12 Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector

advertisement

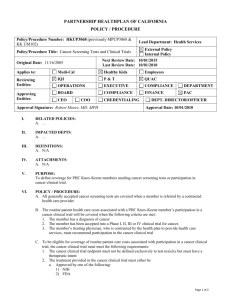

Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector 12 Authors: Mark S Blecheri Candy Dayii Sandy Doveiii Rob Cairnsiii Abstract This chapter examines trends in expenditure and funding of Primary Health Care services. It builds on previous models to develop an updated funding norm for Primary Health Care services in the public sector. Spending on public sector Primary Health Care services amounted to R297 per capita uninsured in 2006/07 and budgeted amounts rise to R395 per capita by 2010/11 (stated in 2007/08 prices). An updated funding norm is proposed of R401–R444 per capita (2007/08 prices) for visit rates ranging from 3 to 3.5 visits per person per year. The majority of districts are currently funded below the norm and progressive funding improvements are recommended. However, these also need to be linked to performance and efficiency. Inequities between districts are large with per capita annual expenditure ranging from R191 to R633. Nevertheless, the differences in per capita spending on Primary Health Care are gradually declining. These differing expenditure patterns point to the need for a better developed and more equitable approach to determining resource allocations to health districts. i National Treasury ii Health Systems Trust iii The Valley Trust 179 Introduction This chapter discusses recent trends in health budgets with The uninsured population numbers in districts were derived a particular focus on Primary Health Care (PHC) services using data drawn from Statistics South Africa’s General spending. The chapter consists of four parts. Household Surveys of medical scheme coverage by district.3 Trends in overall health care financing in South Africa, 1. with particular emphasis on provincial budgets and the District Health Services programme. More detail on the methodology is described elsewhere.4,5 Private spending data is drawn mainly from the annual reports of the Council for Medical Schemes, of which the most recent is for 2007/08.6 Whereas the public sector 2. Total and per capita PHC spending by health district. publishes forward budgets for three years in advance, the 3. Intra-district analysis from selected District Health private sector does not, and forward projections of private Expenditure Reviews. spending were based on 2007/08 baselines, to which has Development of an updated funding norm for public 4. sector PHC services. been added the CPIX inflation projections, plus 3% (of which 1% is membership growth). Out-of-pocket expenditure was based on Reserve Bank estimates of total private sector spending on health services and goods. The methodology Methodology for the PHC funding model is described later in the chapter. This chapter presents the most recently available information Trends in health expenditure and budgets on health service spending over the past three years and forward budgets over the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF). Expenditure and budget data of public sector health services are drawn mainly from publications and unpublished provincial databases of the National Treasury.1,2 These data sets have been updated to reflect the Overview of health sector funding public and private final published nine provincial budgets for 2008/09, final The latest published data, including some of the authors’ expenditure data for 2006/07 and pre-audited expenditure calculations and estimates of funding for health services in data for 2007/08. the South African public and private sectors are presented in Data are presented in nominal prices in terms of the standardised budget programme structure of provincial departments of health. Real growth estimates are based on the Consumer Price Index (CPIX) measure to adjust for inflation to 2007/08 prices.2 Local government expenditure data is drawn from the local government database of the National Treasury. The analysis of district-based funding is based on the five core provincial PHC sub-programmes (of programme 2) within the official budget structure, with the addition of local government ‘own’ contributions to health. Pre-audited spending data was downloaded from Table 1. The table shows that funding flows through financial intermediaries in millions of Rands. Estimated health services funding will exceed R200 billion by 2009/10 equivalent to 8.4% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Over the six year period from 2004/05 to 2010/11 funding is anticipated to grow 7% annually in real terms through public sector financing streams (from R48 billion to R97 billion). Spending growth in the private sector is projected to grow from R78 billion to R129 billion or 3.2% annually in real terms. This is considerably lower than the six proceeding years when private sector funding growth averaged 6.4% per annum. the financial system (Vulindlela) for 2007/08, and the many There remains however a very large per capita difference thousands of cost centres were grouped according to facility between public and private financing. The ratio between location and aggregated into a particular health district. public provincial and private medical schemes per capita Some provinces in their financial systems did not classify expenditure is predicted to decline from 7 to 5.2 over all PHC expenditure by district or facility and such residual the period 2004/05 to 2010/11, but this latter ratio is still amounts were allocated proportionally to districts. This above the levels that existed in the mid 1990s. The forward had the potential for introducing some bias. However, the estimates should be treated with caution as there is residual amounts were generally small in relation to the total uncertainty particularly for the private sector. expenditure. The term PHC is used here in a narrow sense of primary level health services delivered by departments of health, and does not include the broader conceptualisation of PHC such as in the Alma Ata Declaration. 180 Donor funding, although contributing only 2% of total health funding, is growing strongly above 20% annually. Personal communication, South African Reserve Bank, 2007. Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector Public sector funding for health services comprises 3.5% where most PHC services are located are estimated to of the GDP and 14.1% of total government expenditure, grow by 8.2% annually. Forecasted spending on health excluding interest payments in 2008/09 (12.1% otherwise) facilities management (infrastructure) is estimated to and is expected to grow by 6.1% in real per capita terms over increase by 19.4% annually and emergency medical services the period. (ambulances) by 12.4% annually. This is a reflection of the recent budget priorities of hospital revitalisation and a new, Provincial departments of health faster and responsive ambulance service. The relatively high Provincial health budgets are shown in Table 2. Budgets following an improved occupation-specific remuneration are estimated to grow at 7.6% in real terms annually over dispensation, where the packages of health professionals the period 2004/05 to 2010/11. District health services, (e.g. nurses and doctors) have been increased. real growth rates are partly because of higher personnel costs Table 1: Overall health sector funding public and private sectors* (Rand million) 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 Annual real change National Department of Health core 1 011 1 029 1 131 1 210 1 414 1 472 1 562 2.1% Provincial departments of health 40 526 47 015 53 648 62 594 69 440 77 164 86 103 7.6% 1 320 1 557 1 683 1 831 2 001 2 278 2 460 5.3% 174 188 199 211 224 237 251 1.0% Local government (own revenue) 1 247 1 317 1 478 1 566 1 597 1 629 1,662 3.8% Workmens Compensation 1 322 1 414 1 499 1 574 1 653 1 735 1 822 3.7% 489 520 554 589 627 753 938 5.8% 1 423 1 565 1 721 1 833 2 134 2 350 2 503 4.3% 47 511 54 605 61 913 71 408 79 090 87 619 97 302 7.0% Medical schemes 52 211 54 905 58 349 64 654 72 736 78 918 85 153 3.0% Out-of-pocket 23 125 25 480 27 231 29 954 33 699 36 563 39 452 3.8% 1 879 1 956 2 056 2 179 2 452 2 660 2 870 1.9% 898 935 982 1 041 1 172 1 271 1 372 1.9% 78 113 83 277 88 619 97 829 110 058 119 413 128 847 3.2% 947 986 2 000 3 000 3 500 4 000 4 240 21.9% 126 571 138 867 152 532 172 237 192 648 211 032 230 389 4.9% Rand million Public sector Defence Correctional services Road Accident Fund Education Total public Private sector Medical insurance Employer private Total private Donors or Non-governmental organisations Total Total as % of GDP 8.8% 8.8% 8.4% 8.4% 8.4% 8.4% 8.4% Public as % of GDP 3.3% 3.5% 3.4% 3.5% 3.5% 3.5% 3.5% Public as % of total government expenditure (noninterest) 13.9% 14.0% 14.0% 14.2% 14.1% 14.2% 14.1% Private financing as % of total 61.7% 60.0% 58.1% 56.8% 57.1% 56.6% 55.9% Public sector real Rand per capita 2007/08 prices 1 404 1 542 1 651 1 750 1 811 1 899 1 999 6.1% Note: *Numbers are stated in nominal rand values (Rand million) and include flows through funding intermediaries. Source: National Treasury publications and databases; authors’ calculations.1,2,6 181 12 Table 2: Provincial departments of health: Spending and budgets Rand million 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 Annual real growth 2004/052010/11 Administration 1 703 1 627 1 922 2 038 2 543 2 593 2 782 3.0% District Health Services 16 016 18 387 21 053 25 602 28 241 31 381 35 065 8.2% Emergency Medical Services 1 341 1 758 2 059 2 515 2 919 3 340 3 694 12.4% Provincial Hospital Services 10 422 11 696 13 055 14 683 15 799 17 637 19 517 5.4% Central Hospital Services 7 009 8 161 8 757 9 395 9 627 10 741 12 057 3.9% Health Training and Sciences 1 229 1 556 1 779 2 111 2 554 2 601 2 809 9.0% 571 772 819 992 1 131 1 169 1 331 9.3% 2 252 3 103 4 251 4 992 6 683 7 760 8 909 19.4% 40 526 47 015 53 647 62 274 69 440 77 164 86 103 7.6% Health Care Support Services Health Facility Management Total Source: National Treasury publications and databases.1,2 contributions for health services, spending on upgrading District health services PHC facilities (programme 8) and on PHC training The District Health Services programme is the largest programme in the budgets of provincial departments of health. The composition of the programme is shown in Table 3. (programme 6). Together these will amount to R15.6 billion in 2008/09 (R12.9 billion on the core five sub-programmes) or R358 per capita uninsured person. Spending is projected to rise from R263 per capita in real terms in 2004/05 to R395 in 2010/11. PHC spending by this definition amounts Spending on PHC services, using one potential definition, is to 22% of total health spending in 2008/09. This figure shown in Table 4. This approach includes the first five core excludes HIV and AIDS and district hospitals, and would be sub-programmes of Table 3 and adds local government higher if these were included. Table 3: District health services Annual real growth 2004/052010/11 Rand million 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 District Management 1 030 963 983 1 166 1 451 1 617 1 776 4.0% Community Health Clinics 3 299 3 854 4 056 5 302 6 486 7 148 7 944 9.9% Community Health Centres 1 796 2 074 2 346 2 808 3 095 3 404 3 696 7.1% CommunityBased Services 579 762 1 040 1 188 1 276 1 453 1 607 12.6% Other Community Services 424 512 558 605 614 669 816 5.9% Subtotal five core PHC subprogrammes 7 128 8 164 8 983 11 069 12 923 14 291 15 838 8.4% HIV and AIDS 1 147 1 692 2 376 3 051 3 593 4 310 5 068 21.6% 159 172 170 187 223 253 252 2.5% Coroner Services 3 7 313 612 394 428 485 117.0% District Hospitals 7 552 8 302 9 131 10 575 11 003 12 024 13 411 4.5% 16 016 18 387 21 053 25 602 28 241 31 381 35 065 8.2% Nutrition Total Source: National Treasury publications and databases.1,2 182 Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector Table 4: Public sector Primary Health Care services expenditure Rand million 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 7 128 8 164 8 983 11 069 12 923 14 291 15 838 8.4% Local government own revenue 1 247 1 317 1 478 1 566 1 597 1 629 1 662 -0.4% Community health facilities 445 588 620 968 984 1 467 1 515 16.4% 65 85 74 148 133 199 213 15.6% Five core PHC subprogrammes 2004/05 Annual real growth 2004/052010/11 PHC training Total 8 885 10 154 11 156 13 751 15 637 17 586 19 229 8.0% Rand per capita uninsured 224 255 277 337 380 424 460 7.0% Rand per capita real 2007/08 prices 263 287 297 337 358 381 395 7.0% 21.3% 21.0% 20.2% 21.5% 22.0% 22.3% 21.9% PHC as proportion of total Source: National Treasury publications; provincial and local government databases.1,2 PHC spending has grown by 8.6% annually in real terms over in which some districts only spent R41 per capita.8,9 Of the past three years from 2004/05 to 2007/08. During the the 10 lowest funded districts, three are in the Free State same time PHC visits have increased by 1.1% per annum from (Lejweleputswa, Thabo Mofutsanyane and Fezile Dabi), two 101 million to 104 million. are in the Eastern Cape (Alfred Nzo and Oliver Tambo), two in Mpumalanga (Gert Sibande and Nkangala) and one each Inter-district inequities in Northern Cape (Siyanda), KwaZulu-Natal (Amajuba) and Limpopo (Greater Sekhukhune). There are large inequities in funding across districts.7 Table 5 shows per capita (uninsured) spending in each of the Greater detail of health district spending by sub-programme health districts of South Africa over the past three years. The in 2007/08, expressed in per capita terms is shown in best funded district is Namakwa in Northern Cape (R633 Table 6. Metropolitan districts are financed 28% higher per capita uninsured in 2007/08) and the worst funded is than other districts (R356 vs R279 per capita) partly because Lejweleputswa in the Free State at R191 per capita. The ratio of local government revenues. This table also shows total of these is 3.3, which represents a large difference, but is spending on the district management sub-programme. smaller than the 9.4 fold difference found in a 2001 study Table 5: District Primary Health Care spending per capita (Rands), 2005/06-2007/08* District 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 Annual real growth 2005/06 to 2007/08 498 633 16.3 DC6 Namakwa 415 DC5 Central Karoo 294 321 526 26.1 DC1 West Coast 373 464 466 5.3 CPT City of Cape Town 354 384 445 5.6 DC4 Eden 325 347 435 9.0 DC43 Sisonke 239 273 416 24.3 DC38 Ngaka Modiri Molema (Central) 280 328 398 12.2 DC16 Xhariep 331 361 387 1.9 DC7 Pixley ka Seme 236 294 376 18.9 JHB City of Johannesburg 288 313 371 7.1 2.6 visits per capita uninsured, provincial quarterly reporting and District Health Information System (DHIS). 183 12 District 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 379 320 367 Annual real growth 2005/06 to 2007/08 DC39 Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati (Bophirima) -7.2 ETH eThekwini 282 305 365 7.2 DC45 Kgalagadi 253 277 353 11.3 DC2 Cape Winelands 272 291 353 7.4 DC40 Dr Kenneth Kaunda (Southern) 292 311 342 2.1 DC27 Umkhanyakude 273 308 340 5.1 DC10 Cacadu 193 223 339 24.7 TSH City of Tshwane 245 311 335 10.3 DC3 Overberg 212 246 320 15.6 DC9 Frances Baard 202 261 314 17.6 DC29 iLembe 195 217 310 19.0 DC12 Amathole 251 265 305 3.9 DC13 Chris Hani 235 256 303 7.1 DC36 Waterberg 187 205 303 20.0 DC34 Vhembe 217 203 301 10.9 DC37 Bojanala Platinum 222 280 290 7.9 DC33 Mopani 218 235 290 8.7 DC46 Metsweding 198 150 287 13.4 DC26 Zululand 201 216 280 11.2 DC28 Uthungulu 227 229 278 4.2 DC23 Uthukela 171 195 277 19.7 DC22 UMgungundlovu 216 236 276 6.4 DC17 Motheo 254 296 274 -2.1 EKU Ekurhuleni 243 286 273 -0.2 DC21 Ugu 204 217 272 8.9 NMA Nelson Mandela Bay Metro 220 241 264 3.1 DC24 Umzinyathi 198 227 263 8.7 DC35 Capricorn 165 193 256 17.6 DC32 Ehlanzeni 164 187 256 17.8 DC14 Ukhahlamba 186 209 239 6.6 DC48 West Rand 242 221 236 -6.9 DC42 Sedibeng 188 196 233 4.9 DC20 Fezile Dabi 228 222 230 -5.3 DC31 Nkangala 160 195 226 12.1 DC15 O.R. Tambo 188 199 223 2.4 DC47 Greater Sekhukhune 121 163 221 27.2 DC25 Amajuba 151 177 220 13.6 DC30 Gert Sibande 137 185 211 16.9 DC19 Thabo Mofutsanyane 206 213 211 -4.6 DC8 Siyanda 119 150 206 23.8 DC44 Alfred Nzo 177 202 198 -0.5 DC18 Lejweleputswa 187 190 191 -4.7 Total 232 256 302 7.6 Note: * Ranked from highest to lowest per capita spending in 2007/08. * Includes five core sub-programmes and local government but excludes health facilities management, PHC training, HIV and AIDS and district hospitals sub-programmes. Source: Analysis by authors of 2007/08 expenditure data drawn from Vulindlela and National Treasury local government databases. 184 Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector Table 6: Primary Health Care spending per capita uninsured 2007/08* Rand thousand Rand per capita uninsured Province EC FS GP KZN LP District management District Clinics and community health centres Community based and other community services Local government excluding transfers Total District management DC10 Cacadu¤ 146 143 29 21 339 52 541 DC12 Amathole 31 224 39 11 305 51 205 DC13 Chris Hani 61 201 41 0 303 50 127 DC14 Ukhahlamba 60 126 53 0 239 19 396 DC15 O.R.Tambo 35 155 33 0 223 60 496 DC44 Alfred Nzo 43 123 25 7 198 26 501 NMA Nelson Mandela Bay Metro 12 170 53 29 264 10 181 DC16 Xhariep 56 173 158 0 387 6 920 DC17 Motheo 18 205 51 0 274 10 882 DC18 Lejweleputswa 21 104 65 0 191 13 702 DC19 Thabo Mofutsanyane 16 38 155 1 211 11 988 DC20 Fezile Dabi 16 132 81 0 230 6 708 DC42 Sedibeng 29 183 21 0 233 23 188 DC46 Metsweding 90 149 48 0 287 14 968 DC48 West Rand 52 110 62 13 236 33 691 EKU Ekurhuleni 16 126 20 112 273 31 801 JHB City of Johannesburg 23 200 54 95 371 59 710 TSH City of Tshwane 69 136 54 76 335 109 116 DC21 Ugu 26 186 59 1 272 17 408 DC22 UMgungundlovu 18 173 47 38 276 15 464 DC23 Uthukela 21 190 45 21 277 12 510 DC24 Umzinyathi 17 180 66 0 263 7 435 DC25 Amajuba 21 145 45 9 220 11 225 DC26 Zululand 21 217 42 0 280 16 322 DC27 Umkhanyakude 19 204 117 0 340 10 933 DC28 Uthungulu 13 186 62 16 278 10 359 DC29 iLembe 13 235 49 13 310 7 728 DC43 Sisonke¤ 123 233 60 0 416 36 755 ETH eThekwini 7 209 61 89 365 17 604 DC33 Mopani 14 215 58 3 290 14 051 DC34 Vhembe 19 221 56 5 301 22 782 DC35 Capricorn 23 193 33 7 256 25 986 DC36 Waterberg 52 160 83 8 303 29 081 DC47 Greater Sekhukhune 41 153 26 0 221 40 128 185 12 Rand thousand Rand per capita uninsured Province MP NC NW WC District District management Clinics and community health centres Community based and other community services Local government excluding transfers Total District management DC30 Gert Sibande 41 149 0 21 211 32 500 DC31 Nkangala 41 167 0 18 226 40 638 DC32 Ehlanzeni 39 207 0 9 256 56 050 DC45 Kgalagadi¤ 163 169 5 17 353 28 322 DC6 Namakwa 92 502 38 1 633 8 759 DC7 Pixley ka Seme 21 315 35 4 376 3 355 DC8 Siyanda 27 184 9 -14 206 5 389 DC9 Frances Baard 16 199 78 22 314 5 104 DC37 Bojanala Platinum 44 220 15 11 290 49 118 DC38 Ngaka Modiri Molema (Central) 75 303 14 6 398 52 859 DC39 Dr Ruth Segomotsi Mompati (Bophirima) 87 267 14 0 367 38 027 DC40 Dr Kenneth Kaunda (Southern) 63 241 17 21 342 30 964 CPT City of Cape Town 27 289 38 92 445 65 814 DC1 West Coast 47 251 166 2 466 10 254 DC2 Cape Winelands 29 283 39 2 353 14 746 DC3 Overberg 0 312 7 0 320 0 DC4 Eden 30 304 49 51 435 12 096 DC5 Central Karoo 0 388 137 1 526 0 33 193 44 32 302 1 342 887 Total Note: * The table shows PHC spending per capita by component. The last column shows spending on the District Management programme in thousands of Rand. ¤ It is likely that some districts have misclassified district management expenditure (e.g. Cacadu, Kgalagadi and Sisonke). Source: Analysis by authors of 2007/08 expenditure data drawn from Vulindlela and National Treasury local government databases. District Health Expenditure Reviews A useful tool for the district management team to plan and Calculating unit costs and comparing them among budget effectively is the District Health Expenditure Review facilities of similar types. This can assist in highlighting (DHER). The district level is a key level of decentralised inefficiencies through matching workloads to personnel management of PHC services in the health system. One way distribution and budgets. One of the most important in which it can be progressively strengthened is for better efficiency gains that can be made in a district is to management of resources, especially financial, and the DHER optimally match personnel distribution to workload. can assist with this (see Figure 1). Examining inequities between sub-districts. The DHER is useful in providing information to district Monitoring trends in performance. managers in making decisions in: Balancing between services provided in PHC facilities Distribution of expenditure among different facilities and the district hospital (some districts treat too and different services in the district. many PHC patients in district hospital outpatients and consequently spend too high a share of the district budget on the district hospital). 186 Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector Figure 1: Data required for the District Health Expenditure Review Activity: The DHER relies on the combination of the activity, personnel, financial and services information in order to provide indicators: Personnel: In-patients Out-patients Hours worked Usable beds Number of Nurses and doctors DHER Financial: Human Resources Goods and Services Transfer Payment Capital Items Services: In-patients Out-patients Hours worked Usable beds patient day equivalents bed occupancy average length of stay expenditure per capita expenditure per visit utilisation per capita workload variances Source: Figure developed by authors from The Valley Trust. Spending on programmes such as HIV and AIDS, In developing this model some of the previous approaches nutrition, community health workers, environmental used for PHC modelling in South Africa were reviewed and health, malaria control and others. built on.10-16 One of the most useful recent estimates of a Spending on medicines, laboratory services, security, maintenance and patient food. Once district managers are well informed about workloads, unit costs, spending, personnel distribution and other key indicators in the district, they are better able to optimally allocate resources in the district. national funding norm for PHC was R310–R420 per capita (2007/08 prices).,17 The developed model follows. District office One potential structure for a district office is shown in Table 7. Further refinement would be worthwhile here and it is possible that greater provision should be made for sub-district management and facility supervision, and that Modelling a funding norm for Primary Health Care Norms and standards are one mechanism for achieving greater equity and improved performance for PHC. The last part of the chapter develops a model and potential funding norm for PHC. A simplified version of the model is presented in three main parts. the specialist support proposed is something to aim for rather than what districts currently have. The model makes provision for 40% non-personnel costs including transport and office costs, rental, telephone, etc. The model suggests that a reasonably staffed district office can be established for around R24.7 million (2007/08 prices). Currently about half of the 52 health districts exceed this level of spending on the district office and half spend less than this (see Table 6, last column). However, given that most district 1. District office. 2. Facility-based care (including clinics, community health of the existing expenditure against this sub-programme centres and mobiles). has been misclassified. 3. offices in the country are relatively weak, it is likely that some Community-based services (including some additional public health programmes). This work was based particularly on rising utilisation levels and on the extent to which PHC work was performed at higher unit costs within district hospitals. 187 12 188 558 306 1 2 District Manager Secretary 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 HIV Deputy Director STDs Deputy Director Child health Deputy Director Maternal health Deputy Director Family planning Deputy Director Health promotion Deputy Director Mental health Deputy Director Infectious diseases Deputy Director and outbreak response Chronic diseases of lifestyle Deputy Director Trauma Deputy Director 2 1 1 1 1 1 Health service planning and evaluation Community Paediatrician Community Psychiatrist Community Obstetrician Surgeon Physician Source: Modelling developed by authors. 2 Clinical services Director and support + Secretary Health service management and support 1 TB Deputy Director 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 2 Information Officers 136 338 2 Public health Specialist + Registrar 558 798 558 798 558 798 558 798 558 798 822 377 556 100 411 188 411 188 714 625 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 411 188 822 377 411 188 272 676 Total Non-personnel Personnel: total Clinical Engineer 78 2 4 Maintenance 1 Drivers 8 2 2 2 1 4 8 1 8 1 8 1 N Manager Transport and logistics office Store workers District Pharmacist Pharmacy Security Kitchen Groundsmen Cleaning Domestic Clerks Deputy Director Personnel Clerks Deputy Director Procurement 1 029 422 Clerks 546 367 2 Director Finance Health Programme Director and Assistant 449 718 558 306 Cost (Rand) Public health and programmes 72 376 Unit cost N Table 7: Potential structure for district office 136 338 72 376 238 462 72 376 60 287 65 129 60 287 60 287 72 376 411 188 72 376 411 188 72 376 473 991 Unit cost 24 754 355 7 072 673 17 681 682 272 676 289 504 238 462 579 008 449 718 120 575 130 258 60 287 241 150 579 008 411 188 579 008 411 188 579 008 473 991 Cost (Rand) Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector Facility-based Primary Health Care services A model for facility-based services for a district of 100 000 uninsured persons and for the country has been developed. The model is based on nurse-based clinics, community health centres and mobiles. Seventy percent of visits are managed in nurse-led clinics, 25% in community heath centres and 5% in mobiles. There are approximately seven clinics for each community health centre in a tiered system by which the community health centre supports the clinic with a fulltime doctor, radiology, laboratory, midwife, rehabilitation and other services. The model has various components. The personnel component (see Table 8) builds on work done for the 1995 Committee of Inquiry and a PHC staffing model linked to workload ratios developed by Daviaud.,10 Table 8: Personnel in a district of 100 000 uninsured persons* Staff required Staff Wage Total Rand thousand Total per 100 000 population Doctor 5 466 981 2 232 22 Midwife 3 181 558 567 6 Professional Nurse 49 181 558 8 930 89 Enrolled Nurse 13 90 169 1 185 12 Enrolled Nursing Assistant 15 68 304 1 028 10 9 68 304 602 6 10 109 650 1 106 11 General Assistants 7 60 287 424 4 Security 3 60 287 181 2 Pharmacist 2 181 558 363 4 Social Worker 1 148 406 148 1 Dentist 2 466 981 934 9 Dental Therapist 1 90 169 90 Oral Hygienist 1 148 406 148 1 Pharmacy Assistant 2 90 169 180 2 Physiotherapist 1 148 406 74 1 Physio Assistant 1 90 169 90 1 18 433 183 Counsellor Administrative Total 126 Note: *Based on visit rate of 3.5 with 70% visits managed in nurse-based clinics. Source: Author’s modelling; Department of Health, 1996;10 Personal communication, E Daviaud, South African Medical Research Council, 2006. Personal communication, E Daviaud, South African Medical Research Council, 2006. 189 12 PHC costs have risen with the introduction of the new Occupation Specific Dispensation for nurses from 1 July 2007, which for the first time introduces a new Community-based services and programmes remuneration dispensation for appropriately qualified A simple model for community-based and public health PHC nurses. Specific sub-component models have been services based on environmental health, community health developed for medicines, capital (buildings and equipment) workers, school health and some others has been developed and other aspects (see Table 9). The medicines model is (see Table 10).18,19 These suggest the country should be based on an average dispensing of 1.5 medicines at spending about R3.1 billion annually on such programmes, R8 unit cost for clinics and three items averaging R11 while the actual expenditure is R2.2 billion. each in community health centres. The methodology for capital builds on an approach developed by Bennett Table 10: Community-based services cross-checked against a set of recent facility builds. Table 9: Cost per visit Clinic Personnel Medicine 42 Community Health Centre 91 Mobile Total Programme Basis Environmental health 1:15 000 661 774 Community health worker 1:250 households 466 000 2 community health nurses per community health centre 175 897 39 11 31 11 Capital 9 13 10 Equipment 4 10 4 Other nonpersonnel non-capital (NPNC) 10 16 10 Cost per visit 77 161 74 Community nursing School health Health promotion 97.80 Source: Authors’ modelling; Personal communication, V Titus, Department of Health, 2004; Personal communication, R Bennett, Department of Health, 2005. Putting together unit costs and visit rates, the total model suggests a funding norm for facility-based services of R293–R336 per capita at visit rates ranging from 3.0–3.5 per Cost (R000) 462 324 R3 million per district 159 000 Nutrition 172 059 Malaria 100 000 Communitybased mental health rehab Public health programmes Total Cost per capita Rand 10 000 places 365 000 500 000 3 062 053 76 Source: Authors’ modelling; Haynes, 2004;18 Friedman, 2005.19 uninsured person per annum. Actual spending in 2007/08 was R192 per capita for facility-based services (at utilisation rate of 2.6) and was below R293 per capita in all but six districts. If visit rates were to rise further to 3.85 (as proposed by a previous review) costs would be correspondingly higher (R366).17 Total Primary Health Care funding norm If one combines the district office, the facility-based services and the community-based and public health services, a norm of R401–R444 per uninsured person in 2007/08 The model suggests that South Africa has a significant prices is proposed, depending on visit rate (ranging from shortage of community health centres (the higher level of 3–3.5). If utilisation rises further to 3.85 as suggested by PHC which provides support for clinics through radiology, a Department of Health (DoH) model, then costs would be obstetric, laboratory, rehabilitation, minor theatre and other even higher (R474).17 However actual utilisation was only services) with a shortfall of 146 community health centres. 2.6 visits per capita uninsured in 2006/07 and spending is Some of these services are currently provided by district rising faster than utilisation, suggesting some inefficiencies hospitals. in delivery. Personal communication, V Titus, Department of Health, 2004. Personal communication, R Bennett, Department of Health, 2005. 190 Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector Table 11: Calculated Primary Health Care funding norm per capita (2007/08 prices)* This suggests that funding for PHC services does need to rise progressively in all three compartments (i.e. district office, facility-based services, community-based services Norm at visit rate of 3 per capita uninsured Norm at visit rate 3.5 and programmes). Strengthening district offices is needed Facility-based 293 336 a future role for District Health Authorities as public District office 32 32 purchasers is being discussed as part of current debates Community-based 76 76 around National Health Insurance as well as earlier policy 401 444 proposals.10 Strengthening of facility-based services is likely 3 3.5 Cost per capita uninsured Total per capita uninsured Visit rate to improve and firmly establish the district tier. In addition, to encompass higher visit rates and improved resourcing. Note: * Per capita uninsured persons. * Excludes HIV services. * District office norm here is an average; in fact the authors propose a fairly standard district office of R25 million budget per annum. Funding of community-based and public health programmes Source: Authors’ modelling based on components above and varying visit rates. funding of HIV and AIDS is a large component additional also falls short of even the relatively small number of areas covered. Strengthening this component may have an important role in improving health status. Note that the to the basic PHC model, and has not been included in this chapter.22,23 Data from Table 3 shows that by 2010/11 HIV Discussion and AIDS dedicated budgets will add 32% to the cost of the The data shows that spending on PHC services is increasing the 16% in 2004/05. However, HIV and AIDS cost models relatively strongly at 7% per annum in real terms over the suggest that this will continue to rise and this progressively period from 2004/05 to 2010/11. This is encouraging given increasing proportion may support the case for progressive the importance of PHC in improving population health. integration of HIV and AIDS programmes into comprehensive However, spending is increasing at a significantly faster pace PHC services. five core PHC sub-programmes and will have doubled from than visits and more information is required to determine whether South Africa is receiving value for money and better quality of care for the increased expenditure. The data points to significant inequities in funding between districts and to specific districts funded well below the average. Provincial departments of health need to develop Health outcomes for South Africa are in many cases well objective methods to allocate resources more equitably below comparable peer countries. South Africa has relatively between districts, such as through district-based resource low tuberculosis (TB) cure rates and sub-optimal maternal allocation formula (e.g. Resource Allocation Working Party and child health survival. South Africa should therefore (RAWP) formula in the United Kingdom).24 However, in the review whether there is sufficient focus on the correct short-term, consideration should also be given to the very application of effective interventions within our PHC different workloads between districts. 20,21 services. Part of the increasing cost in 2007/08 was related to the long anticipated improved personnel remuneration for nurses, such as occupation-specific dispensation. An unresolved dilemma is whether PHC services in metropolitan districts should be provincialised or devolved. Beyond the debates around functional integration and Spending on PHC services amounted to approximately R302 decentralisation, PHC services are considerably better per capita uninsured in 2007/08 (as per Table 5) or R337 resourced in metropolitan areas (28% higher, as per Table 5 including infrastructure and training (as per Table 4). A and Table 6) because of stronger local government revenue funding norm of R401–R444 is proposed (as per Table 11), capacity. Provincialisation of PHC services risks losing access depending on utilisation (visit) rates. The revised norm is to local government revenue streams. higher than that of a previous estimate undertaken with the DoH (R310–R420 per capita) despite using lower utilisation rates.17 This difference arises from the higher unit costs Conclusion associated with the normative approach used in this model as opposed to the baseline unit costs derived from DHERs in Spending and budgets for PHC services are growing at 7% the earlier model. Also the new model uses higher personnel per capita per annum in real terms and constitute over unit costs, includes a district office component and a wider 20% of public sector health expenditure. The budget for set of community-based services. PHC is projected to increase to R19.2 billion by 2010/11. 191 12 There is still substantial inequity between districts with the Greater attention must be given to making every district ratio between the best funded and worst funded districts a cost centre in the financial management system and currently at 3.3, although this is a significant improvement to ensuring that all PHC expenditure is recorded in the from the ratio of 9.4 in 2001/02. The ten worst funded financial system in a manner that is linked to a district. health districts have been listed in this chapter. The district health authority is the key management authority but is to improve their capacity and skills in budgeting funded at less than the proposed funding norm in at least and finance as well as planning and programme half of districts. District health authorities will need to be management and support. considerably strengthened over the next decade, particularly if they are to also play a role as public purchasers of general practitioner services. District structures must be progressively strengthened Greater use must be made of the DHER, which is a useful tool for managers to review district spending, to better The DHER is a useful tool for district managers to understand inform their planning and budgeting. spending in their districts and plan services and budgets appropriately. Funding for facility-based services is still highly variable across districts. The model suggests South Acknowledgements Africa has a shortfall of 146 community health centres. The The authors wish to acknowledge inputs from Megan costing model suggests community-based and public health Govender, Nomkhosi Zulu, Keith Wimble and the reviewers. programmes appear to be under-funded by at least one billion rand. A funding norm for PHC services of R401–R444 per capita uninsured per annum is proposed in 2007/08 prices. This norm is based on a particular model district with clinics and community health centres in particular distributions. In this model 75% of consultations are managed by basic nurse-operated clinics. Although government budgets for PHC in 2008/09 are approaching the lower utilisation funding norm (there is a further R3 billion gap if visit rates rise to 3.5) some health performance indicators are still poor, such as TB cure rates, maternal and child mortality rates and waiting times. This, along with rising unit costs over the past three years, suggests inefficiencies and problems with quality and outcomes, which require substantial attention from district and PHC managers. Recommendations It is recommended that: PHC budgets must be progressively strengthened towards the funding norm of R401–R444 per capita uninsured taking into account district and facility performance and efficiency. District offices, facility-based services and programmes all need strengthening. A more systematised approach to district funding must be adopted to reduce large inequities between districts. Efficiency, performance and outcomes need attention noting that spending has risen faster than utilisation rates over the past three years. 192 Primary Health Care Financing in the Public Sector References 1 2 3 4 5 6 National Treasury. Provincial budgets and expenditure review 2003/04–2009/10. Pretoria: National Treasury; 2007. URL: http://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/ speeches/2007/2007090501.pdf 14 Brijlal V, Hensher M. Costing of the comprehensive package of Primary Health Care services. Pretoria. Department of Health; 1998. 15 Kraus R. Final report on optimal district personnel and skills mix requirements for delivery of Primary Health Care services. Johanesburg; 1998. 16 Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2005. URL: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/ P0318July2005.pdf Collins DH, Donaldson DS, Lewis EM. Primary Health Care costing tool, version 3. Pretoria: Management Sciences for Health, Equity Project. USAID; 2000. 17 Baron P, Day C, Monticelli F, editors. District Health Barometer 2006/07. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2007. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/publications/717 Department of Health and Health Economics Unit. Financial resource requirements for a package of Primary Health Care services in the South African public sector. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2004. 18 Haynes R. Financing environmental health services in South Africa. Health Systems Trust and Department of Health. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2004. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/ehs.pdf 19 Friedman I. Community health workers. In Health Systems Trust. South African Health Review, 2005. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2005. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/sahr05_ chapter13.pdf 20 Presidency of Republic of South Africa. Development indicators mid-term review. Pretoria: Presidency Republic of South Africa; 2007. National Treasury. Budget review 2008. Pretoria: National Treasury; 2008. URL: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/ national%20budget/2008/review/Default.aspx Day C, Gray A. Health and related indicators. In: Harrison S, Bhana R, Ntuli A, editors. South African Health Review 2007. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2007. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/chap15_07.pdf Registrar of Medical Schemes. Annual report of the Council of Medical Schemes 2007/08. Pretoria: Council for Medical Schemes; 2008. URL: http://www.medicalschemes.com/Publications/ ZipPublications/Annual%20Reports/Annual_Report_20078.pdf 7 McIntyre D, Muirhead D, Gilson L. Geographic patterns of deprivation in South Africa: informing health equity analyses and public resource allocation strategies. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17(suppl1):30–39. 21 World Health Organization. World health statistics 2007. Geneva: WHO; 2007. URL: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat2007/en/index. html 8 Blecher MS, Thomas S. Health care financing. In: Ijumba P, Day C, Ntuli A, editors. South African Health Review 2003/04. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2004. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/chap3_06.pdf 22 Department of Health. HIV and AIDS and STI strategic plan for South Africa, 2007–2011. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2007. URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/misc/stratplan-f.html 9 Thomas S, Mbatsha S, Muirhead D, Okorofor O. Primary Health Care financing and need across districts in South Africa. Local Government and Health Project Consortium. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2004. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/uploads/files/phcfin.pdf 23 Cleary S, Blecher MS, Boulle A, et al. The costs of the National Strategic Plan on HIV & AIDS and STI, 2007–2011. Document prepared for Department of Health. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2007. 10 Department of Health. Restructuring the national health system for universal Primary Health Care. Pretoria: Department of Health; 1996. URL: http://www.hst.org.za/pphc/Phila/nhsphc2.htm 24 Mays N, Bevan G. Resource allocation in the health service: a review of the methods of the Resource Allocation Working Party (RAWP). Occasional papers on social administration, No 81. London: Bedford Square Press; 1987. 11 Department of Health. Comprehensive package of PHC services. Pretoria: Department of Health; 1998. 12 University of Witwatersrand, Centre for Health Policy. Costing of core package of Primary Health Care services; 1998. 13 Department of Health. The primary care package for South Africa - a set of norms and standards. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2000. URL: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/policy/norms/contents. html 193 12 194