Plot Study

advertisement

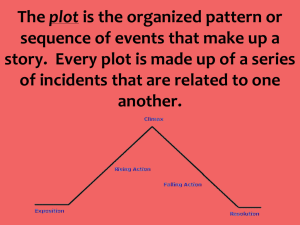

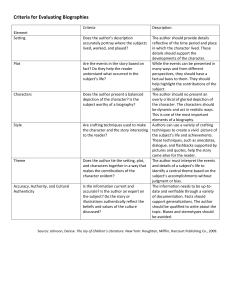

Plot Study and Analysis Perhaps the single most important structural element in narrative fiction is plot, a summary of the rising action in the story, often including the dialogue and action of the principle characters. What precipitates this action? What is the motivating, driving force behind Uncle Tom in his endeavor to live a good life? This force will drive the rising action, involve both the characters and the reader in the conflict, leading up to the climax/crisis, with the falling action leading to the end resolution. To prepare a Plot Study, begin with an introduction to the genre, the type of literature you are writing about. There are main categories which will help identify your selection (although this list is not exhaustive); 1) Tragedy In a tragic narrative, humans do not and cannot overcome inevitable failure, though they may demonstrate courage or grace along the way. Shakespeare’s King lear, Macbeth, and Hamlet, and Sophocles’ Antigone are excellent examples of tragedy. Saul and Samson are examples of tragic figures in the Bible. Their characters have a tragic flaw that dooms them in their lives here on the earth, yet they maintain their relationship with God. The obvious comparison is of the saved verses unsaved tragic characters. 2) Comedy A comic effect is produced when the plot leads the characters into amusing situations, ridiculous complications, and a happy ending. Inciting the reader or audience to laugh at their own imperfect fallen nature by reproducing it in word pictures or on the stage is a gift Shakespeare was genius with. The purpose of comedy is to ridicule vice. We see the character’s suffering, due to his own human limitations, but are able to laugh at him because we are so detached (it isn’t our problem). Comedy can teach us to hold moral faults in contempt. No one gets seriously hurt, no one usually dies. We are able to laugh at Huck Finn’s ignorance because we have no personal concern for his lack of education. We laugh at the antics of Jo’s boys in Little Men because they parody and exaggerate what we have seen and enjoyed in real-life settings. 3) Satire A narrative is satiric when it makes a subject look ridiculous. The subject may be an individual, an institution, government, society, or mankind’s fallen nature, which are parodied or travestied in an effort to make a point. In English Survey we read Swift’s satirical essay, A Modest Proposal, in which the author calmly suggests an end to poverty by the enforced starvation of the poor (then eat them). It should be noted in satire and comedy that making fun of a cherished virtue violates the comic spirit. This is why Christians are ashamed and embarrassed when they unwittingly laugh at a joke ridiculing the sacred. Political cartoons are famous for the satire they portray. 4) Romance Romance was birthed in the Medieval Ages (Arthurian tales, Canterbury Taless). A romance usually makes a clear distinction between the good guys and the bad guys. The plot will be one of adventure, unlikely events, and extreme circumstances, as in the works of Hawthorne, Cooper, Irving, and Melville, where the reader must exercise a willing suspension of belief. Romanticism in America is also referred to as the American Renaissance. 5) Realism A realistic narrative is in contrast to the romantic narrative. Realism mirrors real life, not idealistic, or life as the reader wills it to be. The main characters may not be good or beautiful, noble or admirable. The reader may put down the story feeling unsatisfied. Henry James, Twain, and Walt Whitman each reflect this disappointment after the Civil War. Without the Biblical promises and hope, men are left to find their own answers and trust in science (what man can do for himself, apart from God). Plot Study and Analysis 1 www.thelmaslibrary.com 6) Essay/Sermon/Journal A topic of conversation to discuss or convince, argue, and inform. It often contains a thesis statement. An example is The Federalist Papers. Jonathan Edwards recorded his personal conversion experience and his sermons. Mary Rowlandson recorded the account of her captivity by Indians. 7) Biography or Autobiography The story of a person’s life, such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas. 8) Informational texts This could include Carl Sandburg’s Abraham Lincoln: the War Years. The Puritans and Colonists recorded accounts of their lives and progress in Bradford’s, Of Plymouth Plantation, and John Smith’s, General Historie of Virginia (sic). 9) Fiction Novel, Short story, Tall Tale, Fable, Folktale, Parable, Legend, Epic (Homer, Vergil, Milton). =>The fiction narrative writer may utilize several genre structures and techniques, or literary devices such as flashback, soliloquy, allegory and other figurative language, rhyme, meter, foreshadowing, a stock character, or classical allusions. <= Next, introduce characters and setting (e.g., Tom is a black slave in the pre-Civil War south). Gradually develop interest by giving more details and information as they are presented. Is there a sub-plot, a smaller story within a story? These additional details form the rising action, the conflicting elements which will require some kind of resolution. Is one character a foil for another (as Robin is to Batman). Conflict means opposition: identify the person vs. person, or person vs. group, environment, nature, or self which is the conflict. Usually, when reading a story, the reader begins to anticipate the conflict from subtle clues given in the narrative. An author may employ foreshadowing (the servants overhear conversations in Uncle Tom’s Cabin) to warn or tell the reader of what the outcome will be. Every story should have enough conflict to make the reader wonder how the story will turn out. Explain how the plot is developed around the purpose of the story. Holding your reader in suspense without a lesson or moral to be learned is wasting their time (cf. television sit-coms and soap operas). A plotline lists the main events as they happen, although sometimes flashbacks and previous conversations are used to fill in details or purpose. Don’t try to tell everything, just those parts needed to help someone else understand the point, lesson, or moral. Lead up to the climax, then describe how the problem/conflict is solved. The difference between plot and story can be subtle. A story tells the events in order of sequence. A plot is a narration with emphasis on the connection of literary elements. Connect the events with the crisis and the resolution. Predictable narrative story lines are sometimes called formula plots (e.g., Hardy Boys mystery series or TV series). Finally, wrap up the loose ends, tell how it turns out and what lesson is to be learned. Did a character change due to events in the story? Was the author’s morality relative or Biblical? Did the author attempt values clarification through seemingly unsolvable moral dilemmas (when only ‘wrong’ is ‘right’)? What was the purpose of the story? Sum it up: identify genre, there may be several Describe setting, time period, location Plot Study and Analysis 2 www.thelmaslibrary.com introduce characters, do they represent ideas, are they stock, or a foil? identify conflict elements, support with quoted examples (plus references) main events, sub-plots rising action, is there foreshadowing, suspense, is it a formula plot (easy to figure)? identify climax/crisis, what driving force brought this about? falling action, conflicts resolved resolution, consequences, did they change, how will things be different? moral/lesson/purpose of story, (your opinions are valid and welcome additions here) Plot Study and Analysis 3 www.thelmaslibrary.com