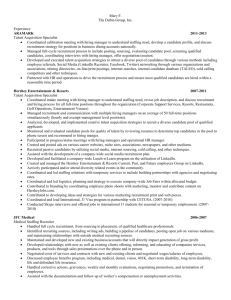

Chapter 04 - Duke University

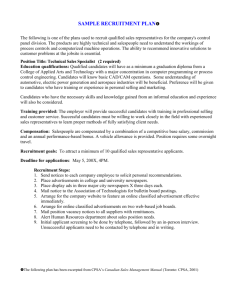

advertisement