payable under [the] Act…" for the purposes of subsection 103(1)? Or is the intent of such a provision to allocate economic costs and benefits among the partners? Is such an agreement to share income or gains "reasonable in the circumstances having regard to the capital invested…" to preclude the reallocation of income or gain under subsection 103(2)? Governance Partnership is a relationship between partners. It is quasi-contractual, the contract among the partners being the partnership agreement. The various provincial partnership acts generally codify common law, with a few notable improvements (one of the most significant being the presumption of continued existence following changes in membership of the partnership). There is a presumption of equality among partners (easily rebutted), unlike the distinction between shareholders and officers and directors of a corporation. Unlike the statutory protections accorded minority shareholders, what few protections accorded partners under common law can be over-ridden by the express terms of the partnership agreement. Consequently, partnership agreements can impose onerous terms on minority partners, or on partners whose conduct prejudices the partnership (a classic example is a provision in many tax shelter limited partnership agreements that effectively expropriates a limited partner's units if that partner ceases to be resident in Canada). The partnership agreement can also create different classes of partners (equity partners, income partners, partners with special rights). Unlike shareholders of a corporation, such partners have no special statutory rights because of their status (for instance, the right to vote as a separate class on fundamental matters). Another advantage to the partnership structure is anonymity. There are minimal government and regulatory filings for partnerships. There are no statutory requirements for annual meetings, audited financial statements, annual information returns or member communications (annual reports and management discussion and analysis of performance). The partnership agreement generally defines the disclosure to partners. Flexibility - Compensation Under the classic corporate estate plan, the incoming "beneficiary investors" (usually family members) will subscribe for growth shares for a nominal amount. If these investors become participants in the business, they will probably become employees of the corporate freeze company or its operating subsidiary. Their specific duties, job expectations and anticipated compensation should be spelled out in either shareholder agreements or employment or consulting agreements with the operating entity. However, in many cases, no such agreements will be created or implemented. Once the compensation package is created, it becomes part of the employment contract, and subsequent variations can give rise to potential problems or even litigation. For instance, if two siblings are introduced into the business as operating managers and their compensation is established at $80,000 per annum, that compensation becomes an integral part of their employment agreement. There are never any difficulties in declaring bonuses or increasing the compensation package (other than the normal operating issues of rising expectations). Down the road, if one of these managers succeeds, while the other does not, it may be difficult to adjust the compensation scheme unless there are contracts in place that specifically allow changes. However, should one of the managers not work out and the company attempt to change duties or reduce the compensation payable, the company may be open to a law suit for constructive dismissal. If the non-performing manager holds shares, there may be difficulties in reclaiming his or her equity interest. In the absence of repurchase rights in a shareholders agreement, or specific provisions in the share provisions, the corporation will have no right to repurchase or redeem the shares held by the non-performing (or former) manager. Not only might the corporation have a disgruntled (former) employee, it might have a disgruntled continuing minority shareholder, potentially prepared to enforce all statutory rights. On the other hand, a partnership agreement would typically provide that the compensation to the partners will be determined periodically (usually annually), generally by the managing partner or consensus of the partners. This provides the flexibility to increase the income attributable to performing partners while reducing the share allocated to non-performing partners. Since partners are by definition not employees, there can be no claim for wrongful termination if a non-performing partner finds his allocated share of income, or his capital, decreasing over time. The partnership agreement might even expressly deal with terminating partners (a concept well known to professional firms!). Flexibility - Tracking Business Lines If the compensation for an employee or the return on investment for an investor is to be tied to the success of a particular business activity, the partnership structure offers more flexibility and simplicity. Although employment contracts can tie bonuses (or even base compensation) to the operating results of a particular business activity fairly simply, it is more difficult to direct a return on an equity investment. If the particular business line is profitable, but other businesses carried on by the corporation are not, the directors must consider the best interests of the corporation in determining whether to pay dividends to the investor backing the profitable business. Notwithstanding the success of the particular business, the overall corporate results might preclude either the repayment of dividends or the repurchase of shares, thereby denying the investor the anticipated returns. There are no comparable restrictions in a partnership. If the partnership carries on several businesses, the partnership agreement can define how the income, gains or losses from those separate businesses are to be allocated among the partners (probably by creating different classes of partnership interests). This could even extend to allocating the income earned by one business line to one set of partners, while allocating the losses generated by another business line to a different set of partners. Such allocations must be commercially reasonable to prevent attack under section 103. Note that there are no solvency restrictions applicable to partnerships. While the directors of a corporation must ensure that the corporation is solvent at the time dividends are paid (to protect its creditors), partners are always exposed to claims of creditors when they receive distributions from the partnership. Since a creditor could demand that a partner repay a distribution it received, there is an automatic, but indirect, implicit solvency test. Flexibility - Earn-ins, Thaws and Refreezes One of the common concerns in estate planning is determining which member of the "beneficiary" generation is likely to grow into managing the business. As noted above under "Compensation", some beneficiaries may grow into the business while others who started well might ultimately prove to be incapable managers. How can the estate plan "self-correct"? A partnership can accommodate this type of business evolution better than a corporation. As noted above, the relative income (and ultimately capital) interests in a partnership can naturally evolve to reflect the success or failure of different partners. For instance, if the eldest child first evinces an interest in the business, while the youngest shows no interest, the eldest could start with a larger partnership interest and the youngest a smaller. If the youngest became interested and involved with the partnership business, his or her interest could grow over time to reflect the increasing participation in and contribution to the business. The same process could be adapted to allow a freezor to enhance its interest in the partnership (a "thaw") or to alter the fundamental economic interests of the various participants. Such changes could be anticipated in the original partnership agreement (i.e. the partnership agreement could specify a process to accomplish this goal) or the members could agree to modify the partnership agreement, just as they would modify any other contract. Flexibility - Protecting the Economic Interests of the Freezor This could be the reverse of the point above. Under a partnership freeze, the freezor would hold some form of limited partnership interest. The "beneficiaries" would likely hold another class of limited partnership interest, rather than general partnership interests (which would expose them to general liability). However, as operators, they would be officers and directors of the general partner. It would not be unreasonable for the limited partners to have limited rights to replace the general partner if it proved incapable of managing the business. If the attempt to transfer the growth of the business to the "beneficiaries" was unsuccessful, the freezor limited partner might exercise its right to replace the general partner with one which it controlled. As part of this process, the freezor might be entitled to an enhanced interest in the partnership profits or capital - all as provided in the partnership agreement. III. Update on Tax Shelters Two significant tax shelter decisions have been delivered this year. Although not all the issues affecting tax shelters have been resolved, there now seems to be reason to believe that the backlog of tax shelter objections can be resolved. The first of the major tax shelter cases to reach the courts was Peter Brown vs. The Queen12. Mr. Brown was a general partner in a general partnership which had acquired cartridge computer games. In challenging the CCA based deductions, the CCRA threw all the predictable arguments at the taxpayer - no partnership, property not available for use, no reasonable expectation of profit, contingent liability, future benefit which reduced the at risk amount, valuation, and non-arm's length nature of the transaction. Although the taxpayer won most of the technical issues, he lost on the major economic issues - valuation, at risk amount, and arm's length transaction. One of the taxpayer's arguments was that the purchase transaction between the general partnership and the vendor of the software was arm's length. If the taxpayer had been able to maintain this, the anticipated result would have been that the value agreed to by these arm's length parties could not be impugned by the CCRA. The taxpayer was unsuccessful. The Federal Court of Appeal concluded that the entire transaction had only one common directing mind, so that the partnership and the vendor were not dealing at arm's length, thus opening the door for the CCRA challenge to the value of the software. Note that a similar argument was used in the McCoy case (discussed below), where Justice Bowman agreed that the parties were arm's length, but did not find this a compelling reason to accept a valuation which defied reason. The real problem the taxpayer faced in Brown was the application of subsection 96(2.4) which deemed the partners to be limited partners, thus making operative the at risk rules in subsection 96(2.2). After the partnership in Brown was created, as a general partnership, the partnership and the software vendor entered into an agreement under which the partners were entitled to "put" their partnership units back to the vendor at a future date (10 years after the transaction originated) for a specified amount. The Court of Appeal concluded that this agreement first had the effect of converting the general partners into limited partners for tax purposes, and then reduced their at risk amount to reflect this contingent future benefit. Consequently, the limited partners were entitled to claim deductions based on an amount lower than both the actual cash they had invested into the venture and the fair market value (as determined by the Tax Court) of the software. As an aside, the party who was to provide this benefit is no longer carrying on business, so the contingent benefit which created this tax problem will likely never materialize. In McCoy13 , the Minister also threw every conceivable argument at the taxpayer in disallowing the CCA based tax deductions. As Associate Chief Justice Bowman observed: "The appellant does not allege that the Minister did not act on all 79 assumptions pleaded and so I must accept that he did. However, it seems hard to believe that the Minister would have had the mental agility to base an assessment upon such a potpourri of contradictory and inconsistent assumptions." Justice Bowman felt that "the resolution of this case depends upon a determination of three or four relatively simple and straightforward issues." One of his first concerns was whether the partnership and the software vendors were dealing at arm's length. The controlling shareholder of the software vendors was not related to the partnership, whether one looked at the partners collectively or at the general partner. After reviewing the classic controlling mind cases (Sheldon's Engineering, Merrit Estate and Swiss Bank Corporation), Justice Bowman concluded that there was no control exercised by either party over the other, and no common mind, so that the parties were dealing at arm's length. He observed: "The statement that the parties did not have opposing interests but 'acted in concert' is either incorrect or does not lead to the conclusion that the parties were not at arm's length…. Mr. Furtak [the owner of the software vendors] and the partnership, acting through the general partner as represented by Mr. Coleman, each had their own interests - Mr. Furtak wanted the money and the partnership wanted the software which it was anticipated would yield income and also carry with it tax benefits. The evidence of Mr. Coleman was that there was a good deal of bargaining between him and Mr. Furtak about the price. To say that the parties acted in concert is not meaningful in this context. All it means is that both parties wanted to get the deal done. If that is the sort of "acting in concert" that results in parties to a transaction not dealing at arm's length, then no business transaction between independent persons would ever be at arm's length." Justice Bowman next turned to the at risk rules. Although he rejected the Crown's attempt to combine subsections 96(2.1) and (2.2) with section 143.2, he concluded that it was not necessary to consider their application: "The rules are obviously a type of anti-avoidance provision and are designed to ensure that limited partners and investors in tax shelters (which MarketVision is) are not permitted to deduct losses that as a realistic economic matter will not actually or potentially hit them in the pocketbook. If the way the investment is structured results in the true cost being only the cash that the investor has put at risk it is unnecessary to consider the application of rules that achieve that result in any event. If the mischief that an anti-avoidance rule is designed to cure has already been eliminated by the way the transaction is set up there is no need to consider whether the rule might have operated to prevent the mischief if the inherent structure of the deal had not already done so." The next issue was whether the promissory notes issued by the investors to the software vendors were contingent. The Crown's position was that the notes were contingent because of the software vendors' warranty of a return and the guarantee of a certain number of trading report fees. On this point, Justice Bowman commented: "The obligation under the promissory notes to pay principal and interest does not depend on Trafalgar living up to its commitments under the Software Acquisition Agreement even though the partnership might have had a cause of action against Trafalgar." The Crown argued that the contingency which he contended attached to the Acquisition Note (the original promissory note issued by the partnership to the vendors) as a result of the various obligations, representations and warranties given to the partnership by Trafalgar were, after the extinguishment of the Acquisition Note by the assignment of the partners' promissory notes, transferred to the partners' promissory note. Justice Bowman did not believe this argument was correct as a matter of law. The partners' promissory notes remained absolute on their face. The real issue, according to Justice Bowman, was whether it was reasonable for the partnership to claim CCA on the basis of a purchase price that had not been paid in full. He concludes: "The answer to this question requires a determination of the true cost to the partnership of the software. The obvious starting point is the cash that was paid… What else was paid? The Acquisition Note … existed for a split second until it was paid off and replaced by the partners' promissory notes. The question is not whether those notes were contingent. They were not. The real question is: what were those notes worth?" After discussing the various obligations of the various parties to the transaction, Justice Bowman observes: "… I do not see how it can reasonably be considered that these notes have a value equal to their face amount when they are inextricably connected with obligations, real or assumed, by the holder. It would be naïve to assume that Trafalgar could demand payment of the notes at maturity and expect to receive a cheque by return mail. Any attempt to enforce payment of the notes would be met by a myriad of defences." In fact, shortly after the initial decision was handed down, additional reasons dated September 20, 2003 were issued, showing that the taxpayers and CCRA had agreed that the notes had a value equal to 15% of their face amount.14 This decision is good news for many taxpayers who purchased tax shelters years ago and whose appeals have been put on hold while test cases proceed through the courts. Justice Bowman's approach is practical and realistic, forcing taxpayers and CCRA to negotiate reasonable values rather than forcing judges (who are not valuators) to take up valuable court time senselessly. Only one issue remained, but it was not argued. If the value of the notes provided by the partners is less than their face amount, and that value plus the cash paid to the vendor becomes the cost of the software for CCA purposes, how should the difference between the face amount of the partner notes and their value be treated? If those notes were not ultimately paid off, but were forgiven, logically section 80 should only apply to that part of the "value" which was forgiven, since only that amount was previously recognized for tax purposes. In other words, if the face value of the note is $100, but its true value is only $15, and that $15 is the amount included in the cost of the software, the true purchase price paid by the partner would be the cash component plus that value. Since the remaining $85 of the note was not recognized in the value of the property purchased, it should correspondingly not be recognized if the obligation to pay is forgiven. If $5 of the $15 "value" was paid, and the balance was forgiven, the forgiven amount for the purposes of section 80 should be only $10. Undoubtedly this point will be addressed in settlement discussions on many outstanding tax shelter appeals. The 6eed for Tax Shelter Identification 6umbers The tax shelter rules require that certain steps be taken before tax shelters can be sold, and before investors can claim deductions. Subsection 237.1(4) prohibits the sale of a tax shelter before the Minister has issued an identification number. Subsection 237.1(6) provides that no investor can claim deductions in respect of a tax shelter unless a prescribed form containing prescribed information is filed. Notwithstanding these clear rules, some promoters and their (unsuspecting?) investors fail to comply and suffer the consequences. In Maya Inc.15, the documentation clearly indicated that an investor could effectively deduct 99% of the investment, while being guaranteed a reimbursement of 70%. The Tax Court found this arrangement constituted a tax shelter and since it had not been registered, the promoter was liable to penalties under subsection 237.1(4). In Blier16, the Minister asserted that the taxpayers had sold interests in tax shelters without an identification number. The taxpayers adduced no evidence to show that the interests were not tax shelters, and failed to produce any evidence that they had acted with due diligence. Again, the penalties were confirmed. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 98 DTC 6501; [1998] 4 CTC 77 2 2002 DTC 6969; [2002] 3 CTC 439 3 2002 DTC 6960; [2002] 3 CTC 421 4 reported in the Knotia electronic service; not yet reported in Carswell or DTC 5 2003 TCC 677 6 [2003] 3 CTC 2345 7 2003 TCC 152; [2003] 3 CTC 2185 8 2001 DTC 511 (French); [2001] 4 CTC 2197 9 2003 TCC 343 102003 TCC 469; 2003 DTC 1011 112003 TCC 214; 2003 DTC 355; [2003] 3 CTC 2381 12 2003 DTC 5298;[2003] 3 CTC 351 (FCA) 13 2003 TCC 332; 2003 DTC 660 14 2003 TCC 508 15 2003 DTC 947 16 2003 DTC 970 This publication is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal or professional advice to any particular reader. Readers are cautioned to seek the professional advice of an experienced lawyer and/or accountant regarding their own specific circumstances. Readers can contact Robin directly at 905-940-0516 or by e-mail at rmacknight@wilsonvukelich.com.