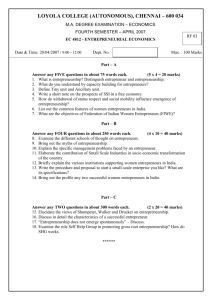

A report on Entrepreneurship - National Knowledge Commission

advertisement