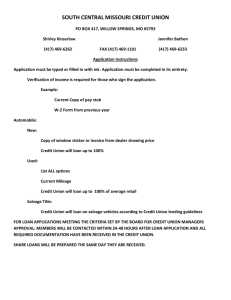

Authority and Information

advertisement