- WW Norton & Company

advertisement

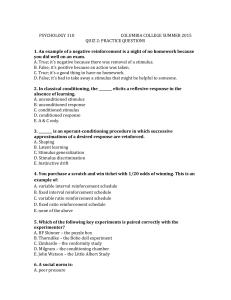

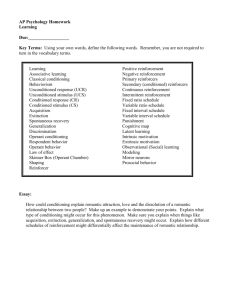

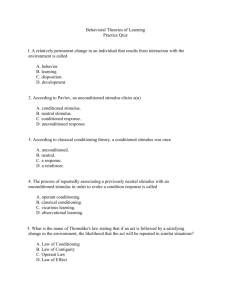

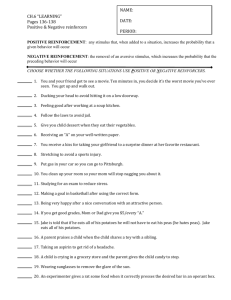

Chapter Six Summary 6.1 How Do We Learn? Learning Results from Experience: Learning is a relatively enduring change in behavior that results from experience. Learning enables animals to better adapt to the environment, and thus, it facilitates survival. There Are Three Types of Learning: The three major types of learning are nonassociative, associative, and observational. Nonassociative learning is a change in behavior after exposure to a single stimulus or event. Associative learning is the linking of two stimuli, or events. Observational learning is acquiring or changing a behavior after exposure to another individual performing that behavior. Habituation and Sensitization Are Simple Models of Learning: Habituation is a decrease in behavioral response after repeated exposure to a stimulus. Habituation occurs when the stimulus stops providing new information. Sensitization is an increase in behavioral response after exposure to a repeated stimulus. Sensitization may occur in cases where increased attention to a stimulus may prove beneficial, such as in dangerous or exciting situations. 6.2 How Do We Learn Predictive Associations? Behavioral Responses Are Conditioned: Pavlov established the principles of classical conditioning. Through classical conditioning, associations are made between two stimuli, such as the clicking of a metronome and the presence of food. What is learned is that one stimulus predicts another. Acquisition, second-order conditioning, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, discrimination, and blocking are processes associated with classical conditioning. Classical Conditioning Involves More Than Events Occurring at the Same Time: Not all stimuli are equally potent in producing conditioning. Animals are biologically prepared to make connections between stimuli that are potentially dangerous. This biological preparedness to fear specific objects helps animals avoid potential dangers, and thus it facilitates survival. Learning Involves Expectancies and Prediction: The Rescorla-Wagner theory describes how the strength of association between two stimuli depends on how unexpected or surprising the unconditioned stimulus is. Positive prediction error results when an unexpected stimulus is presented. Positive prediction error leads to high levels of learning. Negative prediction error results when an expected stimulus is missing. Negative prediction error promotes the extinction of learning. The neurotransmitter dopamine provides one neurobiological basis for prediction error. The release of dopamine increases after positive prediction error and decreases after negative prediction error. Phobias and Addictions Have Learned Components: Phobias are learned fear associations. Addictions are learned-reward associations. Classical conditioning and second-order conditioning can explain not only how people learn to associate the fearful stimulus or drug itself with the fear or reward but also a host of other “neutral” stimuli as well. In the case of drug addiction, addicts often inadvertently associate environmental aspects of the purchase and use of the drug with the pleasurable feelings produced by the drug. These learned associations are major factors in relapse, as seemingly innocuous stimuli can trigger cravings even years after drug use is discontinued. 6.3 How Does Operant Conditioning Change Behavior Reinforcement Increases Behavior: Reinforcement describes how consequences make behaviors more likely to occur. Shaping is a procedure in which successive approximations of a behavior are reinforced, leading to the desired behavior. Reinforcers may be primary (those that satisfy biological needs) or secondary (those that do not directly satisfy biological needs). Both positive and negative reinforcement increase the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated. In positive reinforcement, a pleasurable stimulus is delivered after a behavior (e.g., giving a dog a treat for sitting). In negative reinforcement, an aversive stimulus is removed after a behavior (e.g., letting a puppy out of its crate when it acts calmly). Operant Conditioning Is Influenced by Schedules of Reinforcement: Learning occurs in response to continuous reinforcement and partial reinforcement. Partial reinforcement may be delivered on a ratio schedule or an interval schedule. Each type of schedule may be fixed or variable. Partial reinforcement administered on a variable-ratio schedule is particularly resistant to extinction. Punishment Decreases Behavior: Punishment decreases the probability that a behavior will repeat. Positive punishment involves the administration of an aversive stimulus, such as a squirt of water in the face, to decrease behavior. Negative punishment involves the removal of an appetitive stimulus, such as money or the opportunity to drive the car, to decrease behavior. Positive punishment has been shown to be generally ineffective for changing behavior, since it can produce fear, anxiety, and inappropriate imitation of the punishing behavior. Behavior modification involves the use of operant conditioning to eliminate unwanted behaviors and replace them with desirable behaviors. Behavior modification programs work by reinforcing appropriate behaviors and ignoring inappropriate behaviors. Punishment, especially positive punishment, is not used in behavior modification programs because it rarely stops undesirable behavior. Biology and Cognition Influence Operant Conditioning: An animal’s biological makeup restricts the types of behaviors the animal can learn. Latent learning takes place without reinforcement. Latent learning may not influence behavior until a reinforcer is introduced. Dopamine Activity Underlies Reinforcement: The brain has specialized centers that produce pleasure when stimulated. Behaviors that activate these centers are reinforced. The nucleus accumbens has dopamine receptors, which are activated by pleasurable behaviors. Through conditioning, secondary reinforcers can also activate dopamine receptors. 6.4 How Does Watching Others Affect Learning? Learning Can Occur through Observation and Imitation: Observational learning is a powerful adaptive tool. Humans and other animals learn by watching the behavior of others. The imitation of observed behavior is referred to as modeling. Vicarious learning occurs when people learn about an action’s consequences by observing others being reinforced or punished for their behavior. Watching Violence in Media May Encourage Aggression: Media violence has been found to increase aggressive behavior, decrease prosocial behavior, and desensitize children to violence. Nonetheless, laboratory research may not simulate real-life exposure to violence in the media, and so further research is warranted. Fear Can Be Learned Through Observation: Monkeys have learned to fear snakes (but not flowers) by watching other monkeys react fearfully. These findings suggest that monkeys can learn by observation if the behavior is biologically adaptive. People also learn fear by observation, such as in learning to avoid a neighborhood because of news reports about crime in the area. People observing other people receive a painful shock experience activation in the amygdala—a brain area important for processing emotional responses, including fear—even though they themselves did not receive any shocks. Mirror Neurons Are Activated by Watching Others: Mirror neurons become activated when we observe others engaging in actions. In fact, the same neurons that become active when we observe another person engaging in a task become active when we perform the same task. Mirror neurons may be involved in learning about and predicting what others are thinking. They may also form the basis of empathy, the ability to understand the perspective of other people.