typologies and case studies report 2013

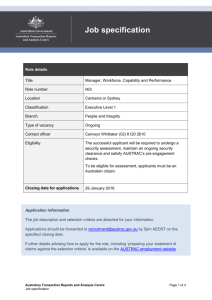

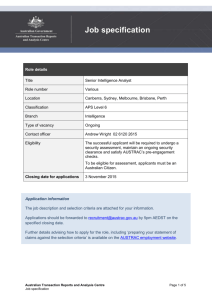

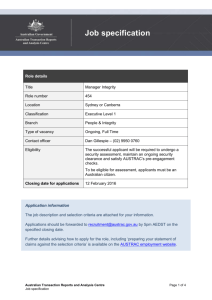

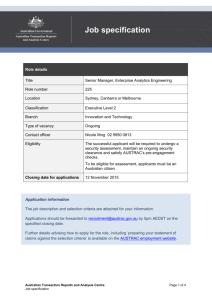

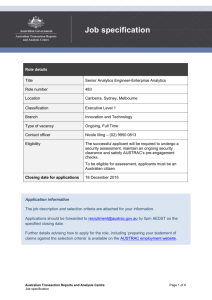

advertisement