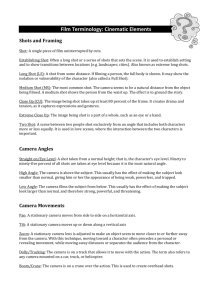

Shot by Shot - Chris McGuire

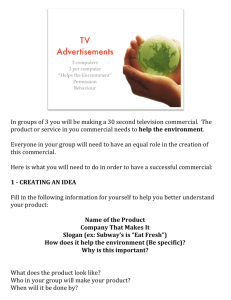

advertisement