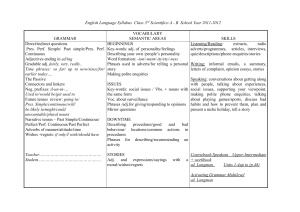

The Syntax andSemantics

advertisement

Arabic Perfect and temporal adverbs

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

Languages use grammaticalized inflections (GIs), auxiliaries (Auxs), and

temporal adverbials (PPs or NPs, etc.; = Advs) to express various kinds of

temporal reference (TR). It is largely acknowledged in the literature that

GIs are ambiguous or underspecified with respect to TR, and that their

forms, even when identical, may lead to different interpretations within the

same language, or across languages (even from the same family). Advs can

be equally ambiguous in producing various temporal meanings. Common

categories assumed to contribute to (as well as organize) linguistic TR include Tenses (Ts), Aspects (Asps), and Aktionsarts (Akts). They project as

functional categories in scopal hierarchical syntactic structures. The latter

are assumed to reflect morphosyntactic and lexical properties of these

components, and organize their contribution to TR meanings. The descriptive program of crosslinguistic and language specific temporalities appears

then to be to identify which ingredients of TR grammar and meaning are

contributed by which GI, Aux, or Adv, or their combinations. The aim of

this article is essentially to describe some salient properties of the Arabic

Perfect (= Perf) within this perspective, by taking into account some crosslinguistic variation.1

The study of the Arabic Perf is not only of interest for its own sake, but it

is of central importance to understanding how the various ingredients of

the Arabic temporal/aspectual system are organized, compared to other

language systems. First, Perf interacts significantly with Past and Perfective (= Pfv), exhibiting various TR ambiguities, which need to be properly

identified, in parallel to the examination of the distribution and interpretation of collocational Advs. Second, various kinds of Perf documented in

the literature will be investigated here, to see whether they are instantiated

in Arabic, and how they exhibit similar or different properties. My approach to general semantic and morphological questions is based on the

assumption that there are natural (or canonical) mappings between temporal/aspectual forms and their semantic interpretations. Forms are productively ambiguous, but they are associated with abstract syntactic and selective properties, which then provide room for language specific differentiations. The latter are captured properly only if the semantics involved is

made precise, to allow accurate comparative work2. My grammatical description of TR relations, expressions, and distributions will typically make

use of a hierarchical architecture in which Perf is generated higher than

Asp (which is basically Pfv) as some ‘relative’ T or T2. The latter is

70

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

lower than the ‘deictic’ or ‘absolute’ T, or T1 (denoting Past, Present, or

Future). The core temporal architecture that I adopt is then as follows:

(1)

T 1 ( Past)

T 2 ( Perf )

Asp ( Pfv)

VP ( Tel)

1. The Arabic T/A-system

The Arabic system of T/A expressions exhibit a number of typical properties that are worth describing within a comparative perspective. Four of

these properties are briefly investigated in this section.

1.1.

Polyfunctionality of T/A-forms

The T/A system is dominated by the polyfunctionality of its T/A forms.

First, there is no morphological distinction between an inflected root verb

and an embedded ‘participle’: both are finite, and they carry the same temporal and agreement features. In other words, the form of expression of T1

(and Agr1) and T2 (and Agr2) is identical, and the morphology is not discriminatory as far as the T1/T2 distinction is concerned3. This uniformity is

exemplified in the two following pairs of constructions. The first pair contrasts the two basic simple tenses available in the system: Past and Present

(or non-Past), which express semantic PAST and PRESENT, respectively:

(2) katab-a r-risaalat-a.

wrote-3 the-letter-acc

‘He wrote the letter.’

(3) y-aktub-u

r-risaalat-a.

3-write-indic the-letter-acc

‘He is writing the letter.’

The second pair contains the same forms embedded under auxiliaries, and

functioning as Perfect and Imperfect ‘participles’:

(4) kaan-a katab-a r-risaalat-a.

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

71

was-3 wrote-3 the-letter-acc

‘He had written the letter.’

(5) kaan-a y-aktub-u

r-risaalat-a.

was-3 3-write-indic the-letter-acc

‘He was writing the letter.’

In other words, the ‘tense’ forms can also function as ‘aspect’ forms.

Second, the duality between Past/Present and Perfect/Imperfect is further complicated by the fact that these forms may express a Perfective/Imperfective opposition. For example, Past in (2) is interpreted as

PFV, and Present in (3) or (5) as IPFV. To be neutral and for ease of comprehension, I will designate the two forms as Past/Pres and Perf/Imperf

interchangeably and depending on contexts. I will also refer to their varied

semantics by capital letters, when necessary. Clearly, the terminological

dispute about morphological forms is meaningless in the absence of precise

and clear-cut semantic associations.

1.2.

The PresPerf-split: synthesis and analysis

A second characteristic feature of the Arabic T/A system is the synthetic/analytic split of its PresPerf forms. The synthetic form (which is homophonous with that of the Past) is limited to PRES interpretations, which

will be detailed in this article. It is exemplified in (6), which can also have

a Past interpretation:

(6) jaraa.

ran

‘He has run.’

Analytic forms, however, in which the Pres auxiliary kaana ‘be’ is overtly

realized, do not have PRES interpretation. They normally express a futurate Perf (= FUTPERF), as in (7), and they collocate with future time adverbs:

(7) ?-akuunu

?anhay-tu r-risaalat-a

g*adan.

I-am

finished-I the-letter-acc tomorrow-acc

‘I will have finished the letter tomorrow.’

They can also express ‘iterative’ readings, as in (8):

(8) bi-haad#aa y-akuunu l-fariiq-u

qad

sajjala

xams-a

72

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

with-this

is

the-team-nom already scored

five

marraat-in.

times

‘With this, the team has already scored five times.’

This situation is partly comparable to that of Portuguese, where the PresPerf is expressed by a simple form (which is also ambiguous with the

Past), as in (9), but the analytic form expresses only a habitual Perfect, as

in (10):4

(9) Comi.

ate

‘I have eaten.’

(10) Agora jà

tem comido.

now

I

have eaten

‘Now I have taken the habit to eat.’

It is unlike the situation in Germanic or Romance, where the PresPerf, in

addition to the Past and further meanings, is expressed by an analytic Perf.

In German, for example, the PresPerf co-occurs with Past, Pres, and Fut

adverbs (cf. Musan (2001)):

(11) Hans

Hans

ist

is

gestern

um zehn weggegangen.

yesterdayat

ten left

(12) Hans

Hans

ist

is

jetzt weggegangen.

now left

(13) Hans

Hans

ist

is

morgen

tomorrow

um

at

zehn weggegangen.

ten left

As we will see, this split is not without consequences for dividing lines of

interpretations and/or ambiguities, as well as crosslinguistic characterizations.

1.3.

The Past-split: simple Past-Pfv and complex Past-Impfv

A third important feature of the T/A system is that it exhibits also an aspectual split with respect to the form of expression of aspectual values for

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

73

Past. Simple Past is associated with Perfective, whereas Past Imperfective

must be expressed by two separate finite forms: the auxiliary in the Past,

and the thematic verb in the form of the Pres. The two contrasting forms

exhibiting the split are given in (14) and (15), respectively:

(14) ?anhaa r-risaalat-a.

finished the-letter-acc

‘He finished the letter.’

(15) kaana y-unhii r-risaalat-a.

was

3-finish the-letter-acc

‘He was finishing the letter.’

The letter is finished in (14), but not in (15). This split is partly comparable

to that of English simple Past and Past Progressive. It contrasts with the

double synthetic nature of this opposition found in e.g. French (‘passé simple’ vs. ‘imparfait’) or Italian (‘passato remoto’ vs. ‘imperfetto’).

There are various ways to assess the perfective nature of the simple

Past. One argument comes from the behavior of the Past in SOT contexts.

In complement clauses, the simultaneity with the past is solely acceptable

if the Present/Imperfect form is used (i.e. no SOT effect is possible, just

like the situation in Japanese or Hebrew):5

(16) qaal-a l-ii

?inna-hu y-aktub-u r-risaalat-a.

said-3 to-me

that-him

3-write

the-letter-acc

‘He said to me that he was writing the letter.’

The use of the Past/Perfect does not yield that interpretation:

(17) qaal-a l-ii

?inna-hu katab-a r-risaalat-a.

said-3 to-me

that-him

wrote-3 the-letter-acc

‘He said to me that he wrote the letter.’

In (17), there is no overlapping of the writing and the saying, unlike the

situation in (16). The writing is rather anterior to the saying (with a shifted

Past reading). This situation is in contrast with SOT behavior in complement clauses in English, where the embedded verb can be interpreted as

anaphoric (or simultaneous, with the meaning ‘Mary is ill’):6

(18) John said Mary was ill.

Giorgi & Pianesi (1995) compare languages which possess Imperfect (like

Italian) with languages that do not (e.g. German or English). They observe

74

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

that Italian Imperfect is a dependent anaphoric tense, which denotes Present-under-Past tense, the Past being provided normally by the matrix verb.

Moreover, the (simple) Past cannot be used in this language as dependent.

In embedded contexts, only Imperfect can be used, with an SOT-effect.7 In

contrast, languages like German use Past (ambiguously) as dependent or

non-dependent, the latter being neutral with respect to perfectivity. It can

be read either way, as simultaneous (Imperfective) or non-simultaneous

(Perfective):

(19) Hans sagte, dass Marie einen Apfel aß.

a. Hans said that Mary was eating an apple.

b. Hans said that Mary ate an apple.

In (a), the simultaneous reading is available, and Past is interpreted as Imperfective. In (b), Past is Perfective, and the simultaneous interpretation is

excluded. Thus (simple) Past is necessarily Perfective in Italian, but not so

in German. The conclusion then is that if a language has an Imperfect Past,

as opposed to a simple Past, the latter cannot be used as dependent in embedded contexts. On the other hand, the Imperfect is dependent and used to

denote simultaneity. In languages in which the Past is unspecified, it can be

used as dependent/simultaneous. Arabic is close to Italian in this respect.

Past is Perfective and non-dependent, contrary to Imperfect, as illustrated

above.

A second argument comes from the availability of continuous readings.

Consider e.g. (6), expressing a Past activity (repeated here as (20) for convenience), and its Past Imperfective counterpart, given in (21):

(20) jaraa.

ran

‘He ran.’

(21) kaana r-rajul-u

y-ajrii.

was

the-man-nom 3-run

‘The man was running.’

In (20), the event is completed or terminated. It cannot be further extended.

This is in contrast with (21), which is non-terminated and can be extended.

Hence the sequence in (22) can be used after (21), but it leads to ungrammaticality after (20):

(22) [...]

wa maa

zaala y-ajrii.

and still

3-run

‘and he is still running.’

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

75

In fact, the combination of (20) and (22) can be acceptable, but only if two

events are involved, one terminated to make the first clause true, and one

non-terminated and ongoing at UT, to make the second sequence possible.8

1.4.

The Past/Perf-ambiguity

A fourth significant property of the system consists in a genuine

Past/Perfect ambiguity of the Past/Perf form. As observed above, there is

only one temporal (suffixing morphology) in Arabic which can express

both PAST meaning and PRESPERF meaning. Thus (2) or (6) above are

ambiguous between what I represent in a very sketchy way as (23) and

(24), using a simplified Reichenbachian representation of time:

(23) ET, RT < UT

(24) ET < RT, UT

In the first representation, the Perf form is expressing PAST tense, and in

the second PERFECT ‘aspect’. The representation in (23) raises no significant problem. That in (24) is more disputable. I will ignore the potential

objections for the moment, and focus only on the fact that PAST specifies

a reference time (RT) which is prior to the utterance time (UT), while

PERFECT does not. To the extent that an anteriority component is involved in the PERF interpretation, that anteriority should involve other

argument times than UT. This subsection provides grounds for assessing

that the Past/PresPerf ambiguity represented here is genuine, rather than

thinking of it as an ambiguity arising within the PresPerf semantic configuration itself, the interpretation differences being associated with the various

temporal adverb specifications. My task is then basically to provide arguments establishing that in various constructions that contain the Perf form

RT cannot be () UT, but what is involved is rather RT < UT, which is

basically what PAST expresses. But before going on providing such arguments, I will sketch, for concreteness, a reasonable view of what Tenses

and Aspects are, although I will not address the details of the new developments of Tense and Aspect theories, the points to be made being neutral

with respect to any viable version of them.9

1.4.1. Aspects and tenses

As stated above, Reichenbachian (1947) terminology will be used. The

time denoted by a semantic tense is called reference time (= RT). Aktion-

76

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

sarten are located in time by means of a relation that connects RT to an

event time or event state (= ET), instantiating the Aktionsart. This relation

can be called an ASPECT relation, after Klein (1994). RT may INCLUDE

() ET in the ‘Perfective’, RT may be INCLUDED () in ET in the ‘Imperfective’, or RT may follow ET, being POST (>) in the ‘Perfect’. 10 Asp

relations, viewed as ‘temporalizers’, can be defined, after AvS (2002b), as

follows:11

(25) ASPECTS

a. ||PERFECTIVE|| = Pte.t (e) & P (e), P of type <v,t>

b. ||IMPERFECTIVE|| = Pte.t (e) & P (e)

c. ||PERFECT|| = Pte.t > (e) & P (e)

Elaborated definitions for TENSES are also provided by AvS (ibid), in line

with Partee’s (1973) reference tense theory, and Heim’s (1994) proposal

that tenses be viewed as restrictors of temporal variables:12

(26) TENSES

are symbols of type i which bear time variables as indices. Let c be

the context of the utterance, with tc the speech time, g is a variable

assignment, then

a. ||NOW||g,c is the speech time conceived as a point.

b. ||PASTj||g,c is defined only if g(j) precedes the speech time t c. If

defined, ||PASTj||g,c = g(j).

c. ||FUTRj||g,c is defined only if g(j) follows the speech time t c. If

defined, ||FUTRj||g,c = g(j).

These definitions (or simplified versions of them) will be adopted here,

except for Perf, which needs further elaboration in order to account for its

various meanings, but also its (usually) higher position in the tree architecture, compared to Pfv/Ipfv (which I take to be the core Asp opposition), in

conformity with (1).

As an illustration of the PAST/PERFECT contrast, consider (27). The latter can be interpreted as PAST, or PRESPERF, hence giving rise to the two

LF forms (28) and (29), respectively:

(27) sakan-a barliin-a.

lived-3 Berlin-acc

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

77

a. ‘He lived in Berlin’

b. ‘He has lived in Berlin.’

(28)

TP[PAST ASPP

[ PFV VP[He live in Berlin]]]

(29)

TP[NOW PERFP[be ASPP[ VP[He

live in Berlin]]]]

The representation (29) reflects the overall architecture of the system, in

which PerfP (or T2) is higher than AspP (which contains PFV). I have

introduced ‘be’ as a head of PerfP, although it is not realized. It could be

that this introduction is not necessary, and the ‘participle’ licenses both

PERF and PRES.13 If we follow AvS (ibid, fn. 16, p. 10), then PERF here

is an existential quantifier that introduces a time/event prior to RT. Its interpretation is as in (30):14

(30) t t < NOW & He lives in Berlin at t.

Note that the construction (27) can also have an extended-now (XN) interpretation, in fact a natural one. Consider the following variants of (27):

(27’)

a.

b.

sakan-a barliin-a

mund#u 1990.

lived-3 Berlin-acc since

1990

‘He has lived in Berlin since 1990.’

sakan-a barliin-a

xams-a marraat-in mund#u 1990.

lived-3 Berlin-acc five-acc times-gen since

1990

‘He has lived in Berlin five times since 1990.’

Like English since, mund#u can introduce a time span through , its complement, i.e. a position in time given by a date or some other temporal description. Mund#u modifies the XN introduced by Perf, and it indicates

that is the left boundary (LB) of XN. The construction (27b) is best analyzed as an XN-Perf, in this case an Existential Perf (E-Perf). The quantificational adverb xams-a marraat-in has to be confined within XN. The

meaning of the E-Perfect can be represented as follows:

(31) t XN (t, NOW) & LB (1990, t) & 5t’ t He live in Berlin at t'.

NOW is the meaning of the semantic PRES, the speech time conceived as a

moment. XN (t’,t) means that t is a final subinterval of t’. LB (1990,t’)

means that 1990 is LB of t’.

The construction (27a) can be interpreted as a Universal Perf (U-Perf).

The U-reading can be formulated as follows:15

(32) t XN (t, NOW) & LB (1990, t) & t’ t He live in Berlin at t'.

78

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

1.4.2. Positional ‘deictic’ adverbs

To disambiguate PAST and PRESPERF meanings, positional deictic adverbs can be used. The contrast is provided in (33) and (34), where past

and present adverbials are used. Note that the temporal morphology is not

compatible with future adverbs:

(33) katab-a r-risaalat-a

?amsi

wrote-3 the-letter-acc yesterday

‘He wrote the letter yesterday.’

(*g*ad-an).

(*tomorrow)

(34) katab-a r-risaalat-a

l-aan-a (*gad-an).

wrote-3 the-letter-acc now

(* tomorrow)

‘He has written the letter now (* tomorrow).’

The positional adverb diagnostic suggests that the adverb is taken to modify RT. It has been used for English successfully, at least since Jespersen

(1924). But this test appears to be disputable, once the behavior of PresPerf

in other languages is taken into account. Consider the following pair of

German examples (=(13a) and (14) of Löbner’s (2002)):

(35) Karla

ist

gestern

hier eingezogen.

Karla

is

yesterdayhere move-in

‘Karla (has) moved in here yesterday.’

(36) Jetzt,

now,

wo

where

Karla

Karla

gestern

hier eingezogen ist,

yesterdayhere move-in

is,

brauchen wir

need

we

einen

a

Schlüssel

key

fürs

for-the

Klo.

toilet

‘Now that Karla has moved in here yesterday, we need a key for the

toilet.’

The first construction is ambiguous between a Past reading and a PresPerfect reading. But the Perfect can have only a PRESPERF reading in (36),

although it combines with a past adverbial. This suggests that the adverb is

modifying the aspect phrase or some lower phrase, the VP (denoting ET).

Thus the compatibility of Perf with past and non-past time adverbials cannot count as an argument in favor of the ambiguity of the Perf, at least in

the German type languages (see Klein (1999) and Musan (2001), among

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

79

others, for arguments). If a similar reasoning were to extend to Arabic, then

we have to look for other diagnostics to establish the existence of a genuine PAST interpretation.

1.4.3. Perf and modal ‘qad’

The particle qad (meaning ‘already’, i.e. precedence, or ‘just’, immediate

precedence) is typically acknowledged in traditional literature to be collocating with Perf readings. For example, qad can occur immediately before

the ‘participle’ of a complex Perfect tense, as in (37):

(37) kaan-a qad

katab-a r-risaalat-a.

was

already wrote-3 the-letter-acc

‘He had already written the letter.’

It can also occur in front of a simple tensed verb, interpreted as PresPerf.

Thus in (38), qad can have one of the two precedence readings:

(38) qad

was8ala.

already/just arrived

a. He has already arrived.

b. He has just arrived.

But in (38), qad can be further ambiguous in a way that it cannot be in

(37). It can mean ‘indeed’, or ‘in fact’, to stress the factual certainty of the

event, and the sentence is translated as ‘He indeed came’ or ‘He did come’.

In the latter case, it serves as a modal. Modals are projected higher than

Tense (or T1). Unsurprisingly then, when qad serves as a modal, it takes

T1 projections as its complement, namely Past projections, co-occurring

with past time adverbials, as illustrated in (39):

(39) qad

was8al-a

?amsi.

indeed arrived-3

yesterday

‘He did arrive yesterday.’

Likewise, it takes also Present projections, as in (40), but the interpretation

is that of ‘possibility’ or ‘probability’, rather than certainty:

(40) qad y-as8il-u

may 3-arrive now

‘He may arrive now.’

The T1 nature of the complement of qad is further corroborated by its oc-

l-?aan-a.

80

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

currence in front of the auxiliary of a complex tense:

(41) qad

kaan-a y-us8allii.

indeed was

3-pray

‘He was indeed praying.’

The question now is the following: why can’t the complement of modal

qad in (39) be taken as Perf (or T2), instead of Past (or T1)? In other

words, what motivates restricting the selection of modal qad to T1? The

answer is straightforward. Consider the following minimal pair of constructions:

(42) kaan-a qad

was8al-a.

was-3 already arrived-3

‘He had already arrived.’

(43) qad

kaan-a was8al-a.

indeed was-3 arrived-3

‘He had indeed arrived.’

Both constructions are typically non-ambiguous. In (42), qad is only a Perfect Level specifier, and in (43) a Modal specifier. This absence of ambiguity is due to the fact that qad is unambiguously positioned, with respect to

T1 (Past), or T2 (Perf). In (38), the ambiguity arises due to ambiguity

placement. Note that no such ambiguity arises in (41), and (39) has at least

one reading in which it is a modal structure like (41), which implies that

Past, rather than PresPerf is involved there. Note in passing also that if

modal (39) were to be interpreted as Pres, then two problems arise. First,

we predict wrongly that the interpretation is ‘possibility’, rather than certainty. Second, qad would be selecting an empty auxiliary (or copula),

which it normally does not, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (44):

(44) *qad

r-rajul-u

musaafir-un.

may

the-man

travelling

Intended to mean: ‘The man may be traveling.’

In this case, the realization of the copula in the Pres form is obligatory (Cf.

Fassi Fehri (1993, 2000) for detail).

The particle Perf qad has a partly similar German counterpart. Schon, a

case of RT or PerfL specification, can be used with Past or with Perfect.

With the former, the interpretation is normally that the action only started,

or it is imperfective, but with the latter it is ambiguous. It has a PresPerf

meaning, with the action understood as completed, or it may have an inter-

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

81

pretation similar to that of Past imperfective. The examples (45) are from

Musan (2001, p. 363), and (46) is from Löbner (2002, pp. 386-7):16

(45) a. Er

he

b. Er

he

(46) Sie

she

hat

has

aß

ate

hat

has

schon

gegessen.

already eaten (= He finished his meal).

schon.

already (= He was already eating).

schon

gefrühstückt.

already have-breakfast

a. She has already had breakfast.

(Present Perfect)

b. She was already having breakfast. (Past Imperfective)

Likewise, qad interpretation differs depending on the temporal entity it

collocates with. When it means ‘already’, it is a Perf detector. When it is a

modal, it collocates with T1, meaning ‘indeed’ with Past, and ‘possible’ or

‘probable’ with Pres.17 Thus qad is uniformly a modal when it is higher

than T, and a Perf (or Asp) specifier otherwise. Its interpretation is then a

true diagnostic for helping us determining whether the Perf form is to be

interpreted as PAST or PERF.

1.4.4. Simple vs. complex tenses

Positional adverbs are known to be ambiguous with complex tenses (typically Perf tenses), because their structure allows for two positions that the

adverb can specify.18 For example, this ambiguity is found in (47), where

the letter could have been finished at four, or before four:

(47) kaana qad

?anhaa

r-risaalat-a

fii

r-raabicat-i.

was

already finished

the-letter-acc at

the-four-gen

‘He had already finished the letter at four.‘

Surprisingly, however, this ambiguity is not found with PresPerf, be it analytic, as in (48), or synthetic, as in (49):

(48) ?-akuunu

I-am

?anhay-tu r-risaalat-a

finished-I the-letter-acc

g*adan

fii

tomorrow-acc at

82

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

r-raabicat-i.

the-four-gen

‘I will have finished the letter tomorrow at four.’

(49) ?anhaa r-risaalat-a

(?amsi, l-?aan-a)

fii

r-raabicat-i.

finished the-letter-acc (yesterday, now)

at

the-four-gen

‘He (has) finished the letter (yesterday, now) at four.’

In (48), the adverb specifies only RT, i.e. the tense carried by the auxiliary.

In (49), read as PRESPERF, with a Now adverb, the same is true. The

problem arises with (49), when collocating with a past adverb. If (49) is

read as PRESPERF in this case, then the past adverbial has to be interpreted as specifying ET, contrary to what happens with other PresPerfs. If (49)

is read as PAST, no such a problem arises, because then the temporal Adv

would be modifying (uniformly) RT. Since the minimal hypothesis is to

assume a uniform RT specification, I will assume that this is the case, unless evidence is provided for the contrary. But note that if the tense were

PresPerf, then the (covert) auxiliary/copula denoting PRES would have to

be modified by the positional fii phrase. But such a possibility is independently excluded, as shown by the ungrammaticality of the following

PRES sentence:

(50) r-rajul-u

mariid8-un (*fii r-raabicat-i).

the-man-nom sick-nom (*at four)

‘The man is sick (*at four).’

Zero-Pres then appears to be not an option with a past adverbial, which

suggests in turn that the tense involved can only be PAST. If that is true,

then positional temporal adverbs play a role in T/A disambiguation, contrary to the conclusion reached in subsection 1.4.2, although not directly.19

1.4.5. Durational adverbs20

Indefinite temporal nominals can function as durational adverbials. They

are either complements of mund#u ‘since’, or they take (what looks like)

an accusative case. Call them mund#u-d and Acc-d, d for durative. The

two phrases do not distribute in the same way with tenses and aspects they

occur with, nor do they specify them in the same way.

Semantic PRES and PRESPERF are compatible with mund#u followed

by an indefinite complement:

(51) y-aktubu

r-risaalat-a

mund#u xams-i saacaat-in

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

3-write

the-letter-acc

since

five

83

hours

(l-?aana).

(now)

‘He is writing the letter since/for five hours (now).’

(52) katab-a r-risaalata

mund#u xamsi

saacaat-in

wrote-3 the-letter-acc since

five

hours

‘He has written the letter since five hours (now).’

(l-?aana).

(now)

But PAST does not combine with such adverbs:

(53) *kataba

wrote-3

r-risaalat-a

the-letter-acc

l-baarihat-a mund#u xamsi

yesterday since

five

saacaat-in.

hours

The advervial mund#u-d introduces an interval that reaches up to RT. But

RT has to be UT, basically NOW. If the adverb has RT,UT as its RB, then

its meaning is not compatible with that of Past (which is RT<UT). On the

other hand, if mund#u-d introduces an unbounded (homogeneous or nonquantized) interval, like seit-d in German (as proposed by AvS (2002)),

and if simple Past in Arabic is also PFV (as has been argued above), then it

follows that Past cannot be compatible with such an adverbial.

PRESPERF, however, is compatible with it, under various interpretations

that will be made clear below. Since the latter is PRES, it provides the appropriate RT for the adverbial RB. It can be PFV or IPFV, and hence allowing both homogeneous and non-homogeneous Ps as its complement.21

Semantic PAST combines, instead, with (indefinite) Acc-d, for example

when the predicate denotes an (atelic) activity:

(54) saafar-a

r-rajul-u

l-baarih8ata

travelled-3 the-man-nom yesterday five

‘The man traveled yesterday five hours.’

xamsa saacaat-in.

hours

But PRES cannot combine with Acc-d:

(55) *y-aakulu r-rajul-u

(l-?aan-a) xamsa saacaat-in.

3-eat

the-man-nom (now)

five

hours

The latter sentence is possible only with a habitual meaning (‘The man has

the habit now to eat for five hours’). The same contrast holds with statives:

84

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

(56) ?amsi

kaan-a r-rajul-u

yesterdaywas-3 the-man-nom

mariid8-an xamsa

sick-acc

five

saacaat-in.

hours

‘Yesterday, the man was sick for five hours.’

(57) *r-rajul-u

the-man-nom

mariid8-un xamsat-a ?ayyam-in.

sick-nom five

days

(58) *r-rajul-u

the-man-nom

musaafir-un

xamsat-a

travelling-nom five

?ayyam-in.

days

The latter construction is possible as a futurate, not PRES. The contrast

between PAST and PRESPERF is easier to detect with statives:

(59) ?amsi

kaan-a r-rajul-u

yesterdaywas-3 the-man-nom

jaalis-an,haziin-an

sitting-acc sad-acc

xams-a saacaat-in.

five

hours

‘Yesterday, the man was sitting, sad for five hours.’

(60) *kaan-a r-rajul-u

was-3 the-man-nom

jaalis-an,haziin-an l-?aana xamsa

sitting-acc

sad-acc

now

five

saacaat-in.

hours

These contrasts suggest that there is a genuine TENSE ambiguity of the

Past/Perf form. The latter can be PAST or PRES. If Acc-D is a quantizing

adverb, then PAST is compatible with it, since it is also PFV. Simple

PRES cannot combine with it because it is IPFV. As for stative

PRESPERF, it behaves like PRES in that it is also IPFV (and atelic).22

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

85

2. Temporal adverbs and kinds of Perfect

2.1.

Positional mund#u

We have seen that mund#u which takes an indefinite complement is interpreted as durational in the sense defined. Furthermore, mund#u-d is incompatible with Past. On the other hand, mund#u can take a definite complement. It then introduces not a length or duration, but rather a date or a

time span, which is the left boundary of an extended-now (XN) interval. I

will call it positional mund#u (following the terminological use of Musan

and AvS, among others), and refers to it as mund#u-t. Unlike mund#u-d,

mund#u-t appears to be compatible with all tenses. But in analyzing the

various interactions of mund#u-t with tense/aspect phrases, the PresPerf

appears to be specified in typical ways that make this adverbial a diagnostic test for distinguishing it from other tenses, typically PAST. These interactions also show the role played by Aktionsart and telicity.

2.1.1. Imperfective tenses

Consider first the case of atelic imperfective tenses, in their Pres and Past

versions, exemplified in the following pair of constructions:

(61) ?ajrii

mund#u r-raabicat-i.

I-run

since

four

‘I am running since/from four.’

(62) kun-tu ?ajrii

mund#u r-raabicat-i.

was-I

I-run

since

four

‘I was running since/from four.’

In (61), mund#u-t provides LB of RT, P is homogeneous, and RB is not

expressed, nor presupposed. The same is true of (62), although LB is situated in the Past. As for telic imperfectives, the interpretive situation does

not appear to be different. Consider e.g. the Present in (63):

(63) ?aktub-u r-risaalat-a

mund#u r-raabicat-I.

I-write the-letter-acc since

four

‘I am writing the letter since/from four.’

Like in (61), the LB of RT is specified by mund#u-t in (63), P is homogeneous, and RB is not expressed, nor presupposed. In sum, with imperfective temporal predicates, mund#u-t specifies uniformly LB (of RT), and RB

is not asserted, nor presupposed. Let us then call Ipfv-mund#u-t, and speci-

86

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

fy its meaning as follows:

(64) Ipfv-mund#u-t

||Ipfv-mund#u-t||(t) = Pt’t’[XN (t’,t’) & LB (t,t’) & P (t’)], P is

homogeneous.23

2.1.2. Perfective tenses

Consider now perfectives. Let us start with simple Past telics, the achievement (65) or the accomplishment (66):

(65) wajad-tu

found-I

l-h8all-a

the-solution-acc

l-baarih8at-a mund#u

yesterday since

r-raabicat-i.

four

‘I found the solution yesterday since four.’

(66) katab-tu

r-risaalat-a

l-baarih8at-a mund#u r-raabicat-i.

wrote-I

the-letter-acc yesterday since

four

‘I wrote the letter yesterday since four.’

In both (65) and (66), mund#u-t is interpreted as specifying the RB of the

Asp phrase, the point at which the event E culminates (in a telic perfective

situation). The solution is found by four, and the letter terminated by four.

LB is not expressed, but it is presupposed, and ‘pushed’ backwards into the

Past, so that the preparatory phase (including LB) takes place before four,

although it has to be located within yesterday.

The interpretive situation is not different (in relevant respects) for simple

Past atelics, exemplified in (67):

(67) ?akal-tu

l-baarih8at-a mund#u r-raabicat-i.

ate-I

yesterday since

four

‘I ate yesterday since four.’

In (67), mund#u-t modifies also the RB of the Aspect phrase, P is nonhomogeneous, and LB is not expressed, although it is presupposed. It has

to be some time in the Past, included in yesterday. Even in (67), the eating

has to take place at an interval which ends up at four, and the eating has

been taking place before four.

Complex perfectives behave in the same way as simplex ones. For ex-

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

87

ample, the complex form (68) behaves in the same way as its simplex

counterpart (66) in the relevant respects, namely the fact that the interpretation involves also RB specification:

(68) kun-tu

mund#u

was-I

qad

katab-tu r-risaalat-a

already wrote-I the-letter-acc

l-baarih8at-a

yesterday

since

r-raabicat-i.

four

‘I had already written the letter yesterday since four.’

These contrasts indicate that perfective tenses differ in their interaction

with mund#u-t, compared to imperfective tenses. With the former,

mund#u-t uniformly specify the RB of the AspP, its terminating point,

while with the latter they specify its LB. Call the adverbial Pfv-mund#u-t,

and let us specify its meaning as follows

(69)

Pfv-mund#u-t

||Pfv-mund#u-t||(t) = Pt’t’[XN (t’,t’) & RB (t,t’) & P (t’)], P is

non-homogeneous.

2.1.3. PresPref tense

Consider now the PresPerf interpretation of (66) above, and (70):

(70) jaray-tu mund#u r-raabicat-i.

ran-I

since

four

‘I have run since four.’

Both sentences can be read as either Ipfv or Pfv. In the first case, mund#u-t

specifies only the LB of the event, the starting point of writing the letter

(and the writing is not finished), or the beginning of the running (which is

not over). Perf then behaves like other imperfectives in that temporal P

must be homogeneous. To obtain the perfective interpretation, however,

the specification of the RB boundary is necessary. It is specified by the

nearest point in the past to Now. So the perfect aspect extends to Now, or it

is an XN, but it must be bounded (and P is non-homogeneous). But in both

Perf interpretations, mund#u-t specifies the LB of the AspP. This contrasts

significantly with the simple Past, in which only RB is specified. On this

base, mund#u-t specification can serve as a diagnostic test for distinguish-

88

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

ing PAST from PRESPERF.

Note that there is a case in which mund#u-t modifies the RB of a Perfect

situation, namely when it modifies the post-state (introduced by Perf).

Consider the following sentence:

(71) juc-tu

mund#u r-raabicat-i.

was-hungry-I since

four

‘I have become/been hungry since four.’

This sentence can have two interpretations: (a) I started being hungry since

four, and I am still hungry now (XN interpretation), or (b) I am hungry

since four, or I am in the post-state of being hungry since four. In the first

case, mund#u-t specifies the LB of the event, and in the second case, it

modifies the RB of the post-state. But this interpretation is not relevant for

the contrast with the Past, since the latter is not interpreted as denoting a

post-state. I return to this case in the next two subsections.

2.2.

Durational mund#u

As observed above, durative mund#u can co-occur with Ipfv and Perf tenses, but it cannot do so with simple Past. Consider again the following contrasts:

(72) maryam-u t-antad8#ir-u zaynab-a mund#u saacatayni.

Miryam

3f-wait

Zaynab

since

two hours

‘Miryam is waiting for Zaynab for two hours.’

(73) kaan-at maryam-u tantad8#ir-u zaynab-a mund#u saacatayni

was-3f Miryam

3f-wait

Zaynab

since

two hours

‘Miryam was waiting for Zaynab for two hours.’

(74) maryam-u ntad8#ar-at zaynab-a mund#u saacatayni.

Miryam

waited-3fZaynab

since

two hours

‘Miryam has waited for Zaynab for two hours.’

(75) *maryam-u

Miryam

ntad8#ar-at zaynab-a l-baarihat-a mund#u

waited-3fZaynab

yesterday since

saacatayni.

two hours

The sentences (72) and (73) show that Pres and Past Ipfvs can occur with

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

89

durational mund#u The latter then indicates that the event is positioned

two hours to the left of some point of reference, but its RB is not specified.

By contrast, the adverbial cannot occur with Past, which is Pfv, and hence

non-homogeneous. Consider now the following perfect sentence:

(76) maryam-u katab-at

r-risaalat-a

mund#u saacatayni.

Miryam

wrote-3f

the-letter-acc since

two hours

‘Miryam has written the letter since two hours.’

Why is (76) good even under a Pfv reading? The interpretation can be that

the adverbial is modifying a post-state, in which case the sentence would

behave like any stative sentence with respect to this modification. Then

what about eventive or PresPerf reading? The latter interpretation is also

possible, with mund#u-d specifying the LB of the duration, and NOW its

RB, i.e. RT would be the RB. That possibility is not open to Past, due to

the fact that its RT is located before Now, and hence cannot at the same

time abut Now. The semantics of the adverbial is then roughly as follows:

(77) Durative mund#u

||mund#u-d||(d) = Ptt’[XN (t’,t) & |t’| = d & P (t’)], P is homogeneous.

2.1.

Perf of Res and post-state

Resultative meaning of Arabic Perfect can be distinguished from that of

PERF or PAST. Comrie (1976, p.56) claims that ‘In the perfect of result, a

present state is reported as being the result of some past situation […] In an

answer to a question Is John here yet?, a perfectly reasonable reply would

be Yes, he has arrived, but not Yes, he arrived’. To that question, two potential answers in Arabic are the following:

(78) nacam was8al-a.

yes

arrived-3

‘Yes, he has arrived.’

(79) laa bal

g*aadara.

no

in fact left-3

‘No, he has in fact left.’

As Fleisch (1974) put it: “ce n’est plus seulement l’accompli, l’action conduite à son terme, mais l’action finie qui laisse quelque chose de réalisé: un

résultat”. This “result” may or may not be what Parsons (1990) calls re-

90

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

sultant state. It can be expressed through adjectival phrases, but I will limit

my investigation to verbal phrases, which are clearly in the Perf form. The

latter are normally translated by Pres forms in English or French:

(80) juc-tu.

became-hungry-I

(literally: ‘I hunger-ed’)

‘I am hungry/ J’ai faim.’

(81) s8adaq-ta.

were-right-you

(literally: ‘You right-ed’)

‘You are right/ Tu as raison.’

These sentences can obviously have Past or PresPerf readings, but the relevant reading we are interested in is the resultative one. One way to get the

latter reading is to think of the predicate as describing a kind of achievement, where the subject reaches the state of being hungry or being right.

Then the perfect phrase describes that state achieved. This could be a poststate. Resultatives can also be produced by passive perfect forms, such as

(82), or by anti-causative forms, such as (83):

(82) junn-a.

‘He got crazy.’

(83) n-kasara

l-ka?s-u.

anticaus-broke the-glass-nom

‘The glass got broken.’

For has been argued to modify a result state associated with a change of

state predicate. If Acc-d is the counterpart of for, then we expect it to serve

as a discriminating diagnostic for distinguishing predicates that have an

accessible resultant state from those that do not. The contrast is illustrated

by the following pair of examples:

(84) fatah8-tu

l-baab-a

saacatayni.

opened-I

the-door-acc two hours

‘have opened the door for two hours.’

(85) sallam-tu r-risaalat-a

(* saacatayni).

delivered-I the-letter-acc (* two hours)

Note that mund#u-d is not discriminatory in this respect:

(86) fatah8-tu

l-baab-a

mund#u saacatayni.

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

91

opened-I

the-door-acc since

two hours

‘I have opened the door since two hours.’

(87) sallam-tu r-risaalat-a

mund#u saacatayni.

delivered-I the-letter-acc since

two hours

‘I have delivered the letter since two hours.’

I postulate that Acc-d modifies a Perf of Res in the sense of Parsons

(1990), while mund#u-d modifies a post-state.

3. Summary and Conclusion

I am now in a position to be able to summarize: (a) what T/A verbal morphology contributes (ambiguously) to temporal meanings, (b) what contributions are made by adverb specifications, and finally (c) how the combinations of the two ingredients lead to disambiguation of T/A morphology

or T/A adverbials.

3.1.

T/A morphology

The picture that emerges from what has been discussed so far is as follows:

IPFV

PFV

XNPERF

PERF

RES

PRES

Pres

(Reporter’s) Pres

Past

Perf

Perf

PAST

Past Imperf

Past

Past Perf

Past Perf

Past Perf

FUT

Pres

Pres

Pres Perf

Pres Perf

Pres Perf

The following clarifications are in order. First, I have used Past/Pres, and

Perf/Imperf to designate the same T/A morphology, in order to be neutral

with respect to its interpretation, and also to facilitate the interpretation of

the table for the Indo-European reader. The use of only one pair of them

would obscure the picture. Second, designations with two separate terms

(e.g. Pres Perf) refer to analytic forms; the others are simple or synthetic.

Finally, I have omitted habituals, iteratives, generics, etc. from this table,

which does not pretend to be exhaustive.

3.2.

T/A adverbs or particles

92

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

Consider first the particle qad. As observed above, it can be a Perf detector

(or a Perfect level specifier; = PL), or a Tense detector, when it is a modal

level (ML). The opposition addressed here is between PresPerf and Past:

qad

PL

ML

PAST

PERF

+

+

Consider now mund#u (= mun henceforth). Mun-t and mun-d will be treated separately:

(a) Mun-t:

As was clarified above, the main distinctive feature of mun-t is whether it

specifies RB or LB of RT or of the Perfect construction (PL). An stands

here for analytic or complex forms, and Sy for synthetic or simple forms:

Mun-t

IPFV

PFV

PRES

LB

RB

PAST

An: LB

Sy: RB

PERF

LB

RB

XNPERF

LB

LB & RB

RES

RB/PL

(b) Mun-d:

Mun-d

IPFV

IPFV

3.3.

PRES

+

PAST

+

*

PERF

+

+

POST-S

+

+

Conclusion

We have seen how the form of the simple Past expresses not only PAST,

but also various meanings of PresPerf, including PRESPERF, XNPERF,

POSTSTATE or RESPERF, but not FUTPERF. On the other hand, analytic PresPerf expresses FUTPERF (among other meanings, which I have not

fully investigated here), but not PRESPERF. Temporal adverbs and particles have been shown to be just as ambiguous as T/A morphology, but they

are T/A dependent, and hence can be disambiguated depending on the temporal context. I have examined the distribution and interpretation behavior

of qad, which is ambiguously PL or ML, but which becomes unambiguous

in appropriate syntactic configurations. Likewise, a durational/positional

distinction has been postulated to account for the behavior of mund#u.

Mund#u-t turns out to behave differently depending on whether it collocates with PFV or IPFV tenses. With the former, it specifies the RB of the

time span it introduces, but with the latter it specifies its LB. Furthermore,

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

93

PAST and PRESPERF collocating with this adverbial are clearly distinguishable. On the other hand, mund#u-d excludes Perfective tenses, and

hence PAST, which is associated with PFV. But Imperfective PRESPERF

collocates with the latter adverb, just as PRES does. Finally, Acc-d adverbs

have been shown to be combinable with PAST, but not PRES or Imperfective PRESPERF, and they serve as a diagnostic for identifying change of

state predicates having a resultant state. It is expected that this dual description of T/A morphology and temporal adverb specifications will prove

to be more promising for capturing how languages express TR than a single dimension description.

Notes

1. This study elaborates on previous work of mine (cf. Fassi Fehri (2001, 2000), as

well as (1993)). It is particularly influenced by Arnim von Stechow’s (2002;

=AvS) work on the semantics of the Perfect and typically the German seit.

2. This methodology is currently becoming popular among linguists. For example,

AvS (2002, p.1)) adopts the view that progress can be made “… only by a careful investigation of the meanings of temporal adverbials and by stating their

formal semantics in a way which is precise enough to test empirical predictions”.

3. Arabic verbo-temporal morphology contrasts two finite forms characterized by

Person placement (as a suffix for Past, and prefix for non-Past or Pres), internal

vocalic changes of the verb stem, and (suffixed) Mood marking in the Pres (and

its absence in the Past). These forms contribute to mark Mood, T, and Asp interactions. See Fassi Fehri (1996) for detail.

4. See Giorgi & Pianesi (1997) as well as Schmitt (2001) for different analyses of

the Portuguese Perf.

5. Cf. Ogihara (1995) and Abusch (1997), among others. Cf. also Higginbotham’s

(2000a) analysis of SOT, based on anaphoricity.

6. The Arabic stative counterpart to (18) read as anaphoric is (i), where no copula

surfaces:

(i) qaal-a

l-ii

?inna-hu

mariid-un.

said-3

to-me

that-him

sick

‘He said to me that he is sick.’

When the past copula is used, no “present-under-past” reading is possible:

(ii) qaal-a

l-ii

?inna-hu

kaan-a mariid-an.

said-3

to-me

that-him

was-3

sick-acc

‘He said to me that he was sick.’

7. Compare their examples (17) and (21), p. 349.

8. GP (2001), who analyze quite similar contrasts in Italian, reach a similar conclusion. Italian simple Past and Perfect are Perfective, and they contrast with

94

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

Past Imperfect, which is Imperfective. The former tenses cannot be extended

(unless the interpretation is different, as indicated). See e.g. the contrasts in their

examples (22) and (23).

9. If we follow e.g. Klein (1994, 1999), then Perf is treated as Asp, on a par with

Pfv, although Perf is normally higher in structure than Pfv, as in English John

has been eating an apple. In other theories, it is treated as “relative tense” in the

sense of Comrie (1985), or T2 (cf. e.g. Giorgi & Pianesi (1997)). In such a case,

two Rs can be postulated, R1 and R2, as proposed explicitly in Cinque (1999),

following an approach initiated by Sten Vikner (1985). The two Rs approach

has various advantages, among which is the fact that it makes room for the representation of the future perfect of the past (as in He would have worked). That

approached is implicitly adopted here, although details will not be addressed. I

will only place Perf here as higher than Pfv (the genuine Asp). Cf. Cinque

(1999) for crosslinguistic motivation, as well as Fassi Fehri (2000 & 2001) for

justification in Arabic grammar.

10. Klein’s (1994) aspectual relations can be simplified as follows:

- RT (= his TT, or Topic Time) is a subinterval of ET, or is (properly) included in it;

- RT contains ET;

- RT follows ET;

- RT precedes ET.

11. e is an event or a state; (e) is the time of e, i.e. the interval from the beginning

of e till the end of e; v is the type of events, i that of states.

12. Simple definitions are provided e.g. by Klein (1994):

(i)

PAST: (some subinterval of) RT is BEFORE UT;

(ii)

FUTURE: RT is AFTER UT;

(iii) PRESENT: RT is SIMULTANEOUS TO, or CONTAINS UT.

13. Note that the “participle” of the thematic verb may be taken as the source for

licensing PRES, PERF, and even PFV when the PresPerf is interpreted as

such. This observation is based on the fact that the sole auxiliary “be” is not

selective, and has presumably no “Perf content”, unlike what has been proposed for “have”. See Wunderlich (1997) for a quite illuminating discussion

on the contributions of auxiliaries and participles to temporal meanings, depending on crosslinguistic lexical differences.

14. AvS claims that this is the simplest analysis, going back at least to Prior

(1967). Cf. the reference there.

15. For the U/E distinction of Perfects, see McCawley (1971), McCoard (1978),

Dowty (1979), Mittwoch (1988), Vlach (1993), among others. Iatridou, Anagnostopoulo, & Izvorski (2001) provide formulations of the two readings and

their paraphrases, which if applied to this example, read as follows:

U-reading

(i) a. There is a time span (Perftsp) whose LB is in 1990 and whose RB is

UT, and throughout that tsp He lives in Berlin.

b. i (LB = 1990) & RB = Now & t i (Ev (t))).

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

95

E-reading

(ii) a. There is a tsp (Perftsp) whose LB is in 1990 and whose RB is UT,

and in that tsp is an ev of his living in Berlin.

b. i (LB = 1990) & RB = Now & t i (Ev (t))).

On further refinements, as well as a characterization of English “since”, see

Von Fintel & Iatridou (2002).

Musan attributes her examples to Wolfgang Klein (p.c.). Her analysis of the

PresPerf differs obviously from Löbner’s, who argues that the tense semantics

of the latter is not uniformly PRES (Perf), but can be PAST (non-Perf) as

well.

See Fassi Fehri (1993) for detail.

The two positions are normally taken to be ET or RT, but they could be two

RTs, as pointed out in fn. 9 above. I will assume the latter approach, which

takes into account the “tense” dimension of Perf.

Note that the ambiguity problem appears to be solved differently in languages

having a general analytic Perf, such as German or French. Musan (2001), for

example, who discusses similar facts in German, acknowledges an asymmetrical behavior of adverbs with PresPerf: Pres and Fut Advs target RT, whereas

Past Advs target only ET. But this limitation of the Past Adv to ET is not motivated in view of the data discussed by Löbner (2002), on the one hand, and

the RT level of Past Advs occurring with PAST, on the other hand.

For a discussion of the behavior of such adverbs in other languages see the

articles of Arosio, Rathert, Giannakidou, Veloudis and Iatridou et al. in this

volume.

Constructions like (i) are also interpreted as PresPerf:

(i) qul-tu

haad#aa mund#u

zamanin

tawiil-in.

said-I

this

since

time

long

‘I have said this a long time ago.’

Note that PAST is compatible with mund#u taking definite complements, but

these cases are analyzed differently, as positional adverbs, which introduce a

time span located somewhere in the past. See subsection 2.1 below.

Comparable facts in Italian have been reported to me by Fabrizio Arozio. Per

adverbials are only compatible with Passato Remoto (PAST PFV), but not

with Pres or Imperf. Acc-D is then like Per. The incompatibility of PAST and

mund#u -d also resembles in part the behavior of Italian da: da can occur with

Pres and Imperf, but not with Passato Remoto. Cf. also Giorgi & Pianesi

(2001) for relevant discussion. Note that the PresPerf behavior with Acc-d depends on Aktionsart. See below subsection 2.1.3.

P is homogeneous if it has the subinterval property, i.e., for any t and t’, if t’ is

a subinterval of t and P is true of t, then P is true of t’ as well.

References

96

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

Abusch, Dorit

1997

Sequence of Tense and Temporal de re. Linguistics & Philosophy

20: 1-50.

Chomsky, Noam

1995

The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo

1999

Adverbs and functional heads. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, D.

1989

L’aspect verbal. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Cohen M.

1924

Le système verbal sémitique et l’expression du temps. Paris:

Leroux.

Comrie, Bernard

1976

Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1985

Tense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dowty, David

1979

Word Meaning and Montague Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Eisle, J. C.

1990

Time reference, Tense, and Formal Aspect in Cairene Arabic. In

Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics 1, M. Eid (ed.), 173-212. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Enç, Mürvet

1987

Anchoring Conditions for Tense. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 633-657.

Fassi Fehri, A.

1993

Issues in the Structure of Arabic Clauses and Words. Dordrecht:

Kluwer Academic Publishers.

1996

Distributing features and affixes in Arabic Subject Verb Agreement Paradigms. Linguistic Research 1.2: 1-30. Rabat: IERA.

2000

How aspectual is Arabic? Paper presented at the Paris Roundtable

on Tense and Aspect. To appear in J. Guéron and J. Lecarme (eds.)

The Syntax of Time. Cambridge: MIT Press.

2001

Synthetic/Analytic Asymmetries in Voice and Temporal Patterns.

Linguistic Research 6.2: 11-56. Rabat: IERA.

Fleisch, H.

1974

Sur l’aspect dans le verbe en arabe classique. Arabica XXI: 11-19.

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

97

Giorgi, Alessadra, and Fabio Pianesi

1995

From Semantics to Morphosyntax: The case of the Imperfect. In

Temporal Reference, Aspect and Actionality, P.M. Bertinetto, V.

Bianchi, J. Higginbotham, & M. Squartini (eds.), 1, 341-363. New

York: Rosenberg & Sellier.

1997

Tense and Aspect. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2001

Ways of Terminating. In Semantic Interfaces, C. Cecchetto, G.

Chierchia and M.T. Guasti (eds), 211-277. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Guéron, Jacqueline

1995

Chaînes temporelles simples et structures auxiliaires. In Rencontres:

Etudes de syntaxe et de morphologie, P. Bouchet et al. (eds.), 43-77.

Paris: Univ. de Paris X Nanterre.

Heim, Irene

1994

Comments on Abusch’s theory of tense. Ms. Cambridge, Mass:

MIT.

Higginbotham, James

2000a

Why Sequence of Tense Obligatory? ms. USC.

2000b

On the Expression of Tense and Aspect: The Case of the Progressive.

Paper presented at the Paris Roundtable on Tense and Aspect. To

appear in J. Guéron and J. Lecarme (eds.) The Syntax of Time. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hornstein, Norbert

1990

As Time Goes By. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Iatridou, Sabine, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Roumyana Izvorski

2001

Observations about the Form and Meaning of the Perfect. In Ken

Hale: A life in Language, M. Kenstowicz (ed.), 189-238. Cambridge,

Mass: MIT Press. (reprinted in this volume)

Kayne, Richard

2000

Parameters and Universals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Klein, Wolfgang

1992

The present perfect puzzle. Language 68: 525-552.

1994

Time in Language. London: Routledge.

1999

Wie sich das deutsche Perfekt zusammensetzt. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 113: 52-85.

Kratzer, Angelika

2000

Building Statives. Paper presented at the Berkeley Linguistic Society

Meeting 26.

Kurylowicz, J.

1972

Studies in Semitic grammar and Metrics. London: Curzon Press.

1973

Verbal aspect in Semitic. Orientalia 42: 114-120.

98

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

Löbner, Sebastian

2002

Is the German Perfekt a perfect perfect? To appear in Studia Grammatica.

Meillet, A.

1910

De l’expression du temps. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de

Paris XX.2: 137-141.

McCawley, James

1971

Tense and time reference in English. In Studies in linguistic semantics, Charles Fillmore and Donald Langendoen (eds.), 96-113. New

York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

McCoard, Robert W.

1978

The English Perfect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Mittwoch, Anita

1988

Aspects of English aspect. Linguistics and Philosophy 11: 203-254.

Musan, Renate

2000

The Semantics of Perfect Constructions and Temporal Adverbials in

German. Habilitationsschrift. Berlin: Humboldt Universität.

2001

The Present Perfect construction in German: Outline of its semantic

composition. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19: 355-401.

2002

Seit-Adverbials in Perfect Constructions. Ms. Berlin: Humboldt Universität. (in this volume)

Ogihara, Toshiro

1995

Tense, Attitudes, and Scope. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Paslawska, A. and A. von Stechow

2002

Perfect in Russian and Ukrainian. Ms. Univ. of Tübingen. (in this

volume)

Parsons, Terence

1990

Events in the semantics of English. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Partee, Barbara

1973

Some Structural Analogies between Tenses and Pronouns in English

Journal of Philosophy 70: 601-609.

1984

Nominal and temporal anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy 7: 243286.

Reckendorf, H.

1895

Die syntaktischen Verhältnisse des Arabischen. Leiden.

Reichenbach, Hans

1947

Elements of Symbolic Logic. New York: The Free Press.

Schmitt, C.

2001

Cross-linguistic variation and the Present Perfect: The case of Portuguese. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19: 403-453.

Sibawayhi, A. (8th century)

1938

al-kitaab. Cairo: Buulaaq

Arabic perfect and temporal adverbs

99

Stowell, Tim

1993

The Syntax of Tense. Ms. UCLA

Szemerényi, O.

1965

Unorthodox views of tense and aspect. Archivum Linguisticum 17:

161-171.

Vikner, Sten

1985

Reichenbach revisited: one, two or three temporal relations. Acta

Linguistica Hafniensia 19: 81-98.

Vlach, Frank

1993

Temporal adverbials, tenses, and the perfect. Linguistics and Philosophy 16: 231-283.

von Fintel, Kai, and Sabine Iatridou.

Since since. Ms. Cambridge, Mass: MIT.

von Stechow, Aarnim

2002

German seit “since“ and the ambiguity of the German perfect. Ms.

Univ. of Tübingen.

Wright, W.

1898

A Grammar of the Arabic Language. Translation from Caspari, with

edition, corrections and additions. Third edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wunderlich, Dieter

1997

Participle, Perfect, and Passive in German. Theorie des Lexikons

Grammatica 99.

2001

Prelexical Syntax and the Voice Hypothesis. Studia Grammatica 52:

487-513.

Zagona, K.

1990

Times as Temporal Argument Structure. Ms. Univ. of Washington.

100

Abdelkader Fassi Fehri

A

Aspect

imperfective 71, 72–75, 76

perfect 76

perfective 71, 72–75, 76

L

Löbner, Sebastian 78

M

Musan, Renate 72

C

Comrie, Bernard 89

D

durative adverbs

mund#u ('since') 77, 82, 85, 88

E

existential Perfect 77

F

frequency adverbs

xams-a marraat-in ('five times') 77

futurate temporal adverbs 71

G

Giorgi, Alessandra 74

H

Heim, Irene 76

K

Klein, Wolfgang 76

P

Parsons, Terence 91

Partee, Barbara 76

Perfect

Extended-Now-Theory 77

futurate 71

in Arabic 71–72

in German 72

in Portugese 72

of result 90

Pianesi, Fabio 74

positional adverbs

tomorrow 78–79

yesterday 78–79

post-state 88, 89, 90, 91

R

Reichenbach, Hans 75, 76

resultant states 90

S

sequence-of-tense (SOT)

in Arabic 73

in English 73

Stechow, Arnim von 83

U

universal Perfect 77