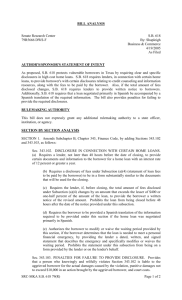

An analytical review of credit risk transfer instruments

advertisement