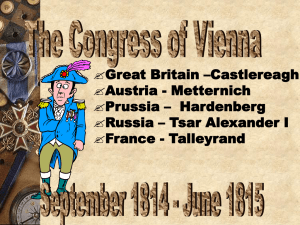

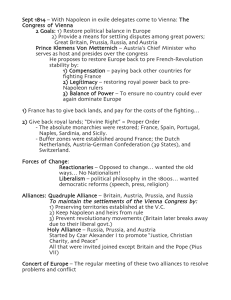

Conservative Order and National Independence

advertisement