The E-Payments Empire You Never Heard of

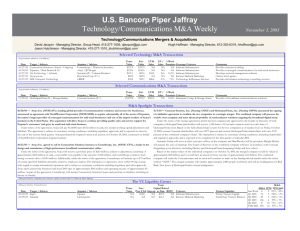

advertisement

The E-Payments Empire You Never Heard of Lauri Giesen With a clear-cut—and acquisitive—strategy for ATMs, prepaid cards, card-accepting merchants, and other implements of electronic transactions, U.S. Bancorp is in the driver’s seat as new payment forms chip away at cash and checks. While most other second-tier institutions have shed or outsourced much of their payments business, U.S. Bancorp has not only stayed in the game, but has taken an aggressive acquisition approach to increase its stake. Indeed, through acquisitions and continued investments in existing operations, U.S. Bank is not just a major player in a couple areas of the payments business, it is a top-10 player in just about every niche— including issuing both consumer credit and debit cards, issuing commercial cards, driving ATMs, serving as a merchant acquirer, helping serve the card-payment needs of smaller financial institutions, and issuing prepaid cards. “The industry as a whole has been in a consolidating mode and most banks the size of U.S. Bancorp have been targets of the big companies that are leading this consolidation movement,” says Edward Kountz, Boston-based senior analyst of financial services for JupiterResearch. “But U.S. Bancorp, instead of being a target, has been one of the consolidators and has been very successful at it.” While it might sound strange to describe as second tier a banking firm that boasts $213 billion in assets and ranks as the country’s sixth-largest bank, U.S. Bancorp’s size nonetheless pales when compared with the top three bank-holding companies: Citigroup Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., and Bank of America Corp., each of which has more than $1 trillion in assets. U.S. Bancorp is a league with such super-regional banks as Wachovia Corp., Wells Fargo & Co., and Fifth Third Bancorp, the latter two of which also have sizable footprints in payments. U.S. Bancorp has been able to prove that being a top payments player is more than just achieving status. In contrast to many banks, which are wary of what they view as a low-margin, tech-intensive business, it has shown that payments can be quite profitable. In the second quarter, for example, the Payment Services unit, one of U.S. Bancorp’s five major business lines and its fastest growing, reported income of $251 million, up 37% from $183 million in 2005’s second quarter, and accounted for 21% of the company’s $1.20 billion in earnings (chart, page 22). Payment Services’ return on equity grew to a healthy 21.2% from 18.3% in 2005’s second quarter. But U.S. Bancorp isn’t satisfied. With a foothold already in Canada and Europe through its Nova Information Systems merchant-acquiring operation, the bank plans to hit the Asia Pacific region in 2008. And it’s planning to push its prepaid card operations heavily in the next few years, including putting more emphasis on gift cards, payroll cards, and health-care cards. And, while U.S. Bank has been active in developing contactless payment solutions on the acquiring side of the business, the bank intends to invest in that emerging technology on the issuing side with a pilot program this fall. “I expect to see a lot of new things coming out of U.S. Bancorp in the next year in its payments-services, merchant-acquiring, and ATM operations,” says Brian Riley, senior analyst of bank cards for Needham, Mass.-based TowerGroup, an editorially independent subsidiary of MasterCard Inc. Payments Empire The current bank is the result of a number of mergers and acquisitions that occurred during the past 10 years involving banks that were already heavily committed to various aspects of the payments business (chart). “We were strong in payments going back to the four large banks that make up most of what is U.S. Bancorp today,” explains Pamela Joseph, U.S. Bancorp vice chairman who is also chairman and chief executive of Nova. “One of our early banks, First Bank of Minneapolis, established the payments business as part of its core focus. Early on, it was looking at how to move check processing into an electronic business.” Furthermore, First Bank System was one of the early innovators in the corporate card world—an important part of U.S. Bancorp’s payments business today as a major issuer of commercial credit and debit cards, purchasing cards and Voyager fleet cards. And the other three major predecessor banks—the former First Wisconsin (later Firstar), U.S. Bank of Portland, Ore., and Star Banc Corp. of Cincinnati—also made strong contributions to the payments business. Origins of a Payments Empire Under the banking brotherhood of Jerry A. and John F. “Jack” Grundhofer, a management team originating with Cincinnati’s Star Bank and the former First Bank System is now planted at U.S. Bank in Minneapolis, overseeing a vast empire of 2,400 branches in 24 states—and a payments powerhouse. 1990: John Grundhofer becomes chairman, president, and chief executive of Minneapolis-based First Bank System. First Bank System establishes itself as the leading issuer of Visa-branded corporate cards as well as a major merchant acquirer. 1993: Jerry Grundhofer, a veteran of Security Pacific Bank and Bank of America, becomes president and chief executive of Cincinnati-based Star Banc Corp. 1997: First Bank System buys Portland, Ore.-based U.S. Bancorp, a major regional acquirer. Headquarters remain in Minneapolis but the merged entity takes U.S. Bancorp’s corporate name as well as its U.S. Bank moniker for branches. 1998: Star buys Milwaukee-based Firstar Corp. (formerly First Wisconsin Corp.), takes Firstar name and moves headquarters to Milwaukee. First Wisconsin developed a large agent-bank network and the Elan payment-services brand. 2001: Firstar buys U.S. Bancorp, takes U.S. Bancorp name and moves headquarters to Minneapolis. Jerry Grundhofer named president and chief executive and John chairman until his retirement in late 2002. July 2006: Jerry Grundhofer announces plans to retire as chief executive in December, will remain chairman until the end of 2007. U.S. Bancorp president and chief operating officer Richard K. Davis is named successor. Davis joined Grundhofer in 1993 as Star Banc’s head of consumer banking. Major payments acquisitions: Fleet card provider Voyager Fleet Systems Inc. by U.S. Bancorp, 1999; merchant processor Nova Corp. by U.S. Bancorp, 2001; euroConex merchant business by Nova, 2004 (euroConex created as joint venture by Nova and Bank of Ireland in 2000); ATM/debit processor Genpass Inc. by U.S. Bancorp, 2005; merchant acquirer Citibank Card Acceptance (Europe) by euroConex, 2005; merchant acquirer First Horizon Merchant Services by Nova, 2006; freight transaction processor Schneider Payment Services by U.S. Bancorp, 2006. Selected bank acquisitions: Colorado National Bank, Denver, by First Bank System, 1993; Mercantile Bancorp., St. Louis, by Firstar, 1999. Source: U.S. Bancorp “First Wisconsin spent the last 25 years developing a business as an agent-bank card issuer for smaller institutions,” Joseph says. “That bank played an important role in helping small banks stay in the card business.” Add to that mix the strong ATM and electronic-banking capabilities of U.S. Bank and Star Banc, backed up by Nova and Nova’s recent acquisition of First Horizon Merchant Services, the merchant-acquiring unit of Memphis, Tenn.-based First Horizon National Corp.’s First Tennessee Bank that had 53,000 merchants and $25 billion in annual charge volume last year. The sum is a gigantic payments empire. “When the banks that make up U.S. Bancorp today came together, they brought assets that were fantastic in terms of helping the bank become a top-10 player in just about every segment of the payments business,” Joseph says. Today U.S. Bank boasts of being the second-largest independent driver of ATMs, the fifth-largest issuer of debit cards, the 10th-largest issuer of credit cards, the second-largest issuer of fleet cards, the secondlargest issuer of commercial cards after American Express Co., and the largest issuer of purchasing cards. The bank is also the third-largest merchant acquirer after Chase Paymentech Solutions and Bank of America Corp. “You have to have scale to stay in many of these businesses,” says Joseph. “If you’re not a top-10 player, you don’t have the scale necessary to stay in the business.” ’The Whole Package’ Gaining that scale meant keeping in-house many of the operations that other banks outsourced during the 1980s and ‘90s. “The industry trend is definitely to outsource everything,” says Jupiter’s Kountz. “But every time you have a trend, you always have one or two companies that go in the opposite direction. U.S. Bank is one of those one or two companies.” And while there can be danger in trying to be among the largest in so many different areas rather than pursuing a niche, the broad payments strategy seems to work for U.S. Bancorp, Kountz says. “They’ve seen the opportunity to be the Jack of Many Trades, which is a real challenge for a bank its size,” he says. “Yet it manages to do well in all its fields.” But while U.S. Bancorp has stayed in such businesses as processing card transactions and driving ATMs, the bank isn’t afraid to work with outside partners. It just wants to make sure it has control over the customer relationships. Indeed, several partnerships with outside companies have been successful in helping the bank with its cobranded credit and debit card programs. The bank works with Northwest Airlines Corp. and motorcycle manufacturer Harley-Davidson Inc., for example, to offer rewards cards that are marketed to customers of those organizations. Such cobranded marketing agreements help the bank reach beyond its traditional customer base for cross-selling other bank products. The cobranded debit card efforts are particularly important because to obtain a debit card with rewards targeted to their specific needs, customers have to open checking accounts with U.S. Bank. Having big partners in volatile industries such as airlines does carry some risk. Northwest is in bankruptcy, and according to a backgrounder U.S. Bank issued when it bought the First Horizon portfolio this year, airlines accounted for 17% of Nova’s charge volume in 2005, or approximately $22 billion. U.S. Bank wouldn’t confirm if Northwest is an acquiring client, but in a recent filing said it processes for “several airlines in the U.S.” When U.S. Bank works with other banks, it remains in the driver’s seat. It has 4,000 other financial institutions—primarily smaller banks and credit unions—for which it either drives ATMs or provides credit card services on an agent-bank basis, typically with the partner’s name on the front of the card but with U.S. Bank handling the processing and owning the receivables. Many of those financial institutions also use U.S. Bancorp for a host of services. “When we compete against [processing] companies like First Data or Total System, we have the benefit of being able to offer the whole package of services. We don’t just do credit card processing; we can drive their ATMs, issue credit cards, debit cards, and corporate cards,” Joseph says. U.S. Bank’s Payment Business (assets and merchant volume and transactions in billions; cards and accounts in millions) Assets $213 Branches 2,434 ATMs 4,966 ATMs driven 40,072 Merchants, U.S. 850,000 Merchants, foreign 125,000 Merchant charge volume (12 months ended June 30) $193.5 Merchant transactions (12 months ended June 30) 2.07 Credit card agent banks & credit unions 1,600 Consumer credit card accounts 4.4 Credit card agent banks & credit unions 1,600* Consumer debit card accounts 5.9 Commercial cards in issue 1.5 Voyager fleet cards in issue (2005) 1.6 *Amounting to 1.1 million accounts. Source: U.S. Bancorp Selected Payment Services Financials (second-quarter noninterest income, in millions) 2006 2005 Change Credit & debit card revenue $201 $177 14% Corporate payment products $139 $120 16% ATM processing services $47 $42 12% Merchant processing services $253 $198 28% Net Income $251 $183 37% Source: U.S. Bancorp And the relatively small size of the typical agent bank mitigates the risk associated with the loss of a major client should that client take operations in-house or merge with another bank. “When [First Data] or Total loses someone like Chase because Chase decides to take processing in-house, that is a lot of business to replace,” notes Joseph. “We don’t have any customers that are so large that they would be hard to replace.” Besides cards, ATM driving for bank clients is an important business for U.S. Bank. The company boosted that business in 2005 with the acquisition of Genpass Inc., an Irving, Texas-based ATM service company. Not only did that acquisition give U.S. Bank additional volume and scale, but it also brought a network of 7,000 ATMs that were part of Genpass’ MoneyPass surcharge-free network. That means U.S. Bank now can offer its own customers more free ATMs to use, boosting the value of its retail banking business. Plus, the bank can offer other banks the ability to let their customers to use these surcharge-free ATMs if those banks sign up for U.S. Bancorp’s ATM-driving service. “Genpass is an example of a well-thought-out acquisition,” says TowerGroup’s Riley. “MoneyPass grew the bank’s surcharge-free network from 5,000 ATMs to 12,000. That gives the bank a really nice penetration on which to work off of.” No Slam Dunk And while most American acquirers see little value in the fragmented European market, Joseph says you can’t view the world that way anymore. “We became international by default. With the advent of the Internet, payments have to be viewed as an international business. Retailers today need payments processors with multi-currency and multi-lingual capabilities regardless of where they are located,” she explains. Through Nova’s euroConex partnership with the Bank of Ireland in the merchant-acquiring business, U.S. Bank began forming partnerships with banks and retailers in Europe for merchant processing. The bank now handles payment transactions in 18 countries with plans to expand into more countries on that continent. “Most retailers in Europe are used to having to deal with a different processor for each country. We have been able to go to them and say we can process for all your operations in 18 different countries. That is a really good footprint to work off of,” Joseph says. While expanding the European operations will be the focus of U.S. Bancorp’s international efforts for the next 18 to 24 months, the bank also expects to hit Asia and the Pacific eventually. Joseph says U.S. Bancorp is talking to potential partners in that region, but believes it will be a few years before the company gets around to acting on those plans. “There is so much opportunity in Europe right now, we’ll probably need to spend most of 2006 and 2007 there,” she says. “Unless we find an exceptional deal, we won’t be able to look to Asia before 2008.” Riley believes the international moves are smart ones to make. “The U.S. acquiring market right now is dominated by five vendors,” he says. “There really are no more companies left that you can buy that will grow your operations significantly. The only way to grow now is to go beyond the U.S. borders.” That will be no slam dunk, however. The bank’s international success will still need to be proven and Jupiter’s Kountz adds, “getting a sizeable global footprint is not easy nor is it cheap.” Pushing Prepaid But not all growth is tied to operations outside the U.S. Joseph sees a lot of potential in the U.S. prepaid card market as well, including gift cards (U.S. Bancorp said it issued its 10 millionth gift card in July), payroll cards, and plastic tied to health-savings accounts (HSAs). Having so many surcharge-free ATMs will be important to U.S. Bank’s payroll card operations because employees of the companies that enroll for the card will be able to use it at all those ATMs without worrying about paying additional fees. U.S. Bank also hopes to leverage its merchant-acquiring business as a means to cross-sell payroll cards. While the bank’s treasury-management staff had been selling that product to the bank’s corporate customers, Joseph says there also is an opportunity for the merchant card unit to cross-sell its customers on the idea of issuing payroll cards to their employees. “Our next focus will be to sell our merchant base on the idea of payroll cards,” she says. “Restaurants, for example, have a lot of unbanked employees who would benefit from the cards.” U.S. Bancorp plans to push gift and HSA cards harder in the coming year, Joseph says. The latter offering is expected to integrate the payments product into the bank’s wealth-management business unit. By offering a card that can access funds that consumers set aside for their future health-care needs, Joseph hopes to show how the payments operations can assist the efforts of another area of the bank’s operations. ”We’ll create the products and the processes for health-care cards and the wealth-management staff will sell it to their clients,” she says. Meanwhile, U.S. Bancorp also is eyeing the emerging contactless payment business. While it has already worked with Visa and MasterCard on the acquiring side by helping merchant customers accept contactless cards as part of pilot programs established by the card associations, the bank has yet to become involved in the issuing side. But that won’t be long in coming. Joseph expects the bank to begin piloting a contactless program in an as-yet unidentified region of the country. The pilot is expected to be announced in early fall, she says. “This has always been a chicken-and-egg situation where consumers won’t ask for a contactless card because there are not enough places to use it and merchants won’t invest in the infrastructure to accept the cards because there aren’t enough cards in the market,” she says. “But we think we can overcome that by using the scale we have on both sides. We’ll pick a market where we think we can quickly saturate both sides of the equation.” To be sure, U.S. Bancorp has to execute when it comes to its new strategies for international payments, prepaid cards, and contactless transactions. And it’s up against heavy-duty competition in all of these markets. But it’s hard not to hear an empire-builder’s ring of confidence in the way Joseph speaks.