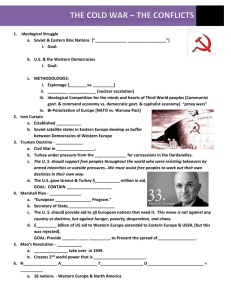

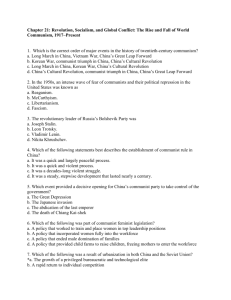

Introduction

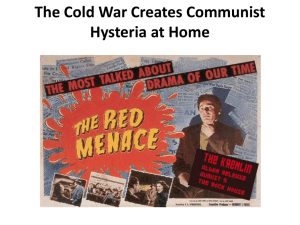

advertisement