Remedies and the Psychology of Ownership

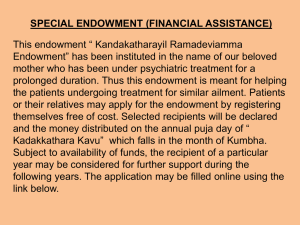

advertisement