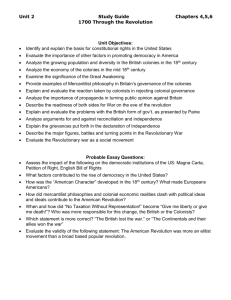

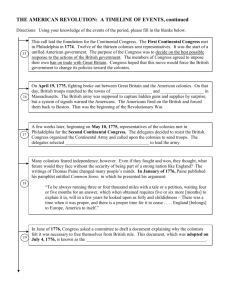

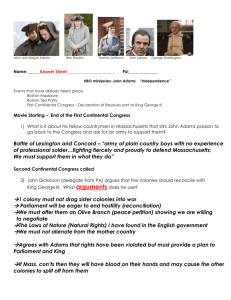

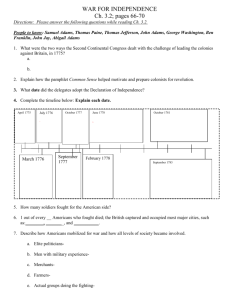

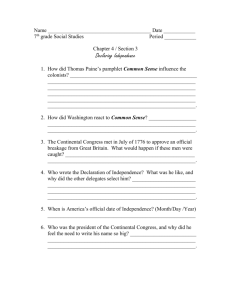

THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE OR THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

advertisement