2.2 Capital management

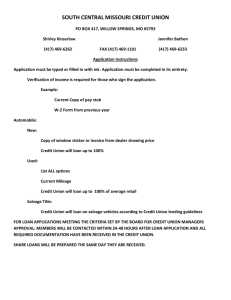

advertisement