Cash Cycle … Who's Managing It

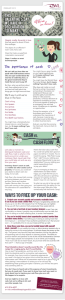

advertisement

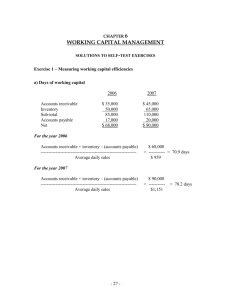

Cash Cycle … Who’s Managing It? Cash is, without a doubt, the life-blood of a business! Unfortunately, rapidly changing conditions impact cash and the amount a company has invested in its own cash cycle. Yet, so many business owners neither know how much they have invested in their cash cycle or how to manage it well. A company’s cash cycle is a measurement in days of the amount of cash a company has committed in its inventory, receivables and payables. The measurement in days reflects the effectiveness of management to minimize the time it takes to convert a dollar invested in inventory until it becomes a dollar collected from accounts receivable, while taking advantage of the free financing provided by suppliers in accounts payable. The primary goal is to reduce the number of the days in the cash cycle to the least possible without negatively affecting the business through inventory shortages or too stringent credit policies. The ultimate goal is a negative cash cycle thereby using suppliers’ money to finance daily operations In the petroleum marketer industry the cash cycle is acutely critical to monitor due to the volatile swings marketers experience during rapidly changing fuel prices, changes in their customers’ payment patterns, and the manner in which they pay their suppliers. Any or all of these can change quickly creating enormous burdens on companies to fund their cash cycle. It is critical that marketers know and understand the dynamic forces of the cash cycle and how to calculate and manage the cash they have invested in their company’s operations. To accurately calculate the cash cycle one must determine the number of days a company has cash invested in their cash cycle components: 1. Average Age of Inventory 2. Average Collection Period of Accounts Receivable 3. Average Payment Period of Accounts Payable The calculation of each of the cash cycle components for any twelve month period is as follows: 1. Inventory: [Inventory –divided by- (Cost of Goods Sold / 365)] 2. Accts. Rec.: [Accounts Receivable –divided by- (Sales / 365) 3. Accts Pay.: [Accounts Payable –divided by- (Cost of Goods Sold / 365) ] Note: Italicized section of the formula calculates the individual day volume for each component. By dividing the component by the individual day volume the number of days in each component is determined. The following format can used to assist management in the analysis of their company’s cash cycle for any twelve month period: Average Days In Row Inventory 1. Add Ending Inventory for the last 12 months and divide by 12 which equals: Average Ending Inventory. 2. Add Cost of Goods Sold for the last 12 months and divide by 365, which equals: Day of Cost of Goods. 3. Divide the answer of Row 1 by the answer of row 2, which equals: Average Days in Inventory Average Collection Days in Accounts Receivable Add Account Receivable for the last 12 months and divide by 12 which equals: Average Accounts Receivable Add Total Sales for the last 12 months and divide by 365, which equals: Day of Total Sales. Divide the answer of Row 1 by the answer of row 2, which equals: Average Collection Days Average Payment Days in Accounts Payable Add Accounts Payable for the last 12 months and divide by 12 which equals: Average Accounts Payable Add Cost of Goods Sold for the last 12 months and divide by 365, which equals: Day of Cost of Goods. Divide the answer of Row 1 by the answer of row 2, which equals: Average Payment Days In the chart that follows one can readily see the dynamic difference between the company’s investment in dollars in inventory and receivables versus the benefit it receives in the receipt of spontaneous, non-interest bearing debt from accounts payable suppliers. The number of days of free-money from accounts payable suppliers is a direct reduction against the number of days a company has its own cash committed in inventory and receivables. The sum of the company’s collection days and inventory holding days offset by the free-cash days provided by accounts payable suppliers determines the Net Cash Days in a company’s cash cycle. GRAPHIC CHART SHOWING RELATIONSHIP ENTERED HERE! Petroleum marketers have different cash cycles for different types of business models. One size does not fit all! Marketers with large sales volumes in wholesale commercial lubes and light fuels to commercial and industrial accounts and cardlocks will usually have much larger inventory and receivable days than a jobber whose business model consists of running company operated convenience stores or a company that primarily has supply contracts with dealers. The following four jobber business models were broadly defined to allow the reader the opportunity to better benchmark their specific type of distributorship: 1. Lubes: Heavy emphasis on commercial lubes and some wholesale fuel. 2. Dealers: Primary focus servicing dealers – predominately wholesale fuel. 3. Conv. Stores: Company-operated and/or leased convenience stores with light fuels. 4. Hybrid: Jobbership containing some of all of the above. Average Age of Inventory (Days) + Average Collection Period (Days) - Average Payment Period (Days) Net Cash Cycle Days Basic Four Petroleum Marketer Business Models 1 2 3 4 15.2 2.8 9.7 12.3 26.5 3.1 5.4 18.2 (28.5) (14.3) (13.1) (23.5) 13.2 (8.4) 2.0 7.0 The Net Cash Days presented in the chart above for each business model was obtained from marketers all around the country for the trailing twelve month period ended April 30, 2003. Their individual business model profiles were analyzed and sorted respectively. The respective cash cycles presented are not intended to be a definitive study of the types of business models available to marketers, or the relative advantages or disadvantages of each business model. The illustration is intended to provide a range of timely operating benchmarks from which to begin your company’s analysis. For is there any more critical asset to manage than … cash?