Report on the 2008 UK 10-40 GHz Spectrum Auction

advertisement

Report on the 2008 UK 10-40 GHz Spectrum

Auction

Ian Jewitt and Zhiyun Li∗

September 2008.

Abstract

This paper reports on the outcome of the 2008 UK 10-40 GHz Spectrum Auction which was one of the first implementations of (a variant

of) the Clock-Proxy auction format as advocated by Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2006). The auction appeared to run smoothly and

achieve a reasonably efficient outcome. For some bidders their supplementary bids tended to make many of their bids effectively redundant.

The clock phase certainly lead to bidders focussing their attention on

a manageable number of feasible packages as intended. However, the

narrowness of this focussing, together with the redundant bids, reduced

measured opportunity costs and may have lead to low revenues.

1

Introduction

The format of the 2008 UK 10-40 GHz spectrum auction is a significant departure from the simultaneous ascending auctions which have typically been

used for spectrum assignments both within the UK and around the world.

The format can be viewed as a variant of the Clock-Proxy auction proposed

by Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2006). The hoped for advantages of the

format are summarised in the 2006 presentation (Ausubel, Cramton and

Milgrom (2006b)) as follows. The Clock Phase: takes linear prices as far

as they will go, providing simplicity and flexibility for the bidders; expands

substitution possibilities; minimises the scope for collusion; and eliminates

exposure and threshold problems. The Proxy Phase: leads to an outcome

in the core–efficiency with substantial seller revenues.

∗

The views expressed in this note are the authors’ own. This note was funded by

Ofcom.

1

Although this is not the first instance of a Clock-Proxy auction to assign spectrum, differences1 between this auction and the only previous one

we are aware of mean that there is likely to be substantial interest in the

performance of the format in this application.2

The UK 2008 10-40 GHz process departed from the Ausubel, Cramton

and Milgrom (2006) Clock Proxy format by having 3 rather than 2 distinct

bidding elements. The first two bidding elements took place in a primary

stage which is itself effectively a (variant of the) Clock Proxy format. The

purpose of this primary stage was to assign entitlements to quantities of

bandwidth in certain spectrum ranges. The third bidding element, the assignment stage determined how these entitlements were distributed over the

relevant spectrum.

The first bidding element in the primary stage is conducted via an ascending clock auction in which package bidding takes place–bidders commit

to prices for packages rather than their component parts. The second bidding element allows bidders to supplement their bids in the clock auction

with a possibly large number of simultaneous supplementary bids–again

these are on packages of lots. At the end of the primary bid stage the mechanism identifies the value maximising allocation consistent with the bids and

determines the base prices. Base prices are determined according to a modified ‘second-price’ or Vickrey rule which is computationally burdensome and

carried out on propriety Ofcom winner determination and pricing (WDP)

software. A modified, rather than pure Vickrey pricing rule is advocated,

in part, because Vickrey prices can lead to very low revenues for some configuration of reported preferences.3 The following example, adapted from

these references, illustrates. Figure 1 lists some hypothetical bid data in

1

Trinidad and Tobago undertook such an auction on 23 June 2005, Market Design

Incorporated advised. We have not been able to find details of the auction packaging

or bids, but it is clear that there are important differences between the Trinidad and

Tobago auction and the UK one. One difference is however aparent, the Trinidad and

Tobago process fixed in advance the number of possible concession holders: there were

to be two only. The clock phase of the auction determined which of the five qualified

entrants would get the concessions and also determine the minimum price of bandwidth

(See Telecommunications Authority of Trinidad and Tobago and Ausubel Cramton and

Milgrom (2006b)). The fact that an important part of the assignment, determining the

concession holders, is determined at the clock phase means that some of the features of

the UK 10-40 GHz auction which are stressed in our analysis would be masked.

2

Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2005) in response to the FCC’s Public Notice DA 051267 called for a variation in the FCC’s proposed schedule for testing alternative auction

models in favour of the Clock Proxy format.

3

See Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2006), Day and Milgrom (2007) and Day and

Raghavan (2007) for more details.

2

bidderID bidderName units_1 units_2 units_3 units_4 units_5 units_6 units_7 bidAmount

1 Bidder 1

0

0

1

1

0

0

0 1000000

2 Bidder 2

0

0

0

1

0

0

0 1000000

2 Bidder 2

0

0

1

1

0

0

0 1000000

3 Bidder 3

0

0

1

0

0

0

0 1000000

3 Bidder 3

0

0

1

1

0

0

0 1000000

Figure 1: Hypothetical bid data illustrating low Vickrey prices.

TieIDbidderIDbidderName units_1 units_2 units_3 units_4 units_5 units_6 units_7 bidAmountoppCost basePrice

1

2 Bidder 2

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

1000000

0

500000

1

3 Bidder 3

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

1000000

0

500000

Figure 2: WDP software output for the data in figure 1.

which there are 3 bidders; bidder one needs a unit of lots 3 and 4, bidders

2 and 3 only need one unit. The Vickrey prices are zero. It is clearly efficient to assign the lots to bidders 2 and 3 and a single lot is as valuable e.g.

to the coalition of bidder 1 and 2 as two lots would be. The opportunity

cost is zero as confirmed by the WDP software, see figure 2. Figure 2 also

displays the higher base prices which splits equally between bidders 2 and 3

the smallest amount they must pay so that the loser is unable to ‘offer’ the

auctioneer more for the two packages. To summarise, one of the main motivations of the Ausubel, Cramton, Milgrom (2006) Clock-Proxy auction is to

protect against the very low revenues which sometimes arise from charging

opportunity costs as in a Vickrey Auction (zero revenue in the example). In

the above example, the procedure is successful in this regard since the base

prices exceed opportunity costs by a significant amount.

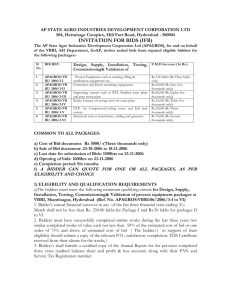

Figure 3 presents the 10-40 GHz auction outcome. Columns 4-10 detail

the assignments of the Lots, column 11 the amount bid for these assignments

by the 10 bidders. Column 12 details the opportunity cost (Vickrey prices)

and column 13 the base prices payable by these bidders. We have added

to the output of the WDP software a final column which simply details the

starting or reserve prices for the lots. There are two striking feature of this

data. First, the bid amounts considerably exceed both the opportunity cost

and base prices. Second, the base price for each package is either equal to

the opportunity cost or it is equal to the reserve price. This means that,

in the event, given the bids4 , as far as revenue is concerned the modified

4

Note however that bidders might have had incentives to behave differently if Vickrey

3

TieID bidderID bidderName units_1 units_2 units_3 units_4 units_5 units_6 units_7 bidAmount oppCost basePrice ReservePrice

2

1 Arqiva

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

1599000 260500

260500

120000

2

2 BT

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

1001000 179000

179000

60000

2

3 Digiweb

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

142000

39000

39000

20000

2

4 Faultbasic

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

750000

0

30000

30000

2

5 MLL

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

250000 179000

179000

90000

2

6 Orange

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

2999999 261000

261000

120000

2

7 RedM

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

34000

1000

10000

10000

2

8 TMobile

8

0

0

0

0

2

1

8500000 319000

319000

230000

2

9 Transfinite

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

97000

0

20000

20000

2

10 UKBB

0

0

0

0

0

0

4

420000

0

120000

120000

Figure 3: Primary Stage Assignment and Base Prices. Note specifically

BP = max{OC, RP }.

second price rule achieved only what Vickrey pricing would have achieved.

Figure 3 details only the outcome of the primary stage of the 10-40

GHz auction. When more than one winning bidders demand the lots in a

band, a new round of assignment stage bid is required to decide the final

lot assignment. It is also a sealed-bid auction and allocations and prices

are again determined on a modified Vickrey basis using the WDP software.

The logic of this relies on the within band differences of valuations being

of second order importance compared to between band differences. In the

event, this was borne out by the bidding behaviour.

The main conclusions of this paper are as follows. The clock phase of

the auction appears to have had a marked impact on the subset of valuations which were effectively reported by bidders throughout the primary bid

phase. This is consistent with what the auction format is designed to achieve:

bidders receive information during the clock stage which enables them to focus their attention on plausible outcomes and this reduces the combinatoric

complexity of the task of reporting "valuations" via bids. This focussing lead

to a successful outcome in the sense that the format elicited consistent bids

which lead to the allocation of all the spectrum. With some reservations5

the allocation was probably reasonably efficient consistent with the stated

objectives of Ofcom. From the point of view of achieving high revenues–

not an objective of Ofcom, but of interest for other potential adopters of the

format, the auction appears to have generated rather low prices. Inspection

of the data shows that bidders focussed heavily on the assignments thrown

up by the clock phase and this lead to low opportunity costs given reported

preferences (low Vickrey prices). The situation was exacerbated by many

pricing had been adopted. See for example Day and Milgrom’s (2007) discussion of bidder

shills.

5

Briefly detailed in section 4.4.

4

bidders making a large number of "redundant" bids leading to there being

far fewer "effective" bids than the number of actual bids made during the

auction. Due to the sparsity of effective bids, the modified second price rule

simply did not have any leverage to protect revenue as discussed above and

displayed in figure 3.

2

The Primary Bid Stage

2.1

Spectrum Packaging and Combinatorics

Spectrum Packaging The process was for spectrum at 10-40 GHz. One

of the design features of the auction was to group the ten 10 GHz sublots,

the two National 28GHz sublots and the six sublots each of National 32

GHz and National 40 GHz. This grouping reduces the number of packages

on which bidders have to deal with in the primary stage of the auction at

the cost of having an extra (assignment stage) stage, see Figure 4.

Number of

lots

Spectrum

Eligibility Points per

lot

Lots 1 - National 10 GHz

10

1

Lots 2 - National 28 GHz

2

6

Lots 3 - First Sub-National 28 GHz

1

2

Lots 4 - Second Sub-National 28 GHz

1

1

Lots 5 - Third Sub-National 28 GHz

1

3

Lots 6 - National 32 GHz

6

6

Lots 7 - National 40 GHz

6

3

Figure 4: The Grouping within Lots and associated Eligibility Points.

Notwithstanding the grouping of sublots, there are potentially a large

number of distinct packages for bidders to consider in the primary bid stage.

Specifically, a bidder with the full amount of eligibility points can choose to

bid on 12, 935 distinct non-null packages6 . This is a large but a distinctly

computable number and is certainly much less than the over 134 million

packages which would have resulted without grouping.

6

This number does not take account of the eligibility cap for all bidders of 42 eligibility

points

5

Eligibility points The purpose of assigning eligibility points for each lot

is to determine the terms of trade with which bidders are allowed to transfer

demand from one package of lots to another during the clock phase and for

subsequent supplementary bids. Bidders lose eligibility7 if they fail to bid

and the loss of eligibility restricts their available choices both within the

clock phase and the supplementary bid phase. This gives bidders incentives

to bid actively during the clock phase. The various lots were assigned eligibility points as detailed in Figure 4. One hopes that the eligibility points

will correspond to some intrinsic value of the lots which is expected to be

reflected in the valuations of bidders. Of course this is a guess at market

valuations which can impact on the efficiency of the auction. There are

other alternatives,8 but the one adopted has the advantage of simplicity. In

the event the final clock prices were (in £000) 69, 707, 97, 37, 130, 594,

151. This series is strongly positively correlated with the eligibility points

per lot 1, 6, 2, 1, 3, 6, 3, having a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.96.

Although this high correlation certainly does not establish the correctness

of the choice of eligibility points, neither does it provide evidence against.

Bidder

Initial Eligibility

Arqiva

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

TMobile

Transfinite

UKBB

24

42

7

9

25

18

2

26

12

42

End ClockPhase

Eligibility

13

15

2

6

0

18

0

23

2

3

E: Eligibility of BP: Base Price BP/E

Acquired Lots

(£000's)

12

6

2

3

9

12

1

23

2

12

260.5

179

39

30

179

261

10

319

20

120

21.7

29.8

19.5

10

19.9

21.7

10

13.9

10

10

Figure 5: Base Prices per aquired Eligibility Points by Bidder

Since all bidders began with a legislated maximum of not more than 42

eligibly points, the number of possible bids is much reduced–there are only

7

Specifically, during the clock phase bidders cannot ’spend’ more eligibility than they

spent in the past. During the supplementary bid phase bidders can bid unrestricted

amounts (i.e. no limit on maximum) for lots within their end of clock phase eligibility but

are restricted in how much they can bid on packages which exceed this eligibility.

8

For instance, and specifically, Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2006) propose a ‘revealed preference’ activity rule.

6

6, 928 possible packages. In practice, most bidders began with fewer than

the maximum eligibility points, RedM with only two initial eligibility points

has only five feasible packages. Evidently, given these numbers, it is not

completely beyond the bounds of reason that bidders might enter bids for

each distinct package within their entitlement constraint.

Post clock phase combinatorics At the termination of the clock phase,

the number of eligibility points remaining for the bidders will typically be

reduced and in the 10-40 GHz auction the eligibility of all bidders was indeed

reduced for all bidders except one (Orange). UKBB started with 42 but

ended with only 3; T-Mobile started with 26 and ended with 23. Column

4 of Figure 6 gives details for all bidders. Column 5 of Figure 6 illustrates

that for many bidders the scale of the problem of detailing within eligibility

bids, was perhaps not impossibly large.

Bidder

Initial

Eligibility

Initial number of

possible packages

End clock-phase Number of withinEligibility

eligibility post clock

packages

Arqiva

24

1885

13

334

BT

42

6928

15

499

Digiweb

7

65

2

5

Faultbasic

9

123

6

45

MLL

25

2108

0

0

Orange

18

840

18

840

RedM

2

5

0

0

TMobile

26

2329

23

1672

Transfinite

12

267

2

5

UKBB

42

6928

3

267

Figure 6: Eligibility combinatorics: The number of potential packages on

which bidders may wish to bid: initial and within eligiblity post-clock phase.

Figure 7 displays the actual numbers of bids made by each bidder both

in the clock phase and in the supplementary bid phase of the principal stage

of the auction. Figure 7 also decomposes the supplementary bids into those

which exceeded the terminal eligibility following the clock phase (for which

prices were bounded by clock prices) and those within this eligibility for

which the prices were not so bounded. At the supplementary bid stage the

auction rules distinguish between bids which exceed the bidders terminal

eligibility and those which do not. Bidders are allowed to post unrestricted

bids for packages within their terminal eligibility but are constrained by the

ruling clock prices (when the bidder had sufficient eligibility) for bids on

7

packages which exceed their terminal eligibility. This means that if prices

have risen during the clock phase, there may be little purpose in making lots

of ineffectual bids for initial rather than final eligibility. The clock phase

therefore reduces the size of the combinatoric valuation problem and provides some price information which may be useful in further focussing bids.

The potential importance of the within eligibility distinction is illustrated

by T-Mobile’s bidding: for supplementary bid packages exceeding terminal

eligibility, the average bid was £737, 500, for supplementary bid packages

not exceeding terminal eligibility the average bid was £6, 894, 470.

clock

sealed

sealed exceeding

terminal eligibility

sealed not

exceeding terminal

eligibility

Arqiva

17

22

0

22

BT

17

544

425

119

Digiweb

17

1

0

1

Faultbasic

17

12

6

6

MLL

9

15

9

6

Orange

17

4

0

4

Bidder\Bi

ds

RedM

9

2

1

1

TMobile

17

106

14

92

Transfinite

17

1

0

1

UKBB

17

3

2

1

Figure 7: The number of actual bids by bidder and type of bid

2.2

Redundant and Effective Bids

A very noticeable feature of the bidding is that some bidders made a large

number of redundant (or more accurately almost redundant) bids so that

the effective registration of reported values was much less than the number

of bids entered. We will illustrate with the following selection of the last

few supplementary bids from one of the bidders (BT). Figure 8 displays

the bid amount as the second column and the package bid for in the seven

subsequent columns. Note that the amount of the bid in the first row is at

least as large as any subsequent bid but the package corresponding to this

bid is a subset of all but two of the other packages bid for. Essentially,9 this

9

It is important to note that under the rules of the auction, bids which are "redundant"

in this sense can impact on the outcome of the auction. Both the assignment and revenue

can be changed. The reason is to do with the tie breaking rules of the auction. For

8

means that BT signals to the auction, for example, that it is as content with

one unit of lot 6 as it is with 6 units of lot 6 plus 2 of lot 7 (the last bid).

Hence, the only effective bids in figure 8 are the three highlighted in italics.

Proceeding in a similar way with the whole set of bids, many other bids can

be deleted–including some clock bids.

Bid

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

1001000

1001000

1000500

1000500

1001000

1001000

1001000

1001000

1001000

1001000

1001000

1001000

1001000

Lot 1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Lot 2

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Lot 3

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Lot 4

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Lot 5

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Lot 6

1

1

0

0

1

1

1

2

2

2

4

5

6

Lot 7

0

2

1

2

3

4

5

3

4

6

2

2

2

Figure 8: Illustration of redundant bids

Many bidders had such redundant bids which markedly reduced the number of effective bids below the number of actual bids detailed in figure 7.

Figure 9 details this effective bid deficit. One sees that the case of BT is

particularly marked–out of 561 bids only 2 were effective in the sense we are

using the word. As bidders added supplementary bids, sometimes the effective number of bids were therefore reduced–bids were made redundant by

subsequent supplementary bids. More bidding generally meant less effective

bids.

This marked ‘reduction’ in the quantity of effective bids may well have

had significant consequences for the outcome of the auction, we discuss this

via some counterfactual alternatives in section 2.3.

The effective bid data are sufficiently reduced that we can get a good

grasp of the mechanisms behind the outcome by listing the effective bids

for the majority of the bidders for whom the number of effective bids were

single digits. Figure 10 displays the list of effective bids made by these 8

bidders. In total there are only 31 bids in contrast to the 700 or so by these

bidders in the actual auction. The highest bids for each of the 8 bidders are

highlighted in italics, for MLL there are two equally high bids (but select the

assignments with equal value of bids, the auction prefers to select the one that assigns

most spectrum (for which the starting prices are charged). Sections 2.3.1 and 2.4 discuss

further.

9

Bidder

Arqiva

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

TMobile

Transfinite

UKBB

clock bids sealed bids

17

17

17

17

9

17

9

17

17

17

22

544

1

12

15

4

2

106

1

3

total

effective sealed

effective

bids

bids

22

22

2

2

1

3

1

2

6

6

3

3

2

2

106

106

0

3

3

7

Figure 9: The Effective Bid deficit: numbers of actual and effective bids for

each seller.

bid for unit of lot 2 at £250, 000). Suppose each bidder were assigned the

package on which it bid highest, this is a feasible assignment since there is

a nonnegative excess supply for each Lot. This assignment, at zero price is

in the core and it is evidently also bidder optimal. Hence, the auction rules

applied only to this subset of bidders establishes a zero price–or rather, the

bidders are required to pay the starting (reserve) prices for the individual

lots they receive. This conclusion is confirmed by running the auction WDP

software for the data in figure 10, the results are displayed as figure 11.

In the next section (section 2.3) we also carry out this calculation on the

original bid data but with all the bids of Arqiva and T-Mobile deleted, the

calculations give different results because of the treatment of lots which are

in excess supply. The main point is that bidders listed in figure 10 ended

up expressing rather little demand.

2.3

Discussion of Counterfactual Outcomes

The total number of eligibility points required to purchase all lots is 82

which, at reserve of £10K per eligibility point, would cost £820,000. In the

event, the auction raised a revenue of £1,434,630, i.e. somewhat less than

twice the reserve price. In this section we explore the effect on revenues of

a number of counterfactual bidding scenarios.

10

Lot 1

BT

BT

Digiweb

Digiweb

Digiweb

FaultBasic

FaultBasic

MLL

MLL

MLL

MLL

MLL

MLL

Orange

Orange

Orange

RedM

RedM

RedM

RedM

RedM

Transfinite

Transfinite

Transfinite

UKBB

UKBB

UKBB

UKBB

UKBB

UKBB

UKBB

Total Demand

Supply

XS Supply

Lot 2

0

0

4

3

2

0

0

0

2

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

4

10

6

Lot 3

1

0

0

0

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

2

1

Lot 4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

Lot 5

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

Lot 6

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

0

Lot 7

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

2

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

1

6

6

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

2

2

4

3

1

2

1

2

6

4

Bid

1,000,500

1,001,000

200,000

198,000

142,000

535,000

750,000

250,000

50,000

250,000

60,000

110,000

34,000

2,999,999

1,492,957

2,857,887

29,000

34,000

179,000

79,000

97,000

179000

79000

97000

394,000

599,000

420,000

378,000

170,001

302,000

500,001

Figure 10: Complete list of effective bids for bidders other than Arquiva

and TMobile. Note that supply exceeds the value maximising assignment

for these bidders.

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage run on the data in Figure 10.

TieID

bidderID bidderNa units_1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

BT

Digiweb

FaultBasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

Transfinite

UKBB

0

4

0

0

0

0

0

0

units_2

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

units_3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

units_4

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

units_5

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

units_6

1

0

0

0

2

1

1

1

units_7

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

2

bidAmou oppCost

1001000

200000

750000

250000

2999999

179000

179000

599000

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

basePrice

60000

40000

30000

60000

120000

60000

60000

120000

550000

Figure 11: Calculation of Assignment and Base Prices from data of Figure

10.

11

2.3.1

Impact of deleting two bidders (Arqiva and T-Mobile).

We saw in section 2.2 that many of the bidders had made rather few effective

bids, notwithstanding the much larger number of actual bids made. Here we

evaluate via the auction WDP software the result of the primary bid stage

in the counterfactual situation in which only the bidders listed in figure 10

were present (and in which they made the same bids).

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage (with Arqiva and T-Mobile not present)

TieID bidderID bidderName units_1 units_2 units_3 units_4 units_5 units_6 units_7 bidAmount oppCost basePrice

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

10

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

Transfinite

UKBB

4

4

0

2

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

3

0

1

1

2

0

0

1

0

0

0

2

1001000

200000

750000

250000

2999999

34000

179000

599000

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

240000

40000

30000

110000

180000

10000

60000

120000

790000

Figure 12: Ofcom software calculation of Primary Stage Assignement and

Base Prices resulting from the deleting 2 bidders (Arquiva and TMobile).

The sparsity of bidding leads to low prices.

Comparing figure 12 with figure 11, there are some discrepancies. Looking at figure 12, we see that MLL is allocated 2 units of Lot 1, 1 unit of Lot

2 and 1 unit of Lot 7 for which MLL bid £250,000, whereas in figure 10 MLL

has no such effective bid. The reason is that because of MLL’s effective bid

of £250,000 for a single unit of Lot 2 we have eliminated, in constructing

figure 10, the bid which determines MLL’s assignment in the figure 12. Essentially, the reason is that there is excess demand for the other lots and

the auction mechanism has a revenue tie-breaking rule which chooses to allocate this spectrum at the starting prices. This illustrates what we pointed

out in section 2.2, that our usage of language in defining "redundant bids"

and "effective bids" is something of an oversimplification. Nevertheless the

language remains useful in analysing the auction outcome.

2.3.2

"Pay as bid" Clock stage

Another counterfactual of interest is what would have happened if the auction had terminated after the clock phase but now with bidders paying their

terminal bids. If bidders did not change their behaviour then the revenue

would have been substantially higher - over £6.7m. Under these counterfactual conditions, the actual auction earned less than a quarter of the (counterfactual) "pay as bid" clock auction.

12

Of course, bidders may well have had incentives to bid very differently.

In particular, the incentive to halt price increases through demand reduction

may have been more acute. Given the feature that bidders cannot, in the

supplementary bid phase, expand their demand at higher prices than those

pertaining in the clock phase10 , there seems no strong reason for this to be

the case. It is difficult to think that bidders believed that they had marked

incentives to bid above their valuations in the clock auction so it does seem

that the revenue only managed to capture a small share of this value11 .

2.3.3

Pseudo Clock Auction: Impact of deleting all supplementary bids

If one takes the view that some of the supplementary bids may have been illconsidered and resulting in a sparsity of effective bids, a natural comparison

involves deleting some of the bids from the supplementary bid stage of the

auction. The second table in Figure 13 provides a natural comparison–what

would have happened if the auction had been terminated after the clock stage

but otherwise under the same rules. If bidders did not change their behaviour

then we see, the revenue increases from approximately £1.4m to £2.7m i.e.

under these conditions revenue would have nearly doubled. The big question

is whether bidders would be likely to change their behaviour. In our view,

there is no strong evidence that behaviour during the clock phase would

have been much different. Unless the supplementary bids are deliberately

misleading12 many have the appearance of something of an afterthought.

Some bidders may have expected the auction to be more or less over after

the clock stage. Second, as we will discuss later, most bidders tended to bid

for their putative clock allocations in the supplementary bid phase.

2.3.4

Impact of deleting BT’s supplementary bids only.

We have seen that although BT made the most bids, only 2 were effective.

The supplementary bids cancelled out the clock bids to the possible detriment to auction revenues. Suppose we delete all the supplementary bids

from BT, in this case the software shows that the assignment is impacted

10

Ausubel Cramton and Milgrom (2006) proposed a relaxed (revealed preference) activity rule in contrast to the unrelaxed activity rule of this auction.

11

It is worth noting in this respect that Ofcom’s stated objectives are efficiency rather

than revenue. However, Ausubel, Cramton Milgrom (2005) emphasise both revenue and

efficiency considerations.

12

Since the data are public, bidders might wish to confuse Ofcom, business rivals and

potential competitors in future auctions with similar formats.

13

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage

bidderName

units_1

units_2

units_3

units_4

units_5

units_6

units_7

Arqiva

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

TMobile

Transfinite

UKBB

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

2

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

4

bidAmount oppCost basePrice

1,599,000

1,001,000

142,000

750,000

250,000

2,999,999

34,000

8,500,000

97,000

420,000

260,500

179,000

39,000

0

179,000

261,000

1,000

319,000

0

0

260,500

179,000

39,000

30,000

179,000

261,000

10,000

319,000

20,000

120,000

1,417,500

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage (Clock Bids Only Evaluated)

bidderName

units_1

units_2

units_3

units_4

units_5

units_6

units_7

Arqiva

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

TMobile

Transfinite

UKBB

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

3

0

2

0

0

0

3

0

1

0

0

0

1

0

1

bidAmount oppCost basePrice

1,451,000

918,000

138,000

281,000

0

1,782,000

0

1,891,000

97,000

151,000

747,000

454,000

0

205,000

0

604,000

0

616,000

24,000

6,000

747,000

454,000

20,000

205,000

0

604,000

0

616,000

24,000

30,000

2,700,000

Figure 13: The Primary Bid Stage Outcome compared with the counterfactual calculation on the Clock Phase data only.

mainly by BT now registering a positive value for units of Lot 7 with the

result that BT gains 2 units of 40 GHz at the expense of UKBB. BT pays

and extra £11, 000 for these two lots. UKBB receives one unit of Lot 6 as

a by-product at the expense of MLL. As a result, MLL pays £149, 000 less

than before but all other bidders pay more. The impact on final revenue is

an increase of £86, 500.

2.3.5

Impact of deleting Arqiva’s supplementary bids only.

Arqiva’s supplementary bids were all effective ones, but figure 15 shows that

they had rather little impact on the auction outcome. Arqiva itself would

have won more spectrum (Lot 4) at a cost of £23K. Taking Arqiva’s supplementary bids at face value this additional unit of spectrum was revealed

to be not worth the cost. The auction revenue is about £7K higher.

2.3.6

Impact of deleting T-Mobile’s supplementary bids only.

After BT, T-Mobile exercised the largest number of supplementary bids.

In contrast to BT, but as with Arqiva, (most of) T-Mobile’s supplementary

bids were "effective" in the sense used above–they did not cancel each other

out. It is interesting to note that if T-Mobile’s supplementary bids alone

14

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage (with BT’s Supplementary Bids Deleted)

TieID bidderID bidderName units_1 units_2 units_3 units_4 units_5 units_6 units_7 bidAmount oppCost basePrice

1

1 Arqiva

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

1599000 212000

267000

1

2 BT

0

0

0

0

0

1

2

896000 190000

190000

1

3 Digiweb

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

142000

50000

50000

1

4 Faultbasic

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

750000

0

55000

1

5 MLL

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

60000

22000

30000

1

6 Orange

0

0

0

0

0

2

0

2999999 294000

294000

1

7 RedM

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

34000

1000

34000

1

8 TMobile

8

0

0

0

0

2

1

8500000 352000

352000

1

9 Transfinite

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

97000

0

20000

1

10 UKBB

0

0

0

0

0

1

2

599000 212000

212000

1504000

Figure 14: The Primary Bid Stage Outcome with the Supplementary Bids

of BT deleted.

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage (with Arqiva's Supplementary Bids Deleted)

TieID

bidderID bidderNa units_1

units_2

units_3

units_4

units_5

units_6

units_7

bidAmou oppCost basePrice

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

2

0

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

1

4

1451000

1001000

142000

750000

250000

2999999

29000

8500000

79000

420000

Arqiva

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

TMobile

Transfinite

UKBB

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

283500

179000

39000

0

179000

279000

18000

337000

0

0

283500

179000

39000

30000

179000

279000

20000

337000

30000

120000

1496500

Figure 15: The Primary Bid Stage Outcome with the Supplementary Bids

of Arqiva deleted.

15

Outcome of the Primary Bid Stage (with T-Mobile's Supplementary Bids deleted)

bidderName

Arqiva

BT

Digiweb

Faultbasic

MLL

Orange

RedM

TMobile

Transfinite

UKBB

units_1

0

0

2

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

units_2

2

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

units_3

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

units_4

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

units_5

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

units_6

0

1

0

0

1

2

0

2

0

0

units_7

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

1

0

4

bidAmount oppCost basePrice

1,599,000

1,001,000

142,000

750,000

250,000

2,999,999

34,000

1,891,000

97,000

420,000

260,500

179,000

39,000

0

179,000

261,000

1,000

319,000

0

0

260,500

179,000

39,000

30,000

179,000

261,000

10,000

319,000

20,000

120,000

1,417,500

Figure 16: The Primary Bid Stage Outcome with the Supplementary Bids

of T-Mobile deleted.

are deleted and the primary bid stage outcome recalculated, one finds that

the outcome is unaffected. In other words, even though T-Mobile made a

large number of effective supplementary bids, none of them impacted on the

outcome of the auction. The reason for this rests largely with the sparsity

of effective bids from other bidders.

2.4

Starting versus Reserve Prices: A Strange Feature

We return to the discussion of assignment and pricing when supply exceeds

demand for a particular lot. It seems the following situation can arise.

Bidder 1 bids £1m for a 42 eligibility point package and also bids £1m for a

small subset of that package, say Lot 3. According to our definition of section

2.2, only the second bid is effective. All other bidders only bid on packages

which include Lot 3 in the first round of the clock auction and then bid

for zero lots in the second round, no other bidders enter any supplementary

bids. Hence, since Bidder 1’s bids are revenue maximising and inconsistent

with all other bids, Bidder 1 wins. The auction WDP software assigns 42

eligibility points to Bidder 1–even though according to Bidder 1’s bids, 41

of those eligibility points have no value. The rest of the spectrum is retained

by Ofcom even though the other bidders did bid for the other spectrum (in

combination with Lot 3).

Note that Bidder 1 will not pay the zero opportunity cost, or £10K for

item 3, but £420K for the 42 eligibility points worth of spectrum assigned.

Evidently, Bidder 1 would rather pay £10K for the lesser package according

to the values expressed by his or her bids. Hence, the outcome is not a

bidder optimal core allocation.

An alternative would be to treat the starting prices, i.e. reserve prices

as bids in determining the assignment.

16

3

The Assignment Stage

After the primary stage bid round, when there are more than one winning

bidders demanding the lots in a band, a new round of assignment stage bid is

required to determine the final allocation of lots. Like the supplementary bid

round, the assignment bid round is a sealed-bid auction. Relevant bidders

submit their bids to Ofcom, and the winning bids are those compatible

bids with the largest amount bid. The prices payable by the bidders in

the assignment stage are called Top-Up prices, which are core prices that

generate a bidder-Pareto optimal allocation (Cramton, et al. 2006, Chapter

3 and 5; Day and Raghavan, 2007).

Although the grouping of lots in the primary bid phase reduces the

number of packages for that stage, it potentially does so at the cost of

introducing other complications. For the philosophy behind the grouping

and sequential auction design to be valid, it is important that the tail does

not wag the dog. It is predicated on the assumption that the within group

assignments are of second order importance to the first stage.

3.1

Bidding

The striking aspect of the bids is that Orange appears to have had strong

views on which lots it received and bid significantly higher (£105K) for its

preferred assignment than any other bids. This bid was significantly less

than Orange’s primary stage bid for the two lots of this spectrum which it

was assigned (approximately £3m). The relative magnitudes of these bids

appears to corroborate the view that the within Lot assignment was indeed

of second order importance.

17

Bidder

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

BT

MLL

MLL

MLL

MLL

MLL

MLL

Orange

Orange

Orange

Orange

Orange

TMobile

TMobile

TMobile

TMobile

TMobile

32GHz Nat band

Frequecy Assignment

Stage Bid

option

Lot 1

0

Lot 2

10000

Lot 3

5000

Lot 4

4000

Lot 5

9000

Lot 6

0

Lot 1

0

Lot 2

3000

Lot 3

5000

Lot 4

5000

Lot 5

3000

Lot 6

0

Lots 1 and 2

105000

Lots 2 and 3

15000

Lots 3 and 4

0

Lots 4 and 5

15000

Lots 5 and 6

15000

Lots 1 and 2

20229

Lots 2 and 3

15151

Lots 3 and 4

10099

Lots 4 and 5

5048

Lots 5 and 6

0

Assignment stage bids for 32 GHz lots.

4

4.1

Evaluation and Conclusions

The auction mechanics and correspondence with the documentation

The auction mechanics seemed to work reasonably smoothly–although we

have not shared in bidder feedback.

4.2

Bidder behaviour

Some bidders appear not to have been prepared. Some of the documentation

may have been obscure. We did not make a systematic search of documentation available to bidders prior to the auction, but found the translation of

essentially mathematical concepts from legal phraseology a challenge.

A recommendation for any future auctions using similar formats is to

invest heavily in helping bidders via a multiplicity of software promptings

and other tools. For instance, we would recommend a device which pointed

18

out to bidders when they bid more for a subset of lots than a superset–or

made them choose ‘more consistent’ different bids.

The suspicion of lack of bidder preparedness makes it hard to gauge the

potential of the format in situations where bidders have spent more resources

in preparing. However, the reservations detailed below about low revenues

might remain a feature even with well-prepared bidders.

4.3

Revenue

The auction seems very likely to have produced low revenue. One wonders

to what extent low revenue is a natural outcome for such auctions. If we

paraphrase the theory behind the auction format, insofar as it can be taken

from13 Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2006). There are two problems14

with Vickrey auctions which the Clock Proxy design is intended to overcome.

1. Combinatoric complexity For even moderate numbers of objects, there

are too many potential combinations of objects on which to make bids.

2. Vickrey outcomes are not necessarily ‘competitive’. Specifically,

outcomes are not in the core when the auctioneer is included as an

agent with preferences increasing in auction revenues. This means

that Vickrey outcomes can yield very low revenues.

The Ausubel, Cramton and Milgrom (2006) Clock Proxy auction and

the UK 2008 10-40GHz Spectrum auction deals with these problems by two

separate devices.

The first is that rather than simply ask bidders to produce an unfeasibly

long list of sealed bid valuations for packages, there is a preceding clock

phase to the auction. The progress of prices and bids during the clock phase

gives guidance to the bidders so that they are better able to gauge which

packages are likely to be of interest to them. In short, the clock phase is

designed to reduce the number of bids and to focus only on relevant ones.

The second is that rather than calculate prices according to the Vickrey

opportunity cost formula, this is modified to guarantee that the assignment

is in the core. Of all core assignments, the bidder optimal one is chosen. This

is supposed to guarantee ‘reasonable’ revenues given reported valuations.

So, the clock phase should help bidders to report most of the valuations

which are likely to be relevant and the Vickrey pricing modification should

13

14

See also, e.g. Day and Milgrom (2007).

Note however that Ofcom’s stated aim is to maximise efficiency rather than revenue.

19

help stop the revenues becoming too low (at some potentially troublesome

constellations of preferences).

There is a real sense in which these two objectives are in conflict. Helping bidders reduce the number of bids they need to make in addition to the

bids corresponding to the eventual assignment reduces the reported opportunity cost of that assignment. The problem–for revenue–arises when the

clock phase does its job too well and bidders jump from the end of the clock

phase to immediately reporting high valuations for packages which together

constitute a feasible assignment. This kills the opportunity cost of the assignment and notwithstanding the modified Vickrey rule can easily lead to

low revenues.

It is very instructive to compare the final clock bids with the highest

supplementary bids for each of the bidders.

Arqiva Arqiva made its highest supplementary bid, £1, 600K, for the same

package as it made its final clock phase bid on (0, 2, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0). Arqiva

also made a very near bid on a subset of this package, it bid £1, 599K

on the package (0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0) which is the one it was eventually

assigned.

BT BT bid its highest supplementary bid of £1, 001K for the same package as it made its final clock phase bid on (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 2). BT also

bid £1, 001K of hundreds of other packages including (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0)

which it was eventually assigned.

Faultbasic Faultbasic bid £350K in the supplementary round on the package of its final clock phase bid (0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1). Its highest supplementary bid of £750K was for a subset (0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0) of this package.

Faultbasic was eventually assigned this subset.

MLL MLL ended the clock phase with zero eligibility but made its highest

supplementary bid of £250K on its final non null clock bid (0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0).

MLL also bid £250K on 10 other packages, including (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1)

which it was eventually assigned.

Orange Orange made its maximum supplementary bid £2, 999, 999 on its

final clock phase package (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 0) but also bid the same amount

on the subset (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0) which it was eventually assigned.

RedM RedM ended the clock phase with zero eligibility but made its

highest supplementary bid of £34K on its final non null clock bid

(0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0). RedM was eventually assigned this package.

20

T-Mobile T-Mobile made its maximum supplementary bid of £8.5m on

the same package as its final clock phase bid. T-Mobile was eventually

assigned this package.

Transfinite Transfinite only made one supplementary bid. This bid was

on the same package as its final clock phase bid and was in the same

amount–evidently a redundant bid.

UKBB UK Broadband terminated the clock phase with a bid of £151, 000

for the package (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1) but made its highest supplementary

bid of £500, 001 for the package (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1). Eventually, UK

Broadband was assigned the package (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 4) on which it had

made the bid £420, 000 during the clock phase15 .

To summarise, all but one of the bidders made their highest supplementary bid either on their final clock phase package, or on a subset of it. In

behaving in this way, bidders are clearly using the clock phase of the auction

to focus their attention on a selection of packages in a way consistent with

the philosophy of the auction design. Arguably, however, from the point of

view of revenue, bidders have ‘gone too far’ in this respect. It seems likely

that this bidding behaviour has lead to lower revenues than might have obtained, for example, in an ascending clock auction with pay as bid pricing.

In the auction this bidding behaviour was a feature both for bidders who

had a large proportion of effective bids (e.g. T-Mobile) and for those which

had a low proportion. In other words, the marked reduction in the number of effective bids displayed in figure 9 is likely to have exacerbated any

‘shortfall’ in revenue, but may not have been its root cause.

4.4

Efficiency

UK Spectrum awards are not designed to achieve maximum revenues, so the

low-revenue feature highlighted above is not necessarily a major issue in this

context.

The assignment seems to have been more stable than the prices in the

sense that the assignment appears to vary less in the various counterfactual

situations we have discussed so far. Compared to the putative assignment at

the end of the Clock Phase, the final assignment gives more spectrum to the

three bidders MLL, RedM and UK Broadband. This spectrum came at the

expense of Arqiva, BT and Orange who all bid the same or very nearly the

15

It is worth observing that Lot 7 finished the clock phase in excess supply.

21

same for subsets of their putative Clock Phase packages as proper subsets

of those packages. It is noticeable that the spectrum flows from bidders

who generally expressed high values to those who generally expressed low

values. One possibility is that the small bidders have found niches between

the expressed valuations of the large bidders which would not have been

present under the fuller expression of valuations which would have been

represented by a larger number of effective bids. However, this interpretation

is speculative. One suspects that the auction worked quite well in allowing

bidders who needed certain lots and valued them highly e.g. T-Mobile and

Orange to acquire the appropriate spectrum.

5

References

Ausubel, Lawrence M., Peter Cramton, and Paul Milgrom (2005) “Comments on Experimental Design for Evaluating FCC Spectrum Auction Alternatives”, 1 June, 2005http://wireless.fcc.gov/auctions/isas/Ausubel_et_al.pdf.

Ausubel, Lawrence M., Peter Cramton and Paul Milgrom, 2006, “The

Clock Proxy Auction: A Practicable Combinatorial Auction Design”, in

Cramton, Yoav, Shoham and Steinberg (Eds.), 2006.

Ausubel, Lawrence M., Peter Cramton and Paul Milgrom, 2006b, “The

Clock Proxy Auction: A Practicable Combinatorial Auction Design”, Presentation National Telecommunications and Information Administration Advanced Technology Forum, http://www.ntia.doc.gov/forums/2006/specman/ntia_cramton.pdf.

Cramton, Peter, Yoav, Shoham and Richard, Steinberg, 2006, Combinatorial Auctions, MIT Press.

Day, Robert W. and Paul Milgrom, 2007, “Core-Selecting Package Auctions”, to appear International Journal of Game Theory.

Day, Robert W. and S. Raghavan, 2007, “Fair Payments for Efficient

Allocations in Public Sector Combinatorial Auctions”, Management Science,

53(9), pp. 1389-1406.

Ofcom, The Wireless Telegraphy (Licence Award) (No.2), Regulations

2007.

Telecommunications Authority of Trinidad and Tobago, First Steps toward a Liberalised Telecommunications Sector, http://www.tatt.org.tt/auction.htm.

22