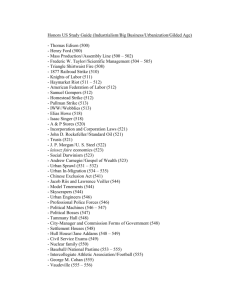

new perspectives on the 1984-5 Miners` Strike

advertisement

1 Economic History Society Annual Conference 26-28 March 2010 University of Durham Jim Phillips, Department of Economic and Social History, University of Glasgow, Lilybank House, Bute Gardens, Glasgow G12 8RT J.Phillips@lbss.gla.ac.uk The Moral Economy of the Scottish Industrial Community: new perspectives on the 1984-5 Miners’ Strike This paper makes a contribution to debates about the economic framework of industrial politics by examining aspects of the 1984-5 Miners’ Strike in Britain, focusing on developments in Scotland. It focuses on the material and moral resources available to the strikers. The strike against pit closures is generally understood in terms of peak level relations between the Conservative government, the National Coal Board (NCB) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), and the shifts in energy supply that decisively weakened the miners’ bargaining position. It is also often portrayed as a top-down imposition on the workforce and the industry by the ‘politically-motivated’ union leadership, and as a public order issue, with many arrests and prosecutions arising from the picketing of mines, steel works and other economic units.1 The literature on the miners’ strike includes accounts that look beyond high politics to analyse coalfield industrial relations and politics, sometimes through Martin Adeney and John Lloyd, The Miners’ Strike, 1984-5: Loss Without Limit. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul 1986; Paul Routledge, Scargill. The unauthorized biography, London, Harper Collins, 1993; David Stewart, ‘A Tragic “Fiasco”? The 1984-5 Miners’ Strike in Scotland, Scottish Labour History, 41, 2006, 34-50; Andrew Taylor, The NUM and British Politics. Volume 2: 1969-1995, Ashgate, Aldershot, 2005. 1 2 examination of the NUM, its leadership, officials, and strategy.2 Such analysis can be related to broader questions in industrial relations literature about union strategy, the meaning and extent of ‘militancy’, and ‘mobilization’ (or ‘mobilisation’) of union members in pursuit of a range of identified workplace, industrial and political goals.3 These are important approaches and questions, pointing to the value of empirical investigation. They do not readily explain, however, the varied patterns of community support for the year-long 1984-5 strike, other than suggesting that Nottinghamshire miners broadly opposed the strike because geological advantages made their pits easier to work and therefore their jobs safer, while in Yorkshire individual strike commitment was apparently shaped by personal variables, notably family background and occupational, political and union tradition.4 This paper analyses community support for the strike, including the involved engagement of women, and varied pit-level commitment, by examining material and moral resources. It leans to some extent on social movement theory, with the emphasis on resource mobilisation,5 demonstrates the social and economic embeddedness of industrial politics generally, and deepens understanding of the strike as a complex and multi-textured historical phenomenon. Two key research questions are asked. First, how far can the different levels of strike commitment at different pits be explained in terms of the comparative availability of material resources available to the strikers at different pits? Second, how far did trade unionists and their supporters in mining communities articulate a distinctively moral economic discourse in support of the strike? E. P. Thompson’s famous moral economy of the eighteenth century 2 Andrew J. Richards, Miners on Strike. Class Solidarity and Division in Britain, Oxford, Berg, 1996; Andrew Taylor, The NUM and British Politics. Vol. 2: 1969-1995, Aldershot, Ashgate, 2005. 3 John Kelly, ‘Long Waves in Industrial Relations: Mobilization and Counter-mobilization in Historical Perspective’, Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 4, 1997, 3-35. 4 J. and R. Winterton, Coal, Crisis and Conflict: The 1984-85 Miners’ Strike in Yorkshire, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1989. 5 Nick Crossley, Making Sense of Social Movements, Buckingham, Open University Press, 2002. 3 English crowd is adopted and adapted here,6 with the strike presented as a reemergence of a feature of earlier coalfield protests. This was the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century tradition of popular, direct action in the coalfields, involving women and children, and the ritualised humiliation of strike-breakers and colliery officials and managers. These accompanied and occasionally superseded ‘bureaucratic’, union-based procedures, especially in national disputes, notably in 1887, 1894, 1912 and 1921.7 This tradition had been revived in the strikes of 1972 and 1974, the first national disputes in the coal industry since the 1920s, and was even more sharply illustrated by the struggle to defend pits and local jobs in 1984-5, mediated by moral economic ideas about social resources and communal interests. Coal industry jobs, for instance, were ‘owned’ by the community as much as the individual employee or employer, to be retained within the community from one generation to the next, and this explains the complex and sometimes antagonistic response by many miners to those – especially younger men – who accepted redundancies or transfers to other pits from those that were closing or being threatened with closure. Picketing, at pits where workers broke the strike, may be understood in terms of a ‘moral economy’ discourse, with crowd discipline and goals highly evident. The ‘rough music’ of earlier crowd protests can likewise be ‘heard’ in the responses by strikers and their supporters, including perhaps especially female family members, to news of pit closures before the strike, with NCB officials verbally abused and physically confronted, and to those who returned to work during the strike. The day-to-day organisation and maintenance of the strike – including the physical sustenance of its supporters – similarly involved a ‘moral economy’ emphasis on equitable resource distribution and the mobilisation of the many material resources embedded in E. P. Thompson, ‘The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century’, in Customs in Common, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1991. 7 Alan Campbell, The Scottish Miners, 1874-1939. Volume One: Industry, Work and Community (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2000), 280-91. 6 4 industrial communities. These included the endeavours of coalfield women, in paid employment as well as in strike organisation, and the support of Labour-controlled local authorities which allowed strikers to defer council housing rents. Neither of these resources was available to miners in the great disputes of the 1920s, and provided some of the essential tools of strike endurance in 1984-5. Contrasting levels of endurance across the Scottish coalfields, however, can only partly be explained in terms of localised differentials in access to each of these resources. Moral resources – commitment burnished by ideological reserves compiled in pre-strike and indeed earlier historical experience – were important if less tangible variables. The paper builds on the author’s published work on industrial politics in Scotland and the UK in the 1960s and 1970s, and the origins of the 1984-5 miners’ strike in Scotland.8 It utilises a variety of perspectives from economic and social historical literature, and is based on NCB and NUM records and materials, Scottish Office records, the 1981 Population Census, reports in the daily press, and participant interviews conducted by the author. Material Resources and Strike Commitment The Scottish coalfield contracted steadily in the decades following nationalisation of coal in 1947, with the particularly biting closures of the 1960s accompanied by an important shift from relatively smaller village pits to relatively larger ‘cosmopolitan’ pits. By March 1984 most if not all of Scotland’s miners travelled to work by road – sometimes by car but in most instances bussed by the NCB – from mining communities that no longer had mines, to eleven cosmopolitan pits in East and West 8 Jim Phillips, The Industrial Politics of Devolution. Scotland in the 1960s and 1970s (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2008); Jim Phillips, ‘Workplace Conflict and the Origins of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike in Scotland’, Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 20, 2009, pp. 152-72; Jim Phillips, ‘Business and the Limited Reconstruction of Industrial Relations in the UK in the 1970s’, Business History, 51, 6 (2009), 801-16. 5 Fife, Clackmannan, Midlothian, West Lothian and Ayrshire. There was one surviving village pit: Polmaise, at Fallin in Stirlingshire. The ‘cosmopolitan’ pits were so called because they drew their workforces from a variety of sometimes quite widelydispersed localities, with distinct political and working cultures.9 In East Fife the Seafield and Frances workforces were drawn from a geographically extended ‘community’, while those who worked the thick seams of the Longannet ‘complex’ pits – servicing the va;st South of Scotland Electricity Board (SSEB) power station established at the end of the 1960s – of Solsgirth, Castlehill and Bogside at the junction of West Fife and Clackmannan were drawn from an even wider spatial territory. The miners of West Fife and Clackmannan were joined in the complex by men from North and South Lanarkshire, transferred when Bedlay shut in 1981 and Cardowan in 1983, and West Lothian, including those exiled from Kinneil when it closed at the end of 1982. This geographical dispersal loosened the connection between community and pit in the Scottish coalfields. Yet a common theme of oral testimony provided by strike participants to the author, and present too in the substantial ephemeral literature generated in the coalfields in the mid-1980s, was the restoration of community-centred activity and identity during the strike.10 This was important, for it was in the communities, fragmented and dispersed as they were, that the vital material resources were located for constructing strike commitment. Two are identified here: the provision of income to households with male members on strike through the wages of Married Women in Employment (MWE); and the suspension of costs to households with male members on strike where households were local authority tenants and the Labour-led local authorities deferred housing rents for the duration of the strike, examined here as Council Housing Density (CHD),. These two 9 Willie Clarke, Interview, 13 November 2009; Campbell, Scottish Miners. Volume One, p. 189 and Volume Two, 217-18. 10 Nicky Wilson, Interview, 18 August 2009; Catriona Levy and Mauchline Miners’ Wives, ‘A Very Hard Year’. 1984-5 Miners’ Strike in Mauchline, Glasgow, Workers’ Educational Association, 1985. 6 resources, calculated on the basis of data from the 1981 Population Census, are illustrated in Table 1. The CHD values in coalfield settlements were significantly higher than the overall Scottish value. The housing legacy of the pre-nationalised industry was mixed, with much pre-1947 private sector rented accommodation not fit for habitation by the 1950s and 1960s. Local authorities were obliged after the Second World War to make good this failing. The disappearance of the Central Fife village of Glencraig – dominated by the typical single-storey, terraced ‘miners’ rows’ housing, along the central artery – and the transfer of its inhabitants in the 1950s to the local authority housing of Ballingry, a few hundred metres to the north, is a good example. In 1981 CHD in Ballingry was 94 per cent.11 The MWE values are perhaps more noteworthy, with most coalfield settlements characterised by higher rates of economic activity among married women than in Scotland as a whole. The ephemeral literature generated by the strike emphasises the volume and range of paid work available to women, especially in the Lothians and Fife, including assembly work in manufacturing in addition to public and private service sector employment.12 This is spoken of too by strike participants recalling their own experiences: spouses working full-time continued to do so; spouses with one part-time job took a second and sometimes even a third part-time job to expand the household’s resources.13 The exception, it will be seen, was Ayrshire, where the narrower span of material sustenance was perhaps reflected in the crumbling of commitment in the final quarter of the strike. 11 For Glencraig see http://www.glencraig.org.uk; accessed 11 February 2010; Willie Clarke (who made this move), Interview, 13 November 2009; Census 1981 Scotland. Report for Fife Region, Volume 4 (HMSO, Edinburgh, 1983), Table 14, ‘Private Households in Permanent Buildings by tenure’, etc. 12 Ian MacDougall, Voices From Work and Home, Edinburgh, Mercat Press, 2001, pp. 141-2. 13 David Hamilton, Interview, 30 September 2009. 7 Table 1. Married Women in Employment (part-time and full-time) and Council Housing Density by Colliery in Scotland, 1981 Colliery MWE (per cent) CHD (per cent) Bilston Glen 53.7 63 Monktonhall 50.5 72.1 Polkemmet 48.7 84.3 Seafield 45.1 82.3 Frances 45.1 82.3 Killoch 39.4 82.2 Barony 39.4 82.2 Solsgirth 45.1 67 Castlehill 45.1 67 Bogside 45.1 67 Comrie 44.6 55.3 Polmaise 46.3 80.2 Scottish Coalfields 46.8 74.0 Scotland 45.2 54.6 Source: Census 1981 Scotland, HMSO, 1982, 1983.14 MWE and CHD are factors in the composition here of a Relative Potential Strike Endurance Index (PSE) by colliery for the Scottish coalfields, along with a third factor, the Militancy Index (MI), designed to capture the relative character of pit-level industrial relations going into the strike. This latter factor is important, for recent research published by this author demonstrates that managerial incursions on trade union rights and working practices, together with employee anxieties about the future of their pits, had precipitated serious colliery-level industrial disputes in the second half of 1983 and the first two months of 1984 at more than half of the Scottish mines, most notably Seafield and Monktonhall in Midlothian.15 14 Census material drawn from Reports for the various Regions: Central, Fife, Lothian and Strathclyde. 15 Phillips, ‘Workplace Conflict’. 8 Table 2. Pit-level Potential Strike Endurance Rankings in the Scottish Coalfields, 1984 Colliery MWE Rank CHD Rank MI Rank PSE Rank Seafield 4 2 3 1 Polmaise 4 6 1 2 Monktonhall 2 7 2 2 Polkemmet 3 1 7 2 Frances 4 2 5 2 Bogside 4 8 4 6 Castlehill 4 8 5 7 Killoch 11 2 7 8 Barony 11 2 10 9 Comrie 4 12 7 9 Solsgirth 4 8 11 11 Bilston Glen 1 11 12 11 Sources: see Figure 1 The PSE pit-level rankings are set out in Table 2. To recap, they were calculated by adding the three relative ranked variables set out in Figure 1: MWE, CHD and MI. Figure 1: Variables deployed to rank Pit-level Potential Strike Endurance Married Women in Employment (MWE) by District Councils in which collieries were situated or sufficiently adjacent to collieries for there to be a reasonable expectation that miners at particular collieries were resident in these local authorities. The MWE rate was calculated by adding full-time and part-time married women in employment. Council Housing Density (CHD) by District Councils in which collieries were situated or sufficiently adjacent to collieries for there to be a reasonable expectation that miners at particular collieries were resident in these local authorities. Militancy Index (MI): the sum at each pit of level of support for strike action against job losses and the National Coal Board’s pay offer in the national ballot held by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in October 1982 (data in Scottish Miner, December 1982) and the involvement in an evidently significant pit-level dispute, 1983-4, ‘significant’ here meaning of sufficient gravity to be recorded in NCB collierylevel minutes or reported in the national Scottish press. Polmaise, for instance, is ranked 1 for MI. It experienced a four week lock-out in the summer of 1983, and when its closure was announced in December 1983 the workforce was agitating for a national strike; 99.3 per cent of the pit’s NUM members voted for a strike in October 1982. In CHD terms Polmaise was ranked 6, and in MWE terms ranked 4. So the sum of its rankings was 11, the second equal lowest of 9 the twelve pits, alongside Monktonhall, ranked 2 in MI terms, 7 in CHD terms, and 2 in MWE terms. Seafield is ranked 1 in overall PSE terms, a combined ranking total of 9 resulting from an MI rank of 3, a CHD rank of 2 and an MWE rank of 4. The lowest overall PSE rank is shared by Bilston Glen and Solsgirth, both essentially owing to low MI and CHD rankings. This approach is not methodologically straightforward. The main problem, clearly, lies in establishing CHD and MWE values where there was a separation of mining communities from collieries, particularly the cosmopolitan pits of Seafield and Frances in East Fife, Barony and Killoch in Ayrshire, Monktonhall and Bilston Glen in Midlothian, and the Longannet complex. Polmaise itself, in the geographically large District Council of Stirlingshire, is also problematic. The solutions established are set out in Figure 2. Figure 2. Establishing MWE and CHD values for Scottish collieries in 1984 Seafield and Frances: CHD value to encompass identified mining settlements in Kirkcaldy District Council plus those in Dunfermline District Council settlements to the east of the M90, with Cowdenbeath at the western fringe; MWE value to encompass average of Kirkcaldy and Dunfermline value. Ayrshire pits: CHD and MWE values to encompass the aggregate of Cumnock and Doon Valley District Councils’ material. Bilston Glen: CHD value to encompass Bilston, Bonnyrigg, Loanhead, Penicuik, Dalkeith, Gorebridge, Mayfield; MWE value to encompass Midlothian District Council material Monktonhall: CHD value to encompass Dalkeith, Danderhall, Gorebridge, Mayfield and East Lothian District Council settlements; MWE value to encompass average of Midlothian and East Lothian values. Longannet complex (Bogside, Castlehill and Solsgirth): CHD value to comprise Clackmannan and Dunfermline District Council settlements to west of M90; MWE value from average of Dunfermline District and Clackmannan District. Comrie: CHD and MWE values on basis of Dunfermline District. Polmaise: CHD comprising average Bannockburn and Carseland in Stirlingshire; MWE on basis of Stirlingshire. Polkemmet. CHD comprising Whitburn and Armadale; MWE on basis of West Lothian District Council. The PSE was then contrasted with Actual Strike Endurance (ASE) exhibited during the strike. This, again, was a relative ranking index, calculated on the basis of data compiled during the strike by the NCB’s Scottish Area, and passed to the Scottish 10 Office, on numbers of miners working at pits between March 1984 and March 1985. This material is retained in Scottish Office daily situation reports, archived in the National Archives of Scotland (NAS). This shows the relatively solid nature of the strike across Scotland until the autumn of 1984. Only at Bilston Glen were substantial numbers working before this point, and so this pit is clearly ranked 12 in ASE terms. Numbers working escalated elsewhere first at Monktonhall, possibly in the context of the apparent harassment of NUM delegates there from October onwards. This included a lengthy stretch of imprisonment before trial on public order charges of the union branch delegate, together with financial inducements to return before the end of November, which also stimulated some noteworthy resumption of work in Ayrshire. Yet Monktonhall is ranked at 8 in ASE terms because the volume of strike-breaking was stemmed there to some extent in January and February 1985, possibly bolstered by the outcome of the branch delegate’s trial at Edinburgh Sheriff Court, where he was cleared of all charges. 16 The strike remained solid in East Fife until January. Table 1 showed that the Longannet pits – Bogside, Castlehill and Solsgirth – had access to lower than coalfield average resources, in terms of MWE and CHD. But the numbers working at the complex before February, like Comrie in West Fife, were in single fingers. So these pits top the ASE rankings, along with Polmaise, where nobody returned until one week after the strike was officially called off in March. Table 3. PSE and ASE in the Scottish Coalfields, March 1984 to March 1985 Rank PSE ASE 1 Seafield Polmaise; Bogside 2 Polmaise; Monktonhall; Polkemmet 3 Comrie; Solsgirth; Castlehill 4 5 Frances 6 Bogside Seafield 7 Castlehill Frances 8 Killoch Monktonhall 9 Barony; Comrie Polkemmet 16 National Archives of Scotland (NAS), SEP 4/6029/1, Scottish Office, Situation Reports, 20 and 21 December 1984. 11 10 11 12 Bilston Glen; Solsgirth Barony Killoch Bilston Glen The strike, of course, was about the future of the industry. Not all pits were equally affected by this question. Polmaise was strongly in favour of a strike because its future was immediately jeopardised by NCB closure plans. Bilston Glen, by comparison, is often cited as a ‘superpit’ with a big future which rational economic miners defended by strike-breaking.17 Assumptions about good performance and low strike commitment are worth testing, however, not least because pre-strike collierylevel minutes of consultation meetings at Bilston Glen indicate the same type of industrial tension, inspired by management worries about production and output, and involving allegations of poor worker effort and low morale, that were evident at pits – notably at Seafield and Monktonhall – which exhibited higher degrees of ASE in 1984-5.18 So Table 5 reprises ASE, but measured this time against a PSE adjusted to accommodate pre-strike, pit-level performance. Collieries were ranked in this latter category on the basis of data compiled by the Monopoly and Mergers Commission’s report on the coal industry, published in 1983, reproduced here in Table 4, with ranked performance the sum of three ranked factors: output per manshift, costs per tonne of production, and losses per tonne of production.19 Table 4. Performance Measures from NCB Scottish Collieries, 1981-82 Colliery Saleable Output Per Operating Operating Loss Output Manshift Costs (£ per (£ per tonne) (000s (Tonnes) tonne) tonnes) Bilston Glen 892 2.06 42.70 4.60 Monktonhall 895 2.31 38.30 8.20 17 David Stewart, The Path to Devolution and Change. A Political History of Scotland under Margaret Thatcher (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2009), 96-7. 18 NAS, CB 229/3/1, NCB Scottish Area, Bilston Glen Colliery, Minutes of Colliery Consultative Committee (CCC), 4 October 1983, 30 November 1983. 19 Monopolies and Mergers Commission, National Coal Board. A Report on the efficiency and costs in the development, production and supply of coal by the National Coal Board, Cmnd. 8920, Volume One and Volume Two. HMSO, 1983. 12 Polkemmet 390 1.39 54.50 9.00 Seafield 848 1.98 44.10 8.70 Frances 254 1.85 53.10 17.80 Killoch 698 1.58 49.0 16.70 Barony 227 2.00 50.20 13.80 Solsgirth Castlehill 1955 3.19 31.20 1.50 Bogside Comrie 374 1.61 48.30 16.60 Polmaise N/A N/A N/A N/A NCB Average 2.4 39.48 Source: Monopolies and Mergers Commission, National Coal Board, Volume Two, Appendix 3.5 (a). Notes: Figures for Solsgirth, Castlehill and Bogside are composite for Longannet complex; Polmaise was classed as a Development Pit in 1981-2, not producing coal. Performance is deployed in Table 5 as a positive factor in building strike endurance, contrary to standard assumptions about good performance undermining pit-level commitment. ‘Good performance’ in Scotland was, of course, relative, as the NCB average output per manshift and operating costs per tonne in Table 4 indicates, but perhaps because of this it represented a useful resource around which strikers could organise, to protect something valuable with perceived long-term potential. Table 5: Adjusted PSE, ASE and (pre-strike) Performance in Scottish Coalfields, March 1984 to March 1985 Rank Adjusted PSE (performance ASE Performance as positive factor) 1 Seafield; Monktonhall Polmaise; Bogside Bogside, Solsgirth, Castlehill 2 3 Bogside Comrie; Solsgirth; Castlehill 4 Castlehill Monktonhall 5 Frances; Polkemmet Bilston Glen 6 Seafield Seafield 7 Polmaise Frances Barony 8 Solsgirth Monktonhall Comrie 9 Killoch Polkemmet Killoch 10 Bilston Glen Barony Polkemmet; Frances 11 Barony Killoch 12 Comrie Bilston Glen Polmaise Polmaise slips in this performance-adjusted PSE because it was not producing coal in 1981-2. It had since 1978 been classified by the NCB as a Development Pit, with 13 work concentrated on securing underground drivages to the Longannet complex. This development work was ongoing when the pit’s closure was announced in January 1984.20 The other prime movers within this performance-adjusted PSE are the Longannet complex pits, where output per manshift in 1982 exceeded the average for all NCB holdings, and production more generally was boosted by the miles of underground conveyors that brought coal directly into the power station. Bilston Glen, which moves down from tenth to eleventh with the addition of the performance-related factor, was presented as the NCB’s prime Scottish asset by its new Director in the autumn of 1983, Ian MacGregor, who provocatively contrasted the alleged success of the men there with the ‘second division’ efforts of nearby Monktonhall.21 Yet Bilston Glen’s performance in 1981-2, captured in Table 3, together with the concerns expressed by managers privately at pit-level about production there in 1982 and 1983,22 rather belie this characterisation, which strike participants recall as a wilful attempt to weaken the Midlothian miners by dividing them.23 These mixed material signals duly point to the importance of examining the additional variables embodied in the Scottish coalfields’ moral resources. The Moral Economy and Moral Resources A broad assumption – usually implicit – of much twentieth century labour historiography is that the process of industrialisation in Britain was accompanied by a shift in the character of labour organisation and protest, with a transition in values from those of the moral economy to the political economy, matched in organisational and functional terms with a more or less linear trend to bureaucratisation and 20 Courier & Advertiser and The Scotsman, both 27 January 1984. Glasgow Herald, 21 September 1983. 22 NAS, CB 229/3/1, Bilston Glen CCC, 13 March, 26 May, 26 July and 8 September 1982; 7 September, 4 October and 2 November 1983. 23 Eric Clarke, Interview, 25 August 2009; David Hamilton, Interview, 30 September 2009. 21 14 negotiation with employers, chiefly over the terms of labour deployment: wages and conditions of employment.24 This assumption has been unpicked a little in recent decades, partly owing to the impact of social history in the 1960s and 1970s – including the work of E. P. Thompson – and partly due to the influence of feminist thinking, and to an extent also as a result of post-modernism. The manner in which twentieth century trade unions and industrial relations were infused with customs and expectations is certainly now more readily understood and accepted than it was three or four decades or so ago.25 The case of the miners’ strike in Scotland readily illustrates this, with moral economy expectations and behaviour evident and to some extent – and admittedly in slightly intangible ways – representing an additional variable in the shaping of pit-level strike commitment. It is suggested here that something amounting to a Moral Economy Variable (MEV) might be useful in explaining, for example, the different strike histories of the Midlothian pits, which after all drew on similar material resources in terms of Married Women in Employment and Council Housing Density. The MEV may also help to explain further the eventual crumbling of the strike in Ayrshire, despite its higher than coalfield average CHD value, and the solidity of the strike at the Longannet complex pits of Bogside, Castlehill and Solsgirth, which belied their below coalfield average CHD and MWE values. The MEV seems to have been particularly strong at Polmaise, which as the only real surviving ‘traditional’ village pit, was to an extent distinct in Scotland. Unlike others, and perhaps arising from this, its union officials and representatives were not connected to the Communist Party, and its broader social loyalties were a different hue. Men and women of Irish Catholic origin were present, with the Cowie miners A. E. Musson, ‘British Trade Unions, 1800-1875 (1972), in L. A. Clarkson, British Trade Union and Labour History. A Compendium, Houndmills, Macmillan, 1990. 25 Campbell, Scottish Miners; Neville Kirk, Custom and Conflict in the ‘Land of the Gael’: Ballachullish, 1900-1910, London, Merlin Press, 2007. 24 15 who spoke of their fortnightly Saturday afternoon pilgrimage to Parkhead,26 but there are suggestions too of powerful Protestantism and even Orangeism.27 NUM officials, delegates and activists from elsewhere in the coalfield certainly regarded Polmaise men as different: harder to predict, less easy to influence.28 Yet they were instrumental in driving forward support for the strike in Scotland in January and February 1984,29 and enforcing it on 12 March, the first day of the stoppage, when they arrived by coach to picket out Bilston Glen, which NCB and Scottish Office officials thought would otherwise have continued working.30 Polmaise men were moved by moral as well as ‘rational’ economic factors. They articulated a profound sense of injustice when the pit, their prime community resource, was threatened with closure. Their representatives spoke about the ‘crimes’ associated with abandoning the millions of pounds of public expenditure that had been invested in developing the pit. These were, literally, sunk assets, the abandonment of which would be morally repugnant as well as economically irrational.31 This was the NUM position in Scotland more broadly, and remains so, with lost coal reserves and pit workings seen as more or less criminal sabotage by NCB officials and government ministers. Unfavourable comparisons are made between the allegedly punitive treatment of strikers on picket lines – with perhaps unusually hefty fines for public order offences, along with dismissals and therefore lost redundancy rights and payments – and the financial rewards enjoyed by NCB officials, chiefly Albert Wheeler, Scottish Area Director, who Steve McGrail and Vicky Patterson, ‘For as long as it takes!’ Cowie Miners in the Strike, 1984-5, 1985. 27 Terry Brotherstone and Simon Pirani, ‘Were There Alternatives? Movements from Below in the Scottish Coalfield, the Communist Party, and Thatcherism, 1981-1985’. Critique, 367(2005), 99-124. 28 Eric Clarke, Interview, 25 August 2009; Nicky Wilson, Interview, 18 August 2009. 29 Scottish Mining Museum, Newtongrange (SMM), National Union of Mineworkers Scottish Area (NUMSA), Executive Committee (EC) and Minutes of Special Conference of Delegates, 13 and 20 February 1984. 30 NAS, SOE 12/571, J. Hamill, Scottish Home and Health Department, ‘Miners’ Strike: Picketing at Bilston Glen Colliery, Midlothian’, 13 March 1984. 31 John McCormack with Simon Pirani, Polmaise: the fight for a pit, London, Index Books, 1989. 26 16 encouraged or at least oversaw the loss of many hundreds of millions of pounds worth of underground public assets.32 At Polmaise two other moral economy strands were evident, which were observable at other pits, in other communities, to some extent: crowd involvement, with miners supported by women and sometimes children; and the characterisation of jobs as collective assets or resources. Albert Wheeler encountered the force of the crowd at Polmaise himself, in July 1983 when he announced a lock-out after the workforce refused to accept a handful of men that the NCB was seeking to transfer from Cardowan in Lanarkshire, which was being run down prior to closure. The Polmaise men and women believed that this broke an accord whereby locals transferred in the recent past to the Longannet complex would have the chance to return to their ‘home’ pit. Wheeler was harried and abused, with women colourfully to the fore.33 Children were present too, and the agency exerted by younger people was later a feature of the strike. At Ballingry on 7 June 1984 about one hundred twelve to fourteen year olds left classes in the village junior secondary school to prevent lorries from accessing a nearby open cast mine. This was reported in the miners’ paper in Scotland, and recalled proudly 25 years later by Willie Clarke, local councillor and union official at Seafield.34 Crowd action during the strike was often concentrated outside pits, goading and abusing miners who sought to work, or near the homes of these men. An early example was the hounding of a surface worker from the Longannet complex who broke the strike in June, Jim Pearson, whose home in Culross was encircled for several days by dozens of men and women, and whose van windscreen was smashed on several occasions.35 Pearson was given the protection of up to sixty police officers on each day that he reported for work, to the private annoyance of 32 Nicky Wilson, Interview, 18 August 2009; Eric Clarke, Interview, 25 August 2009. The Scotsman, 2 and 7 July 1983. 34 Scottish Miner, June 1984; Willie Clarke, Interview, 13 November 2009. 35 The Scotsman, 28 June 1984. 33 17 Fife’s Chief Constable, who regarded this as a misallocation of resources, and earned the praise of Scottish Office ministers,36 but he was ridiculed by strikers who refused to accept that he was a ‘proper’ miner.37 Pearson and other strike breakers also drew a particularly gendered form of crowd opprobrium. They were characterised especially by female supporters of the strike as inferior types of men. Their masculinity was flawed by the act of strike-breaking, usually linked to some other personality disorder, often alcoholism and sometimes a gambling addiction that may have contributed to severe financial problems that returning to work was designed to ease. These men were ‘weak individuals’, and often well known to the NCB, strike participants recall, because of their poor pre-strike disciplinary records, and were vulnerably open to managerial entreaties to return to work as a result.38 During the strike women in conversation with reporters cited the cases of particular strike-breakers who had been protected from dismissal for disciplinary offences by the union before the strike. This gravely compounded their act of betrayal during the strike.39 The question of transfers, evident in the July 1983 tension at Polmaise, arose from the second crucial moral economy issue: jobs as collective or social resources rather than the property of the employer or the individuals who occupied them. They were therefore to be preserved for the benefit of the community, including its future inhabitants. This coloured the attitude of the coalfield crowd to the related question of voluntary redundancy. Jobs could not be ‘sold’ by miners for redundancy payments. This explains how the closure of Cardowan in 1983 ignited a series of pit-level disputes, including the Polmaise lock-out, with the Lanarkshire men who accepted 36 NAS, SEP 4/6027, Situation Reports, 28 and 29 June, 6 and 18 August 1984; Note by Jane Morgan, Private Secretary to Michael Ancrum, 6 July 1984, and Note by R. Patton, Police Division, Scottish Home and Health Department (to Jane Morgan), 11 July 1984. 37 McGrail and Patterson, Cowie Miners. 38 Nicky Wilson, Interview, 18 August 2009; Iain Chalmers, Interview, 30 July 2009; David Hamilton, Interview, 30 September 2009. 39 Jean Stead, Never the Same Again. Women and the Miners’ Strike, 1984-5, London, The Women’s Press, 1987. 18 transfers or redundancies payments regarded as ‘renegades’.40 At Cardowan when closure was announced by Wheeler, in May 1983, the average age of the 1100 or so who worked there was 39.41 This is important, for the moral economy view of transfers and redundancy was age sensitive. Older miners, aged 50 and up, and especially aged 55 and up, and with long service to the industry, were not criticised for accepting redundancy. Monktonhall especially, and Seafield to an extent, were reportedly pits with relatively young workforces by the end of 1983. Few older miners, and certainly hardly any aged 55 and up, still worked there. Men in this age category had accepted either industry-wide or pit-level severance terms since 1980, when the Coal Industry Act’s emphasis on financial self sufficiency for the NCB by 1984 had focused managerial minds on cost reduction, and stimulated investment in redundancy packages, according to Ned Smith, the NCB’s Industrial Relations Director General.42 Bilston Glen was different, however. David Hamilton, Monktonhall’s NUM delegate, recalls that the NCB deliberately held older miners at Bilston Glen, while offering redundancy terms to their neighbours at Monktonhall. This may have been the central factor that shaped the contrasting levels of strike commitment at the Midlothian pits. The older men at Bilston Glen broke the strike precisely because they were tantalisingly close to the end of their working lives and wished to remove any possible obstacle to the collection of redundancy terms, which were linked to length of service. They returned to work early, in other words, so that they could leave the industry early.43 The view that longer serving miners would bear disproportionately the high costs of dismissal, as opposed to enjoying the fruits of redundancy, also it would seem shaped the crumbling of the strike in Ayrshire in January and February 1984. Here it was believed, wrongly, that the NCB could legally sack miners who had been on strike continuously for a year. Men dismissed in 40 SMM, NUMSA, EC, 12 July 1983, and Minute of Special Conference of Delegates, 12 July 1983. 41 Glasgow Herald and The Times, both 14 May 1983. 42 Ned Smith, The 1984 Miners’ Strike. The Actual Account, Whitstable, 1997, pp. 12-15. 43 David Hamilton, Interview, 30 September 2009. 19 this manner would lose redundancy benefits, including financial compensation.44 The NUM’s Scottish Area Strike Committee also heard evidence in February 1985 that the NCB had directly contacted about 1200 older men who were still on strike in Fife, Stirling and Clackmannan, indicating that they would be offered highly favourable redundancy terms if they returned to work for just four weeks.45 This perhaps contributed to the eventual weakening of the strike in East Fife, although the position at Longannet’s pits and Comrie hardly altered, to the surprise and evident annoyance of Scottish Office officials.46 The disintegration of the strike in Ayrshire might be attributed to one further, slightly intangible moral economy variable: the engaged involvement, as opposed to rational material support, of women. In Ayrshire, it should be emphasised, rational material support was relatively constrained by the proportion of Married Women in Employment, lower than anywhere else in the Scottish coalfields. The extent of engaged female involvement – local, regional and national public speaking, campaigning, fund- and consciousness-raising – in Ayrshire was also apparently limited, particularly in and around New Cumnock. The essential problem was male chauvinism. This was a feature elsewhere in the Scottish coalfields. Willie Clarke still laments the sexism of some miners, notably around Comrie, but more broadly in Fife there was some reconstruction of gender politics, which he gladly recounts.47 Certainly the moral leadership as well as material support of women was central to strike endurance in Fife. Daily reports from the NUM’s strike centre at Dysart, encompassing Frances and Seafield Collieries, outline especially from May 1984 onwards the growing involvement of women in the direction as well as the maintenance of the strike.48 This trend was reportedly evident at Monktonhall too.49 Levy and Mauchline Miners’ Wives, ‘A Very Hard Year’. SMM, NUM Scottish Area, Strike Committee, 18 February 1985. 46 NAS, SEP 4/6029/1, Scottish Office, Situation Report, 11 February 1985. 47 Willie Clarke, Interview, 13 November 2009. 48 Kirkcaldy Museum, 75.3/1/1, NUM Dysart Strike Centre, Reports, May to June 1984, outline. 44 45 20 The close engagement of women with the strike in Fife and parts of Midlothian may not have been related to female labour market participation. In Midlothian this was above the coalfield average but in Fife just marginally below. It may instead have owed something to the Communist tradition, especially in Fife, although Communists were sexists too. One measure of changing mores in this tradition, however, can perhaps be viewed in the pages of the Communist-influenced Scottish Miner, which from 1967 carried exploitative pictures of women. Introducing this ‘new free service’ had been ‘curvy Carmen Dene. For the backshift worker who did not know, Carmen (38-22-36) has appeared on TV in “The Avengers” and “Armchair Theatre”. Watch it, lads!’. But this ‘service’ was discontinued from February 1974, and during the 1984 strike women were portrayed as taking a leading role,50 and the NUM Scottish Area lobbied after the strike to open full-time membership to women. Various strike participants in this connection recall the words of Michael McGahey, Scottish Area President and National Vice President, and lifelong Communist, to the effect that a working class movement without women is like a bird with one wing: it cannot fly.51 Conclusion This paper has ventured that support for the 1984-5 Miners’ Strike, at least in Scotland, was very much a matter of material and moral resources and variables. Material resources shaped the capacity for strike commitment to some extent: the suspension of rent commitments for local authority tenants in Labour controlled areas and the provision of income from working wives were the economic building blocks of Jean Hamilton, ‘Give us a Future, Give us our Jobs!’, in Vicky Seddon, (ed), The Cutting Edge. Women and the Pit Strike, London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1986, pp. 211-21. 50 Scottish Miner, October 1967, January and February 1974, and June 1984. 51 Iain Chalmers, Interview, 30 July 2009; Willie Clarke, Interview, 13 November 2009. 49 21 the strike. But in themselves these material variables do not explain pit-level varieties of strike commitment: between, for instance, Bilston Glen and nearby Monktonhall, or the intense solidarity of the Longannet complex, where rates of Council Housing Density and Married Women in Employment were actually lower than the Scottish coalfields average. Other material factors were therefore of apparent importance, including the strong performance record of the Longannet complex, which gave the men there something to defend, and the pit-level pattern of pre-strike industrial relations, which sharpened tensions and apparently developed a potential for lengthier strike endurance at some pits: Polmaise, certainly, and Seafield, perhaps, as well as Monktonhall. The difference between Bilston Glen and Monktonhall may, however, also have been a consequence of the less tangible Moral Economy Variable (MVE) that was examined in the second half of the paper. Revolving around the engaged role of the community, including women, this is not straightforward, complicated above all, perhaps, by the partial dislocation of community from colliery that was the consequence of industrial restructuring in the 1960s, as village pits gave way to cosmopolitan collieries. A further important moral variable related to attitudes towards job ownership and redundancy: could individual miners ‘sell’ resources that essentially belonged to the community? This too was slightly problematic in the sense that attitudes to this moral question were possibly shaped at pit-level by an important material difference: the age profile of the workforce. Pit-level strike commitment was apparently increased by the relative youth of the workforce: younger men had a greater material investment in a strike against closure. The paper nevertheless illustrates the contrasting presence and importance in different localities of moral economy attitudes and behaviour. Younger men may, after all, have more readily accepted the rational economic case for closure of their pit, and more quickly sought other ways of making a living, had they not been morally emboldened by arguments about community resources and obligations. Of further note, perhaps, in 22 generating strike commitment, and evident particularly throughout Fife, was a greater local or community emphasis on a more equitable – or less inequitable – division of labour by gender, and stronger approbation for the positive and engaged moral as well as material role of women. Jim Phillips is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Economic and Social History at the University of Glasgow. His recent publications include The Industrial Politics of Devolution: Scotland in the 1960s and 1970s (Manchester University Press, 2008), ‘Workplace Conflict and the Origins of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike in Scotland’, Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 20, 2009, pp. 152-72, and ‘Business and the Limited Reconstruction of Industrial Relations in the UK in the 1970s’, Business History, forthcoming, 2010.