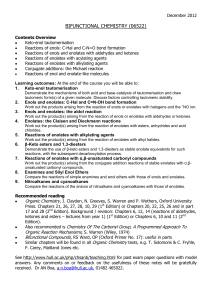

Enolate chemistry

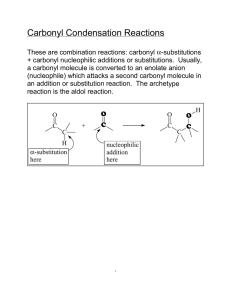

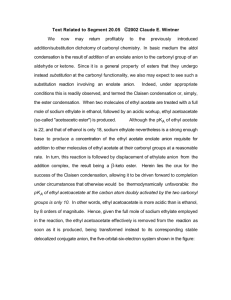

advertisement

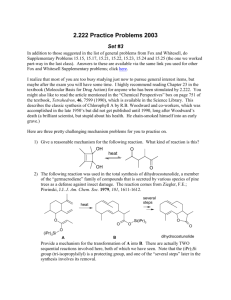

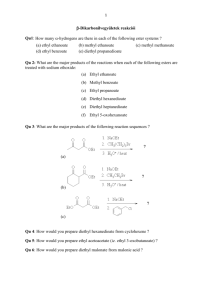

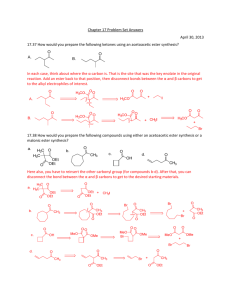

Enol/Enolate Alkylations. Enolization: R !+ ! O H2 C R' You should remember this picture from previous notes. The slight positive charge which develops on the carbonyl carbon does more than make it a good electrophile - it also “acidifies” the protons on the carbon next to it. In essence, it turns the pair of electrons in the π-bond into a good “leaving group” – even moderately weak bases can effect this transformation (sort of like an elimination): O! O + ! H H + H2 O H H H R R OH The product of this reaction is an enolate. Enols can form under acidic conditions, but because the carbonyl form is more thermodynamically stable, the enol is only present in tiny amounts: H+ H OH O O H H R H H H R H H H R O H H Enolates are stabilized by a mechanism similar to that of carboxylates - the negative charge is stabilized over two different atoms – in this case, both a carbon and an oxygen atom. This method of stabilization is present in both enols and enolates: O H O H OH H OH H H H H R R H R R In the presence of good electrophiles, a nucleophilic attack occurs, leading to substitution of the alpha carbon (the carbon next to the carbonyl group). O O H H R E+ H E R H The addition of electrophiles to the alpha carbon via the acid or base-induced formation of enols (or enolates) forms the bulk of the material of this chapter. Let’s begin with our first example. Reactions of Enols (i.e. Acidic conditions) Acid-Catalyzed Halogenation of Aldehydes and Ketones Our first example works under mild acidic conditions. Aldehydes can easily be monohalogenated at the alpha position by simply mixing the aldehyde with a halogen (usually Br2 or I2) and a trace of acid. IMPORTANT NOTE - if there are no alpha hydrogens, this reaction will not take place! O O + H H H H / Br2 H2O H Br O OH H H O H O O H H H O H H Br Br Br H O H2O / Br2 / HBr H H H H H O Br H2O / Br2 / HBr NO REACTION!!! Because the various enols possible are under equilibrating conditions, usually the MOST STABLE enol is the one formed in the highest consentration - and thus the one which reacts with the halide. For example, methyl cyclohexanone can form two different enols - the more highly substituted one is the most stable, and thus predominates: OH O O H2O / Br2 / HBr Br more stable OH less stable There are two major uses for these bromo-ketones and aldehydes. The first is elimination to form conjugated carbonyl compounds. This is a classic (and simple) method for preparing such compounds: O O warm pyridine H H H Br With cyclic ketones, these halogenated compounds can undergo what is called the Favorskii reaction. This is in essence a ring-contracting reaction, and usually proceeds in good yield. Time permitting, we will discuss this mechanism in class: O O Br OH 1) KOH 2) H3O+ The Hell-Volhard-Zelinskii Reaction As stated above, the acid-promoted alpha halogenation only works with aldehydes and ketones. What if you need to brominate a carboxylic acid? That’s where the HVZ reaction comes in. The reaction basically takes a difficult-to-enolize carboxylic acid, and first turns it into a much more enolizable acid bromide. This reaction produces HBr, which then assists in the alpha bromination of this acid bromide. Aqueous workup returns the acid bromide to the carboxylic acid state. Workup with an alcohol would, of course, produce the ester. O O 1) PBr3 / Br 2 R R OH (or OR') OH 2) H2O (or R'OH) Br Please remember that while this reaction can be used to form and ester, it cannot be used with an ester as starting material – you must start with the carboxylic acid! O O OH 1) PBr3 / Br 2 2) MeOH Br O OMe Hot Pyridine OMe Reactions of Enolates (i.e. basic conditions) Under sufficiently basic conditions, an enolate ion can be formed: O O B: H + BH C H H However, we must generally be careful with our choice of bases – if the base is also a good nucleophile, then attack at the carbonyl carbon becomes a more likely pathway. The most common bases used to form enolate ions are sodium hydride (very basic, non-nucleophilic) and Lithium Diisopropylamide (LDA, very bulky, thus non nucleophilic). Occasionally, hydroxide ion is used, but this is usually for very specific reactions (e.g. the haloform reaction). The enolate ion has two nonequivalent resonance forms (compare this with both the allyl anion and the carboxylate anion). The form where the charge is localized on the oxygen predominates (because of the electronegativity of oxygen), but the form with the charge localized on carbon is more nucleophilic, and is thus the form that typically reacts with electrophiles: E O O O E There are a few exceptions to this rule; generally acyl and silyl halides (TMS-Cl or CH3COCl) will react with the oxygen anion, to give silyl enol ethers and enol acetates, respectively. As you can see, alkylation of an enolate is a powerful tool for the formation of carboncarbon bonds under relatively mild conditions. Let’s explore this reaction a bit further. The Haloform Reaction: While enolates are great for forming new carbon-carbon bonds, the first reaction we’ll look at is a method for the destruction of a carbon-carbon bond. Essentially, the haloform reaction takes a methyl ketone (or a molecule which can be oxidized to a methyl ketone), and turns it into a carboxylic acid with one less carbon: O O I2 / NaOH + HCI3 R R O How does it work? As you probably expect, the enolate is formed, and is then halogenated. The protons on the halogenated compound are even more acidic, thus facilitating further enolization and halogenation. When the compound is fully halogenated (in this case, forming a CI3 group), there are no more acidic protons, so we look for the next possible mechanistic route: nucleophilic attack. Addition-elimination as shown leads to the carboxylate anion and a haloform (in this case, iodoform): O R H C H H O HO I O I R R O R C I I I No more acidic protons... HO HO O R C I C H H O I R I I O H CI3 + Alkylation of Enolates: Normal enolates formed by the action of LDA or NaH can generally be alkylated with alkyl iodides, bromides or tosylates, or benzylic or allylic halides. However, these reactions can sometimes be difficult to perform in high yield. A few methods do exist which allow enolate alkylations in high yield, and both take advantage of highly stabilized enolate anions: The Malonic Ester synthesis, and the Acetoacetic Ester synthesis. We’ll look at each of these in detail. The Malonic Ester Synthesis. Esters of malonic acid (in this case, diethyl malonate) are easily deprotonated to form the highly stabilized enolate (note sodium ethoxide is used as base – why not NaOMe?): EtO O O H H O NaOEt OEt O O EtO OEt O EtO O OEt EtO O OEt OEt As you can see, the negative charge is delocalized over one carbon and two oxygens - a very stable anion! The only significantly nucleophilic form is the one with the negative charge on the carbon, and this is the form that gets alkylated. You should note that there are two acidic protons on a malonic ester - thus it can be alkylated twice if desired. If an alkyl compound with two halogens is added, cyclic compounds can be formed. H (EtOOC)2C O EtO H 1) NaH 2)R-Br R (EtOOC)2C H R 1) NaH 2)R'-Br (EtOOC)2C O O 1) 2 NaOEt OEt 2) Br Cl EtO R' O OEt H H But the really cool thing about malonic esters (and acetoacetic esters, which we’ll see in a minute) is a reaction called decarboxylation. Once a malonic ester is hydrolyzed, then treated with acid, the two carbonyl groups interact, and through a 6-membered ring transition state (remember how organic molecules love to react through 6-membered ring - e.g. think of the Diels Alder reaction!), one of the carbonyl groups is blown off as CO2: H O O O O HO OH O OH NaOH EtO OEt O OH + CO2 Note that this is not a common reaction, and only happens with 1,3-dicarbonyl groups!!!!! Thus, malonic ester chemistry is an ideal way to make substituted acetic acids (which can then be converted to acid chlorides, and you should know all the types of reactions we can do with acid chlorides!). Let’s just look at another example: O O O O O O 1) NaOEt 1) NaOEt EtO OEt EtO OEt 2) Br EtO OEt 2) Br H H H O OH 1) NaOH 2) HCl / H2 O Acetoacetic Ester Synthesis The acetoacetic synthesis is almost exactly like the malonic ester synthesis – a 1,3dicarbonyl compound that is easily alkylated, and which also decarboxylates. But instead of making substituted acetic acid derivatives, this reaction makes substituted acetones. Just like in the malonic ester synthesis, the protons between the carbonyl groups are particularly acidic. They can be deprotonated with alkoxide (e.g. NaOEt), or sodium hydride, to yield the stabilized anion. Alkylation is also straightforward. The only difference comes in the decarboxylation step, where the only carboxyl group is lost to leave a methyl ketone: O O O O O 1) NaOEt HCl / H2 O OEt 2) CH I OEt 120°C 3 H H H Some things to note for both the acetoacetic ester and malonic ester synthesis (all of which are noted for the scheme below): O O O H OEt OEt O O EtO O C H O OEt O O EtO H EtO O HCl / H2 O 120°C H H O HO 1) These are highly stabilized anions, and will thus add to conjugated carbonyl compounds in a 1,4 fashion. Decarboxylation leads to the vinyl-substituted compound. 2) Saponiofication and decarboxylation can occur in one step - provided the temperature is high enough (usually, 110 - 120°C will do it). 3) Note that all esters in the molecule are saponified, but only the 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds can undergo decarboxylation. 4) As you’ll see in lecture, many different electron withdrawing groups can stabilize enolate charges, and lead to a large variety of different compounds. However, you’ll only get decarboxylation if you have at least one group that can be hydrolyzed to an acid, which is separated from another carbonyl group by one carbon. For example: O O O O O HCl / H2 O 1) NaH Br heat Br OEt 2) Br OEt Br Of course, this same ketone could be alkylated directly: O O 1) LDA Br 2) Br Br The product is the same, and there are fewer steps, but the reaction conditions are much more harsh. Furthermore, if we were not working with a symmetrical ketone, a mixture of products would result. Sometimes taking a few extra steps is worth it... O O O O O HCl / H2 O 1) NaH heat OEt 2) Br OEt O O 1) LDA O + 2) Br With simple esters and ketones, however, direct alkylation of the enolate is usually the way to go: O O O O 1) LDA OEt 1) LDA OEt 2) 2) Br I Notes: 1) These non-stabilized enolated are very basic - alkylation generally won’t happen with anything other than primary, allylic or benzylic halides. Secondary and tertiary halides will give elimination products... 2) Again, if there is more than one way to form the enolate, you’ll get a mixture of products...