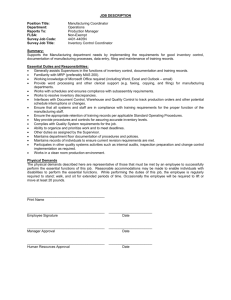

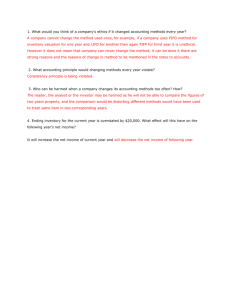

production and inventory management journal

advertisement