ACCT322, 9d, Inventory

advertisement

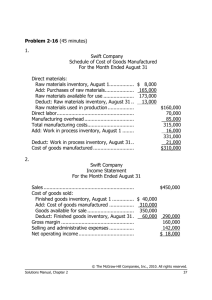

ACCT322, 9d, Inventory Readings Answer the questions below: 1. See the article below entitled “Ghost Goods: How to Spot Phantom Inventory.” (A) Inventory valuation involves which two elements? (B) Why is inventory an attractive target for fraud? (C) What mistakes can auditors make in the observation of a physical inventory count? (D) What specific things did Monus do that were fraudulent? (E) How was Monus caught? 2. See the article below entitled “Crazy Eddie.” (A) Why did Eddie Antar perpetuate this fraud? (B) How did Antar and his subordinates overstate inventory? (C) What happened to Eddie Antar? 3. See the short article below entitled “The Great Salad Oil Swindle.” (A) What steps did Tino De Angelis, CEO of American Salad Oil Company, take to over-state inventory? (B) Do you think De Angelis would have been better off to focus all of his elaborate energy on running a quality company? 4. See the article below entitled “Inventory Chicanery Tempts More Firms, Fools More Auditors” (A) True or False: According to the article, inventory fraud is the easiest way to produce instant profits and dress up the balance sheet. (B) What specific things did Laribee do to overstate its inventory? (C) What was the standing joke among Laribee employees about their auditors? (D) The articles states that companies “can get auditors to swallow all kinds of ruses.” Summarize the two examples given. (E) Could the Phar-mor fraud have been avoided if the auditors had done surprise test counts of inventory? Explain. Ghost Goods: How to Spot Phantom Inventory BY JOSEPH T. WELLS ust a hint of inventory fraud can be a frightening experience for an auditor of financial statements. Indeed, the list of freakish inventory manipulations companies have committed over the last 50 years reads like a rogue’s gallery: McKesson and Robbins, the Salad Oil Swindle, Equity Funding, ZZZZ Best, Phar-Mor. The tried-and-true schemes these and other companies pulled have always given auditors nightmares. A CPA who recognizes how these fraudulent manipulations work will be in a much better position to identify them. FRAUDULENT ASSET VALUATIONS Companies use five techniques to illegally boost assets and profits: fictitious revenues (see “So That’s Why They Call It a Pyramid Scheme,” JofA Oct.00, page 91), fraudulent timing differences, concealed liabilities and expenses (see “Follow Fraud to the Likely Perp,” JofA, Mar.01, page 91), fraudulent disclosures and fraudulent asset valuations. In a 1999 study, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission found misstated asset valuations accounted for nearly half the cases of fraudulent financial statements. Inventory overstatements made up the majority of asset valuation frauds and are the focus of this article. The valuation of inventory involves two separate elements: quantity and price. Determining the quantity of inventory on hand is often difficult. Goods are constantly being bought and sold, transferred among locations and added during a manufacturing process. Figuring the unit cost of inventory can be problematic, too; Fifo, Lifo, average cost and other valuation methods can routinely make a material difference in what the final inventory is worth. As a result, the complex inventory account is an attractive target for fraud. Dishonest organizations usually use a combination of several methods to commit inventory fraud: fictitious inventory, manipulation of inventory counts, nonrecording of purchases and fraudulent inventory capitalization. All these elaborate schemes have the same goal of illegally boosting inventory values. FICTITIOUS INVENTORY The obvious way to increase inventory asset value is to create various records for items that do not exist: unsupported journal entries, inflated inventory count sheets, bogus shipping and receiving reports and fake purchase orders. Since it can be difficult for the auditor to spot such phony documents, he or she normally uses other means to substantiate the existence and value of inventory. Observation of physical inventory. The most reliable way to validate inventory quantity is to count it in its entirety. Even when this is done, little mistakes can allow inventory fraud to go undetected: Management representatives follow the auditor and record the test counts. Thereafter, the client can add phony inventory to the items not tested. This will falsely increase the total inventory values. Auditors announce when and where they will conduct their test counts. For companies with multiple inventory locations, this advance warning permits management to conceal shortages at locations which auditors will not visit. Sometimes auditors do not take the extra step of examining packed boxes. To inflate inventory, management stacks empty boxes in the warehouse. Analytical procedures. Ghost goods throw a company’s books out of kilter. Compared with previous periods, the cost of sales will be too low; inventory and profits will be too high. There will be other signs, too. When analyzing a company’s financial statements over time, the auditor should look for the following trends: Inventory increasing faster than sales. Decreasing inventory turnover. Shipping costs decreasing as a percentage of inventory. Inventory rising faster than total assets move up. Falling cost of sales as a percentage of sales. Cost of goods sold on the books not agreeing with tax returns. MANIPULATION OF INVENTORY COUNTS The auditor relies heavily on observing the client’s inventory. Therefore, it’s quite important for the auditor to take and document test counts. Regrettably, some cases of inventory fraud occur when the client alters the auditor’s working papers after hours (see JofA, Oct.00, page 94). Auditors must maintain adequate security over audit evidence. For instance, say the client receives a large shipment of merchandise five days before the end of the accounting period and picks up all copies of the receiving reports and invoices and secretes them during the audit. Then, during the physical inventory count, employees count the merchandise, which the auditor then tests. Obviously, physical inventory will be overstated by the amount of the unrecorded liability. The client’s advantage with this method is that the amount of the overstatement is buried in the overall cost of sales calculation. An alert auditor can detect these schemes by any one of the analytical methods described above and also can examine the cash disbursements subsequent to the end of the period. If the auditor finds payments made directly to vendors that were not recorded in the purchase journal, he or she should investigate further. Although any inventory item can be improperly capitalized, manufactured goods present a particular problem. Common items capitalized are selling expenses and general and administrative overhead. To detect these problems, auditors should interview manufacturing process personnel to gain an understanding of appropriate charges to inventory. Although there may be many good faith reasons to boost income by capitalizing inventory items, there also may be fraudulent ones. Usually the auditor will find that the CFO, typically at the CEO’s direction, carries out material illegal schemes. Therefore, during normal interviews with key personnel, the auditor always should ask— in a straightforward but nonaccusatory way—if anyone in the company has instructed them to inflate inventory information. There are many ways a dishonest client can attempt to manipulate inventory. An auditor must look at the data with a different mindset, surmising not only how inventory fraud works, but why the client would resort to such improprieties in the first place. The answer is almost always because upper management feels extreme pressure to meet financial projections. The auditor who assesses both motive and opportunity to commit material inventory fraud will end up spotting the ghosts. Perpetrators of Fraud in an Organization Source: “Report to the Nation,” 1996. Institute of Certified Fraud Examiners. See the full report at cfenet.com. ASSESSING THE RISK OF INVENTORY FRAUD Statement on Auditing Standards no. 82, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit, lists many factors at play in cases of financial statement manipulation. In evaluating risks of inventory overstatements, the auditor should answer the following questions. The more “yes” answers, the higher the risk for inventory fraud Is the company attempting to obtain financing secured by inventory? Is inventory a significant balance sheet item? Has the percentage of inventory to total assets increased over time? Has the ratio of cost of sales to total sales decreased over time? Have shipping costs fallen compared with total inventory? Has inventory turnover slowed over time? Have there been significant adjusting entries that have increased the inventory balance? After the close of an accounting period, have material reversing entries been made to the inventory account? Is the company a manufacturer, or does it have a complex system to determine the value of inventory? Is the company involved in technology or another volatile or rapidly changing industry? CASE STUDY: FAR MORE GHOSTS Since he was a kid, Mickey Monus loved all sports—especially basketball. But with limited talents and height (five foot nine on a good day) he would never play on a professional team. Monus did have one trait, however, shared by top athletes: an unquenchable thirst for winning. Monus transferred his boundless energy from the court to the board room. He acquired a single drugstore in Youngstown, Ohio, and within 10 years he had bought 299 more stores and formed the national chain Phar-Mor. Unfortunately, it was all built on ghost goods—undetected inventory overstatements—and phony profits that eventually would be the downfall of Monus and his company, and would cost the company’s Big 5 auditors million of dollars. Here is how it happened. After acquiring the first drugstore, Monus dreamt of building his modest holdings into a large pharmaceutical empire using power buying, that is, offering products at deep discounts. But first he took his one unprofitable, unaudited store and increased the profits with the stroke of a pen by adding phony inventory figures. Armed only with his gift of gab and a set of inflated financials, Monus bilked money from investors, bought eight stores within a year and began the mini-empire that grew to 300 stores. Monus became a financial icon and his organization gained near-cult status in Youngstown. He decided to fulfill a sports fantasy by starting the World Basketball League (WBL) in which no players would be over six feet tall. He pumped $10 million of Phar-Mor’s money into the league. However, the public did not like short basketball players and were not buying tickets. So Monus poured more Phar-Mor money into the WBL. One day, a travel agent who booked flights for league players received a $75,000 check for WBL expenses, but it was disbursed on a Phar-Mor bank account. The employee thought it odd that Phar-Mor would be paying the team’s expenses. Since she was an acquaintance of one of Phar- Mor’s major investors, she showed him the check. Alarmed, the investor began conducting his own investigation into Monus’s illicit activities, and helped expose an intricate financial fraud that caused losses of at least half a billion dollars. THE GAME IS OVER Generating phony profits over an entire decade was no easy feat. Phar-Mor’s CFO said the company was losing serious money because it was selling goods for less than it had paid for them. But Monus argued that through Phar-Mor’s power buying it would get so large that it could sell its way out of trouble. Eventually, the CFO caved in—under extreme pressure from Monus—and for the next several years, he and some of his staff kept two sets of books—the ones they showed the auditors and the ones that reflected the awful truth. They dumped the losses into the “bucket account” and then reallocated the sums to one of the company’s hundreds of stores in the form of increases in inventory costs. They issued fake invoices for merchandise purchases, made phony journal entries to increase inventory and decrease cost of sales, recognized inventory purchases but failed to accrue a liability and over-counted and double-counted merchandise. The finance department was able to conceal the inventory shortages because the auditors observed inventory in only four stores out of 300, and they informed Phar-Mor, months in advance, which stores they would visit. Phar-Mor executives fully stocked the four selected stores but allocated the phony inventory increases to the other 296 stores. Regardless of the accounting tricks, Phar-Mor was heading for collapse. During the last audit, cash was so tight suppliers threatened to cut the company off for nonpayment of bills. The auditors never uncovered the fraud, for which they paid dearly. This failure cost the audit firm over $300 million in civil judgments. The CFO, who did not profit personally, was sentenced to 33 months in prison. Monus went to jail for 5 years. SHARPENED HINDSIGHT Why didn’t the auditors see signs of fraud at Phar-Mor? Perhaps, they just believed in their client—they read the newspaper articles and watched the television spots on the hard-driving Monus and bought the hype. They might have conducted the audit under a faulty assumption: Their client would not be motivated to commit financial statement fraud because it was making money hand over fist. Looking back, the auditors might have been able to spot the ghosts if anyone had asked a fundamental question: How can a company make money by selling goods below cost? JOSEPH T. WELLS, CPA, CFE, is founder and chairman of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Austin, Texas. He can be reached at joe@cfenet.com. Mickey Monus CRAZY EDDIE This is a famous case involving inventory fraud. Crazy Eddie was a consumer electronics chain which was primarily located in the Northeastern United States. It was started in the 1970s in Brooklyn, New York, by businessman Eddie Antar. The chain became well-known for its television and radio commercials in which actor Jerry Carroll delivered his lines rapid-fire, proclaiming in a loud voice that “Crazy Eddie will beat any price you find,” always ending his sales pitch with the memorable tag-line “Crazy Eddie - His Prices Are In-saaane!” The hyperactive TV spokesman became so identified with the company that many viewers assumed that he was the owner of the company, despite the fact that Crazy Eddie was always referred to in the third person. In 1989 the chain suffered a major scandal when Eddie Antar and his family were accused (and eventually convicted) of “cooking the books” in order to skim money and inflate inventory. Antar was found to have sold used electronics as new, committed insurance fraud, faked inventory, and skimmed most of the cash payments to avoid taxes. Having taken the company public (the stock was worth hundreds of millions of dollars at that time), Antar became preoccupied with his company’s stock. Antar realized that he had to keep posting impressive profits to maintain the upward trend in the stock price. Within six months after going public, Antar ordered a subordinate to overstate inventory by $2 million, resulting in the firm’s gross profit to be overstated by the same amount. The following year Antar ordered year-end inventory to be overstated by $9 million. This was achieved by preparing count sheets for inventory that did not exist and by including in inventory consigned merchandize and goods being returned to suppliers. The firm was later purchased in a hostile takeover. The buyers soon found out that some $80 million in reported inventory in fact did not even exist. Meanwhile, Antar had fled to Israel using the name David Cohen, where he lived until 1994 when he was extradited back to the United States. He was subsequently sentenced to eight years in jail, ordered to pay over $150 million in fines and also owes more than a billion dollars from civil suits in the U.S. In 1999, the grandchildren of Eddie, Allen and Mitchell Antar, revived the Crazy Eddie electronics chain with a store in Wayne, New Jersey, and as an online Internet venue. In 2001, they hired a newly-released prisoner named Eddie Antar as manager. However, in 2004 Crazy Eddie went out of business again. We don’t know what grandpa Eddie or his grandsons are doing today. THE GREAT SALAD OIL SWINDLE One of the most famous scams in modern finance occurred in 1960, when Tino De Angelis, CEO of a very large salad oil company, borrowed $200 million that was secured by large tanks of salad oil. But unbeknown to the creditors, the company had significantly overstated its oil inventory using three methods: (1) 40-foot tanks were filled with 37 feet of seawater, which left 3-feet of oil floating on top for all the foolish creditors to admire. (2) Tino listed more tanks on the inventory records than actually existed. Then he had his men quickly repaint the numbers on the tanks after the creditors had examined them, thus causing the foolish creditors to count the same tanks twice. (3) Tino built underground pipes that could rapidly transfer oil from one tank to another, causing the same salad oil to be counted twice by the foolish creditors. In the end, the foolish creditors were left out in the cold looking for their $200 million and Tino was put in the slammer for 7 years. Tino De Angelis stands amid steamy clouds in his New Jersey refinery. Convenient Fiction: Inventory Chicanery Tempts More Firms, Fools More Auditors --- A Quick Way to Pad Profits, It Is Often Revealed Only When Concern Collapses --- A Barrel Full of Sweepings By Lee Berton, Staff Reporter of The Wall Street Journal Why do so many accountants fail to warn the public that the companies they audit are on the verge of collapse? Increasingly, experts are blaming inventory fraud. "When companies are desperate to stay afloat, inventory fraud is the easiest way to produce instant profits and dress up the balance sheet," says Felix Pomerantz, director of Florida International University's Center for Accounting, Auditing and Tax Studies in Miami. Even auditors at the top accounting firms are often fooled because they usually still count inventory the old-fashioned way, that is, by taking a very small sample of the goods and raw materials in stock and comparing the count with management's tallies. In addition, Mr. Pomerantz says, outside auditors can fail to catch inventory scams because they "either trust management too much or fear they will lose clients by being tougher." The problem is growing fast. On Friday, Comptronix Corp., for example, disclosed that inventory manipulations played a significant role in the scandal at the once-highflying Alabama electronics company. In November, William Hebding, its chairman and chief executive, told the Comptronix board that he and two other top officers had simply, though improperly, inflated profits by putting on the books as capital assets some expenses, such as salaries and start-up costs, related to the company's expansion. But on Friday, the company said the "fraudulent" accounting practices were started by making false entries to increase its inventory and decrease its cost of sales. Comptronix also said Mr. Hebding has been dismissed and its auditor, KPMG Peat Marwick, has resigned. Nationwide, tough economic times have sparked a fourfold increase in inventory fraud from five years ago, says Douglas Carmichael, a professor of accounting at City University of New York's Baruch College. Paul R. Brown, an accounting professor at New York University's graduate school of business, adds: "The recent rise in inventory fraud is one of the biggest single reasons for the proliferation of accounting scandals." Indeed, lawsuits charging accounting firms with fraud and malpractice have escalated to the point where the six biggest firms last year spent nearly $500 million9% of their U.S. audit revenue -- to defend themselves. Although audi-tors' failure to spot bad loans at financial institutions gets headlines, accounting experts term inventory fraud far more pervasive. How an audit can misfire is illustrated by the way Deloitte & Touche, the auditors of Laribee Wire Manufacturing Co., failed to realize that the New York copper-wire maker was buoying a sinking ship by creating fictitious inventories. Laribee was plagued by huge debt -- almost seven times its equity -- generated by a major acquisition in 1988. Meanwhile, its sales to the troubled construction industry, its major customer for copper wire, were declining. In 1990, Laribee borrowed $130 million from six banks. The banks say they relied on the clean opinion that Deloitte & Touche gave Laribee's financial statement for 1989, when the company reported $3 million in net income. A major portion of the loan collateral consisted of Laribee's inventories of the copper rod used to draw wire at its six U.S. factories. But after Laribee filed for bankruptcy-court protection in early 1991, a court-ordered investigation by other ac-countants, attorneys and bankruptcy specialists showed that much of Laribee's inventory didn't exist. Some was on the books at bloated values. Certain wire-product stocks carried at $2.20 a pound were selling at only $1.70 to $1.75 a pound. Shipments between plants were recorded as stocks located at both plants. Some shipments never left the first plant, and documentation supposedly showing they were being transferred to the second plant "appeared to be largely ficti-tious," the report to the court found. And 4.5 million pounds of copper rod, supposedly worth more than $5 million, that Laribee said it was keeping in two warehouses in upstate New York would have required three times the capacity of the buildings, the report said. "It was one of the biggest inventory overstatements I've ever seen," says John Turbidy, the court-appointed trustee. He estimates that inventory fraud contributed $5.5 million before taxes to Laribee's 1989 results. Absent this fraud and other accounting shenanigans, Laribee would have reported a $6.5 million loss instead of the profit, he adds. Laribee's previous top management declines to comment. Creating phantom inventory instantly benefits a company's bottom line. Subtracting the current inventory of parts and raw materials from year-earlier figures shows the supply costs of producing items for sale. This cost, plus labor, is deducted from sales to help calculate profit. By inflating current inventories with phantom items, a company reduces stated production costs and creates phony profits. Banks and other creditors sued Deloitte in state courts in Texas, Illinois, North Carolina and New York earlier this year for unspecified damages, charging it with malpractice and gross negligence in failing to spot the accounting mani-pulations at Laribee. A suit filed by Asarco Inc., a copper producer and Laribee creditor, accuses Mel Dobrichovsky, the Deloitte partner who oversaw Laribee's audit, of fraud in missing the inventory scam and other improper audit practices. "The auditor was either taken in or missed the obvious," Mr. Turbidy says. "Giving the auditors the benefit of the doubt, I assume that it was inexperience on their part because some who showed up at Laribee's plants were fresh out of college. Otherwise, how could they have overlooked such blatant inventory manipulations?" James T. Simmons, Laribee's former vice president for operations, says a firm later merged into Deloitte sent "three to five auditors with three years or less experience to the Camden, N.Y., and Jordan, N.Y. plants to check inventory." He recalls: "The faces kept changing and there was little continuity." According to several Laribee employees, a stand-ing joke at the plants was that the next outside auditor "would be fresh out of high school." Mr. Simmons adds that Mr. Dobrichovsky "never showed up at the plants" during annual inventory counts. Mr. Dobrichovsky, who left Deloitte at the end of 1990, declines to comment. Deloitte denies any wrongdoing and says the audits "were done in accordance with professional standards." In any event, the Laribee case isn't unusual. Experts say many companies overvalue obsolete goods and supplies. Others create phantom items in the warehouse to augment the assets needed as loan collateral. Still others count inven-tory that they pretend they have ordered but that will never arrive. In recent years, lawsuits have been filed against a lot of companies, including L.A. Gear Inc. and Digital Equipment Corp. Three class-action suits charge in federal district court in Los Angeles that L.A. Gear pumped up its inventories with "phantom sneakers," and one against Digital in federal court in San Jose, Calif., accuses it of failing to set aside reserves for obsolete inventory. L.A. Gear declines to comment, and Digital denies the allegations. As critics see it, unscrupulous managers can get auditors to swallow all kinds of ruses. In one case, auditors per-mitted company officials to follow the auditors and record where they were making test counts of inventory, Prof. Carmichael says. "Then the managers simply falsified counts for inventory that wasn't being tested by the auditors." In another case, the auditor spotted a barrel whose contents management had valued at thousands of dollars. Ac-tually, the barrel was filled with floor sweepings. The auditor forced the company to subtract the false amount from inventory, Prof. Carmichael says, "but it never occurred to the auditor that this was an egregious example of intentional and pervasive fraud. To be that blind suggests incompetence or worse." Prof. Carmichael adds that spotting inventory fraud requires bigger staffs than some accounting firms now have or are willing to send out to do inventory sampling. In the slow economy, the firms, facing reduced revenue growth and client demands for audit-fee concessions, have been pushing out partners and lower-level staff to cut costs. "With their jobs in peril, remaining auditors are less likely to make waves for fear of losing a client and possibly their jobs," says Howard Schilit, an associate professor of accounting at American University in Washington, D.C. According to professional standards, outside auditors are supposed to watch carefully how company personnel count inventory and make counts themselves for a representative sample. The sample usually ranges from 5% to 10%, experts say. But current auditing standards don't spell out the sample's size, which depends on the auditor's judgment, nor how the inventory should be counted, says the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, which sets the standards. Alan Winters, the institute's director of auditing research, says it is difficult if not impossible for an outside auditor to spot inventory fraud "if top management is directing it." But Mr. Pomerantz of the Florida center disagrees. "If auditors were more skeptical of management claims, partic-ularly in bad times, they would look at a far greater portion of the inventory in certain instances and do more surprise audits, which under the leeway of current standards nowadays are unusual," he says. Fights over how auditors should handle inventory have figured prominently in the woes of Phar-Mor Inc., the troubled deep-discount drugstore chain based in Youngstown, Ohio. It recently took a $350 million accounting charge to cover losses resulting from an alleged swindle by some former managers, who were dismissed last August. The company's surviving management and Coopers & Lybrand, its former outside auditor, have each filed lawsuits charging the other with negligently failing to detect inventory fraud and other financial manipulations at Phar-Mor. The suit by Coopers, filed in a state court in Pittsburgh, contends that previous management kept items in inventory ledgers that had already been sold, maintained a secret inventory ledger and created phantom inventory at many of the chain's stores. But a suit filed against Coopers in federal district court in Cleveland in October by Corporate Partners L.P. contends that Coopers is at fault for failing to catch the scams. Corporate Partners, which has a 17% stake in Phar-Mor, is an investment fund affiliated with Lazard Freres & Co., the investment bank. While recent charges concerning PharMor have cited the inventory-rigging problem, the Corporate Partners' suit has far more detailed allegations. Corporate Partners contends that Coopers, in a "gross departure from generally accepted auditing standards, observed the taking of inventory at no more than five stores" and "advised Phar-Mor, in advance, of the specific stores at which Coopers would observe" the inventory counting. Corporate Partners maintains that Phar-Mor then "refrained from making fraudulent adjustments at the five stores where it knew that the inventories would be observed . . . by Coopers. Instead, it Phar-Mor made its fraudulent adjust-ments to the inventory records of the vast majority of other stores that it knew in advance that Coopers would not review." On June 30, 1990, the fiscal year end, Phar-Mor's balance sheet "falsified (and overstated) inventory by more than $50 million," the suit alleges, adding, "Coopers closed its eyes to the evidence that would have revealed the false and inflated inventory adjustments." Eugene M. Freedman, Coopers's current chairman, contends that the suit lacks merit because the fund's own ac-countants studied Phar-Mor's finances before it invested in Phar-Mor in 1991. He adds that the fund's accountants spent little time discussing PharMor with Coopers's auditors. "They're trying to shift the blame for their inadequate due diligence and judgment" to Coopers, he contends. Phar-Mor said last August that it was the victim of a more than $400 million fraud-andembezzlement scheme by Michael Monus, a co-founder of the company and former president, and three other executives; all were discharged soon afterward. Phar-Mor and Mr. Monus recently filed for bankruptcy-court protection. In its suit, Corporate Partners said it would have also sued the company and Mr. Monus if they hadn't filed in bankruptcy court. Mr. Monus has de-clined to comment. David McLean, Coopers's associate general counsel, says the firm had to tell Phar-Mor managers where it was sampling inventories "because those stores had to be closed to do the count. You can't check a huge retail operation's inventories while the store is open." Sometimes, however, auditors fall for the most obvious ruses. Paul Regan, a forensic accountant in San Francisco often involved in court cases, recalls a Texas company being acquired by a California computer concern. He says the auditor test-counted two types of computer chips, finding 500 of one and 300 of the second at the acquired company. The next day, the acquired company's controller called the auditor and told him that "an hour after you left, 1,500 more chips of the first variety and 1,000 of the second arrived in a shipment," he says. But the auditor "never checked back to see if the new chips were for real. It was a complete scam and helped the acquired company double its reported profits," Mr. Regan says. --PUBLISHER: Dow Jones & Company Who killed Westinghouse Electric? Eventually Westinghouse would lend Youngstown-based Phar-Mor $150 million, as its go-go Financial Services division increased its portfolio of loans at a tremendous rate, generating large upfront fees, but also saddling the corporation with debt that would turn bad by the end of the decade. In this photo taken from the 1987 annual report, Westinghouse executives William Harper (left) and David Heilman (right) talk with Phar-Mor CEO David Shapira (second from left) and Phar-Mor President Michael Monus (short guy with dark tie). Mickey Monus