CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS: THEORY AND

advertisement

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS:

THEORY AND UTILITY

by

JAMES WILSON PATTILLO, B.S. in C.

A THESIS

IN

ACCOUNTINa

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty

of Texas Technological College

in Partial Fulfillment of

the Requirements of

the Degree of

MASTER OP BUSINESS AMINISTRATION

August, 1959

VV-.

I am deeply indebted to Professor Reginald Rushing

for his direction of this thesis and to the other members of ray committee. Professors P. W, Norwood, and

W, G. Cain, and to Professor A. T. Roberts, for their

guidance and helpful criticism.

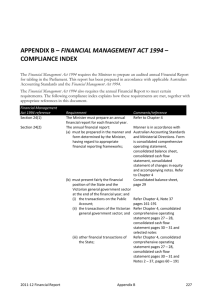

TABLE OP CONTENTS

I*

INTRODUCTION

6

General Observations . . • . . • • • • • • •

Group Financial Statements

10

Statement of the Problem

13

Scope of the Study

ll}.

Limitations

• .

Basic Premises and Assumptions

Terminology and Concepts • •

16

19

23

2l\.

2l\.

25

Consolidation

Merger

Amalgamation • , •

•...••

Combination

Parent, Subsidiary, and Control . . . .

Affiliated Company

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND OF CONSOLIDATED

STATEMENTS

Historical Background of the Holding

26

26

2?

2?

27

26

38

Company in the United States

Histoid of the Consolidated Statement

15

15

Essential Business Entity of the

Holding Company Group

The Auxiliary Nature of Consolidated

Statements • • *

• •

The Primacy of Proper Asset Valuation •

Adherence to the Concept of a Going

Concern

The Desirability of Consistency . • . ,

II.

6

38

...

l\.l

Quantitative Importance of the Holding

Company in the United States

III.

CONDITIONS UNDERLYING CONSOLIDATION

Percentage of Stock Ownership and Control

as a Standard

-3,

l\.7

50

52

k

IV,

similarity of Operations as a Standard . . .

60

National Concentration as a Standard . . . .

63

Consistency of Treatment as a Standard . . .

77

Necessity for Disclosure of Basis of

Incltxsion or Exclusion • . • • » • • • •

STANDARDS UNDERLYING INTERCOMPANY OPERATING

TRANSACTIONS

•

8l

85

A Characteristic Feature of

Consolidation—Elimination

85

Transactions Involving the Debtor-Creditor

Relationship

• • . * .

87

Intercompany Receivables and Payables .

Long-term Loans Among Affiliates • . , .

Long-term Bonds Among Affiliates . . • .

Holdings of Preferred Stocks by

iiX X Xx3>a bes . • • • • • • • • • • « «

Transactions Involving Intercompany

Merchandising or Accommodating

Activities

Intercompany Sales and Purchases of

Goods

Fixed Assets Bought and Sold Among

Affiliates

Other Intercompany Transactions and

Considerations

88

89

90

y(

99

99

120

122

Reciprocal Revenue and Expense Accounts. 123

Contingent Liabilities for Debts of

Affiliates

125

Intercompany Bad Debts . ,

127

V.

STANDARDS UNDERLYING INTERCOMPAl^ FINANCIAL

TRANSACTIONS

129

Investments in Affiliates on Owner's Books . 129

Methods of Carrying the Investment:

Arguments of Each

Treatment of Changes in Equity Due to

Subsidiary's Actions

I30

lb,l

5

Treatment of Changes in Equity Due to

Parent's Actions

ll).9

Intercompany Shareholdings--Eliminations . . 15kVI.

MINORITY INTERESTS AND CONSOLIDATED SURPLUS . .

Minority Interests

....

Allocation of Consolidated Profit

or Loss

Allocation of Consolidated Capital . . .

Consolidated Surplus

VII.

VIII.

163

163

166

168

, 169

CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS' UTILITY PROIi VARIED

VIEWPOINTS

172

From the Viewpoint of the Accoimtant . . . .

172

From the Viewpoint of Management

176

From the Viewpoint of the Investors

....

179

From the Viewpoint of the Creditors

....

I83

SUMr4ARY AND CONCLUSIONS

I87

Siaramary

I87

Conclusions

195

BIBLIOGRAPHY

199

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

General Observations

In an address that was delivered before the Rutgers

University Graduate Seminar in S.E.C, Accounting in 19i|.l,

William W. Wemtz, then Chief Accountant of the Securities

and Exchange Commission, spoke on the subject of consolidated statements in part as followsj

Consolidation accounting is one of the areas in

which recognized principles are few, divergent

principles many, and underdeveloped sectors large.

This kind of accounting and this kind of statement

are discussed in nearly all textbooks; certain elements are the subject of rules by governmental

bodies and the New York Stock Exchange; a few articles have been written, and the professional societies have sponsored a few principles. But for the

most part, these writings stick to a pretty well

beaten path and rarely discuss more than a handful

of questions. Published financial statements likewise scarcely ever disclose any difficult problems

which frequently, if not customarily, arise in

their preparations. . . .

The available discussions of general principles,

the landmarks, are seldom sufficiently detailed to

enable one to determine with reasonable assurance

which of several possible„solutions would be consistent with the premise.

1

See William Herbert Childs, Consolidated Financial

Statements! Principles and Procedures, Cornell University

i-ress Uthaca, New York, 19i4-9;, p. vll. Hereafter cited as

Childs, Consolidated Statements.

2

Childs, Consolidated Statements, footnote No. 1 on

page vii reads as followsz "Wemtz, William W., 'Consolidated and Combined Statements,' an address delivered before

the Rutgers University Graduate Seminar in S.E.C. Accountin;^,

October 5, 191+1 (unpublished), p. 1."

^

Along the same lines, Maurice Moonitz stated in 19i|i4.:

Ttie recent. . .interest in consolidated statements

has emphasized anew the lack of a firm theoretical

foundation on which to build satisfactory multicompany reports. The confusing array of alternative

and sometimes contradictory procedures found in

accounting literature is one Important manifestation of the absence of a generally accepted explanation of the nature, purpose, and limitations

of consolidated statements.-^

Although these statements were made more than fifteen

years ago, they largely hold true today.

There has been no

thorough exploration in the field of consolidation accounting

and consolidated statements as there has been in other fields,

such as cost accounting,

©lis lack of exploration may ac-

count for the absence of generally accepted principles.

As

Mr, Wemtz states, this kind of accounting and this kind of

statement are discussed in nearly all textbooks, and a few

books appear which exclusively treat the subject.

However,

the stress is not on the theory underlying the subject;

-_

rather the emphasis is on the mechanical aspects involved.

Articles have appeared in accounting and other business

Journals; but, here again, the treatment is upon the mechanical phases, or upon isolated problems, with the result that

the theory is either neglected or ciirsorily treated in the

process.

It is generally true, as Mr. Wemtz states, that

3

Maurice Moonitz, Ttie Entity Theory of Consolidated

Statements, The Foundation Press, Inc. (Brooklyn, 1951)>

p. V, Hereafter cited as Moonitz, Entity Theory.

8

"• . .for the most part, these writings stick to a pretty

well beaten path and rarely discuss more than a handful of

questions.**

Recognizing the lack of and need for generally accepted standards underlying the presentation of consolidated

statements, the American Accounting Association has sponsored

research upon the subject, and in 1951^-* the Committee on

Accounting Concepts and Standards published its Supplementary

5

Statement No, 7, entitled "Consolidated Financial Statements."

Also, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

is currently considering in its Committee on Accounting Procedure the desirability of a bulletin on consolidation prac6

tices.

When one considers the nature of the subject itself,

it is somewhat understandable that generally accepted principles have not been formulated.

Consolidation accounting is

a complex subject; its principles are formulated only with

great difficulty.

The principal reason for this difficulty

See the quotation by Mr. Wemtz on page 6.

5

American Accounting Association--Committee on Accounting Concepts and Standards, "Consolidated Financial

Statements" (Supplementary Statement No. 7), Accounting and

^epor'ting Standards for Corporate Financial Statements and

i>^^PP4-e^^ents, American Accountinp; Association (Columbus, Ohio,

iVi?Y), pp. 42-14.5. Hereafter cited as American Accounting

Association, "Consolidated Financial Statements."

6

This is the gist of a parenthetical note appearing

after a related article in the The Journal of Accountancy,

August, 1957. p. 36.

9

is that the formulation of principles entails going beyond

the accountant's concepts of legal equities in the assets of

a single corporation to determine the proper allocation of

constructive equities in the combined assets of a multicorporate enterprise.

Frequently that enterprise is inexactly

termed an "economic entity."

However, the accountant's idea

of an economic entity is usually in terms of his concepts of

the "legal entity."

Thus, the accoimtant is prone to hold

the position of the parent company as a legal entity while he

reaches out to bring in such group data as he can fit into

the pattern of the individual accounts of the parent.

This

idea of legal entity occurs despite the consolidated statement usually being purported to be an exhibit, without regard

for legal boundaries, of the financial and operational data

of a group of affiliated companies.

Therefore, consolidated

statements are frequently devised as expansions of the parent

company data, rather than in accordance with the concept that

the consolidated acco^lnts are those of different business

units; in other words, are frequently?- devised as a legal

entity rather than an economic entity.

As a consequence, once the accountant has formulated

his "principles" of consolidated statements, whether they be

in accordance with the legal or economic entity concept, he is

likely to be hesitant (or even prejudiced) to consider the

other point of view.

In addition to this undesirable condi-

tion, the accountant must submit reports and statements which

10

meet the requirements of various regulatory agencies.

Such

regulatory rules are usually followed blindly, with few

searching questions concerning their theoretical rightness

being introduced.

7

But to say that there are few questions

does not mean that the policies are not sound.

Backing the

soundness of the rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Victor H, Stempf writess

While the requirements of the commission concerning consolidated statements are exacting, and may be

thought by some to exceed reasonable limits in the

volume of data required, the underlying principles

are indisputably sound and provide adequately for

Judgement and flexibility in the presentation of g

material facts as they appear in individual cases.

Nevertheless, such apparent rigidity seems to be unfortunate in any field since progress depends upon the

willingness of the members of the profession to objectively

consider different concepts.

Group Financial Statements

"A group financial statement is an acco\mting device

for presenting in a single report the combined financial

position or the combined operating results of affiliated

7

Childs, Consolidated Statements, pp. vli-ix.

Victor H. Stempf, "Consolidated Financial Statements, " ^_2ie_J[oumal_£f_Ac£^

LXII (November, 1936),

p. 375.

11

9

companies."

It must be remembered that the object of accounts

is to show facts, and that any form of statement which discloses all material facts is equally permissible and proper;

the precise form is largely a matter of circumstances and

10

preference,

A legal entity the structure of which has

branches or divisions or departments must include in its reports the operations of all its constituent parts; the individual accounts of a department or division would be inadequate to give a complete view of the position and operations

of the enterprise.

On the other hand, there is a similar

need for an over-all view when the branches or divisions or

departments are part of the combination of corporations

which are legal entities in themselves.

Group financial

statements provide to interested parties a better view of

theraulticompanystructiire as a whole.

Combined accounts may be presented in one of three

methods:

the combined statement, the consolidating statement,

or the consolidated statement.

A combined statement is a financial statement which is

prepared from the reports of affiliates that are of a different order than that of the controlling company, or are under

9

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 1.

Arthur Lowes Dickinson, "Accounting Practice and

Procedure," in Selected Readings in Accounting and Auditing,

Mary E. Murphy, ed., Prentice-Hall, Inc. (New York, 1952),

pp, 172-173.

12

different conditions.

The combined statement is used in

situations where more and better information could be had by

consolidated statements.

For example, a number of foreign

subsidiaries would issue a combined statement which would be

presented as a supplement to the consolidated statement of

the parent company and its domestic subsidiaries.

The consolidating statement is merely a financial

statement in worksheet form and displays the details that go

into the making of consolidated statements.

This consoli-

dating statement ties together book figures with the published

financial statements, and is occasionally furnished along with

the more foaroial consolidated statements in order to supply

information about the sources of various consolidated items.

"The essential purpose of consolidated statements is

to display the income record and financial position of two or

more associated, but legally separated, companies SLS ±£ they

11

represented a single enterprise."

Through such statements

legal lines are disregarded or at least minimized, and managerial unity is stressed; a picture is drawn of the affiliation—the family of companies--in its over-all relation to

12

the external business community.

In essence, the

11

William A. Paton, and William A. Paton, Jr.,

Corporation Accounts and Statements, Macraillan Company

(New York, 1955), p. 573. Hereafter cited as Pat^n and

Paton, Corporation Accounts.

12

Paton and Paton, Corporation Accounts, p. "73

13

distinguishing characteristic of the consolidated statement

is the presentation, in a single financial report, of the

combined operations and position of the controlling and the

controlled companies.

However, each company must be regarded

13

as a legal entity in itself.

Group statements have a number of common characteristics.

There must be a single control over the policies and

operations of the included companies; moreover, that control

must be exercised, and not merely be potential.

There must

be an economic relation; that is, the companies' operations

must be similar, auxiliary, or complementary in character.

Ownership is also a criterion for combination, as is the

ownership form.

Most significant, however, is that a group

statement does not pretend to present the data as they appear

in the books of account of any individual company.

In this

sense, a group statement is frequently referred to, with substantial basis, as an "artificial" report.

The consolidated statement is the most-used of the

group account forms, and is the subject of this work.

Statement of the Problem

This study will be concerned with the problem of

determining the validity of the following assumptions:

13

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 2,

^ Childs, Consolidated Statements, pp. 1-2.

Ill

(1) that consolidated statements are based on the hypothesis

that underlying legal entities do not exist, and in that

sense, the statements are "artificial"; (2) that the circumstances of presentation and the standards and principles

underlying their preparation are numerous, complex, and sometimes conflicting; (3) that the purposes for which they are

published are few; and (ij.) that an evaluation is needed of

the extent they meet the needs of interested parties.

The objectives are mainly twos

(1) to present and

weigh basic concepts Tinderlying consolidated statements, and

(2) to reach some reasonable conclusions as to the value of

consolidated statements to selected segments of the business

world,

Scope of the Study

Specifically, two broad areas will be covered: (1)

the theory of preparation of consolidated statements, including (a) the circumstances of preparation and (b) the standards

and principles underlying their preparation; (2) the purposes

served or utility, to the accountant, management, investors,

and creditors.

The work deals with the subject of consolidated statements in the following manner:

The institutional background

of consolidated statements is traced in Chapter II; the circumstances of preparation are presented in Chapter III; the

standards and principles underlying their preparation are

15

described in Chapters IV through VI; the value and utility

from various selected viewpoints are covered in Chapter VII;

a summary and conclusions are drawn in Chapter VIII,

Limitations

Because of the vastness of the subject, no consideration will be given to five areas and problems: no emphasis

is placed on the mechanical phases of consolidated statements;

the precise technical form (as opposed to content) that the

statements should take is excluded; the problem of the extent

to which reports submitted to regulatory and other agencies

should agree with the published consolidated statements is

avoided; generally, the practical applications of the theoretical concepts are excluded; and situations involving indirect and reciprocal share ownership relations are excluded.

Basic Premises and Assumptions

It is necessary that the foundation of assumptions be

laid, and these premises will serve to underlie all the subsequent discussion and conclusions.

15

the essential economic lanity

The first two premises,

of the holding company group,

and the auxiliary nattxre of consolidated statements, will be

derived from a discussion on their relation to consolidated

Hereafter referred to as a "business entity" since

"economic unity" has many conflicting connotations.

16

statements,

TUne last three, the primacy of proper asset

valuation, adherence to the concept of a going concern, and

the desirability of consistency, are derived from concepts

16

common to the body of general accounting doctrine.

Essential Business Entity of the Holding Company Group

Consolidated statements are predicated on the assumption that the entire group of companies, legal entities in

17

themselves, form one business and accounting entity.

Ihis view is based upon the historical development of the

holding company-subsidiary relationship and upon the functions performed and powers conferred (^.£., common control)

-j o

by consolidation through share ownership.

It seems that accountants move more quickly to recognize changes in traditional concepts and modes of behavior

than do the courts or legislatures.

But there is a lag

between the changes themselves and their expression in cases

and statutory law.

For example, accountants for years have

treated a partnership as an entity distinct from treatment

of the partners as individuals. However, only recently has

the entity concept been recognized and expressed in the

16

•^ Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 1 2 .

17

John A. Carson, "Accounting for Mergers and Consolidations," The Canadian Chartered Accountant, LXXIV

(April, 1959), p. 327.

16

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 1 2 .

17

Uniform Partnership Act,

The commercial world has similarly treated the single

proprietorship as distinct from its owner, but this concept

has not as yet been given legal effect,

Consistent with this

attitude of a distinct entity are the income tax regulations

in that they treat an individual's business revenues and expenses differently fro™ his personal receipts and outlays.^^

Specifically with reference to corporate combinations

through stock ownership, the law has been hesitant and confusing; as a consequence, a well-settled, consistent body of

legal rules and doctrines is not available to resolve the

accounting problems in the same field.

The authorities are not completely in accord as

to when several corporations will be considered as

a single entity. . . . The rule followed in many

cases is that the legal fiction of distinct corporate existence may be disregarded when a corporation

is so organized and controlled, and its affairs are

so conducted, as to make it merely an instrumentality

or adjunct of another corporation.^*^

19

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 3 .

20

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . [|..

18

There have been a few cases

21

adjudicated in which

were expressed opinions which are more consonant with the

assumptions that are made by accountants in preparing consolidated statements.

The most notable of these opinions, in that

it expresses a virtually complete break with the concept of

the separateness of each corporate entity, was the Judg3ment

in the case that had involved the rights of creditors of a

subsidiary in the assets of the parent. Consolidated Rock

Products Co, V du Bois /5l2 U.S, 510, 61 S,Ct. 675 (19l4.1i7.

There has been a unified operation of those several

properties by Consolidated pursuant to the operating

agreement. That operation not only resulted in extensive commingling of assets. All management functions of the several companies were assumed by Consolidated. The subsidiaries abdicated. Consolidated

operated them as mere departments of its own business.

Not even the formalities of separate corporate organizations were observed, except in minor particulars

such as the maintenance of certain separate accounts.

In view of these facts. Consolidated is in no position to claim that the assets are insulated from

such claims of creditors of the subsidiaries. . . .

A holding company which assumes to treat the properties of its subsidiaries as its own cannot take the

benefits of direct management without the burdens.^^

21

Among the more notable are those cited by Moonitz

(Entity Theory): Robothman v. Prudential Insurance Company,

^k *l.»).Eq. 6V5, 53 Alt. 614.2 (1903); U.S. v. Reading Company,

253 U.S. 26, l|.0 S.Ct. 1^.25 (1920); Hart Steel Company v.

Railroad Supply Company, 2kk U.S. 291+, 37 S.Ct. 506 (1917)}

Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway Company v. Ninneapolis Civic and Commerce Association, 21^7 U.S. i;90, 38 S.Ct.

553 (1918); Industrial Research Corporation v. General Motors

Corporation, 29 F.2d 623, D.C. Ohio (1928).

22

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p p . 5 - 6 .

19

Therefore, there has been limited legal recognition of

the essential business entity regarding combinations affiliated

by stock ownership rather than by merger.

The tendency is for

recognition only in special situations and under certain circumstances, and is not a rule or doctrine applicable to the

23

ordinary transactions of a going concern.

Consequently,

the preparation of consolidated statements is predicated upon

the assumption that the consolidation is an entity in itself,

ISiis entity, however, is almost wholly, though not entirely,

outside the scope of complete legal recognition.

Therefore,

consolidated statements need special Justification, a condition not required of the statements of a single corporation.

The Auxiliary Nature of Consolidated Statements

Because of the limited status, in the eyes of the law,

of the entities to which they refer, consolidated statements

must be regarded as auxiliary.

•:vi;

t-'

They are special-purpose re-

ports; they are not primary, all-purpose exhibits supplanting

23

For example, in Cintas v. American Car and Foundry

Company /12>1 N.J.Eq. 4l9, 2S A.2d i|.l8 {l^k^Y/, the court held

that prior cases dealt with special points and are therefore

not binding in a dispute concerning the status of intercompany

dividends declared and paid in the ordinary course of business.

(See Moonitz, Entity Theory, p, 6.) For analysis of the consolidation accounting implications of this case, see George

0, May, "The American Car and Foundry Decision," The Journal

of Acco\mtancy, LXXIV (December, 191+2), pp. 517-522, and also

the following editorial: "Consolidated and Separate Statements," The Journal of Accountancy, LXXIV (October, 19^2),

P. 293.

20

o\

or displaying the statements of legally recognized entities.

•Rie leading principle of the technique of preparing a

consolidated statement, viz, the elimination of all evidences

of intercompany relationship, requires a shift in viewpoint

from a legal concept—that of a business corporation—to an

accounting concept--that of the business entity.

25

This

method of financial reporting was appropriately described by

M, B, Daniels:

A consolidated statement is a synthetic statement

or accounting device, and a legal fiction. It is the

statement of no single corporation but an amalgamated

statement giving accounting data of two or more separate corporations. Indeed, the final Justification

of the device must rest on the reality of the group

as a single economic and administrative enterprise

despite the existence of the separate legal entities

involved.

Therefore, because of the general lack of recognition

and inadequate comprehension of the essential business entity

of a combination through stock ownership, the courts have not

generally accepted consolidated statements as replacements of

the separate legal-entity reports.

Their status remains that

of a supplement to, but not a substitute for, the statements

2k

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 6,

25

Gertrude Mulcahy, " C o n s o l i d a t e d S t a t e m e n t s - - P r i n c i p l e s and P r o c e d u r e s , " The Canadian C h a r t e r e d Accountant.

LXIX (August, 1 9 5 6 ) , p , 152,

——

of.

Mortimer B. D a n i e l s , F i n a n c i a l S t a t e m e n t s , American

Accounting A s s o c i a t i o n ( C h i c a g o , 1 9 3 9 ) , p . ^^»

21

of the individual corporate units.

Consolidated statements

should not be presented in isolation from the individual

27

reports of a parent company and its major subsidiaries.

•Riis view is in harmony with the statement by Eric L. Kohleri

Combined financial statements portray the Joint

position or operating results of two or more business

or other units as though but one existed. They are

secondary rather than primary in character, and, as

enlargements of the financial statements of a common

controlling interest, they assist in explaining the 28

relationships of that interest to the outside world.

Should the principal legal unit become the combination

as a whole, this premise would be revised; at that time consolidated statements will become primary in character, and the

statements of constituent units will be relegated to the status

29

analagous to departmental operating statements.

Until this

legal transition takes place, the position of the consolidated

statement should remain secondary.

At the present, the use of the consolidated statement

has progressed so rapidly that many regard the statement as

the prime medium of financial reporting by holding companies;

an increasing number of companies include only these statements

27

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 10.

E r i c L. Kohler, "Some Tentative P r o p o s i t i o n s Underl y i n g Corporate R e p o r t s , " The Ac covin t i n g Review, XIII (March,

1938, p . 6 3 . H e r e a f t e r c i t e d as Kohler7 "Tentative Propositions."

29

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 10.

22

in their published annual reports,

Childs supports this

development:

The majority of published statements of companies

listed on the New York Stock Exchange are consolidated statements. They have come to be looked upon

by stockholders and bondholders of a parent company

as substitutes for the legal entity statements of

that company and are usuall^Qthe only accounts provided in its annual report,-'

In further evidence that the concept of a business entity is

gaining in popularity, the state of California by statute has

placed the consolidated balance sheet on a plane of full

31

equality with the balance sheet of the parent company.

It must be emphasized, however, that this statute adheres to

the concept of a supplement, rather than that of a substitute.

In addition to the example of California, formal legal status

has been achieved in Canada by the Companies Act of 1931!-,

which sanctions the publishing of consolidated stat*3ments

without the statements of the constituent companies accora32

panying them.

Nevertheless, until the consolidated statements are

generally legally recognized as substitutes for the separate

30

Childs, Consolidated Statements, pp, 2-3•

31

Rufus Wixon, editor, "Consolidated Statements,"

Accountant's Handbook, The Ronald Press Company (New York,

1956), l4.th ed., chap. 23, p. 5.

Gertrude Mulcahy, "Consolidated Statements--Principles and Procedures," p. 152,

23

legal-entity reports, they should not be used as such, but

rather should be utilized as secondary to the separate parent

and subsidiary statements.

In the light of this basic premise, that of the consolidated statement's auxiliary status, the question arises:

to what groups or interests will consolidated statements prove

most useful?

This question is the subject matter of Chapter

VII,

The Primacy of Proper Asset Valuation

Hie premise of proper asset valuation primacy is derived from the basic attributes of the fundamental accounting

process.

The value of the proprietary equity is equal to the

difference between the values that are assigned to assets and

the values that are assigned to liabilities.

The principal

variable in this case is the value of the total assets.

"This

underlying conception of the whole process of rational bookkeeping is merely a formal reflection of the fact that an

enterprise derives value for its owners through actual and

prospective favorable changes in assets under its control,"

33

The principal problem then is one of the determination

of appropriate values for assets.

Once these values are de-

termined, the size of owner equity is determined by deducting

the amount of creditor clains.

/ further problem is that

•33

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p , 17.

21+

of assigning the charges to the proper accounting period and

to the several ownership interests.

The application of this premise to specific consolidation problems is taken up in a later discussion of controlling and minority interests—as equals in status.

It may be

pointed out here that the assets must not be used as balancing figures to affect values which already have been assigned

to equities.

Adherence to the Concept of a Going Concern

The going concern concept does not require extended

comment since it is an integral part of accotanting and is

generally understood.

The situations in the discussion of

consolidation involve those companies which are not in the

process of dissolution or liquidation.

A combination is pre-

sumed to continue into the indefinite future as a functioning

entity.

Therefore, the special problems which surround liqui-

dation or reorganization of a combination are excluded.

35

The Desirability of Consistency

Consistency of treatment from period to period is

desirable as a means of obtaining statistical c^riparability.

In this regard, reliance is placed on certain objective rules

^

Moonitz, Entity Theory, pp. 17-16.

35

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, pp. 18-19.

25

and standards which will serve to mai:e accounting proced\ires

coherent over the periods.

But this reliance must not become

so rigid as to oppose any necessary alterations.

Alterations

must be made if conditions appear to have changed, and more

proper accounting may be obtained under the alteration.

The

argijment may be advanced that this alteration, of itself, does

not violate the premise of consistency, for the conditions

upon which the prior treatment were based have changed, and

consistency in relation to the previous treatment ends with

the change; a new treatment will now be consistently followed

36

over the periods under the changed conditions.

Terminology and Concepts

At the outset of a discussion of this kind, it is

necessary to define the terms which will be used.

Also it is

necessary, in this case, to distinguish between differing concepts of the same subject.

A basic goal in defining many of the following terms is

to attach specific meanings to words often used interchangeably.

For example, because it has many other connotations, "consolidation" is a poor word to describe the process of preparing

consolidated statements. Many similar problems, which will be

clarified in the present section, exist.

36

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 19.

26

Consolidation

A consolidation takes place when the properties and

debts of two or more corporations are taken over by a new

corporation that is organized for the purpose of acquisition,

and the selling corporations thereafter cease to exist.

The process of preparing consoiiaated statements is

also often referred to as "consolidation."

For lack of a

more accurate term, "consolidation" will be used in this work

according to this latter definition; namely, the preparation

of consolidated financial statements from the individual

financial statements of the affiliated companies.

Merger

By a merger is meant the transfer of the assets of one

or more corporations to another corporation, whereby the

latter corporation, a single legal entity containing within

itself the corporate life of all its constituents, remains as

.,

38

the single and sole owner of the combined assets.

A merger

differs from a consolidation (in the first sense, as stated

above) in that in a merger no new concern is created, whereas

in a consolidation a new entity acquires the net assets of

37

Homer V. Cherrington, Business Organization and

Finance, The Ronald Press Company (New York7 19.'i-b), p. ' ^ 0 .

38

James C. Bonbright, and Gardiner C. Means, Holding

Companies; its Public Significance and its Regulation,

McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. (New York, 1933), p. 27.

27

the combining units.

Amalgamation

An amalgamation is a combination under a single head

of all or a portion of the assets and liabilities of two or

^ .

39

more business iinits by merger or consolidation.

The word

"amalgamation" is preferred by some as a synonym for consolldation and not for merger.

Combination

The terra "combination" as used in this work will

designate a method of external expansion of business by which

conjoined corporations retain their positions as sepsu^ate

legal entities.

Parent, Subsidiary, and Control

A "parent" is a corporation which is in a position,

however attained, to direct or cause the direction of the

corporate affairs and operations, or only the operations, of

another corporation,

A "holding company" is commonly termed

a "parent" and the two terms are considered to be synonymous.

39

Eric L, Kohler, A Dictionary for Accountants,

Prentice-Hall, Inc, (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 195o),

2nd e d . , p . 3 0 .

ijo

,

C h e r r i n g t o n , B u s i n e s s O r g a n i z a t i o n and F i n a n c e , p . J!20.

Childs, Consolidated Statements, footnote no. 1, p . 3 .

28

A "subsidiary* is a corporation whose corporate affairs

and operations m a y be directed, or whose operations may be

k2

directed only, by another corporation,

"Control" (including the terms "controlling" and

"controlled b y " ) as used herein, means the possession,

directly or indirectly, of the power to direct or cause the

direction of the management and policies of a corporation,

however it is attained.

In some cases there may exist a

Joint control by two or more entities of a corporation; this

Joint control is termed a "community of interest," and is not

a parent-subsidiary relationship since no one company is in

the dominating position.

Affiliated Company

An affiliate or affiliated company is a corporation or

other organization related to another by owning or being owned,

i|5

by common management, or any other control device.

Or,

parent and subsidiaries, or subsidiary companies, taken together, are termed "affiliates"; that i s , any separate entity

ii6

of the group is an "affiliate."

^

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. i|.

k-3

Edward A. Kracke, "Consolidated Financial Statements,"

The Journal of Accountancy, LXVI (December, 1 9 3 8 ) , p. 376.

^^ Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 5.

k5

Kohler, A Dictionary for Accountants, p. 26.

I4.6

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. k>

29

Various Affiliating Devices.

The usual method of

forming and maintaining a parent-subsidiary relationship is

the acquisition and retention by one company of a controlling

interest in the voting stock of another; that is, a control

device commonly used is intercorporate stock ownership. From

a practical point of view, such action may be equivalent to

a merger or consolidation since properties are now under

unified management and control; legally, however, a separate-

^ ^

k7

ness of identities remain

regardless of the corporate con-

trol that may be exercised.

Ordinarily the state laws do not forbid this type of

affiliation; they may specifically permit the organization of

companies for the sole purpose of acquiring and holding the

k9

stock of other corporations.

The distinction Is sometimes

made between a "pure" and the "operating holding company."

The sole business of the former is the ownership of controlling interests for the purpose of control (as opposed to

investment only) of stocks of other companies.

The latter

'^ Howard S. Noble, Wilbert E. Karrenbrock, and Harry

Simons, Advanced Accounting, South-We stern Publishing Company,

Inc. (Cincinnati, 191]-1), p. 562.

li.8

See the case of Majestic Co. v. Orpheum Circuit,

Inc. (21 F.2d 720) for the legal conception of the separateness of the corporation and its stockholders and those circmistances that may call for a denial of such separateness.

k9

Wilbert E. Karrenbrock and Harry Simons, Advanced

Accounting--Comprehensive Volume, South-Western Publishing

uompany. Inc. (Cincinnati, 1955), 2nd ed., p. 319.

30

usually manages subsidiaries as adjuncts to its own business,

Since intercorporate stock ownership is the usual

affiliating device, a parent is usually a holding company.

Purtheinnore, it is generally assumed that a holding company

is in a position to iirect both the corporate pblicies and

the operations of a subsidiary.

The control is usually in50

direct through parent-appointed directors and officers.

^ ® co3:'P0i*ate lease is another method of establishing

a parent-subsidiary relationship.

This method of obtaining

control, however, relates to the use of the physical proper-

51

ties rather than to the management of corporate policies;

that is, the transfer of property under lease presumes no

necessary intervention by the lessee parent in the corporate

policies of the lessor subsidiary.

Therefore, under this

method, one corporation may lease for a period of years

(999 years not being uncommon) the entire property of one or

more other corporations.

Thus, while the parent manages its subsidiary's properties (i.e., directs the operations), a function which the

subsidiary would do in the absence of a lease, the corporate

organization of the subsidiary remains untouched by outside

interference.

This arrangement is contrasted to holdinT

50

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. o.

51

William T, Stmley and William J, Carter, Corporation Accoimting, The Ronald Pr^ss Company (New York, l^il"),

revised ed,, pT 288,

31

company control, in which the parent dominates both the

operations and the policies of the subsidiary.^^

Still another way of effecting a parent-subsidiary

relationship is by means of the management contract.

Such

a contract usually provides that a "service corporation"

(the parent) undertake the management of an operating company (the subsidiary).

The service corporation may furnish

engineering, financing, accounting, and general supervisory

services.

Through this device, the scope of the combination may

be expanded with little or no additional investment of

capital.

"Here, again, when the contract is the sole con-

Joining factor, the parent has the right to direct the operations only; the subsidiary retains its independence in the

^ 53

conduct of its corporate affairs 22'£*' policie^7"

The three most important affiliating devices have

been briefly described above.

The principal point of differ-

ence between them is in the respective rights of the parent

to dominate the strictly corporate policies or affairs of

the subsidiary.

Concerning the direction of operations,

however, much the same result is had under the three methods.

Outside control is present under each case.

Since the acquisition and retention of a oontrollin:;

52

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 9.

53

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 9.

32

interest in the stock of one corporation by another is the

usual affiliating device, that type is the most important

one for the purpose of this study.

The consolidated state-

ment has as its purpose the showing of the financial position

and operating results of two or more affiliated enterprises

as they would appear if they were one organization.

There-

fore, the control over operations or corporate policies of a

subsidiary may have an important bearing upon the decision

to include or exclude it from the group presented in the con-

?k

solidated statement.

Such situations will be discussed in

Chapter III,

Relationship Concepts of Affiliation.

An Accountant

usually holds one of two basic attitudes toward the affiliate

relationship.

Whichever concept is held will affect the

parent company's accounting procedures and the consolidated

statement.

Inasmuch as the consolidated statements will be

affected by the method employed, a brief discussion of the

two concepts follows:

5S

As discussed above,

the courts are slow and reluctant

to recognize the concept of a group entity, or business entity,

upon which accountants have frequently based the consolidated

9x

Cf. the discussion of leased and contracted subsidiaries as ^ i n g "uncontrolled" in Kohler, "Tentative Propositions," p. 6Ij..

So

See the section "Auxiliary Nature of Consolidated

Statements," page 19,

33

report.

The courts appear to believe that great harm would

be done if the corporate entity were to be treated with

flexibility in consolidation.

Thus, consistent with the

legal-entity concept at law is the "cost method" of valuing

the investment account on the parent's books, and this is

unadjusted unless, for conservatism, it appears that a perma-

. ^

56

nent decline in value has taken place.

Likewise, an affil-

iate may realize an immediate profit on a transaction with

another affiliate or in an affiliate's securities.

And the

earnings of a subsidiary do not accrue to a parent \mtil

57

dividends from those earnings have been declared.

These

topics will receive more extended attention in later chapters

According to the legal-entity concept, the consolidated statements should show the combined accounts of a

"central-financial interest."

This interest is composed of

the stockholders of a holdin^r company who, through c iTnership

of the parent company, may be said to constructively own the

subsidiaries also.

According to this view, the consolidated

statement is regarded as an expanded parent compmy report

and as a substitute for the parent's statement.

For the

56

H. A. Finney and Herbert E. Miller, Principles of

Ac counting;--Advanced, Prentice-Hall, Inc. (New York, 1952),

i|.th ed., p, 3k-3t and H. A. Finney, Principles of AccountingAdvanced, Prentice-Hall, Inc. (New Yorl:, 191i6j, 3rd ed., p.

^99. THe former will be hereafter oited as '^inney ind Miller

Advanced Accovmting, 14-th ed., and the latter as Finney,

ACvaneed Accounting, 3rd ed.

"^7

" Childs, Consolidated Statements, pp. [L7-1'.8.

i

3k

purpose of minimum ambiguity in terms, the concept which

stresses ownership as the area of the entity, the legal entity

concept or "control financial interest," will be renamed the

58

"financial-'unit" point of view.

A proponent of the second concept (that of a "business

entity") holds that the peculiar relationship existing among

affiliates gives rise to the necessity for special handling

of intercompany transactions on the books of both com-panies

involved.

This view is accompanied by the suspicion that

intercompany transactions are not likely to be at arra's

length.

This concept of the business entity, like the finan-

cial-unit concept, takes the position that, theoretically,

the consolidated statements should reflect the effects of

all the affiliate's transactions as though they were in fact

those of one company.

According to the second concept, the purpose of consolidated statements is to present the assets, equities, and

earnings of the business entity.

That is, the statements

display the combined financial and operating data of all the

affiliates which cooperatively produces goods or services.

This philosophy is not concerned with whether or not the consolidated proprietorship presents the stockholders' equities

of one or several interests; rather, it is concerned with the

presentation of relationships which have no legal status, and

58

Childs, Consolidated Statements, pp,

kl'SO,

35

is likely to be misleading if it shows signs of adhering

closely to the pattern of accounts of a particular legal

entity (the parent company).

59

Therefore, consistent with

this concept is the "equity" or "book value" method of

valuing the investment account on the parent's books; the

investment is recorded at acquisition at cost, but is adJusted for earnings and dividends and losses of the subsid60

iary as those events occur.

According to the business entity concept, the consolidated statement is regarded as secondary and axixiliary to

the affiliated companies' reports.

Again, for the purpose

of minimum ambiguity in terms, the concept which stresses

operations as the area of the entity, the "business entity,"

61

will be renamed the "operational-unit" point of view.

As was noted before, whichever concept is followed

will affect the consolidated statements of the business

entity.

Specifically, the effect will be upon the treatment

of minority interests and upon the inclusion and exclusion

of affiliates in consolidation.

Ihe concepts in relation to

these two topics will be discussed in later chapters.

The foregoing discussion was predicated on the

59

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. [|-7.

60

Finney, Advanced Accounting, 3rd ed., pp. 297-299,

and Finney and Miller, Advanced Accounting, [|.th ed., p. 3I4.3.

61

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 50.

36

assumption that the consolidated statement is a report that

combines the position and activities of two or more corporations which are affiliated but are of themselves separate

entities.

That is, the statement is prepared as if it rep-

resented the position and activities of a single business

entity.

That the group of companies constitute a single

business entity, however, is not the only theory that has

been advanced.

For example, the fund theory is applied to

consolidated reports in the following statement:

The fund theory viewpoint is something of an extension of entity theory, to embrace a less personalis tic set of ideas, and to emphasize even more

the "statistical" viewpoint in dealing with accounting problems, XJnier fund theory, the basis of accounting is neither a proprietor nor a corporation.

The area of interest covered by a set of acco\mts

is independent of legal patterns of organization.

The accounting-unit-area is defined in terms of a

group of assets and a set of activities or functions for which these assets are employed. Such

a group of assets is called a f\ind.

A partial use of this conception obviously underlies accounting for a sinking fund in ordinary financial reporting. The fund concept is less obvious, but

nonetheless relevant to the notions that lie behind

the preparation of consolidated financial reports.

Strict /legal/ entity theory is too closely related

to the legal""concept of a corporation to fit an organization comprising a number of corporate units.

The notion of a fund which encompasses all of the

assets and activities of a group of corporations

is, however, a perfectly reasonable approach to

consolidated statements.°2

62

William J. Vatter, "Corporate Stock Equities, in

Handbook of Modem Accounting Theory, Morton Backer, ed.,

Prentice-Hall, Inc. (New York, 1955), p. 367. Hereafter

cited as Vatter, Modem Accounting Theory.

37

Similarly, Moonitz points out the possibility of applying

the partnership theory:

The partnership concept may possibly be invoked

as a basis on which to construct consolidated statements. This alternative may assume two forms: first,

the statements are based upon a presumed partnership

of corporations, or second, they reflect a presumed

partnership of controlling and outside interests.

The first fonn assumes that the constituent companies

are on a plane of rough equality, an assumption not

consistent with the actual functioning of a holding

company group. Fundamentally the same objection may

be made to the second form. No partnership in any

but the most strained sense exists between controlling and outside interests. True, a minority interest in a subsidiary has rights which must be

respected but this consideration acts merely as

a limit to the freedom of action of the controlling group. Ihe minority may not act Independently

or exercise veto power over business policy determined

by a controlling interest,^3

These alternative concepts will not be analyzed; an

extensive analysis would be possible, and probably enlightening, but limitations of time and space necessarily narrow

the discussion to the scope already mentioned.

63

Moonitz, S n t i t y Theory, pp. 16-17.

CHAPTER II

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND OF

CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS

Consolidated statements do not exist in a social

or economic vacuum, Ttiey were developed to fulfill

a real need arising out of specific historical conditions; they are reflections on the accotinting level

of the distinctive pattern assumed in this coiintry

by the combination movement. When those historical

conditions alter sufficiently, consolidated statements will be supplanted by forms more congenial

to the changed circumstances.-^

Historical Background of the Holding Company

in the United States

The trend towards combining business undertakings

spread from England to the United States, and increased

rapidly the number and size of industrial combinations from

the late l880's to the depression of 1903. However, the

form was somewhat different from the pattern of consolidation set in Britain.

For the most part, these combinations

were in the trust form of organization in which a board of

trustees assumed ownership of the corporate shares of numerous

2

small competing firms.

"The holding company is an American invention--a

1

Moonitz, Entity Theory, p. 1.

p

Certrude Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies and

Consolidated Financial Statements." The Canadian Chartered

Accountant, LXIX (July, 1956), PP. 59-^0. Hereafter cited

as wuicany, "History of Holding Companies."

38

39

product of the nineteenth century,"

Prior to 1893, however,

the holding company was practically imknown in American financial history.

For many years state legislatxires exclusively

reserved the prerogative of deciding in individual cases

whether corporations should be authorized to buy at will the

stock of other organizations.

And these authorizations were

k

granted only by specific acts to a certain company.

The federal government's national economic policy

followed the theory of laissez-faire, and, therefore, the

giant trusts and monopolies developed without legal restrictions or control,

^ i s development stifled competition and

limited business opportiinities; as a result, the federal

government was forced to intervene and to regulate certain

business practices.

This regulation was accomplished in

1890 by the Sherman Ant1-Trust Act which, in effect, outlawed the use of the trustee method of control.

Stimulus to the control of several corporations by

means of stock ownership was given by the Sherman Act.

The

legal means of evading the Sherman Act were provided in 1893

by New Jersey, when it amplified by amendment its corporation

law that was originally adopted in I888 to permit one

3

Cherrington, Business Organization and Finance,

p, 1+01,

Cherrington, Business Organization and Finance,

p, 1^01.

Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies," p. 60.

i^o

corporation to hold shares in other corporations.

6

Other states followed New Jersey in enacting legislation to permit the holding company form of combination; however, the motive of monopolistic control was not changed.

The form merely changed while the substance behind the form

remained vindisturbed.

This shift from business-trust ani

voting-trust types of combination to the holding-company form

7

did, however, stimulate the growth of the holding company.

In practice, the holding company device proved defective as a means of circumventing the Sherman Act, A 1901;

Supreme Court decision (Northern Securities, 193 U,S, 197)

finally established that, without any doubt, the holding

companies were subject to the anti-monopoly legislations.

Further emphasizing the point, a decision (221 U,S. 1) in

1911 dismembered by court decree the Standard Oil Company,

a holding company.

In 191ij-, the Clayton Act was passed,

amending the Sherman Act to increase its effectiveness.

The

Clayton Act made illegal the acquisition by one organization

of stock in another company engaged in interstate commerce

where the result might be a substantial lessening of compe-

8

tition between the two companies.

"Since the passing of

6

Arthur Stone Dewing, Financial Policy of Corporations,

The Ronald Press Company (New York, 1953), vol. Z, ed. 5, p. 572.

7

Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies," p. iM.

8

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 2 , and Mulcahy,

of Holding Companies, " p . ^^0.

"History

kl

the Clayton Act, the holding company has been used primarily

as a method of combining business enterprises which are

9

largely non-competing:"that is, by the creation of circular

or of vertical combinations.

Except during the depression years of the 1930's, the

period since 191I4. has been characterized by a growth, in the

majority of industries, of the holding company which was

based upon the principles of efficiency of operations rather

than upon the suppression of competition.

Most of the large industrial corporations today are

operating holding companies, thus, the company can operate

its own enterprise and, at the same time, can manage by

corporate ownership of controlling shares, the affiliates

corporation through a board of directors of its own choosing.

History of the Consolidated Statement

The history of the consolidated statement may be

traced through the published reports of corporations, the

literature of acco\inting, and the questions and problems on

CPA examinations.

As might be expected, the consolidated

Mulca;hy, "History of Holding Companies," p. 61.

Moonitz, Entity Theory, p. 2.

Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies," p. 61.

12

Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies," p. 61.

k2

statement was used in practice before the philosophy and

procedures of consolidation were discussed in the literature

13

and examinations treating the subject.

Consolidated statements emerged as an accoiinting byproduct of the development and growth of the combination

movement in the United States and were adopted later in

other parts of the world.

Therefore, the history of the

development of their use in published reports has been

largely the history of the development of the holding company.

There is available some evidence which indicates the

earlier presentation of statments In combined or consolidated

form, but widespread use did not appear until the first decade of the present century.

Ik

Sir Arthur Lowes Dickinson, a senior partner of Price

Waterhouse & Company, was perhaps the most instrumental among

accountants in initiating the movement which led to the general use of consolidated statements by holding company groups

in the United States.

In 1902, Dickinson developed for US

Steel the first consolidated balance sheet that was published

and circulated in the United States.

A precedent being set,

this publication was influential and was followed by many

13

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p . ^ 3 .

^ Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, pp. 6-7.

k3

15

others.

The consistent use of consolidated statements by

US Steel provided a great stimulus to the initial stages of

16

recognition of the value and general use of the statements.

Bie first extended discussion of the consolidated

statement in American business publications was an article

by Dickinson in the first volume ^19067 of The Journal of

17

Accountancy,

in which he took the position that a consolidated statement is necessary for the proper presentation of

the accounts of a holding company.

In the July, 1925 issue of The Journal of Accountancy,

an editorial provided an interesting observation on the early

recognition of the value and use of consolidated statements.

Some years ago It was frequently necessary for

accountants to impress upon clients the value of

a consolidation in financial statements in giving

shareholders in holding companies a general view

of the effective financial condition of the enterprises in which they were investors. The reform

did not meet with immediate acceptance and in

many cases it was a matter of some difficulty to

carry conviction to the minds of clients. Later,

however, such bodies as the New York stock exchange,

the federal reserve board, and the ways and means

15

-^ Percival P, Br\indage, "Consolidated Statements,"

Contemporary Accounting, American Institute of Accountants

(new lork, 19i|.5), chap7 5, p. 1. Hereafter cited as

Brundage, Contemporary Accounting,

Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies," pp. 61-62.

17

Arthus Lowes Dickinson, "Some Problems Relating to

the Accounts of Holding Companies," The Journal of Accountancy, I (April, 1906), pp. I|.87-l|91.

hk

committee of the house of representatives became

appreciative of the value of consolidated accounts

and of the meagreness of the light afforded in

many cases by purely holding company accounts, and

the practice of consolidation extended rapidly so

that to-day the standing of consolldatedQaccounts

in American finance is beyond question,^"

An early textbook. Consolidated Statements for Holding Company and Subsidiaries, by H, A, Finney, was published

19

in 1921^,

This was a work of notable importance and was

followed by G, H, Newlove's Consolidated Balance Sheets

/I9267

and was followed by his Consolidated Statements

^ o^ 21

Including Mergers and Consolidations /19l|.£/.

Now, almost

all accounting textbooks which treat the more advanced subjects have a section dealing with the preparation of consolidated statements.

"Aside from the holding company itself, probably the

most influential factor in shaping the uneven development of

the popularity, the form, and the content of consolidated

18

"Development of Consolidated Statements," The

Journal of Accountancy, XL (July, 1925), p. 39.

19

H, A. Finney, Consolidated Statements for Holding

Companies and Subsidiaries, Prentice-PIall, Inc. (New York,

1924). Hereafter cited as Finney, Consolidated Statements.

20

George Hillis Newlove, Consolidated Balance Sheets,

The Ronald Press Company (New York,192D).

21

George Hillis Newlove, Consolidated Statements

Including Mergers and Consolidations, D. C. Heath and

uompany fNew York, 1914-^), Hereafter cited as Newlove,

Consolidated Statements.

statements has been the various Federal revenue acts."

22

There has been a continuous, but varying, interest in the

technical development of the statement, the interest varying

directly with the extent to which consolidated returns are

23

acceptable for income-tax purposes.

In addition to the Bureau of Internal Revenue, other

public and quasi-public agencies have given partial or complete recognition to consolidated statements. The California

2ll

Corporation Law has already been cited;

the Securities and

Exchange Commission has discretionary power to require consolidated statements ^^ecurities Exchange Act of 19314-, Sec.

13(bJ[7 and prescribes directions in Regulation S-X, Article

kf

for the "consolidated and combined statements" for those

25

electing to use them;

the Stock List Department of the New

York Stock Exchange also provided to the holding companies

the option of publishing separate statements for the parent

and each subsidiary or consolidated statements for the group,

26

with specific requirements laid down for the latter choice.

Regarding the topic of consolidated statements included

22

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 7 . See a l s o Kracke,

" C o n s o l i d a t e d F i n a n c i a l S t a t e m e n t s , " p p . 373-375•

23

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 7 . See a l s o Brundage,

Contemporary A c c o u n t i n g , c h a p . 5 , PP. 2-3*

2h

^ See page 2 2 ,

25

K r a c k e , " C o n s o l i d a t e d F i n a n c i a l S t a t e - i e n t s , " P , 375.

26

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p p . b - 9 .

1+6

in early C,P,A, examinations, Childs states:

The first C P . A , examination found, , ,which

included a problem on the accounts of a holding

company was the June, 1901^., "Practical Accounting"

examination set b y the State of New York. A similar

problem w a s assigned on the Illinois "Practical

Accounting" examination of M a y , 1905, and on the

Pennsylvania "Theory of A c c o u n t s " examination on

the same date. There were also similar problems

in the New York "Auditing" examination of October,

1 9 0 7 , and in the Illinois "Practical Accounting"

examination of 1 9 0 7 ,

A problem on the Illinois "Practical Accounting"

examination of M a y , 1 9 1 2 , was the first found in

w h i c h a consolidated balance sheet was required.

This w a s a very simple o n e , calling for the combination of the accounts of parent and subsidiaries

at date of acquisition. No adjustments and only

two eliminations were required, A more difficult

problem was set on the Illinois "Practical Accounting" examination of M a y , 191ij-, '

Since that time, questions and problems on consolidation procedures and theory have occurred with relative

frequency.

In the light of the brief historical survey presented

above, it appears that the device of consolidated

statements

for presenting group accoimts of affiliated companies has

been used by accountants for almost sixty years.

About

fifty years ago the philosophy and procedures were first

discussed in the literature of accounting; about that time,

also, questions and problems on consolidation were first

27

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 1^6.

k7

included in CPA examinations.

28

Quantitative Importance of the Holding Company

in the United States

The parent-subsidiary organization has a very important place in the American economy,

A study was made in 19i;0

by the Work Projects Administration under the sponsorship of

the Securities and Exchange Commission and showed that 1,114-7

of the 1,961 (58^) registrants studied (out of 2,14.85 with

securities listed on the national securities exchanges on

29

June 30, 1938) had one or more subsidiaries apiece.

Of the above 1,114.7 holding companies, the following

distribution was given:

90 registrants reported no active subsidiaries

675 registrants reported 1 to 5 active subsidiaries

177 registrants reported 6 to 10 active subsidiaries

85 registrants reported 11 to 20 active subsidiaries

l4i4- registrants reported 21 to 30 active subsidiaries

38 registrants reported 3I to 50 active subsidiaries

25 registrants reported 51 to 100 active subsidiaries

13 registrants reported 101 and over active

28

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. I4.6.

29

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 11. The study

was made by the Work Projects Administration of the Securities and Exchange Commission, entitled Statistics of Ancrican Listed Corporations, Part 1 (December, 19U-0).

^8

30

subsidiaries.

The 1,114.7 reported the control of 13,233 subsidiaries in the

31

year 1937, or an average of 11,5 pe3? company

or an average

32

of 10,1 active subsidiaries per registrant.

Except for

the electric light and power industry, the active domestic

subsidiaries were classified as to the number of steps they

were removed from their parent companies, as follows:

70 per cent were one step removed from their parents

23 per cent were two steps removed from their parents

5 per cent were three steps removed from their parents

2 per cent were four or more steps removed from the

33

parent company.

More than four-fifths of the subsidiaries were controlled by

their immediate parents through ownership of at least 95 per

cent of their voting power. More than 20 per cent of all

subsidiaries were incorporated abroad.

3k

From the study, Moonitz concludes that:

30

^,

Newlove, Consolidated Statements, p. 26.

31

Childs, Consolidated Statements, p. 11.

32

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 1 1 .

33

Newlove, Consolidated Statements, p. 26.

3k

Moonitz, E n t i t y Theory, p . 1 1 .

k9

• , ,for the important segment of American business

represented by the Securities and Exchange Commission's summary, (1) the type of intercorporate relationship giving rise to the use of consolidated

statements is prevalent in all sectors of the economy, (2) foreign subsidiaries play a significant

part in the American corporate structure, (3) subholding companies are employed extensively enough

to warrant some attention, and (k) the problem of

outside or minority interest is of strategic importance in about one-fifth of the cases,35

A similar though less exhaustive study was made by

the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, and

published in Accounting Trends and Techniques,

The 1955

edition shows that in 195^, 8l,i|. per cent of the 600 companies included in their annual survey had subsidiaries.

•^6

In the 1957 edition, of the 600 companies surveyed, 510, or

37

85 per cent had subsidiaries.

It is not to be denied that, over the years, the

holding company form of combination has been established as

an integral part of American industrial activities.

35-^ Moonitz, Entity Theory, p. 11.

•^6

Mulcahy, "History of Holding Companies," p. 61.

37

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants,

Accounting Trends and Techniques in Corporate Annual Reports-televenth Fdition, American Institute of Certified Public

Accomitants (New York, 1957), p. 126.

.liuU

CHAPTER III

CONDITIONS UNDERLYING CONSOLIDATION

There has been extended discussion among accountants

about the conditions which should be present to Justify the

1

preparation of consolidated statements.

At the outset of

a discussion of this topic, it may be well to state a general

rule:

", , .when power to control is present, that principle

of inclusion or exclusion should be followed which will most

clearly exhibit the f,inancial condition and results of opera2

tion of the parent company and its subsidiaries."

Generally, the presentation of consolidated statements

is in order when there exists a business entity composed of

3

two or more legally separate units.

And conversely, since

consolidated statements are designed to reflect the position

and operations of a group of closely related business units,

they should not be prepared unless the assumption of a business entity can be Justified.

The general principle is

clear; and, in the majority of cases, its application is

easy.

However, in other situations the principle is far

•^ William A. Paton and Robert L. Dixon, Essentials

of Accounting, The Macmillan Company (New York, 195^5), p. 726.

Carman G. Blough, ed., "Criteria Involved in the

Preparation of Consolidated Statements," The Journal oi

Accountancy, LXXXVIII (November, 19i+9), p. 14-37.

3 Moonitz, Entity Theory, p. 20.

^ Carson, "Accounting for Mergers and Consolidations,"

p, 32Q.

50

51

from easy to apply.

Thus, to make it objective and definite,

the principle must be recast into concrete form,

"The need for explicitly stated objective standards

arises from the wide circulation accorded published consolldated statements,"

When the statements are given general

circulation, their specific frame of reference must either

be known to potential users or clearly expressed in the

statements themselves, otherwise, there is room for misimder6

standing of the data as presented,

7

As was noted above,

the financial-Tmit or operational-

unit concept that is followed will affect the consolidated

statements of the business entity; under consideration here

is the effect upon the inclusion or exclusion of the affiliates in consolidation.

The basic areas of conflict are the

percentage of ownership and the control exercised.

Common

criteria exist, however, among both concepts, and these

criteria include the agreements that only economically related companies be included, and that subsidiaries which

were not to be held for any length of time be excluded, to

name only two.

The presence of the common criteria concern-

ing inclusion or exclusion of a subsidiary appears to indicate

that the two points of view are different only in degree.

-^ Moonitz, Entity Theory, p, 20,

Moonitz, Entity Theory, p. 20.

7

See page 32,

52

and not different in kind; both are trying to show as much

of the data of business entity as their basic philosophies

8

will allow.

Regardless of the choice of concept, niamerous criteria

have been employed for the determination of the area of consolidation.

Attention will be directed to the major criteria,

Percentage of Stock Ownership and Control as Standards

It is obvious that consolidation through stock ownership cannot exist without the concentration of the subsidiary's shares in the hand of the dominant parent company.

As a consequence, a percentage of stock ownership is fre9

quently cited as an appropriate standard to use.

Further-