Drillers propose deep-Earth quest By Jonathan Amos Science

advertisement

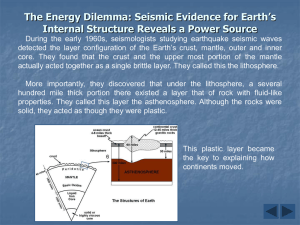

Drillers propose deep-Earth quest By Jonathan Amos Science correspondent, BBC News This spring, scientists will try to retrieve the deepest types of rock ever extracted from beneath the seabed. The drilling project is taking place off Costa Rica, and will attempt to reach some 2km under the ocean floor. Writing in the journal Nature, the scientists say their ultimate goal is to return even deeper samples - from the mantle layer below the crust. Obtaining these rocks would provide a geological treasure trove "comparable to the Apollo lunar rocks". One of the scientists, Damon Teagle from the University of Southampton, UK, told BBC News: "There are some fundamental questions about the way that the Earth has evolved over its history that we will only be able to answer once we completely understand the structure of the crust overlaying the mantle, the interface between the mantle and the crust (known as the Mohorovicic Discontinuity, or Moho), and then also the nature of the mantle itself." The mantle makes up the bulk of our planet's volume and mass. It stretches from the bottom of the crust down to the Earth's iron-nickel core some 2,900km further down. Its rocks are distinct in composition from those that make up the continents and the ocean floor. They are thought predominantly to be peridotites, which comprise magnesium-rich, silicon-poor minerals such as olivine and pyroxene. The properties of these rocks and the conditions to which they are subjected mean much of the mantle is in motion. Slow convection in this dominant layer plays a key role in the tectonic processes that help shape the surface above. Scientists already have a range of samples from deep inside the Earth. Some of these were lifted up in the processes that built Earth's mountain ranges, and others have come up in the lavas of volcanoes. But all the samples are altered in some way by the means that brought them to the surface, and scientists would dearly love to see pristine specimens. The last attempt to drill into the mantle, Project Mohole, was conducted in 1961. It failed, but its drill location could be the site of a new effort. Two other potential sites are being assessed, including one being actively investigated this spring. "We need to know the exact chemical composition, and this composition varies from place to place," said Benoit Ildefonse from the Montpellier University 2, France. "It's important because, depending on the composition, the physical properties of the mantle will also vary and eventually will have some effect on the dynamics of the Earth - on the way this mantle is able to move, on the way it's able to eventually partially melt and produce some magma that is carried out to the surface, creating the new ocean crust." Drilling into the mantle on land is impractical because the continents are where the crust is thickest - some 30-60km thick. Going through the younger, thinner crust of the ocean floor has the advantage that scientists need only drill to about 6km of depth - but this option has the particular difficulty of setting up and operating a rig at sea. Researchers will test the necessary techniques in the next few years, and assess three potential Pacific Ocean sites. Already they have a ship capable of hosting the project. This is the giant Japanese Chikyu vessel, which is capable of carrying 10km of drilling pipes. It will, though, need a host of new technologies, such as new types of drill bit to make coring into the mantle manageable. "This would be a very significant engineering undertaking," explained Dr Teagle. "We're talking 6km of ocean crust and we'd want to get some distance into the mantle - maybe 500m. So that's a very deep hole; and it would be in water that is perhaps 34km deep as well. Also, we would encounter temperatures around 250-300 degrees at least. It would be hot and demanding." Researchers do not expect to have the necessary technology and funding in place to begin drilling into the mantle much before about 2018. This spring's expedition will re-open a previously drilled hole called 1256D. It will allow scientists to recover for the first time gabbros from the lower crust. These samples will be the deepest rocks of their type ever extracted from beneath the sea floor. Dr Ildefonse told BBC News: "The hole currently is residing at the very transition of the upper-part of the crust, which is basically the basalts you see erupted at the sea floor, and the lower-part of the crust which has rocks of the same composition but that cool much slower and are called gabbros. "We want, for the first time ever, to sample these kinds of rocks in situ, to test the different models that we have to explain the behaviour of this crust. To do this we need to go about 400m deeper into the crust." The deepest hole ever drilled on land was sunk by a Russian project and went down just over 12km down.