Unit Assessment Keyed for Instructors

advertisement

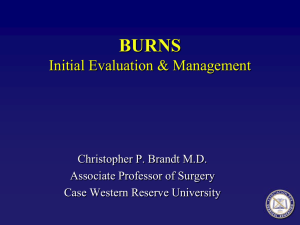

Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns Chapter 32 Burns Unit Summary Although you probably won’t see moderate or severe burn on a daily basis, you will encounter some serious thermal burn injuries during your career, and you might encounter serious electrical, chemical, and radiation injuries as well. Accurate recognition of the severity of burn injuries can dramatically enhance the care of burned patients by allowing you to institute proper emergency care. It is important to understand the treatment for burn shock. In addition, contacting the receiving facility en route will allow burn specialists to provide triage over the phone and will allow them to prepare for the incoming patient. National EMS Education Standard Competencies Trauma Integrates assessment findings with principles of epidemiology and pathophysiology to formulate a field impression to implement a comprehensive treatment/disposition plan for an acutely injured patient. Soft-Tissue Trauma Recognition and management of • Wounds (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) • Burns – Electrical (pp 1595-1597) – Chemical (pp 1590-1595) – Thermal (pp 1578-1579; 1590) • Chemicals in the eye and on the skin (pp 1590-1595) Pathophysiology, assessment, and management of • Wounds – Avulsions (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) – Bite wounds (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) – Lacerations (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) – Puncture wounds (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) – Incisions (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) • Burns – Electrical (pp 1595-1597) – Chemical (pp 1590-1595) – Thermal (pp 1578-1579; 1590) – Radiation (pp 1599-1600) © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 1 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns • High-pressure injection (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) • Crush syndrome (see chapter, Soft-Tissue Trauma) Knowledge Objectives 1. Describe the anatomy and physiology of the skin, including the layers of the skin. (pp 1575-1577) 2. Describe the anatomy of the surface of the eye. (p 1577) 3. Summarize the general pathophysiology of burn injury. (pp 1577-1581) 4. Describe five types of thermal burns. (pp 1578-1579) 5. Discuss the symptoms of burn shock. (pp 1577-1578) 6. Identify some of the warning signs of intentional burns associated with the potential abuse of children, elders, and people with disabilities. (pp 1578-1579) 7. Define and describe the characteristics of superficial, partial-thickness, and full-thickness burns. (pp 1579-1580) 8. Describe the pathophysiology of inhalation burns. (pp 1580-1581) 9. Summarize the safety concerns that must be addressed during the size-up of a burn scene. (pp 1582-1583) 10. Summarize the primary and secondary assessment processes for a burn patient. (pp 15831586) 11. Compare three different methods for determining burn severity. (p 1584) 12. Contrast the burn severity classification for infants and children with that for adults. (pp 1584–1586) 13. List the referral criteria for transporting a patient to a burn unit. (pp 1584-1586) 14. Discuss emergency medical care of a patient with a burn injury, including specific airway management techniques, fluid resuscitation techniques, and pain management. (pp 15861589) 15. State the Consensus formula, and discuss its use as it pertains to the prehospital environment, including types of solutions to use and amounts to administer during the prehospital phase. (pp 1588-1589) 16. Describe the management of thermal burns, including the use of sterile dressings. (p 1590) 17. Describe the management of burn shock. (pp 1589-1590) 18. Describe the management of inhalation burns. (p 1590) 19. Describe the pathophysiology, assessment, and management of chemical burns of the skin and eye. (pp 1590-1595) 20. Describe the pathophysiology, assessment, and management of electrical burns. (pp © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 2 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns 1595-1597) 21. Describe the pathophysiology, assessment, and management of radiation burns. (pp 15991600) 22. Discuss the special considerations involved in the treatment of pediatric and geriatric patients. (p 1600) 23. Summarize some of the long-term consequences of burn injury on the patient’s quality of life and on the paramedic’s psychological well-being. (p 1601) Skills Objectives 1. Demonstrate how to care for a burn. (pp 1586-1590) 2. Demonstrate the emergency medical care of a patient with a thermal burn. (p 1590) 3. Demonstrate the emergency medical care of a patient with an inhalation burn. (p 1593) 4. Demonstrate the emergency medical care of a patient with a chemical burn. (pp 15901595) 5. Demonstrate the emergency medical care of a patient with an electrical burn. (pp 15951597) 6. Demonstrate the emergency medical care of a patient with a radiation burn. (pp 15991600) Readings and Preparation Review all instructional materials including Chapter 32 of Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition, and all related presentation support materials. See enhancements below for more readings. Support Materials • Lecture PowerPoint presentation • Case Study PowerPoint presentation Enhancements • Direct students to visit the companion website to Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition, at http://www.paramedic.emszone.com for online activities. • The National Institutes of Health has abundant information on burn patients. You may access it from this link: http://www.nih.gov • Another valuable link is the American Burn Association: http://www.ameriburn.org • International information can be found at http://www.worldburn.org/links.asp Content connections: Review anatomy, physiology and topigraphical terms as necessary. Teaching Tips © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 3 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns Burns are one of the most feared types of injury. There is a definite emotional factor that you will need to overcome through your presentation. There are abundant pictures throughout the chapter that you may use to open a discussion of treating the entire patient, not just the obvious injury. Unit Activities Writing activities: Direct students to research the closest burn center to their class location. Students should include demographic information and internal census counts. Students should include local protocols for prehospital burn treatment as well as how patients could be transported to the closest burn unit. Student presentations: Students may present the results of their writing assignment or group activity Group activities: Have students research various methods of burn patient rehabilitation. Students should include other effects such as mental, psychological, family factors, etc. Students should locate the closest burn rehabilitation center to their class location. Visual thinking: Provide students with blank whole body anatomical diagrams. Read a scenario to the class that involves burn patients. Describe the location and size of the burns verbally. Students should diagram their impression of the location and size based only on your verbal description. This will demonstrate the difficulty in judging injury as well as how to convey this information to the receiving hospital. Medical terminology: Pre-Lecture You are the Medic “You are the Medic” is a progressive case study that encourages critical-thinking skills. Instructor Directions Direct students to read the “You are the Medic” scenario found throughout Chapter 32. • You may wish to assign students to a partner or a group. Direct them to review the discussion questions at the end of the scenario and prepare a response to each question. Facilitate a class dialogue centered on the discussion questions and the Patient Care Report. • You may also use this as an individual activity and ask students to turn in their comments on a separate piece of paper. Lecture I. Introduction A. Approximately 80% of all civilian fire-related deaths occur in residential constructions. 1. Burn injuries and death in the United States have decreased due to: a. Stricter building codes b. Use of smoke detectors 2. Children younger than 5 years and elderly people are at higher risk. 3. The ability to treat large burns has improved due to: © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 4 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns a. b. c. d. e. Better understanding of “burn shock” Advances in the use of fluid therapy and antibiotics Improved ability to excise dead tissue Use of biologic dressings to aid early wound closure The formation of specialized teams to treat patients B. Deaths and injuries also occur from electrical and chemical burns. 1. Accurate recognition of the severity of injuries can enhance the care of patients. 2. Contacting the receiving facility en route will allow burn specialists to provide triage over the phone and prepare for the patient. II. Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin A. The human skin has a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis within the body. 1. The skin is usually able to repair itself. 2. The skin has four functions: a. Protect the underlying tissue from injury and exposure to: i. Extreme temperature ii. Ultraviolet radiation iii. Mechanical forces iv. Toxic chemicals v. Invading microorganisms b. Aid in temperature regulation. c. Prevent excessive loss of water from the body and drying of tissues. d. Keep the brain informed about the external environment. i. Changes in temperature and sensations of pain are mediated through sense receptors. 3. People who survive serious burns may have: a. b. c. d. Difficulty with thermoregulation Inability to sweat from the scarred portions of the skin Impaired vasoconstriction and vasodilation in the areas of damage Little or no melanin in the scar tissue i. Makes the skin susceptible to sunburn e. Inability to grow hair on the injured site f. Little or no sensation in the scarred areas B. Layers of the skin 1. The skin is composed of two principal layers: a. Epidermis (outermost layer) i. Body’s first line of defense ii. Major barrier against water, dust, microorganisms, and mechanical stress iii. Composed of several layers © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 5 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns (a) Outermost layer of hardened, nonliving cells (b) Three inner layers of living cells b. Dermis (inner layer) i. Composed of collagen fibers, elastin fibers, and a mucopolysaccharide gel (a) Collagen gives the skin high resistance to breakage under mechanical stress. (b) Elastin allows the skin to spring back to its usual contours. (c) The mucopolysaccharide gel gives the skin resistance to compression. 2. Enclosed within the dermis are several structures. a. Nerve endings mediate the senses of touch, temperature, pressure, and pain. b. Blood vessels carry oxygen and nutrients to the skin and remove carbon dioxide and metabolic waste products. c. Sweat glands produce sweat and discharge it through ducts passing to the surface of the skin. i. The average volume of sweat lost during 24 hours ranges from 500 to 1,000 mL. d. Hair follicles produce hair and enclose the hair roots. i. At the neck of each hair follicle is a sebaceous gland that produces an oily substance called sebum. (a) Believed to keep the skin supple so it doesn’t dry out and crack 3. The tissue beneath the dermis is called the subcutaneous layer. a. Consists mainly of adipose tissue (fat) i. Insulates the underlying tissues from extremes of heat and cold. ii. Provides a cushion for underlying structures iii. Serves as an energy reserve for the body 4. Beneath the subcutaneous layer are the muscles, tendons, bones, and vital organs. C. The eye 1. Sensitive to burn injuries 2. Tear ducts and eyelids constantly lubricate the surface of the eyes. a. Intense heat, light, or chemical reactions can burn the thin membrane covering the surface of the eye. i. The higher the pH of the substance, the more severe the damage to the eye. ii. Damage is worsened by rubbing the eyes as opposed to initiating irrigation. III. Pathophysiology A. Burns are soft-tissue injuries created by destructive energy transfer via radiation, thermal, or electrical energy. 1. When a person is burned and the skin is damaged, the victim becomes at risk for: a. b. c. d. Infection Hypothermia Hypovolemia Shock © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 6 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns B. Burn shock 1. Occurs because of two types of injury: a. Fluid loss across damaged skin b. Series of volume shifts within the rest of the body 2. Intravascular volume oozes into the interstitial spaces. a. Cells of normal tissues take in increased amounts of salt and water from the fluid around them. b. As blood pressure falls, tachycardia and vasoconstriction occurs. c. Chemical mediators are released, possibly causing additional damage. d. Coagulation disorders may cause excessive bleeding. 3. Involves the entire body a. Limits the distribution of oxygen and glucose to the tissues b. Hampers the circulation’s ability to remove waste products from tissues. 4. Adequate fluid resuscitation is essential. C. Thermal burns 1. Can occur when skin is exposed to temperatures higher than 111°F (44°C) a. Can also occur when the heat absorbed exceeds the tissue’s capacity to dissipate it 2. Severity correlates with: a. Temperature, concentration, or amount of heat energy possessed by the object or substance b. Duration of exposure 3. Severity can also be affected by: a. Age of the patient b. Thickness of the skin c. Concomitant injuries and preexisting medical conditions 4. Heat energy can be transmitted in a variety of ways: a. Flame burns i. Most common ii. Often a deep burn iii. May also be associated with inhalation injuries b. Scald burns i. Produced by hot liquids ii. Often cover large surface areas because liquids can spread quickly iii. About 100,000 scald burns result annually from spilled food and beverages. c. Contact burns i. Produced by coming in contact with hot objects ii. Rarely deep because reflexes normally protect a person from prolonged exposure © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 7 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns iii. May be a sign of abuse in children, older people, and people with disabilities, especially if: (a) Formed shape or unusual pattern (b) Found in atypical places such as the genitalia, buttocks, and thighs d. Steam burns i. Can produce a topical scald burn ii. Common when peeling away plastic wrap covering microwaved food iii. Can cause significant injury to the lower airway e. Flash burns i. A relatively rare source of thermal burns ii. Produced by an explosion (a) Injuries are usually minor compared with the potential for trauma from whatever caused the flash. D. Burn depth 1. A burn wound is categorized by the degree of injury. 2. Described by three pathologic progressions or zones a. Zone of coagulation i. Skin nearest the heat source, suffering the most profound cellular changes ii. There is little or no blood flow to this area. b. Zone of stasis i. The area surrounding the zone of coagulation ii. Has decreased blood flow and inflammation iii. May undergo necrosis within 24 to 48 hours after the injury c. Zone of hyperemia i. In this area, cells will typically recover in 7 to 10 days. 3. The role of treatment is to salvage as much of the injured tissue as possible by: a. Improving perfusion b. Limiting the secondary changes that turn damaged tissue into dead tissue 4. Burn depth is categorized by severity—first, second, and third degree. a. Paramedics should limit their assessment to superficial, partial-thickness, and full-thickness burns. i. Simplifies the process ii. Avoids confusion and miscommunication 5. Superficial burns a. Involves the epidermis only b. Skin is red and swollen. i. When touched, the color will blanch and return. c. Patients will experience pain because nerve endings are exposed. d. Will heal spontaneously in 3 to 7 days © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 8 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns e. The most common example is a sunburn. 6. Partial-thickness burns a. Involves the epidermis and varying degrees of the dermis b. Can be subdivided into: i. Moderate partial-thickness burn (a) Skin is red. (1) When touched, the color will blanch and return. (b) Blisters or moisture are present. (c) The patient may experience extreme pain. (d) Hair follicles remain intact. (e) Will typically heal spontaneously but may scar or have a changed appearance ii. Deep partial-thickness burn (a) Extends into the dermis (b) Damages the hair follicle and sweat and sebaceous glands c. May be difficult to delineate between the two in the field 7. Full-thickness burns a. b. c. d. e. f. Involves destruction of both layers of the skin The skin is incapable of self-regeneration. The skin may appear white and waxy, brown and leathery, or charred. No capillary refill occurs. Sensory nerves are destroyed. i. There may be no pain in the full-thickness section, but significant pain in the surrounding areas. Treatment will often require skin grafting. E. Inhalation burns and intoxication 1. Inhalation burns can cause serious airway compromise. a. The lungs and the airway can be irritated by heat and/or toxic chemicals. i. Damage to the vocal cords, larynx, and lower airway is often associated with steam or hot particulate matter. ii. Damage to the upper airway is often associated with superheated gases. 2. Smoke inhalation a. The majority of deaths from fires are from inhalation of toxic gases, upper airway compromise, or pulmonary injury. i. Fire fighters protect themselves by wearing self-contained breathing apparatus. b. Anyone who is exposed to smoke from a fire may experience: i. Thermal burns to the airway ii. Hypoxia from lack of oxygen iii. Tissue damage and toxic effects caused by chemicals in the smoke 3. Carbon monoxide intoxication a. Carbon monoxide (CO) evolves from incomplete combustion of carbon compounds. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 9 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns b. c. d. e. i. The less efficient the combustion process, the more toxic the gases that may be created. ii. May be emitted when furnaces, kerosene heaters, and other heating devices are in poor repair iii. May also be emitted by internal combustion engines (a) Should always have their exhaust vented to the outdoors iv. Methylene chloride, which is used as an industrial solvent, is metabolized to CO by the body. CO can displace oxygen (O2) from the alveolar air and the blood hemoglobin. i. Binds to receptor sites at least 250 times more easily than O2 Being exposed to relatively small concentrations will result in progressively higher blood levels of CO. i. Levels of 50% or higher may be fatal. CO intoxication should be considered when: i. A group of people in the same place all complain of headache or nausea. ii. People complain of feeling sick at home but not when they go to work or school. Patients with severe CO intoxication usually present with an O2 saturation of normal or better. i. Never trust a pulse oximeter. IV. Patient Assessment A. Burns can fool paramedics, because victims may not act sick. 1. The severity of the injuries may not become apparent until you complete your assessment. 2. Initially stable conditions may be deemed more serious after careful evaluation at the hospital. a. The progression of burn-related pathology continues after the initial incident. b. Maintain a high index of suspicion even when injuries do not initially seem severe. c. Seriously burned patients may need to be transferred from tertiary facilities to larger burn centers. 3. It is important to address burned patients in a consistent and systematic manner. B. Scene size-up 1. You should not run into a burning building to save a patient if you are not trained and properly equipped. a. Toxic gases are often present. b. There is the danger of flashover. i. The contents of a room rise in temperature to the point where they all ignite at once. c. The floors, roofs, beams, and walls may collapse. d. Electrical wires, gas lines, and plumbing and heating systems can be unstable. 2. Stage yourself in a place where it is safe to provide patient care. 3. When a recently burned patient comes to you: a. Extinguish the flame and cool the burn. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 10 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns b. Do not permit a person whose clothing is on fire to run because running fans the flames. i. Have the patient stop, drop, and roll. (a) If the patient cannot roll, lower the patient to the ground, cover with a blanket, and pat the fire out. ii. Remove all smoldering clothing. iii. Make sure that any jewelry has been cooled appropriately. iv. If smoldering cloth adheres to the skin, cut it away instead of pulling it off. 4. If possible, determine the mechanism of injury (MOI). a. Consider and examine other mechanisms associated with the burn. i. Did the patient jump from a high window to escape flames? ii. Does the patient have musculoskeletal trauma from tetanic spasms after an electrical burn? iii. Was the patient trapped in an enclosed space? iv. Did the patient lose consciousness? 5. Do not forget to wear appropriate personal protective equipment and follow standard precautions. C. Primary assessment 1. Form a general impression. a. Clues may help identify how serious the injuries are. i. If the patient has a hoarse voice and a chief complaint of “trouble breathing,” the patient may have airway and/or breathing problems. b. More serious burns may present with little or no pain. i. The chief complaint is often “I’m cold.” c. Recently burned patients may appear dazed or disconnected. d. Use compassion when approaching the patient. i. Focusing on the ABCs can help you perform properly. e. Patients with a burn injury may have varied mental status responses. i. Combative patients should be considered hypoxic. ii. Isolated burns do not cause unresponsiveness. (a) Toxic inhalations can. (b) Unresponsive burn patients must be assessed for other deadly injuries. 2. Airway and breathing a. Airway management is a priority in a patient with a burn. b. Signs of airway involvement in a burn patient include: i. Hoarseness ii. Cough iii. Singed nasal or facial hair iv. Facial burns v. Carbon in the sputum vi. History of burn in an enclosed space © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 11 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns c. Laryngeal edema can develop with alarming speed. i. Early endotracheal (ET) intubation could be lifesaving. (a) Should be performed by the most experienced paramedic on your team. d. To intervene early, you need to spot the problem early. i. Listen to lung sounds. ii. Note if signs and symptoms of edema are present. iii. Patients with preexisting lung disease may have bronchospasm after even minor exposure to smoke. (a) May respond to inhaled beta-2 agonists e. Anyone suspected of having a burn to the upper airway may benefit from humidified, cool O2. i. If you do not carry a high-output humidifier, consider using an aerosol nebulizer to administer normal saline. 3. Circulation a. During the first 24 to 48 hours of burn care, fluid resuscitation is emphasized to prevent burn shock. i. Burn shock is a result of hypovolemia caused by fluid shifts that occur after the burn. ii. Large volumes of fluid are not needed during the first minutes of prehospital care. (a) Unless injury occurred some time ago b. Do not delay transport by making multiple attempts at vascular access. i. It is preferable to avoid starting IV lines through burned tissue. ii. Intraosseous access may provide you with more choices. 4. Assess burn severity. a. Evaluate severity to determine which facility the patient should be transported to. b. Approximate the total body surface area (TBSA) burned. i. Most practitioners advocate counting only the areas of partial- and full-thickness burns. c. The universal method of calculating the burned area burned is the rule of nines. i. Divide the body into 9% segments. ii. Add the portions of the body to obtain a total of the body area affected. iii. Different rules apply to infants, children, and adults. d. Another method is the rule of palms (rule of ones). i. Use the size of the patient’s palm to represent 1% of the body surface area. ii. Helpful when the burn covers less than 10% of the body surface area or is irregularly shaped e. The Lund and Browder chart is another method. i. Divide the body into even smaller and more specific regions. f. The American Burn Association has also published burn severity classifications. 5. Transport decision a. You will need to estimate the burn’s size and severity to report to the receiving facility. i. Helpful for determining the appropriate destination and the care to be delivered © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 12 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns b. Patients with the following injuries should be transferred to a burn specialty center (burn unit): i. Partial-thickness burns of more than 10% of the body surface area ii. Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints iii. Full-thickness burns in any age group iv. Electrical burns, including lightning v. Chemical burns vi. Inhalation burns vii. Burn injuries in conjunction with preexisting medical conditions that could: (a) Complicate management (b) Prolong recovery (c) Affect mortality viii. Burns and concomitant trauma in which the burn injury poses the greatest risk of morbidity or mortality ix. Burn injury that requires special social, emotional, or long-term rehabilitation c. Balance the need for accuracy against the time required to make an estimate of the TBSA. D. History taking 1. To the degree possible, get a brief history from the patient. a. Patients with preexisting diseases may be triaged as critical even if the injury is small. b. Allergies, medications, and other medical history may influence the patient’s care. E. Secondary assessment 1. Intended to make sure that no other injuries have higher priority for treatment a. Pay attention to the circumstances of the burn and the possible MOI. 2. Look for injuries to the eyes. a. Cover injured eyes with moist, sterile pads. 3. Check for circumferential burns. a. b. c. d. e. Progressive edema beneath a circumferential burn may act as a tourniquet. If in the neck, it may obstruct the airway. If in the chest, it may restrict respiratory excursion. If in an extremity, it may cut off the circulation and put the extremity in jeopardy. Patients with circumferential burns must reach a medical facility quickly. 4. Check and document distal pulses often. F. Reassessment 1. If the patient has a significant MOI, perform a full-body exam and reassessment en route to the ED. 2. Reassessment of vital signs is done every: a. 5 minutes for critical patients b. 15 minutes for lower priority patients © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 13 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns V. Emergency Medical Care A. Definitive burn care can be divided into four phases: 1. Initial evaluation and resuscitation 2. Initial wound excision and biologic closure 3. Definitive wound closure 4. Rehabilitation, reconstruction, and reintegration B. Burn patient care is measured in weeks, not hours. 1. Burns not only cause physical trauma, they also impose the following types of burdens: a. Emotional b. Psychological c. Financial C. General management 1. You should only turn your attention to the burn itself when the ABCs are under control. a. Have all resuscitative equipment ready for use. 2. Burn patients fall into four categories for airway management. a. The patient with an acutely decompensating airway who requires field intubation i. Includes: (a) Burn patients who are in cardiac or respiratory arrest (b) Responsive patients whose airways are swelling in front of you ii. You need to plan for the possibility that you cannot intubate. (a) Surgical airways or rescue devices may be necessary. b. The patient with a deteriorating airway from burns and toxic inhalations who might require intubation i. Better to defer treatment to hospital teams ii. Attempt to intubate only if the patient’s airway continues to swell and intubation will become impossible if you wait. (a) Try to consult medical control for advice. (b) Explain carefully to the patient what is to be done, why it is necessary, and how he or she can best cooperate. (c) Have all equipment set up at your side. iii. Serious consideration should be made toward performing rapid-sequence intubation. iv. The “most experienced” intubator should perform this procedure. v. Select the largest ET tube that will not cause additional trauma. vi. Edema of the face can actually cause ET tube dislodgment. c. The patient whose airway is currently patent but who has a history consistent with risk factors for eventual airway compromise i. Cool, humidified O2 from a high-output nebulizer is appropriate. (a) You may also use an aerosol nebulizer with saline. ii. Report the patient’s history to hospital personnel. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 14 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns d. The patient with no signs of or risk factors for airway compromise who is in no distress i. Provide supplemental O2 to burn patients even if patients are not in distress due to: (a) Potential for CO poisoning (b) Inaccuracy of pulse oximetry D. Fluid resuscitation 1. Needed for patients with burns covering more than 20% of the body’s total surface area a. If delayed more than 2 hours from the time of the burn, mortality increases. b. Begin to deliver an appropriate amount of fluid as soon as is reasonable. i. An IV line may be inserted in the field to administer fluids and/or pain medications. ii. Try to get a large-bore IV catheter into a large vein, and give lactated Ringer’s solution or normal saline. (a) Do not delay transport to do so. 2. Approximate the amount of fluid needed by using the Consensus formula. a. States that during the first 24 hours, the patient will need: i. 4 mL × body weight (in kg) × percentage of body surface burned (a) Half of that amount needs to be given during the first 8 hours (b) The other half needs to be given over the subsequent 16 hours b. You do not need to deliver the entire initial amount in the field. i. Giving fluid too early or too fast can lead to rapidly increasing peripheral edema. ii. Monitor geriatric and pediatric patients for fluid overload. E. Pain management 1. Assess the patient’s pain before administering analgesia. a. Reassessment should be completed using the same scale every 5 minutes. b. Burn patients may require higher doses than usual to achieve relief. i. Metabolism rates are accelerated. c. Consult protocols or contact medical control for guidance. 2. Pain medication is best given via the IV route. a. Measure and assess the patient’s pain. b. Continuously monitor response to medication. 3. Narcotics remain the drugs of choice. a. Dosing is considerably heavier than normal. i. The pathophysiology of burns may prevent all of the dose from reaching the intended sites. b. Careful response assessment is required for: i. Geriatric and pediatric patients ii. Patients with respiratory compromise c. Titrate multiple doses to the patient’s response. F. Burn shock © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 15 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns 1. Burn shock sets in during a 6- to 8-hour period. a. If an acutely burned patient is in shock in the prehospital phase, look for another injury as the source. 2. Seriously burned patients will not immediately show evidence of burn shock. a. Mortality increases if fluid resuscitation is delayed longer than 2 hours from the time of the burn. b. Helpful to obtain vascular access and begin fluid resuscitation in the field i. Consider: (a) Time from hospital (b) Difficulty of obtaining vascular access (c) Need for analgesia (d) Possibility of additional pathologies that require vascular access G. Thermal burns 1. While assessing burns, consider: a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. Presence or absence of pain Swelling Skin color Capillary refill time Moisture and blisters Appearance of the wound edges Presence of foreign bodies, debris, and contaminants Bleeding Circulatory adequacy 2. Assess for concomitant soft-tissue injury. a. Cool small burn areas and large areas that remain hot. b. Apply dry, sterile, nonadherent dressings. 3. Superficial burns a. Can be very painful, but rarely pose a threat to life b. If patient is reached within the first hour after the injury occurred, immerse the burned area in cool water or apply cold compresses. i. Stops the burning process and relieves pain ii. Do not cool the whole body. (a) A dry sheet or blanket applied over the dressings will help prevent systemic heat loss. c. Do not use salves, ointments, creams, sprays, or any similar materials on the burn. d. Do not apply ice to the burn. e. Transport the patient in a comfortable position to the hospital. 4. Partial-thickness burns a. Treatment in the field is similar to that of superficial burns. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 16 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns b. c. d. e. f. Cool the burned area with water or apply wet or Water-Jel dressings within the first hour. Elevate burned extremities to minimize edema formation. Do not attempt to rupture blisters. Establish IV fluids with lactated Ringer’s solution or normal saline. Administer pain medication as allowed by protocols. 5. Full-thickness burns a. A pain assessment should be completed and pain medication administered. b. Dry dressings are often used. i. Check with your burn center or medical center on their view on wet dressings or analgesia. c. Begin fluid resuscitation preferably within 2 hours of injury. H. Thermal inhalation burns 1. Apply cool mist or aerosol therapy to reduce minor edema. a. Apply an ice pack to the throat if mister is not available. 2. Aggressive airway management may be necessary if the airway is threatened. a. Heat inhalation may produce laryngospasm and bronchospasm in the lower airway. b. Later pulmonary involvement may be from toxic inhalation. VI. Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Specific Burns A. Chemical burns of the skin 1. Occur when the skin comes in contact with strong acids, alkalis or bases, or other corrosives a. The burn progresses as long as the substance remains in contact with the skin. b. Typical management involves removal of the chemical. i. Solutions require copious flushing with water. ii. Powders require brushing off as much as possible before washing. 2. The amount of damage depends on the nature of the chemical, as well as: a. Concentration and quality of the agent i. Agents that are not particularly dangerous may be much more reactive in their concentrated or commercial forms. b. Chemical state or temperature of the agent i. Many gases are transported in their liquid form. (a) Can cause severe burns because they are so cold c. Length of exposure d. Depth of penetration 3. Typically react with the skin and tissues quickly a. In some cases, the injury may take time to develop. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 17 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns 4. Acid burns a. Relatively easy to neutralize b. Acids cause destruction and coagulation of tissues. i. Results in a coagulative necrosis that may actually limit the depth of the burn 5. Alkali burns a. More difficult to neutralize b. Effects are particularly pronounced in burns of the eye. 6. Assessment a. Begin by ensuring your own safety. b. Follow with decontamination of the patient. i. Consider wearing additional protective materials. 7. Management a. b. c. d. Speed is essential. Begin flushing the exposed area with copious amounts of water. Rapidly remove the patient’s clothing. Have the patient bend over when washing the head to avoid chemicals running over the rest of the body. e. Wash the skin folds at joints and between fingers and toes. f. Once washing is complete, wash the body again. i. A mild detergent may aid chemical removal. ii. Flushing is preferable for 30 minutes before moving the patient. (a) For burns caused by strong alkalis, 1 to 2 hours is recommended. g. After flushing, keep the patient covered and warm. h. Several types of chemical burns require special management techniques: i. Dry lime (a) Combination with water will produce a highly corrosive substance (b) Remove the patient’s clothing, and brush as much lime as you can from the skin (wear gloves). (c) Flush copiously with a garden hose or shower. (1) Try to completely overwhelm any chemical reaction with a deluge of water. ii. Sodium metals (a) Produce considerable heat when mixed with water; may explode (b) Cover burn with oil, which will stop the reaction. iii. Hydrofluoric (HF) acid (a) Burns that exceed 3% to 5% of the TBSA can be fatal. (b) Pain will not improve even with continuous flushing. (c) Calcium chloride (CaCl) jelly may be available to help reduce pain and injury. (1) An ampule of CaCl can be mixed with a water-based lubricant to make CaCl jelly in an emergency. iv. Gasoline or diesel fuel © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 18 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns (a) (b) v. Hot tar (a) (b) (c) Prolonged contact may produce a chemical injury to the skin. More effectively removed with a soap solution than water alone. Burns are thermal burns, not chemical burns. Immerse the area in cold water. Once the tar has cooled, there is no need to try to remove it in the field. B. Inhalation burns from other toxic chemicals 1. The solubility properties of the gas will often determine where it affects the airway. a. Highly water-soluble gases will react with mucous membranes of the upper airway. i. Cause immediate irritation and swelling b. Slightly water-soluble gases will react with tissue over time. i. Causes pulmonary edema long after the exposure took place c. Moderately water-soluble gases will depend on the concentration breathed. 2. HF acid is a special case. a. Aggressively binds with calcium ions b. May require the administration of IV calcium c. Significant inhalation often results in death. 3. Assessment a. Have a high index of suspicion for irritant gas exposure if the patient was involved in a: i. Fire ii. Explosion iii. Contaminated environment situation b. Irritant gases will usually cause burning of the eyes. c. Signs of upper airway swelling may signal acute upper airway obstruction. i. Stridor d. Signs of lower airway involvement i. Wheezing and desaturation ii. Pulmonary edema, ranging from crackles to pink froth 4. Management a. Maintain an acceptable O2 saturation level. b. Monitor for signs of continued airway compromise. c. Aerosolized beta-agonists are usually helpful. C. Chemical burns of the eye 1. Chemicals known to cause burns to the eyes include: a. b. c. d. Acids Alkalis Dry chemicals Phenols © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 19 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns 2. Assessment and management a. Flush eyes with copious amounts of water. i. Consider supporting the patient’s head under a faucet or at an eyewash station. b. If the patient wears contact lenses, pause after a minute or two to allow the patient to remove the contact lenses. c. Irrigate well underneath the eyelids. d. Patch the eyes with lightly applied dressings. and begin transport. e. The Morgan lens may make eye irrigation more comfortable and effective. i. Plastic contact lens with IV tubing attached to it ii. Allows IV fluids to flow directly over the surface of the eye (a) Ocular anesthetic drops are preferable. iii. Keep fluid running during insertion and removal. (a) Suction can occur between the lens and the eye if the fluid flow is stopped. f. After flushing, the pH of the eye can be tested with hydrazine paper (pH paper). i. Typically done at the hospital D. Electrical burns and associated injuries 1. Four percent of burn center admissions are from electrical burns. a. Children are involved in the majority of electrocutions in the home. b. Electrical burns may produce devastating internal injuries with little external evidence. 2. May result in two injury sites: a. One at the point where electricity entered the body (entrance wound) b. One where electricity exited the body (exit wound) 3. Degree of tissue injury is related to: a. Resistance of the body tissues i. Wet, thin, clean skin offers less resistance than dry, thick, dirty skin. b. Intensity of current that passes through the victim c. Duration of exposure 4. As electric current travels into the body, it is converted to heat, which follows the current flow. a. The greater the current flow, the greater the heat. i. When the voltage is low, current follows the path of least resistance. ii. When the voltage is high, current takes the shortest path. iii. Alternating current is more dangerous because it can cause repetitive muscle contractions. (a) May “freeze” the victim to the conductor until the current source is turned off. 5. The direction of current flow is also significant. a. Current moving from one hand to the other is particularly dangerous because current may then flow across the heart. 6. Electricity can cause three types of burns: © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 20 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns a. True electrical injury i. Most common type of electrical burn ii. May see a bull’s-eye lesion at these sites, with: (a) Central, charred zone of full-thickness burns (b) Middle zone of cold, gray, dry tissue (c) Outer, red zone of coagulation necrosis b. Arc-type or flash burn i. Electrothermal injury caused by the arcing of electric current ii. Arc has a temperature from 3,000°C to 20,000°C. (a) High enough to produce significant charring c. Flame burn i. Occurs when electricity ignites a person’s clothing or surroundings. 7. Electrical burns have a strong possibility of severe internal injury. a. Burns may be only one of the problems experienced by a patient who has come in contact with an electrical source. b. Two most common causes of death from electrical injury are asphyxia and cardiac arrest. i. Asphyxia may occur when: (a) Prolonged contact with alternating current induces contractions of the respiratory muscle. (b) Current passing through the respiratory center in the brain knocks out the impulse to breathe. ii. Currents as small as 0.1 amp can trigger ventricular fibrillation if they pass through the heart. c. Electricity can disrupt the nervous system. i. Complications may include: (a) Peripheral nerve deficit (b) Seizures (c) Delirium (d) Confusion (e) Coma (f) Temporary quadriplegia ii. May affect muscle coordination and strength iii. May cause cataracts if it contacts the eye iv. Severe muscle spasms may lead to fractures and dislocations. 8. Never let obvious injuries distract you from a complete assessment. 9. Assessment a. The first priority is to protect yourself and bystanders. i. Do not use an object to try to dislodge the patient from the current source. ii. Do not try to cut the wire. iii. Do not go anywhere near a high-tension line. iv. A downed wire that “looks dead” can jump back to life. v. Call the electric company and wait until a qualified person can shut off the power. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 21 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns b. c. d. e. f. g. Once the electric hazard has been neutralized, assess the patient. Start CPR, and attach the monitor to identify ventricular fibrillation. Open the airway using the jaw-thrust maneuver. Cardiac monitoring is indicated for 24 hours after the injury. Make careful note of the patient’s state of consciousness, and record vital signs. Try to determine the path the current has taken through the body. i. A rigid abdomen or extremity may indicate a serious internal injury. 10. Management a. Prioritize patient care. i. If injuries are life-threatening, begin related care, and prepare to transport the patient. b. Administer early O2 therapy. c. Manage the patient for impending shock. d. Make transport decisions early, considering the regional resources. i. Contact medical control for advice. e. Talk with patients, and explain what you are doing. E. Lightning-related injuries 1. Lightning strikes when a massive discharge of electricity occurs between two bodies that have different charges. a. Example, between a thundercloud and the ground b. If any object projects above the surface of the earth that is a better conductor of electricity than the air, that object will “attract” the lightning bolt. c. A person need not sustain a direct hit from lightning to be injured; in fact, most victims are not struck directly. i. The victim may be splashed by lightning striking a nearby tree or other projecting object. (a) Results in an arc-type or flash burn that leaves a “feathering” pattern on the skin. ii. Ground current produced by lightning striking the ground can also cause severe injury. 2. The best treatment for lightning injuries is prevention. a. Don’t be the tallest object that is a good conductor. i. Stay away from the middle of large, open areas. ii. If you are stuck in the middle of an open area, try to be as small as you can. b. Don’t stand under or near the tallest object that is a good conductor. c. Take shelter in the most substantial structure that you can. i. A large building with a lightning suppression system is the best choice. ii. An enclosed building is better than an open one. d. Avoid touching good conductors during a lightning storm, including: i. Plumbing fixtures ii. Fences iii. Electrical appliances, particularly those connected to wires outside 3. Lightning carries enormous electrical power. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 22 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns a. Its energy can reach 100 million volts. b. Peak currents can be in the range of 200,000 amps. c. It is direct current, and the duration of exposure is milliseconds. i. Lightning injuries tend to resemble blast injuries (a) Damages to the tympanic membranes of the ears and air-containing internal organs (b) Muscle damage may occur (c) A massive direct-current countershock depolarizes the heart 4. Continued ventilatory support may be required. a. The immediate threats to life are airway obstruction, respiratory arrest, and cardiac arrest. 5. Assessment a. Two special considerations: i. If the electrical storm is still going on, get any patients and rescuers to a safe place. (a) Lightning can strike twice in the same place. (b) There is no hazard in touching the victim. ii. A lightning strike is apt to injure more than one person. (a) Upon arrival at the scene, perform a rapid size-up to determine the number of patients. b. Start CPR when necessary. i. Patients with cardiac arrest caused by a lightning strike deserve aggressive, continuing CPR. 6. Management a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. Make sure the scene is safe. Priority goes to patients who are not breathing. Perform CPR as needed. Administer supplemental oxygen. Monitor cardiac rhythm. Insert a large-bore IV catheter, and run in normal saline solution wide open. Cover surface burns with dry, sterile dressings. Splint fractures. If the patient has fallen, immobilize the cervical spine. F. Radiation burns 1. Suspect radiation and attempt to determine whether ongoing exposure exists. a. Special response units may be equipped with radiation detectors. 2. Three types of ionizing radiation: a. Alpha i. Particles have little penetrating energy and are easily stopped by the skin. b. Beta i. Particles have greater penetrating power and can travel much farther in air. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 23 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns ii. Can be blocked by simple protective clothing. c. Gamma i. Very penetrating and easily passes through the body and solid materials. 3. Radiation is measured in units of: a. Radiation equivalent in man (rem), or b. Radiation absorbed dose (rad) i. 100 rad = 1 gray (Gy) (a) Small amounts of everyday background radiation are measured in rad. (b) The amount released in a major incident may be measured in Gy. (1) Mild radiation sickness expected with 1 to 2 Gy (100 to 200 rad). (2) Moderate sickness expected with 2 to 5 Gy. (3) Severe sickness expected with 4 to 6 Gy. (4) Fatality expected with more than 8 Gy. 4. In some types of incidents patients may be contaminated with radioactive matter. 5. Acute radiation syndrome a. Causes hematologic, central nervous system, and gastrointestinal changes i. Changes may occur over time and will not be apparent during contact with EMS providers. ii. Unresponsive patients who vomit within 10 minutes of exposure will not survive. iii. Those who vomit in less than an hour have severe exposure and a 30% to 80% survival rate. iv. Those with moderate exposure will vomit within 1 to 2 hours and have a 95% to 100% survival rate. 6. Radiation contact burns a. A person who handles a radioactive source briefly may sustain a local soft-tissue injury. i. Injury could resemble anything from superficial sunburn to a chemical burn. b. Burns could appear hours or days after exposure. 7. Assessment a. b. c. d. Determine if the scene is safe to enter. Determine what protective gear you will need. It may be appropriate to contact the hazardous materials response team. Once the scene is deemed safe, proceed with your primary assessment. i. Assess mental status and ABCs. ii. Prioritize the patient’s care. e. When confronted with large numbers of patients who have been exposed to radiation and received burns, keep the 30% rule in mind when triaging. 8. Management a. Decontaminate patients before transport. b. Gently irrigate open wounds. c. Notify the ED as soon as possible. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 24 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns d. With contact radiation burns, decontaminate the wound as if it were a chemical burn before treating. e. Antidotal therapy should be considered only under the guidance of a knowledgeable physician or public health agency. f. Limit your duration of exposure. g. Increase your distance from the source. h. Attempt to place shielding between yourself and sources of gamma radiation. VII. Management of Burns in Pediatric Patients A. Escaping from a fire can be difficult for children. 1. They are not as effectively awakened by smoke detectors. 2. They are often disoriented after waking. B. Young children are also more likely to sustain severe scald injuries. 1. Their skin is thin and respiratory structures are delicate. C. In children, fluid resuscitation may be more challenging. 1. They may require more fluid per kilogram than adults because of their increased body surface/weight ratio. 2. They may require dextrose-containing solutions earlier than adults because of poor glycogen stores. a. Blood glucose monitoring should be routinely performed. VIII. Management of Burns in Geriatric Patients A. Approximately 1,200 older adults die of fire-related causes each year. 1. Burns from fires caused by smoking while wearing supplementary O2 2. Cooking fires B. Elderly patients are particularly sensitive to respiratory injuries. C. Geriatric patients may have poor glycogen stores. 1. Blood glucose levels should be checked to assess for hypoglycemia. 2. Cardiac monitoring should be implemented. 3. Pulmonary edema is more likely to develop. IX. Long-Term Consequences of Burns A. The patient 1. People with major injuries average about 1 day of inpatient treatment for each 1% of the TBSA burned. 2. Survivors are left with long-term consequences, including problems with: a. Thermoregulation © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 25 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns b. Motor function c. Sensory function B. The provider 1. Caring for patients with severe burn emergencies can be horrifying. a. b. c. d. Scenes are chaotic and dangerous. Patients are in severe pain. Burned hair and flesh can be smelled. Sheets of tissue may peel off the patient. 2. With proper training, confidence, and courage, you can make a large impact in the treatment and survival of patients. X. Summary A. Although you probably will not see moderate or severe burns on a daily basis, you will encounter some serious burn injuries during your career. B. The skin has four functions: to protect the underlying tissue from injury and exposure, to regulate temperature, to prevent excessive loss of water from the body, and to act as a sense organ. C. Burns are diffuse soft-tissue injuries created from destructive energy transferred via thermal, electrical, or radiation energy. D. Significant burn damage to the skin may make the body vulnerable to bacterial invasion, temperature instability, and major disturbances of fluid balance resulting in burn shock. E. Thermal burns include flame, scald, contact, steam, and flash burns. F. Burns can affect the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematological, and endocrine systems. The most important systemic response to significant burn trauma is burn shock. G. When burn shock occurs, the contents of the capillaries leak out of the circulation and into the interstitial spaces. Cells take in increased amounts of salt and water from the fluid around them. The body’s ability to distribute oxygen and glucose is hampered. Adequate fluid resuscitation is needed. H. Burn wounds of the skin may be superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness. I. A superficial burn involves only the epidermis, and skin appears red and swollen. J. A partial-thickness burn involves the epidermis and part of the dermis. Moderate partial-thickness burns usually are blistered, red, and extremely painful. Deep partialthickness burns damage the hair follicle and sweat and sebaceous glands. K. A full-thickness burn involves destruction of the epidermis, the dermis, and the basement membrane of the dermis. After this type of burn, skin will not regenerate. Such a burn may appear white and waxy, brown and leathery, or charred. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 26 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns L. Inhalation burns may cause rapid airway compromise via heat and/or toxic chemicals entering the airway and lungs. Signs of irritation include coughing, wheezing, and possible stridor, signifying airway swelling. M. Establishing scene safety should be your first priority in responding to a burn call. Significant threats are likely to remain at the scene of a fire, chemical spill, electrical burn incident, lightning strike, or radiation leak. N. The many types of burns, coupled with the many possible presentations, can challenge your assessment skills. Address a burned patient in a consistent, efficient, and systematic manner so you do not develop tunnel vision and miss other occult injuries. O. Once ABCs are addressed, assess the total body surface area (TBSA) burned, using the rule of palms, rule of nines, or the Lund and Browder chart. This is an important step because burn severity relates to the need for transport to a burn unit. Remember that when using the rule of nines, different rules apply for infants, children, and the elderly. P. Three cornerstones of the emergency medical care of burns are airway management, fluid resuscitation, and pain management. Cooling and sterile bandaging are indicated for certain thermal burns. Chemical burns generally require copious flushing with water, with certain exceptions. Q. Many burn patients will ultimately require intubation, even if during their initial presentation they were able to talk to you. Patients who are in cardiac or respiratory arrest, or whose airways are rapidly swelling, will need field intubation. A deteriorating airway may or may not require field intubation. A patient whose airway is currently patent but who has a history consistent with risk factors for airway compromise may or may not need field intubation. R. Patients with more than 20% body surface area burns will need fluid resuscitation. It is important to give the correct amount of fluid. If fluid resuscitation is delayed more than 2 hours from the time of the burn in severely burned patients, resuscitation is complicated. Deliver an appropriate amount of fluid to the burn patient as soon as is reasonable. S. The Consensus formula is an equation used to determine the amount of fluid a burned patient will need during the first 24 hours. Half of the amount must be given during the first 8 hours. The remainder is given over the remaining 16 hours. T. Remember to assess the patient’s pain and provide aggressive pain management. Pain medication is best given intravenously. Burn patients may require higher than usual doses of pain medications to achieve relief. Reassess the patient’s pain every 5 minutes. U. Chemical burns may affect the skin, eyes, or airway. Typical management for removal of chemical solutions from the skin is copious flushing with water; management of powders requires brushing off as much of the substance as possible before washing. Management of chemicals from the eye involves flushing the eyes with copious amounts of water and possibly removing contact lenses. Consider use of a Morgan lens. V. In cases of electrical burn, electric current is converted to heat as it travels through the body, causing extensive damage. Electrical burns generally leave two wounds, an entrance wound and a much larger exit wound. Assessment of electrical injuries includes scene © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 27 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns safety considerations and the start of CPR if indicated. Management includes treating lifethreatening injuries and shock. W. Most radiation burns are caused by gamma radiation or x-rays. Assessment includes scene safety concerns. Management involves decontamination, irrigation, washing, possibly antidote administration, and transport. X. Pediatric patients can be more easily harmed by thermal injuries than other patients, and fluid resuscitation may be more challenging. Children may require dextrosecontaining solutions earlier than adults; perform blood glucose monitoring routinely in seriously ill children. Y. Elderly patients are also particularly sensitive to respiratory insults. They may have poor glycogen stores; check their blood glucose levels for hypoglycemia. Perform cardiac monitoring. Watch for pulmonary edema if performing fluid resuscitation. Post-Lecture This section contains various student-centered end-of-chapter activities designed as enhancements to the instructor’s presentation. As time permits, these activities may be presented in class. They are also designed to be used as homework activities. Assessment in Action This activity is designed to assist the student in gaining a further understanding of issues surrounding the provision of prehospital care. The activity incorporates both critical thinking and application of paramedic knowledge. Instructor Directions 1. Direct students to read the “Assessment in Action” scenario located in the Prep Kit at the end of Chapter 32. 2. Direct students to read and individually answer the quiz questions at the end of the scenario. Allow approximately 10 minutes for this part of the activity. Facilitate a class review and dialogue of the answers, allowing students to correct responses as may be needed. Use the quiz question answers noted below to assist in building this review. Allow approximately 10 minutes for this part of the activity. 3. You may wish to ask students to complete the activity on their own and turn in their answers on a separate piece of paper. Answers to Assessment in Action Questions 1. Answer: D. keeping the patient flat and flushing his eyes for 30 minutes before transport and while en route. Rationale: With a pH of 13, this substance is extremely alkaline and irreversible eye damage occurs quickly. Flushing the eyes with copious amounts of water or normal saline for 30 minutes is necessary and may continue to be necessary once in the emergency department. One technique that can work well while en route to the hospital is to set up 1 or 2 liter bags of normal saline with a macro drip administration set attached. If both eyes require flushing, consider attaching additional tubing as a ‘piggyback’ so that constant irrigation of both eyes can occur. It may be necessary to alternate eyes to avoid cross-contamination. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 28 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns 2. Answer: B. The presence of contact lenses Rationale: Contact lenses need to be removed right away. Chemicals can stay trapped behind the lens and continue to burn even after copious irrigation. 3. Answer: C. use them to help the patient keep his eyes open. Rationale: Use the eye drops (ie, tetracaine) to numb the eyes, which will make it easier for the patient to tolerate the irrigation and keep his eyes open. 4. Answer: A. minutes. remove them from the skin while wearing gloves and flush the skin for 30 Rationale: Remove the concrete specks, but be sure your skin is protected. Any concrete on the body needs to be removed and the area irrigated for 30 or more minutes to avoid tissue damage. It is particularly important to clean the area around the eyes so that dried concrete doesn’t wash back into the eyes. 5. Answer: A. visual acuity and any vision changes. Rationale: Visual acuity and vision changes are important to monitor before, during, and after eye irrigation but should be done beforehand only if treatment is not delayed. Redness is not a good indicator of any remaining foreign bodies as the redness from the initial irritation and chemical exposure can last for several hours after the chemical is removed. 6. Answer: A. sweep the ambulance and wipe away any debris. Rationale: Sweep the ambulance and wipe away any debris, making sure that proper personal protective equipment is used. Use a particulate respirator to avoid inhaling concrete dust. Use gloves to wipe surfaces clean of any concrete debris. Additional Questions 7. Rationale: Find the person in charge of safety on the job site. This may be the foreman, the superintendent, the labor union representative, or it may be someone from a private safety provider. The people working on the scene should have access to the material safety data sheet for that particular chemical. The workers often know what precautions need to be taken to avoid harm from these chemicals. You need to ask since they may assume that you already know. At the very least, get the name of the product(s) being used. 8. Rationale: One of the most significant similarities is that both can cause extensive internal and often invisible damage to the body. The extent of the damage, which can include tissue necrosis, nerve damage, and other internal injuries, may not become apparent for several days. Assignments A. Review all materials from this lesson and be prepared for a lesson quiz to be administered (date to be determined by instructor). B. Read Chapter 33, Face and Neck Trauma, for the next class session. © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 29 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns Unit Assessment Keyed for Instructors 1. Describe burn shock. Answer: Burn shock occurs because of two types of injury: fluid loss across damaged skin and a series of volume shifts within the rest of the body. Capillaries become leaky, so intravascular volume oozes out of the circulation and into the interstitial spaces. The cells of normal tissues then take in increased amounts of salt and water from the fluid around them. As blood pressure falls, the body responds with tachycardia and vasoconstriction, which limits blood flow further and continues the shock cycle. A variety of chemical mediators are released that may cause additional damage and worsen the chain of events. Depending upon the nature of the burn, coagulation disorders may cause the patient’s blood to clot more easily, resulting in emboli, or fail to clot, causing excessive bleeding. (p 1578) 2. Provide general examples of how thermal burns occur. Answer: Thermal burns can occur when skin is exposed to temperatures higher than 111°F (44°C), or when the heat absorbed exceeds the tissue’s capacity to dissipate it. In general, the severity of a thermal injury correlates directly with temperature, concentration, or amount of heat energy possessed by the object or substance, and the duration of exposure. (p 1578) 3. What are the three pathologic progressions of burns? Answer: A burn wound is categorized by the degree of injury. Historically, such an injury has been described by three pathologic progressions or zones, which radiate from the central zone of greatest damage. Skin nearest the heat source suffers the most profound cellular changes. The central area of the skin, which suffers the most damage, is called the zone of coagulation. There is little or no blood flow to the injured tissue in this area. The peripheral area surrounding the zone of coagulation has decreased blood flow and inflammation; it is known as the zone of stasis. This area may undergo necrosis within 24 to 48 hours after the injury, particularly if perfusion is compromised by burn shock. Last, the zone of hyperemia is the area least affected by the thermal injury. In this area, cells will typically recover in 7 to 10 days. Similar to a myocardial infarction or stroke, the role of treatment is to salvage as much of the injured tissue as possible by improving perfusion and limiting the secondary changes that turn damaged tissue into dead tissue. (p 1579) 4. What are the degrees of burn depth? Answer: Burn depth is also categorized by severity—first, second, and third degree. Additional categories exist, such as fourth, fifth, and sixth-degree burns, for describing deeper destruction into tissue, muscle, and bone. Although these categorizations are still used by burn centers, paramedics should limit their assessment to superficial, partial-thickness, and full-thickness burns to simplify the process and avoid confusion and miscommunication. (p 1579) 5. Describe a superficial burn. Answer: A superficial burn involves the epidermis only. The skin is red and swollen and, when touched, the color will blanch and return. Usually blisters are not present. Patients will experience © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 30 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns pain because nerve endings are exposed to the air. Superficial burns will heal spontaneously in 3 to 7 days. The most common example is a sunburn. (p 1579) 6. Describe a partial thickness burn. Answer: A partial-thickness burn involves the epidermis and varying degrees of the dermis. In general, the deeper the partial-thickness burn, the more painful it is. The sensation of deep pressure remains intact. This burn category can be subdivided into moderate partial-thickness and deep partial-thickness burns. With a moderate partial-thickness burn, the skin is red; when touched, the color will blanch and return. Usually there are blisters or moisture present, and the patient may experience extreme pain. Hair follicles remain intact. A moderate partial-thickness burn will typically heal spontaneously but may scar or have a changed appearance. In contrast, a deep partial-thickness burn extends into the dermis, damaging the hair follicle and sweat and sebaceous glands. Hot liquids, steam, or grease are often to blame for these injuries. The color of the burn may be deceptive, and the delineation between deep partial thickness and full thickness may be difficult to determine in the field. (p 1580) 7. Describe a full-thickness burn. Answer: A full-thickness burn involves destruction of both layers of the skin, including the basement membrane of dermis that produces new skin cells; therefore, the skin is incapable of self-regeneration. In such an injury, the skin may appear white and waxy, brown and leathery, or charred. Leathery skin is called eschar, and is dry and hard. No capillary refill occurs with this type of burn because the capillaries have been destroyed. Sensory nerves are destroyed as well, so there may be no pain in the full-thickness section. Because patients usually have mixed depths of burns, they will often experience significant pain in the areas surrounding the full-thickness burns. Treatment of a full-thickness burn will often require skin grafting because the dermis has been destroyed (p 1580) 8. What are the four phases of definitive burn care? Answer: Definitive burn care can be divided into four phases: initial evaluation and resuscitation, initial wound excision and biologic closure, definitive wound closure, and rehabilitation, reconstruction, and reintegration. Although paramedics will be most heavily involved in the first phase, it is important to appreciate the magnitude of care that a patient with a severe, or even moderate, burn must receive. Early actions of the paramedic may dramatically affect the patient’s long-term outcome. Paramedics may also find themselves transporting patients to specialty or rehabilitation facilities at later stages of their care. (pp 1586-1587) 9. What is the Consensus formula? Answer: The Consensus formula approximates the amount of fluid the burned patient will need for resuscitation. The formula states that during the first 24 hours, the burned patient will need the following: 4 mL × body weight (in kg) × percentage of body surface burned. Half of that amount needs to be given during the first 8 hours, and the other half needs to be given over the subsequent 16 hours. (p 1588) © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 31 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns 10. What factors determine the amount of damage that occurs from a chemical burn? Answer: The amount of damage from a chemical burn depends on the nature of the chemical involved, as well as: The concentration and quality of the agent The chemical state or temperature of the agent The length of exposure The depth of penetration (p 1591) © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 32 Nancy Caroline’s Emergency Care in the Streets, Seventh Edition Chapter 32: Burns Unit Assessment 1. Describe burn shock. 2. Provide general examples of how thermal burns occur. 3. What are the three pathologic progressions of burns? 4. What are the degrees of burn depth? 5. Describe a superficial burn. 6. Describe a partial thickness burn. 7. Describe a full-thickness burn. 8. What are the four phases of definitive burn care? 9. What is the Consensus formula? 10. What factors determine the amount of damage that occurs from a chemical burn? © 2013 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company • www.jblearning.com 33